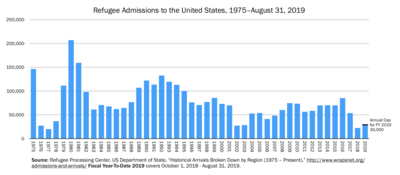

Annual Refugee Admissions to the United States by Fiscal Year, 1975 to mid-2018

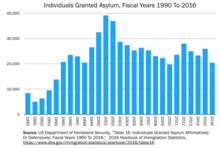

Annual Asylum Grants in the United States by Fiscal Year, 1990-2016

The United States recognizes the right of asylum for individuals as specified by international and federal law. A specified number of legally defined refugees who either apply for asylum from inside the U.S. or apply for refugee status from outside the U.S., are admitted annually. Refugees compose about one-tenth of the total annual immigration to the United States, though some large refugee populations are very prominent. Since World War II, more refugees have found homes in the U.S. than any other nation

and more than two million refugees have arrived in the U.S. since 1980.

In the years 2005 through 2007, the number of asylum seekers accepted

into the U.S. was about 40,000 per year. This compared with about 30,000

per year in the UK and 25,000 in Canada. The U.S. accounted for about

10% of all asylum-seeker acceptances in the OECD countries in 1998-2007. The United States is by far the most populous OECD country and receives fewer than the average number of refugees per capita: In 2010-14 (before the massive migrant surge in Europe in 2015) it ranked 28 of 43 industrialized countries reviewed by UNHCR.

Asylum has two basic requirements. First, an asylum applicant

must establish that he or she fears persecution in their home country. Second, the applicant must prove that he or she would be persecuted on account of one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or particular social group.

Character of refugee inflows and resettlement

Refugee resettlement to the United States by region, 1990–2005 (Source: Migration Policy Institute)

During the Cold War, and up until the mid-1990s, the majority of refugees resettled in the U.S. were people from the former-Soviet Union and Southeast Asia. The most conspicuous of the latter were the refugees from Vietnam following the Vietnam War, sometimes known as "boat people". Following the end of the Cold War, the largest resettled European group were refugees from the Balkans, primarily Serbs, from Bosnia and Croatia. In the 1990s/2000s, the proportion of Africans rose in the annual resettled population, as many fled various ongoing conflicts.

Large metropolitan areas have been the destination of most

resettlements, with 72% of all resettlements between 1983 and 2004 going

to 30 locations. The historical gateways for resettled refugees have been California (specifically Los Angeles, Orange County, San Jose, and Sacramento), the Mid-Atlantic region (New York in particular), the Midwest (specifically Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis-St. Paul), and Northeast (Providence, Rhode Island). In the last decades of the twentieth century, Washington, D.C.; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon; and Atlanta, Georgia

provided new gateways for resettled refugees. Particular cities are

also identified with some national groups: metropolitan Los Angeles

received almost half of the resettled refugees from Iran, 20% of Iraqi refugees went to Detroit, and nearly one-third of refugees from the former Soviet Union were resettled in New York.

Between 2004 and 2007, nearly 4,000 Venezuelans claimed political

asylum in the United States and almost 50% of them were granted. In

contrast, in 1996, only 328 Venezuelans claimed asylum, and a mere 20%

of them were granted. According to USA Today, the number of asylums being granted to Venezuelan claimants has risen from 393 in 2009 to 969 in 2012.

Other references agree with the high number of political asylum

claimants from Venezuela, confirming that between 2000 and 2010, the

United States has granted them with 4,500 political asylums.

Criticism

Despite

this, concerns have been raised with the U.S. asylum and refugee

determination processes. A recent empirical analysis by three legal

scholars described the U.S. asylum process as a game of refugee roulette;

that is to say that the outcome of asylum determinations depends in

large part on the personality of the particular adjudicator to whom an

application is randomly assigned, rather than on the merits of the case.

The very low numbers of Iraqi refugees accepted between 2003 and 2007

exemplifies concerns about the United States' refugee processes. The

Foreign Policy Association reported that "Perhaps the most perplexing

component of the Iraq refugee crisis... has been the inability for the

U.S. to absorb more Iraqis following the 2003 invasion of the country.

