Bantu refugee children from Somalia at a farewell party in Florida before being relocated to other places in the United States.

Nearly half of all refugees are children, and almost one in three children living outside their country of birth is a refugee. These numbers encompass children whose refugee status has been formally confirmed, as well as children in refugee-like situations.

In addition to facing the direct threat of violence resulting

from conflict, forcibly displaced children also face various health

risks, including: disease outbreaks and long-term psychological trauma, inadequate access to water and sanitation, nutritious food, and regular vaccination schedules.

Refugee children, particularly those without documentation and those who travel alone, are also vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Although many communities around the world have welcomed them, forcibly displaced children and their families often face discrimination, poverty, and social marginalization in their home, transit, and destination countries.

Language barriers and legal barriers in transit and destination

countries often bar refugee children and their families from accessing

education, healthcare, social protection, and other services. Many

countries of destination also lack intercultural supports and policies

for social integration. Such threats to safety and well-being are amplified for refugee children with disabilities.

This woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld, 1860 depicts Jesus as a refugee child fleeing the Massacre of the Innocents.

Legal protection

The Convention on the Rights of the Child,

the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, includes four

articles that are particularly relevant to children involved in or

affected by forced displacement:

- the principle of non-discrimination (Article 2)

- best interests of the child (Article 3)

- right to life and survival and development (Article 6)

- the right to child participation (Article 12)

States Parties to the Convention are obliged to uphold the above articles, regardless of a child's migration status. As of November 2005, a total of 192 countries have become States Parties to the Convention. Somalia and the United States are the only two countries that have not ratified it.

The United Nations 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees

is a comprehensive and rigid legal code regarding the rights of

refugees at an international level and it also defines under which

conditions a person should be considered as a refugee and thus be given

these rights.

The Convention provides protection to forcibly displaced persons who

have experienced persecution or torture in their home countries.

For countries that have ratified it, the Convention often serves as the

primary basis for refugee status determination, but some countries also

utilize other refugee definitions, thus, have granted refugee status

not based exclusively on persecution. For instance, the African Union

has agreed on a definition at the 1969 Refugee Convention,

that also accommodates people affected by external aggression,

occupation, foreign domination, and events seriously disturbing public

order. South Africa has granted refugee status to Mozambicans and Zimbabweans

following the collapse of their home countries’ economies.

Other international legal tools for the protection refugee children include two of the Protocols supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime which reference child migration:

- the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children;

- the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea, and Air.

Additionally the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

covers the rights of the children of migrant workers in both regular

and irregular situations during the entire migration process.

Stages of the refugee experience

Refugee

experiences can be categorized into three stages of migration: home

country experiences (pre-migration), transit experiences

(transmigration), and host country experiences (post-migration).

However, the large majority of refugees do not travel into new host

countries, but remain in the transmigration stage, living in refugee

camps or urban centres waiting to be able to return home.

Home country experiences (pre-migration)

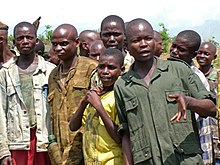

Former child soldiers in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The pre-migration stage refers to home country experiences leading up

to and including the decision to flee. Pre-migration experiences

include the challenges and threats children face that drive them to seek

refuge in another country.

Refugee children migrate, either with their families or unaccompanied,

due to fear of persecution on the premise of membership of a particular

social group, or due to the threat of forced marriage, forced labor, or conscription into armed forces.

Others may leave to escape famine or in order to ensure the safety and

security of themselves and their families from the destruction of war or

internal conflict.

A 2016 report by UNICEF found that, by the end of 2015, five years of open conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic

had forced 4.9 million Syrians out of the country, half of which were

children. The same report found that, by the end of 2015, more than ten

years of armed conflict in Afghanistan had forced 2.7 million Afghans

beyond the country's borders; half of the refugees from Afghanistan were

children. During times of war, in addition to being exposed to violence, many children are abducted and forced to become soldiers. According to an estimate, 12,000 refugee children have been recruited into armed groups within South Sudan. War itself often becomes a part of the child's identity, making reintegration difficult once he or she is removed from the unstable environment.

Examples of children's pre-migration experiences:

- Some Sudanese refugee children reported that they had either experienced personally or witnessed potentially traumatic events prior to departure from their home country, during attacks by the Sudanese military in Darfur. These events include instances of sexual violence, as well as of individuals being beaten, shot, bound, stabbed, strangled, drowned, and kidnapped.

- Some Burmese refugee children in Australia were found to have undergone severe pre-migration traumas, including the lack of food, water, and shelter, forced separation from family members, murder of family or friends, kidnappings, sexual abuse, and torture.

- In 2014 the President of Honduras testified in front of the United States Congress that more than three-quarters of unaccompanied child migrants from Honduras came from the country's most violent cities. In fact, 58 percent of 404 unaccompanied and separated children interviewed by the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, about their journey to the United States indicated that they had been forcibly displaced from their homes because they had either been harmed or were under threat of harm.