Up until 2008, the U.S. has granted less than 800 Iraqis refugee status,

just 133 in 2007. By contrast, the U.S. granted asylum to more than

100,000 Vietnamese refugees during the Vietnam War."

Relevant law and procedures

"The Immigration and Nationality Act ('INA') authorizes the Attorney General to grant asylum if an alien

is unable or unwilling to return to her country of origin because she

has suffered past persecution or has a well-founded fear of future

persecution on account of 'race, religion, nationality, membership in a

particular social group, or political opinion.'"

The United States is obliged to recognize valid claims for asylum under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees

and its 1967 Protocol. As defined by these agreements, a refugee is a

person who is outside their country of nationality (or place of habitual residence if stateless) who, owing to a fear of persecution

on account of a protected ground, is unable or unwilling to avail

himself of the protection of the state. Protected grounds include race,

nationality, religion, political opinion and membership of a particular social group. The signatories to these agreements are further obliged not to return or "refoul" refugees to the place where they would face persecution.

This commitment was codified and expanded with the passing of the Refugee Act of 1980 by the United States Congress.

Besides reiterating the definitions of the 1951 Convention and its

Protocol, the Refugee Act provided for the establishment of an Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS) to help refugees begin their lives in the U.S. The structure and

procedures evolved and by 2004, federal handling of refugee affairs was

led by the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) of the U.S. Department of State, working with the ORR at HHS. Asylum claims are mainly the responsibility of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Refugee quotas

Each year, the President of the United States

sends a proposal to the Congress for the maximum number of refugees to

be admitted into the country for the upcoming fiscal year, as specified

under section 207(e) (1)-(7) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

This number, known as the "refugee ceiling", is the target of annual

lobbying by both refugee advocates seeking to raise it and

anti-immigration groups seeking to lower it. However, once proposed, the

ceiling is normally accepted without substantial Congressional debate.

The September 11, 2001 attacks resulted in a substantial disruption to the processing of resettlement claims with actual admissions falling to about 26,000 in fiscal year

2002. Claims were doublechecked for any suspicious activity and

procedures were put in place to detect any possible terrorist

infiltration, though some advocates noted that, given the ease with

which foreigners can otherwise legally enter the U.S., entry as a

refugee is comparatively unlikely. The actual number of admitted

refugees rose in subsequent years with refugee ceiling for 2006 at

70,000. Critics note these levels are still among the lowest in 30

years.

| Recent actual, projected and proposed refugee admissions |

|---|

A total of 73,293 persons were admitted to the United States as

refugees during 2010. The leading countries of nationality for refugee

admissions were Iraq (24.6%), Burma (22.8%), Bhutan (16.9%), Somalia

(6.7%), Cuba (6.6%), Iran (4.8%), DR Congo (4.3%), Eritrea (3.5%),

Vietnam (1.2%) and Ethiopia (0.9%).

Application for resettlement by refugees abroad

The majority of applications for resettlement

to the United States are made to U.S. embassies in foreign countries

and are reviewed by employees of the State Department. In these cases,

refugee status has normally already been reviewed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and recognized by the host country. For these refugees, the U.S. has stated its preferred order of solutions are: (1) repatriation

of refugees to their country of origin, (2) integration of the refugees

into their country of asylum and, last, (3) resettlement to a third

country, such as the U.S., when the first two options are not viable.

The United States prioritizes valid applications for resettlement into three levels.

Priority One

- persons facing compelling security concerns in countries of first asylum; persons in need of legal protection because of the danger of refoulement; those in danger due to threats of armed attack in an area where they are located; or persons who have experienced recent persecution because of their political, religious, or human rights activities (prisoners of conscience); women-at-risk; victims of torture or violence, physically or mentally disabled persons; persons in urgent need of medical treatment not available in the first asylum country; and persons for whom other durable solutions are not feasible and whose status in the place of asylum does not present a satisfactory long-term solution. – UNHCR Resettlement Handbook

Priority Two

is

composed of groups designated by the U.S. government as being of

special concern. These are often identified by an act proposed by a

Congressional representative. Priority Two groups proposed for 2008

included:

- "Jews, Evangelical Christians, and Ukrainian Catholic and Orthodox religious activists in the former Soviet Union, with close family in the United States" (This is the amendment which was proposed by Senator Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J. and originally enacted November 21, 1989.)