In general, children may also cross borders for economic reasons,

such as to escape poverty and social deprivation, or some children may

do so to join other family members already settled in another State. But

it is the involuntary nature of refugees' departure that distinguishes

them from other migrant groups who have not undergone forced

displacement. Refugees,

and even more so their children, are neither psychologically nor

pragmatically prepared for the rapid movement and transition resulting

from events outside their control. Any direct or witnessed forms of violence and sexual abuse may characterize refugee children's pre-migration experiences.

Transit experiences (transmigration)

The

transmigration period is characterized by the physical relocation of

refugees. This process includes the journey between home countries and

host countries and often involves time spent in a refugee camp. Children may experience arrest, detention, sexual assault, and torture during their translocation to the host country.

Children, particularly those who travel on their own or become

separated from their families, are likely to face various forms of

violence and exploitation throughout the transmigration period.

The experience of traveling from one country to another is much more

difficult for women and children, because they are more vulnerable to

assaults and exploitation by people they encounter at the border and in

refugee camps.

Trafficking

Smuggling,

in which a smuggler illegally moves a migrant into another country, is a

pervasive issue for children travelling both with and without their

families. While fleeing their country of origin, many unaccompanied children end up travelling with traffickers who may attempt to exploit them as workers.

Including adults, sex trafficking is more prevalent in Europe and

Central Asia, whereas in East Asia, South Asia, and the Pacific labour

trafficking is more prevalent.

Many unaccompanied children fleeing from conflict zones in Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, China, Afghanistan or Sri Lanka are forced into sexual exploitation.

Especially vulnerable groups include girls belonging to single-parent

households, unaccompanied children, children from child-headed

households, orphans, girls who were street traders, and girls whose

mothers were street traders.

While refugee boys have been identified as the main victims of

exploitation in the labor market, refugee girls aged between 13 and 18

have been the main targets of sexual exploitation. In particular, the number of young Nigerian women and girls brought into Italy

for exploitation has been increasing: it was reported that 3,529

Nigerian women, among them underage girls, arrived by sea between

January and June 2016. Once they reached Italy, these girls worked under

conditions of slavery, for periods typically ranging from three to

seven years.

Detention

Children may be detained

in prisons, military facilities, immigration detention centers, welfare

centers, or educational facilities. While detained, migrant children

are deprived of a range of rights, such as the right to physical and

mental health, privacy, education, and leisure. And many countries do

not have a legal time limit for detention, leaving some children

incarcerated for indeterminate time periods. Some children are even detained together with adults and subjected to a harsher, adult-based treatment and regimen.

In North Africa, children travelling without legal status are frequently subjected to extended periods of immigration detention. Children held in administrative detention in Palestine

only receive a limited amount of education, and those held in

interrogation centers receive no education at all. In two of the prisons

visited by Defense for Children International Palestine, education was

found to be limited to two hours a week.

It has also been reported that child administrative detainees in

Palestine do not receive sufficient food to meet their daily nutritional

requirements.

Documented cases of child detention are available for more than

100 countries, ranging from the highest to the lowest income nations. Even so, a growing number of countries, including both Panama and Mexico, prohibit the detention of child migrants. And Yemen

has adopted a community-driven approach, using small-group alternative

care homes for child refugees and asylum-seekers, as a more

age-appropriate way of detention.

In the United States unaccompanied children are placed in single

purpose non-secure “children’s shelters” for immigration violations,

rather than in juvenile detention facilities. However, this change has

not ended the practice of administrative detention entirely.

Although there is commitment by the Council of Europe to work toward

ending the detention of children for migration control purposes,

asylum-seeking and migrant children and families often undergo detention

experiences that conflict with international commitments.

Refugee camps

Some refugee camps

operate at levels below acceptable standards of environmental health;

overcrowding and a lack of wastewater networks and sanitation systems

are common.

Hardships of a refugee camp may also contribute to symptoms

following a refugee child's discharge from a camp. A small number of Cuban

refugee children and adolescents, who were detained in a refugee camp,

were assessed months after their release, and it was found that 57

percent of the youth exhibited moderate to severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Unaccompanied girls at refugee camps may also face harassment or assault from camp guards and fellow male refugees.

In addition to having poor infrastructure and limited support services,

there are a few refugee camps that can present danger to refugee

children and families by housing members of armed forces. Also, at a few

refugee camps, militia forces may try to recruit and abduct children.

Host country experiences (post-migration)

The

third stage, host country experiences, is the integration of refugees

into the social, political, economic, and cultural framework of the host

country society. The post-migration period involves adaptation to a new

culture and re-defining one's identity and place in the new society. This stress can be exacerbated when the children arrive in the host country and are expected to adapt quickly to a new setting.

It is only a minority of refugees who travel into new host

countries and who are allowed to start a new life there. Most refugees

are living in refugee camps or urban centres waiting to be able to

return home. For those who are starting a new life in a new country

there are two options:

Seeking asylum

Asylum seekers are people who have formally applied for asylum in another country and who are still waiting for a decision on their status.