- from Cuba: "human rights activists, members of persecuted religious minorities, former political prisoners, forced-labor conscripts (1965-68), persons deprived of their professional credentials or subjected to other disproportionately harsh or discriminatory treatment resulting from their perceived or actual political or religious beliefs or activities, and persons who have experienced or fear harm because of their relationship – family or social – to someone who falls under one of the preceding categories"

- from Vietnam: "the remaining active cases eligible under the former Orderly Departure Program (ODP) and Resettlement Opportunity for Vietnamese Returnees (ROVR) programs"; individuals who, through no fault of their own, were unable to access the ODP program before its cutoff date; and Amerasian citizens, who are counted as refugee admissions

- individuals who have fled Burma and who are registered in nine refugee camps along the Thai/Burma border and who are identified by UNHCR as in need of resettlement

- UNHCR-identified Burundian refugees who originally fled Burundi in 1972 and who have no possibility either to settle permanently in Tanzania or return to Burundi

- Bhutanese refugees in Nepal registered by UNHCR in the recent census and identified as in need of resettlement

- Iranian members of certain religious minorities

- Sudanese Darfurians living in a refugee camp in Anbar Governorate in Iraq would be eligible for processing if a suitable location can be identified

Priority Three

is reserved for cases of family reunification,

in which a refugee abroad is brought to the United States to be

reunited with a close family member who also has refugee status. A list

of nationalities eligible for Priority Three consideration is developed

annually. The proposed countries for FY2008 were Afghanistan, Burma, Burundi, Colombia, Congo (Brazzaville), Cuba, Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan and Uzbekistan.

Individual application

The minority of applications that are made by individuals who have

already entered the U.S. are judged on whether they meet the U.S.

definition of "refugee" and on various other statutory criteria

(including a number of bars that would prevent an otherwise-eligible

refugee from receiving protection). There are two ways to apply for

asylum while in the United States:

- If an asylum seeker has been placed in removal proceedings before an immigration judge with the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which is a part of the Department of Justice, the individual may apply for asylum with the Immigration Judge.

- If an asylum seeker is inside the United States and has not been placed in removal proceedings, he or she may file an application with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), regardless of their legal status in the United States. However, if the asylum seeker is not in valid immigration status and USCIS does not grant the asylum application, USCIS may place the applicant in removal proceedings, in that case a judge will consider the application anew. The immigration judge may also consider the applicant for relief that the asylum office has no jurisdiction to grant, such as withholding of removal and protection under the Convention Against Torture. Since the effective date of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act passed in 1996, an applicant must apply for asylum within one year of entry or be barred from doing so unless the applicant can establish changed circumstances that are material to their eligibility for asylum or exceptional circumstances related to the delay.

Immigrants who were picked up after entering the country between

entry points can be released by Immigration and Customs Enforcement

(ICE) on payment of a bond,

and an immigration judge may lower or waive the bond. In contrast,

refugees who asked for asylum at an official point of entry before

entering the U.S. cannot be released on bond. Instead, ICE officials

have full discretion to decide whether they can be released.

If an applicant is eligible for asylum, they have a procedural right to have the Attorney General

make a discretionary determination as to whether the applicant should

be admitted into the United States as an asylee. An applicant is also

entitled to mandatory "withholding of removal" (or restriction on

removal) if the applicant can prove that her life or freedom would be

threatened upon return to her country of origin. The dispute in asylum

cases litigated before the Executive Office for Immigration Review

and, subsequently, the federal courts centers on whether the

immigration courts properly rejected the applicant's claim that she is

eligible for asylum or other relief.

The applicant has the burden of proving that he (or she) is

eligible for asylum. To satisfy this burden, an applicant must show that

she has a well-founded fear of persecution in her home country on

account of either race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or

membership in a particular social group.

The applicant can demonstrate her well-founded fear by demonstrating

that she has a subjective fear (or apprehension) of future persecution

in her home country that is objectively reasonable. An applicant's claim

for asylum is stronger where she can show past persecution, in which

case she will receive a presumption that she has a well-founded fear of

persecution in her home country. The government can rebut this

presumption by demonstrating either that the applicant can relocate to

another area within her home country in order to avoid persecution, or

that conditions in the applicant's home country have changed such that

the applicant's fear of persecution there is no longer objectively

reasonable. Technically, an asylum applicant who has suffered past

persecution meets the statutory criteria to receive a grant of asylum

even if the applicant does not fear future persecution. In practice,

adjudicators will typically deny asylum status in the exercise of

discretion in such cases, except where the past persecution was so

severe as to warrant a humanitarian grant of asylum, or where the

applicant would face other serious harm if returned to their country of

origin. In addition, applicants who, according to the US Government,

participated in the persecution of others are not eligible for asylum.

A person may face persecution in their home country because of

race, nationality, religion, ethnicity, or social group, and yet not be

eligible for asylum because of certain bars defined by law. The most

frequent bar is the one-year filing deadline. If an application is not

submitted within one year following the applicant's arrival in the

United States, the applicant is barred from obtaining asylum unless

certain exceptions apply. However, the applicant can be eligible for

other forms of relief such as Withholding of Removal, which is a less

favorable type of relief than asylum because it does not lead to a Green

Card or citizenship. The deadline for submitting the application is not

the only restriction that bars one from obtaining asylum. If an

applicant persecuted others, committed a serious crime, or represents a

risk to U.S. security, he or she will be barred from receiving asylum as

well.

- After 2001, asylum officers and immigration judges became less likely to grant asylum to applicants, presumably because of the attacks on 11 September.

In 1986 an Immigration Judge agreed not to send Fidel Armando-Alfanso back to Cuba, based on his membership in a particular social group (gay people) who were persecuted and feared further persecution by the government of Cuba. The Board of Immigration Appeals upheld the decision in 1990, and in 1994, then-Attorney General Janet Reno

ordered this decision to be a legal precedent binding on Immigration

Judges and the Asylum Office, and established sexual orientation as a

grounds for asylum. However, in 2002 the Board of Immigration Appeals

“suggested in an ambiguous and internally inconsistent decision that

the ‘protected characteristic’ and ‘social visibility’ tests may

represent dual requirements in all social group cases.”

The requirement for social visibility means that the government of a

country from which the person seeking asylum is fleeing must recognize

their social group, and that LGBT

people who hide their sexual orientation, for example out of fear of

persecution, may not be eligible for asylum under this mandate.

In 1996 Fauziya Kasinga,

a 19-year-old woman from the Tchamba-Kunsuntu people of Togo, became

the first person to be granted asylum in the United States to escape female genital mutilation. In August 2014, the Board of Immigration Appeals, the United States's highest immigration court, found for the first time that women who are victims of severe domestic violence in their home countries can be eligible for asylum in the United States. However, that ruling was in the case of a woman from Guatemala and was anticipated to only apply to women from there. On June 11, 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed that precedent and announced that victims of domestic abuse or gang violence will no longer qualify for asylum.

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca precedent

The term "well-founded fear" has no precise definition in asylum law. In INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421

(1987), the Supreme Court avoided attaching a consistent definition to

the term, preferring instead to allow the meaning to evolve through

case-by-case determinations. However, in Cardoza-Fonseca, the

Court did establish that a "well-founded" fear is something less than a

"clear probability" that the applicant will suffer persecution. Three

years earlier, in INS v. Stevic, 467 U.S. 407

(1984), the Court held that the clear probability standard applies in

proceedings seeking withholding of deportation (now officially referred

to as 'withholding of removal' or 'restriction on removal'), because in

such cases the Attorney General must allow the applicant to remain in

the United States. With respect to asylum, because Congress employed

different language in the asylum statute and incorporated the refugee

definition from the international Convention relating to the Status of

Refugees, the Court in Cardoza-Fonseca reasoned that the standard for showing a well-founded fear of persecution must necessarily be lower.