Once they have received a positive response from the host government,

they will legally be considered as refugees. Refugees, like citizens of

the host country, have the rights to education, health, and social

services, whereas asylum seekers do not.

For instance, the majority of refugees and migrants who arrived

in Europe in 2015 through mid-2016 were accommodated in overcrowded

transit centers and informal settlements, where privacy and access to

education and health services were often limited. In some accommodation centers in Germany and Sweden,

where asylum seekers stayed until their claims were processed, separate

living spaces for women, as well as sex-separated latrines and shower

facilities, were unavailable.

Unaccompanied children

face particular difficulties throughout the asylum process. They are

minors who are separated from their families once they reach the host

country, or minors who decide to travel from their home countries to a

foreign country without a parent or guardian. More children are traveling alone, with nearly 100,000 unaccompanied children in 2015 filing claims for asylum in 78 countries.

Bhabha (2004) argues that it is more challenging for unaccompanied

children than adults to gain asylum, as unaccompanied children are

usually unable to find appropriate legal representation and stand up for

themselves during the application process. In Australia,

for instance, unaccompanied children, who usually do not have any kind

of legal assistance, must prove beyond any reasonable doubt that they

are in need of the country's protection.

Many children do not have the necessary documents for legal entry into a

host country, often avoiding officials due to fear of being caught and

deported to their home countries.

Without documented status, unaccompanied children often face challenges

in acquiring education and healthcare in many countries. These factors

make them particularly vulnerable to hunger, homelessness, and sexual

and labor exploitation. Displaced youth, both male and female, are vulnerable to recruitment into armed groups. Unaccompanied children may also resort to dangerous jobs to meet their own survival needs. Some may also engage in criminal activity or drug and alcohol abuse.

Girls, to a larger extent than boys, are vulnerable to sexual

exploitation and abuse, both of which can have far-reaching effects on

their physical and mental health.

Refugee resettlement

Third country resettlement refers

to the transfer of refugees from the country they have fled to another

country that is more suitable to their needs and that has agreed to

grant them permanent settlement.

Currently the number of places available for resettlement is less than

the number needed for children for whom resettlement would be most

appropriate. Some nations have prioritized children at risk as a category for resettlement.

The United States established its Unaccompanied Refugee Minor

Program in 1980 to support unaccompanied children for resettlement. The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) by the Department of Homeland Security

currently works with state and local service providers to provide

unaccompanied refugee children with resettlement and foster care

services. This service is guaranteed to unaccompanied refugee minors

until they reach the age of majority or until they are reunited with

their families.

Some European nations have established programs to support the resettlement and integration of refugee children.

The European countries admitting the most refugee children in 2016 via

resettlement were the United Kingdom (2,525 refugee children), Norway

(1,930), Sweden (915), and Germany (595). Together, these accounted for

66% of the child resettlement admissions to all of Europe. The United Kingdom

also established a new initiative in 2016 to support the resettlement

of vulnerable refugee children from the Middle East and North Africa,

regardless of family separation status.

It was reported in February 2017 that this program has been partially

suspended by the government; the program would no longer accept refugee

youth with "complex needs," such as those with disabilities, until

further notice.

Refugee children without caretakers have a greater risk of exhibiting

psychiatric symptoms of mental illnesses following traumatic stress. Unaccompanied refugee children display more behavioral problems and emotional distress than refugee children with caretakers.

Parental well-being plays a crucial role in enabling resettled refugees

to transition into a new society. If a child is separated from his/her

caretakers during the process of resettlement, the likelihood that

he/she will develop a mental illness increases.

Health

This section covers health throughout the different stages of the refugee experience.

Health status

Nutrition

Refugee children arriving in the United States often come from countries with a high prevalence of undernutrition.

Nearly half of a sample of refugee children who arrived to the American

state of Washington, the majority of which were from Iraq, Somalia, and

Burma, were found to have at least one form of malnutrition. In the

under five age range refugee children had significantly higher rates of wasting syndrome and stunted growth, as well as a lower prevalence of obesity, in comparison to low-income non-refugee children.

However, some time after they arrived in the United States and

Australia, many refugee children demonstrated an increasing rate of

overnutrition. An Australian study, assessing the nutritional status of

337 sub-Saharan African children aged between three and 12 years, found

that the prevalence rate for overweight amongt refugee children was

18.4%. The prevalence rate of overweight and obesity among refugee children in Rhode Island, increased from 17.3% at initial measurement at first arrival to 35.4% at measurement three years after.

But the nutritional profiles of refugee children also often vary

by their country of origin. A study involving Syrian refugee children in

Jordanian refugee camps found them to be on average more likely

overweight than acutely malnourished. The low prevalence of acute

malnutrition among them was attributed, at least partly, to UNICEF's

infant and child feeding interventions, as well as to the distribution

of food vouchers by the World Food Programme (WFP).

Among newly arrived refugees in Washington state, significantly

higher rates of obesity were observed among Iraqi children, whereas

higher rates of stunting were found among Burmese and Somali children.