An applicant initially presents his claim to an asylum officer,

who may either grant asylum or refer the application to an Immigration

Judge. If the asylum officer refers the application and the applicant is

not legally authorized to remain in the United States, the applicant is

placed in removal proceedings. After a hearing, an immigration judge

determines whether the applicant is eligible for asylum. The immigration

judge's decision is subject to review on two, and possibly three,

levels. First, the immigration judge's decision can be appealed to the Board of Immigration Appeals.

In 2002, in order to eliminate the backlog of appeals from immigration

judges, the Attorney General streamlined review procedures at the Board of Immigration Appeals.

One member of the Board can affirm a decision of an immigration judge

without oral argument; traditional review by three-judge panels is

restricted to limited categories for which "searching appellate review"

is appropriate. If the BIA affirms the decision of the immigration

court, then the next level of review is a petition for review in the United States court of appeals

for the circuit in which the immigration judge sits. The court of

appeals reviews the case to determine if "substantial evidence" supports

the immigration judge's (or the BIA's) decision. As the Supreme Court held in INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12 (2002), if the federal appeals court determines that substantial evidence does not

support the immigration judge's decision, it must remand the case to

the BIA for further proceedings instead of deciding the unresolved legal

issue in the first instance. Finally, an applicant aggrieved by a

decision of the federal appeals court can petition the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case by a discretionary writ of certiorari. But the Supreme Court has no duty to review an immigration case, and so many applicants for asylum forego this final step.

Notwithstanding his statutory eligibility, an applicant for asylum will be deemed ineligible if:

- the applicant participated in persecuting any other person on account of that other person's race, religion, national origin, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the community because he has been convicted in the United States of a particularly serious crime;

- the applicant has committed a serious non-political crime outside the United States prior to arrival;

- the applicant constitutes a danger to the security of the United States;

- the applicant is inadmissible on terrorism-related grounds;

- the applicant has been firmly resettled in another country prior to arriving in the United States; or

- the applicant has been convicted of an aggravated felony as defined more broadly in the immigration context.

Conversely, even if an applicant is eligible for asylum, the Attorney

General may decline to extend that protection to the applicant. (The

Attorney General does not have this discretion if the applicant has also

been granted withholding of deportation.) Frequently the Attorney

General will decline to extend an applicant the protection of asylum if

he has abused or circumvented the legal procedures for entering the

United States and making an asylum claim.

Work permit and permanent residence status

An in-country applicant for asylum is eligible for a work permit

(employment authorization) only if their application for asylum has

been pending for more than 150 days without decision by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

(USCIS) or the Executive Office for Immigration Review. If an asylum

seeker is recognized as a refugee, he or she may apply for lawful

permanent residence status (a green card) one year after being granted

asylum. Asylum seekers generally do not receive economic support. This,

combined with a period where the asylum seeker is ineligible for a work

permit is unique among developed countries and has been condemned from

some organisations, including Human Rights Watch.

Up until 2004, recipients of asylee status faced a wait of

approximately fourteen years to receive permanent resident status after

receiving their initial status, because of an annual cap of 10,000 green

cards for this class of individuals. However, in May 2005, under the

terms of a proposed settlement of a class-action lawsuit, Ngwanyia v. Gonzales,

brought on behalf of asylees against CIS, the government agreed to make

available an additional 31,000 green cards for asylees during the

period ending on September 30, 2007. This is in addition to the 10,000

green cards allocated for each year until then and was meant to speed up

the green card waiting time considerably for asylees. However, the

issue was rendered somewhat moot by the enactment of the REAL ID Act of 2005

(Division B of United States Public Law 109-13 (H.R. 1268)), which

eliminated the cap on annual asylee green cards. Currently, an asylee

who has continuously resided in the US for more than one year in that

status has an immediately available visa number.

On April 29, 2019, President Trump

ordered new restrictions on asylum seekers at the Mexican border —

including application fees and work permit restraints — and directed

that cases in the already clogged immigration courts be settled within

180 days.

Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program

An Unaccompanied Refugee Minor

(URM) is any person who has not attained 18 years of age who entered

the United States unaccompanied by and not destined to: (a) a parent,

(b) a close non-parental adult relative who is willing and able to care

for said minor, or (c) an adult with a clear and court-verifiable claim

to custody of the minor; and who has no parent(s) in the United States. These minors are eligible for entry into the URM program. Trafficking victims who have been certified by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the United States Department of Homeland Security, and/or the United States Department of State are also eligible for benefits and services under this program to the same extent as refugees.

The URM program is coordinated by the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), a branch of the United States Administration for Children and Families.

The mission of the URM program is to help people in need “develop

appropriate skills to enter adulthood and to achieve social

self-sufficiency.” To do this, URM provides refugee minors with the same

social services available to U.S.-born children, including, but not

limited to, housing, food, clothing, medical care, educational support,

counseling, and support for social integration.

History of the URM Program

URM was established in 1980 as a result of the legislative branch's enactment of the Refugee Act that same year.

Initially, it was developed to “address the needs of thousands of

children in Southeast Asia” who were displaced due to civil unrest and

economic problems resulting from the aftermath of the Vietnam War, which

had ended only five years earlier.

Coordinating with the United Nations and “utilizing an executive order

to raise immigration quotas, President Carter doubled the number of

Southeast Asian refugees allowed into the United States each month.” The URM was established, in part, to deal with the influx of refugee children.

URM was established in 1980, but the emergence of refugee minors as an issue in the United States “dates back to at least WWII.”

Since that time, oppressive regimes and U.S. military involvement have

consistently “contributed to both the creation of a notable supply of

unaccompanied refugee children eligible to relocate to the United

States, as well as a growth in public pressure on the federal government

to provide assistance to these children."

Since 1980, the demographic makeup of children within URM has

shifted from being largely Southeast Asian to being much more diverse.

Between 1999 and 2005, children from 36 different countries were

inducted into the program.

Over half of the children who entered the program within this same time

period came from Sudan, and less than 10% came from Southeast Asia.

Perhaps the most commonly known group to enter the United States

through the URM program was known as the “Lost Boys” of Sudan. Their

story was made into a documentary by Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk. The film, Lost Boys of Sudan, follows two Sudanese refugees on their journey from Africa to America. It won an Independent Spirit Award and earned two national Emmy nominations.

Functionality

In terms of functionality, the URM program is considered a

state-administered program. The U.S. federal government provides funds

to certain states that administer the URM program, typically through a

state refugee coordinator's office. The state refugee coordinator

provides financial and programmatic oversight to the URM programs in

their state. The state refugee coordinator ensures that unaccompanied

minors in URM programs receive the same benefits and services as other

children in out-of-home care in the state. The state refugee coordinator

also oversees the needs of unaccompanied minors with many other

stakeholders.

ORR contracts with two faith-based agencies to manage the URM program in the United States; Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS) and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

(USCCB). These agencies identify eligible children in need of URM

services; determine appropriate placements for children among their

national networks of affiliated agencies; and conduct training, research

and technical assistance on URM services. They also provide the social

services such as: indirect financial support for housing, food,

clothing, medical care and other necessities; intensive case management

by social workers; independent living skills training; educational

supports; English language training; career/college counseling and

training; mental health services; assistance adjusting immigration

status; cultural activities; recreational opportunities; support for

social integration; and cultural and religious preservation.

The URM services provided through these contracts are not

available in all areas of the United States. The 14 states that

participate in the URM program include: Arizona, California, Colorado,

Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, New York,

Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington and the nation's

capital, Washington D.C.

Adoption of URM Children

Although they are in the United States without the protection of

their family, URM-designated children are not generally eligible for

adoption. This is due in part to the Hague Convention on the Protection

and Co-Operation in Respect of Inter-Country Adoption, otherwise known

as the Hague Convention. Created in 1993, the Hague Convention established international standards for inter-country adoption. In order to protect against the abduction, sale or trafficking of children,

these standards protect the rights of the biological parents of all

children. Children in the URM program have become separated from their

biological parents and the ability to find and gain parental release of

URM children is often extremely difficult. Most children, therefore, are

not adopted. They are served primarily through the foster care system

of the participating states. Most will be in the custody of the state

(typically living with a foster family) until they become adults.