The latter also had higher rates of wasting.

Such variation in the nutrition profiles of refugee children may be

explained by the variance in refugees' location and time in transition.

Communicable diseases

Communicable

diseases are a pervasive issue faced by refugee children in camps and

other temporary settlements. Governments and organizations are working

to address a number of them, such as measles, rubella, diarrhea, and

cholera. Refugee children often arrive in the United States from

countries with a high prevalence of infectious disease.

Measles has been a major cause of child deaths in refugee camps and among internally displaced people; measles also exacerbates malnutrition and vitamin A deficiency.

Some countries, such as Kenya, have developed preventative, detective,

and curative programs to specifically target measles within the refugee

children population. Kenya has reached over 20 million children with a

measles and rubella immunization campaign carried out at the national

level in May 2016. In 2017 the Kenya Ministry of Health even reported a

routine vaccination coverage of 95 percent in the Dadaab refugee camp.

As of April 2017, in response to the first confirmed cases of measles

in the camp, UNICEF and UNHCR have collaborated with the Kenya Ministry

of Health to swiftly implement an integrated measles vaccination program

in Dadaab. The campaign, which has been targeting children aged six to

14 years, also includes screening, treatment referrals for cases of

malnutrition, vitamin A supplementation, and deworming.

Diarrhea, acute watery diarrhea, and cholera

can also put children's lives at risk. Countries, such as Bangladesh,

have identified the introduction and development of proper sanitation

habits and facilities as potential solutions to these medical

conditions. A 2008 study comparing refugee camps in Bangladesh reported

that camps with sanitation facilities had cholera rates of 16%, whereas

camps without such facilities had cholera rates that were almost three

times higher.

In a single week in 2017, 5,011 cases of diarrhea in refugee camps in

Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh were reported. In response, UNICEF started a

year-long cholera vaccination campaign in October 2017, targeting all

children in the camps. At health centers in the refugee camps, UNICEF

has been screening for potential cholera cases and providing oral

rehydration salts. Community-based health workers are also going around

the camps to share information on the risks of acute watery diarrhea,

the cholera vaccination campaign, and the importance and necessity of

good hygiene practices.

Noncommunicable diseases

During

all points of the refugee experience, refugee children are often at

risk of developing several noncommunicable diseases and conditions, such

as lead poisoning, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and pediatric cancer.

Many refugee children come to their host countries with elevated

blood lead levels; others encounter lead hazards once they have

resettled. A study published in January 2013 found that the blood lead

levels of refugee children who had just arrived to the state of New

Hampshire were more than twice as likely to be above 10 µg/dL as the

blood lead levels of children born in the United States. Evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) in the United States also found that nearly 30% of 242 refugee

children in New Hampshire developed elevated blood lead levels within

three to six months of their arrival to the United States, even though

their levels were not found to be elevated at initial screening.

A more recent study reported that refugee children in Massachusetts

were 12 times more likely to have blood lead levels over 20 µg/dL a year

after an initial screening than non-refugee children of the same age

and living in the same communities.

A study analyzing the medical records of former refugees residing

in Rochester, New York between 1980 and 2012 demonstrated that former

child refugees may be at increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension following resettlement.

Many Afghan children lack access to urban diagnosis centers in

Pakistan; those who do have access have been found to have various types

of cancer.

It is also estimated that, within Turkey's Syrian refugee population,

60 to 100 children are diagnosed with cancer each year. Overall, the

incidence rate of pediatric cancers among Turkey's Syrian refugee

population was similar to that of Turkish children. The study

additionally noted, however, that most refugee children affected by

cancer were diagnosed when the tumor was already at an advanced stage.

This could indicate that refugee children and their families often face

obstacles such as poor prognoses, language barriers, financial problems,

and social problems in adapting to a new setting.

Mental health and illness

Traditionally,

the mental health of children experiencing conflict is understood in

terms of either post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or toxic stress.

Prolonged and constant exposure to stress and uncertainty,

characteristic of a war environment may result in toxic stress that

children express with a change in behavior that may include anxiety,

self-harm, aggressiveness or suicide.

A 2017 study conducted in Syria by Save the Children determined that

84% of all adults and most children considered ongoing bombing and

shelling to be the main psychological stressor, while 89% said that

children were more fearful as the war progressed, and 80% said that

children had become more aggressive. These stressors are leading causes

of the symptoms described above, which lead to diagnosis of PTSD and

toxic stress, among other mental conditions. These issues may then be

further exacerbated by a forced migration to a foreign country, and the

beginning of the process of refugee status determination.

Refugee children are extremely vulnerable during migration and

resettlement, and may experience long-term pathological effects, due to

"disrupted development time." Psychoanalysts of refugee health have

proposed that refugee children experience mourning for their culture and

countries, despite the fact that the war-torn state of their homes is

unsafe. This sudden loss of familiarity places children at a greater

risk for mental dysfunction. In addition, studies have shown that

refugee children show a higher vulnerability to stress when separated

from their families.

Studies from treatment facilities and small community samples have

confirmed that refugee youth are at higher risk for psychopathologic

disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, conduct

disorder, and problems resulting from substance abuse. However, it is

important to note that other large-scale community surveys have found

that the rate of psychiatric disorder among immigrant youth is not

higher than that of native-born children.

Nonetheless, experiments have shown that these adverse outcomes can be

prevented through adequate protective factors, such as social support

and intimacy.

Additionally, effective adaptation strategies, such as absorption in

work and creation of pseudofamilies, have led to successful coping in

refugees. Many refugee populations, particularly Southeast Asian,

undergo a secondary migration to larger communities of kinfolk from

their countries of origin, which serve as social support networks for

refugees. Research has shown that family reunification, formation of new

social groups, community groups, and social services and professional

support have contributed to successful resettlement of refugees.

Refugees can be stigmatized if they encounter mental health

deficiencies prior to and during their resettlement into a new society. Differences between parental and host country values can create a rift between the refugee child and his/her new society. Less exposure to stigmatization lowers the risk of refugee children developing PTSD.

Access to healthcare

Cognitive

and structural barriers make it difficult to determine the medical

service utilization rates and patterns of refugee children. A better

understanding of these barriers will help improve mental healthcare

access for refugee children and their families.

Cognitive and emotional barriers

Many

refugees develop a mistrust of authority figures due to repressive

governments in their country of origin. Fear of authority and a lack of

awareness regarding mental health issues prevent refugee children and

their families from seeking medical help.

Certain cultures use informal support systems and self-care strategies

to cope with their mental illnesses, rather than rely upon biomedicine. Language and cultural differences also complicate a refugee's understanding of mental illness and available healthcare.

Other factors that delay refugees from seeking medical help are:

- Fear of discrimination and stigmatization

- Denial of mental illness as defined in the Western context

- Fear of the unknown consequences following diagnosis such as deportation, separation from family, and losing children

- Mistrust of Western biomedicine

Language barriers

A

broad spectrum of translation services are available to all refugees,

but only a small number of those services are government-sponsored.

Community health organizations provide a majority of translation

services, but there are a shortage of funds and available programs.

Since children and adolescents have a greater capacity to adopt their

host country's language and cultural practices, they are often used as linguistic intermediaries between service providers and their parents.

This may result in increased tension in family dynamics where

culturally sensitive roles are reversed. Traditional family dynamics in

refugee families disturbed by cultural adaptation tend to destabilize

important cultural norms, which can create a rift between parent and

child. These difficulties cause an increase of depression, anxiety and

other mental health concerns in culturally-adapted adolescent refugees.

Relying on other family members or community members has equally

problematic results where relatives and community members

unintentionally exclude or include details relevant to comprehensive

care. Healthcare practitioners are also hesitant to rely on members of the community because it is breaches confidentiality.

A third party present also reduces the willingness of refugees to trust

their healthcare practitioners and disclose information.

Patients may receive a different translator for each of their follow-up

appointments with their mental healthcare providers, which means that

refugees need to recount their story via multiple interpreters, further

compromising confidentiality.

Culturally competent care

Culturally

competent care exists when healthcare providers have received

specialized training that helps them to identify the actual and

potential cultural factors informing their interactions with refugee

patients.

Culturally competent care tends to prioritize the social and cultural

determinants contributing to health, but the traditional Western

biomedical model of care often fails to acknowledge these determinants.

To provide culturally competent care to refugees, mental

healthcare providers should demonstrate some understanding of the

patient's background, and a sensitive commitment to relevant cultural

manners (for example: privacy, gender dynamics, religious customs, and

lack of language skills).

The willingness of refugees to access mental healthcare services rests

on the degree of cultural sensitivity within the structure of their

service provider.

The protective influence exercised by adult refugees on their

child and adolescent dependents makes it unlikely that young

adult-accompanied refugees will access mental healthcare services. Only

10-30 percent of youth in the general population, with a need for mental

healthcare services, are currently accessing care. Adolescent ethnic minorities are less likely to access mental healthcare services than youth in the dominant cultural group.

Parents, caretakers and teachers are more likely to report an

adolescent's need for help, and seek help resources, than the

adolescent.

Unaccompanied refugee minors are less likely to access mental

healthcare services than their accompanied counterparts. Internalizing

complaints (such as depression and anxiety) are prevalent forms of

psychological distress among refugee children and adolescents.

Other obstacles

Additional structural deterrents for refugees:

- Complicated insurance policies based on refugee status (e.g. Government Assistant Refugees vs. Non-), resulting in hidden costs for refugee patients According to the United States Office of Refugee Resettlement, an insurance called refugee Medical Assistance is available in the short term (up to 8 months), while other such as Medicaid and CHIP are available for several years.

- Lack of transportation

- A lack of public awareness and access to information about available resources

- An unfamiliarity with the host country's healthcare system, amplified by a shortage of government or community intervention in settlement services

Structural deterrents for healthcare professionals:

- Heightened instances of mental health complications in refugee populations

- A lack of documented medical history, which makes comprehensive care difficult

- Time constraints: medical appointments are restricted to a small window of opportunity, making it difficult to connect and provide mental healthcare for refugees

- Complicated insurance plans, resulting in a delay in compensation for the healthcare provider

Health education

The

World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts (WAGGGS) and Family

Health International (FHI) have designed and piloted a peer-centered

education program for adolescent refugee girls in Uganda, Zambia, and

Egypt. The goal of the program was to reach young women who were

interested in being informed about reproductive health issues. The

program was split into three age-specific groups: girls aged seven to 10

learned about bodily changes and anatomy; girls aged 11 to 14 learned

about sexually transmitted diseases; girls aged 15 and older focused on

tips to ensure a healthy pregnancy and to properly care for a baby.

According to qualitative surveys, increased self-esteem and greater use

of health services among the program's participants were the largest

benefits of the program.

Education

This

section covers education throughout the different stages of the refugee

experience. The report, "Left Behind: Refugee Education in Crisis,"

compares UNHCR sources and statistics on refugee education with data on school enrollment around the world provided by UNESCO,

the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

The report notes that, globally, 91 percent of children attend primary

school. For all refugees, that figure is at 61 percent. Specifically in

low-income countries, less than 50 percent of refugees are able to

attend primary school. As refugee children get older, school enrollment

rates drop: only 23 percent of refugee adolescents are enrolled in

secondary school, versus the global figure of 84 percent. In low-income

countries, nine percent of refugees are able to go to secondary school.

Across the world, enrollment in tertiary education stands at 36 percent.

For refugees, the percentage remains at one percent.

Adapting to a new school environment is a major undertaking for refugee children who arrive in a new country or refugee camp. Education is crucial for the sufficient psychosocial adjustment and cognitive growth of refugee children.

Due to these circumstances, it is important that educators consider the

needs, obstacles, and successful educational pathways for children

refugees.

Graham, Minhas, and Paxton (2016) note in their study

that parents' misunderstandings about educational styles, teachers' low

expectations and stereotyping tendencies, bullying and racial

discrimination, pre-migration and post-migration trauma, and forced

detention can all be risk factors for learning problems in refugee

children. They also note that high academic and life ambition, parents'

involvement in education, a supportive home and school environment,

teachers' understanding of linguistic and cultural heritage, and healthy

peer relationships can all contribute to a refugee child's success in

school.

While the initial purpose of refugee education was to prepare students

to return to their home countries, now the focus of American refugee

education is on integration.

Access to education

Structure of the education system

Schools

in North America lack the necessary resources for supporting refugee

children, particularly in negotiating their academic experience and in

addressing the diverse learning needs of refugee children.

Complex schooling policies that vary by classroom, building and

district, and procedures that require written communication or parent

involvement intimidate the parents of refugee children.

Educators in North America typically guess the grade in which refugee

children should be placed because there is not a standard test or formal

interview process required of refugee children.

Sahrawi refugee children learning Arabic and Spanish, math, reading and writing, and science subjects.

The ability to enroll in school and continue one's studies in developing countries is limited and uneven across regions and settings of displacement, particularly for young girls and at the secondary levels.

The availability of sufficient classrooms and teachers is low and many

discriminatory policies and practices prohibit refugee children from

attending school. Educational policies promoting age-caps can also be harmful to refugee children.

Many refugee children face legal restrictions to schooling, even

in countries of first asylum. This is the case especially for countries

that have not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol.

The 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol both emphasize the right to

education for refugees, articulating the definition of refugeehood in

international contexts. Nevertheless, refugee students have one of the

lowest rates of access to education. The UNHCR reported in 2014 that

about 50 percent of refugee children had access to education compared to

children globally at 93 percent. In countries where they lack official refugee status, refugee children are unable to enroll in national schools.

In Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, unregistered refugee children described

being hesitant to go to school, due to risk of encountering legal

authorities at school or while on the way to and from school.

Structure of classes

Student-teacher ratios are very high in most refugee schools, and in some countries, these ratios are nearly twice the UNCHR guideline of 40:1.

Although global policies and standards for refugee settings endorse

child-centered teaching methods that promote student participation,

teacher-centered instruction often predominates in refugee classrooms.

Teachers lecture for the majority of the time, offering few

opportunities for students to ask questions or engage in creative

thinking. In eight refugee-serving schools in Kenya, for example, lecturing was the primary mode of instruction.

In order to address the lack of attention to refugee education in

national school systems, the UNHCR developed formal relationships with

twenty national ministries of education in 2016 to oversee the political

commitment to refugee education at the nation-state level.

The UNCHR introduced an adaptive global strategy for refugee education

with the aim of "integration of refugee learners within national system

where possible and appropriate and as guided by ongoing consultation

with refugees".

Residence

Refugee children who live in large urban

centers in North America have a higher rate of success at school,

particularly because their families have greater access to additional

social services that can help address their specific needs.

Families who are unable to move to urban centers are at a disadvantage.

Children with unpredictable migration trajectories suffer most from a

lack of schooling because of a lack of uniform schooling in each of

their destinations before settling.

Language barriers and ethnicity

Acculturation stress occurs in North America when families expect refugee youth to remain loyal to ethnic values while mastering the host culture

in school and social activities. In response to this demand, children

may over-identify with their host culture, their culture of origin, or

become marginalized from both. Insufficient communication due to language

and cultural barriers may evoke a sense of alienation or "being the

other" in a new society. The clash between cultural values of the family

and popular culture in mainstream Western society leads to the

alienation of refugee children from their home culture.

Many Western schools do not address diversity among ethnic groups

from the same nation or provide resources for specific needs of

different cultures (such as including halal food in the school menu). Without successfully negotiating cultural differences in the classroom, refugee children experience social exclusion in their new host culture.

The presence of racial and ethnic discrimination can have an adverse

effect on the well-being of certain groups of children and lead to a

reduction in their overall school performance. For instance, cultural differences place Vietnamese refugee youth at a higher risk of pursuing disruptive behaviour. Contemporary Vietnamese American

adolescents are prone to greater uncertainties, self-doubts and

emotional difficulties than other American adolescents. Vietnamese

children are less likely to say they have much to be proud of, that they

like themselves as they are, that they have many good qualities, and

that they feel socially accepted.

Classes for refugees, more often than not, are taught in the host-country language.

Refugees in the same classroom may also speak several different

languages, requiring multiple interpretations; this can slow the pace of

overall instruction.

Refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo living in Uganda, for

example, had to transition from French to English. Some of these

children were placed in lower-level classes due to their lack of English

proficiency. Many older children therefore had to repeat lower-level

classes, even if they had already mastered the content. Using the language of one ethnic group as the instructional language may threaten the identity of a minority group.

The content of the curriculum can also act as a form of discrimination

against refugee children involved in the education systems of first

asylum countries.

Curricula often seem foreign and difficult to understand to refugees

who are attending national schools alongside host-country nationals. For

instance, in Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, children described having a

hard time understanding concepts that lacked relevance to their lived

experiences, especially concepts related to Kenyan history and

geography.

Similarly, in Uganda, refugee children from the Democratic Republic of

Congo studying together with Ugandan children in government schools did

not have opportunities in the curriculum to learn the history of their

home country.

The teaching of one-sided narratives, such as during history lessons,

can also threaten the identity of students belonging to minority groups.

Vietnamese refugee mother and children at a kindergarten in upper Afula, 1979.

Other obstacles

Although

high-quality education helps refugee children feel safe in the present

and enable them to be productive in the future, some do not find success

in school. Other obstacles may include:

- Disrupted schooling - refugee children may experience disruptive schooling in their country of origin, or they may receive no form of education at all. It is extremely difficult for a student with no previous education to enter a school full of educated children.

- Trauma - can impede the ability to learn and cause fear of people in positions of authority (such as teachers and principals)

- School drop outs - due to self-perceptions of academic ability, antisocial behaviour, rejection from peers and/or a lack of educational preparation prior to entering the host-country school. School drop outs may also be caused by unsafe school conditions, poverty, etc.

- Parents - when parental involvement and support are lacking, a child's academic success decreases substantially. Refugee parents are often unable to help their children with homework due to language barriers. Parents often do not understand the concept of parent-teacher meetings and/or never expect to be a part of their child's education due to pre-existing cultural beliefs.

- Assimilation - a refugee child's attempt to quickly assimilate into the culture of their school can cause alienation from their parents and country of origin and create barriers and tension between the parent and child.

- Social and individual rejection - hostile discrimination can cause additional trauma when refugee children and treated cruelly by their peers

- Identity confusion

- Behavioral issues - caused by the adjustment issues and survival behaviours learned in refugee camps

Role of teachers

North American schools are agents of acculturation, helping refugee children integrate into Western society.

Successful educators help children process trauma they may have

experienced in their country of origin while supporting their academic

adjustment.

Refugee children benefit from established and encouraged communication

between student and teacher, and also between different students in the

classroom. Familiarity with sign language and basic ESL strategies improves communication between teachers and refugee children. Also, non-refugee peers need access to literature that helps educate them on their refugee classmates experiences.

Course materials should be appropriate for the specific learning needs

of refugee children and provide for a wide range of skills in order to

give refugee children strong academic support.

Educators should spend time with refugee families discussing

previous experiences of the child in order to place the refugee child in

the correct grade level and to provide any necessary accommodations

School policies, expectations, and parent's rights should be translated

into the parent's native language since many parents do not speak

English proficiently. Educators need to understand the multiple demands

placed on parents (such as work and family care) and be prepared to

offer flexibility in meeting times with these families.

Academic adjustment of refugee children

Syrian refugee children attend a lesson in a UNICEF temporary classroom in northern Lebanon, July 2014

Teachers can make the transition to a new school easier for refugee children by providing interpreters.

Schools meet the psychosocial needs of children affected by war or

displacement through programs that provide children with avenues for

emotional expression, personal support, and opportunities to enhance

their understanding of their past experience.

Refugee children benefit from a case-by-case approach to learning,

because every child has had a different experience during their

resettlement. Communities where the refugee populations are bigger

should work with the schools to initiate after school, summer school, or

weekend clubs that give the children more opportunities to adjust to

their new educational setting.

Bicultural

integration is the most effective mode of acculturation for refugee

adolescents in North America. The staff of the school must understand

students in a community context and respect cultural differences.

Parental support, refugee peer support, and welcoming refugee youth

centers are successful in keeping refugee children in school for longer

periods of time.

Education about the refugee experience in North America also helps

teachers relate better with refugee children and understand the traumas

and issues a refugee child may have experienced.

Refugee children thrive in classroom environments where all

students are valued. A sense of belonging, as well as ability to

flourish and become part of the new host society, are factors predicting

the well-being of refugee children in academics. Increased school involvement and social interaction with other students help refugee children combat depression and/or other underlying mental health concerns that emerge during the post-migration period.

Peace education

Implemented

by UNICEF from 2012 to 2016 and funded by the Government of the

Netherlands, Peacebuilding, Education, and Advocacy (PBEA) was a program

that tested innovative education solutions to achieve peacebuilding

results. The PBEA program in Kenya's Dadaab refugee camp aimed to strengthen resilience and social cohesion in the camp, as well as between refugees and the host community.

The initiative was composed of two parts: the Peace Education Programme

(PEP), an in-school program taught in Dadaab's primary schools, and the

Sports for Development and Peace (SDP) program for refugee adolescents

and youth. There was anecdotal evidence of increased levels of social

cohesion from participation in PEP and potential resilience from

participation in SDP.

Peace education for refugee children may also have limitations and its share of opponents. Although peace education from past programs involving non-refugee populations reported to have had positive effects,

studies have found that the attitudes of parents and teachers can also

have a strong influence on students' internalization of peace values. Teachers from Cyprus also resisted a peace education program initiated by the government.

Another study found that, while teachers supported the prospect of

reconciliation, ideological and practical concerns made them uncertain

about the effective implementation of a peace education program.

Pedagogical Approaches

Refugees

fall into a unique situation where the nation-state may not adequately

address their educational needs, and the international relief system is

tasked with the role of a "pseudo-state" in developing a curriculum and

pedagogical approach.

Critical pedagogical approaches to refugee education address the

phenomenon of alienation that migrant students face in schools outside

of their home countries, where the positioning of English language

teachers and their students create power dynamics emphasizing the

inadequacies of foreign-language speakers, intensified by the use of

compensatory programs to cater to 'at-risk' students.

In order to adequately address state-less migrant populations,

curricula has to be relevant to the experiences of transnational youth.

Pedagogical researchers and policy makers can benefit from lessons

learned through participatory action research in refugee camps, where

student cited decreased self-esteem associated with a lack of education.

Disabilities

Children

with disabilities frequently suffer physical and sexual abuse,

exploitation, and neglect. They are often not only excluded from

education, but also not provided the necessary supports for realizing

and reaching their full potential.

In refugee camps and temporary shelters, the needs of children

with disabilities are often overlooked. In particular, a study surveying

Bhutanese refugee camps in Nepal, Burmese refugee camps in Thailand,

Somali refugee camps in Yemen, the Dadaab refugee camp

for Somali refugees in Kenya, and camps for internally displaced

persons in Sudan and Sri Lanka, found that many mainstream services

failed to adequately cater to the specific needs of children with

disabilities. The study reported that mothers in Nepal and Yemen have

been unable to receive formulated food for children with cerebral palsy

and cleft palates. The same study also found that, although children

with disabilities were attending school in all surveyed countries, and

refugee camps in Nepal and Thailand have successful programs that

integrate children with disabilities into schools, all other surveyed

countries have failed to encourage children with disabilities to attend

school. Similarly, Syrian parents consulted during a four-week field assessment conducted in northern and eastern Lebanon

in March 2013 reported that, since arriving in Lebanon, their children

with disabilities had not been attending school or engaging in other

educational activities.

In Jordan, too, Syrian refugee children with disabilities identified

lack of specialist educational care and physical inaccessibility as the

main barriers to their education.

Likewise, limited attention is being given to refugee children

with disabilities in the United Kingdom. It was reported in February

2017 that its government has decided to partially suspend the Vulnerable

Children's Resettlement Scheme, originally set to resettle 3,000

children with their families from countries in the Middle East and North

Africa. As a result of this suspension, no youth with complex needs,

including those with disabilities and learning difficulties, would be

accepted into the program until further notice.

Countries may often overlook refugee children with disabilities

with regards to humanitarian aid, because data on refugee children with

disabilities are limited. Roberts and Harris (1990) note that there is

insufficient statistical and empirical information on disabled refugees

in the United Kingdom.

While it was reported in 2013 that 26 percent of all Syrian refugees in

Jordan had impaired physical, intellectual, or sensory abilities, such

data specifically for children do not exist.