Reunification with the child's family is encouraged whenever possible.

U.S. government support after arrival

As

soon as people seeking asylum in the United States are accepted as

refugees they are eligible for public assistance just like any other

person, including cash welfare, food assistance, and health coverage.

Many refugees depend on public benefits, but over time may become

self-sufficient.

Availability of public assistance programs can vary depending on

which states within the United States refugees are allocated to resettle

in. For example, health policies differ from state to state, and as of

2017, only 33 states expanded Medicaid programs under the Affordable Care Act.

In 2016, The American Journal of Public Health reported that only 60%

of refugees are assigned to resettlement locations with expanding

Medicaid programs, meaning that more than 1 in 3 refugees may have

limited healthcare access.

In 2015, the world saw the greatest displacement of people since

World War II with 65.3 million people having to flee their homes. In fiscal year 2016, the Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration under the Migration and Refugee Assistance Act

(MRA) requested that $442.7 million be allocated to refugee admission

programs that relocate refugees into communities across the country.

President Obama made a "Call to Action" for the private sector to make a

commitment to help refugees by providing opportunities for jobs and

accommodating refugee accessibility needs.

Child separation

The recent U.S. Government policy known as "Zero-tolerance" was implemented in April 2018. In response, a number of scientific organizations released statements on the negative impact of child separation, a form of childhood trauma, on child development, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, and the Society for Research in Child Development.

Efforts are underway to minimize the impact of child separation.

For instance, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network released a resource guide and held a webinar related to traumatic separation and refugee and immigrant trauma.

LGBTQ asylum seekers

Historically, homosexuality was considered a deviant behavior in the US, and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 barred homosexual individuals from entering the United States due to concerns about their psychological health. One of the first successful LGBT

asylum pleas to be granted refugee status in the United States due to

sexual orientation was a Cuban national whose case was first presented

in 1989.

The case was affirmed by the Board of Immigration Appeals and the

barring of LGBT and queer individuals into the United States was

repealed in 1990. The case, known as Matter of Acosta (1985), set

the standard of what qualified as a "particular social group." This new

definition of "social group" expanded to explicitly include

homosexuality and the LGBT population. It considers homosexuality and gender identity

a "common characteristic of the group either cannot change or should

not be required to change because it is fundamental to their individual

identities or consciences."

This allows political asylum to some LGBT individuals who face

potential criminal penalties due to homosexuality and sodomy being

illegal in the home country who are unable to seek protection from the

state.

The definition was intended to be open-ended in order to fit with the

changing understanding of sexuality. According to Fatma Marouf, the

definition established in Acosta was influential internationally, appealing to "the fundamental norms of human rights."

Experts disagree on the role of sexuality in the asylum process.

Stefan Volger argues that the definition of social group tends to be

relatively flexible, and describes sexuality akin to religion—one might

change religions but characteristics of religion are protected traits

that can't be forced.

However, Susan Berger argues that while homosexuality and other sexual

minorities might be protected under the law, the burden of proving that

they are an LGBT member demonstrates a greater immutable view of the

expected LGBT performance.

The importance of visibility is stressed throughout the asylum process,

as sexuality is an internal characteristic. It is not visibly

represented in the outside appearance.

When considering how sexuality is viewed, research utilize asylum

claim decisions and individual cases to understand what is considered

characteristic of being a member of the LGBT community. In migration

studies, there was an implicit assumption that immigrants are

heterosexual and LGBT people are citizens.

One theory that took route within the queer migrations studies was Jasbir Puar's idea of homonationalism.

According to Paur, following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack,

the movement against terrorists also resulted in a reinforcement of the

binary "us vs. them" against some members of the LGBT community. The

social landscape was termed "homonormative nationalism" or

homonationalism.

According to Amanda M. Gómez, sexual orientation identity is formed and performed in the asylum process.

Unlike race or gender, in sexual orientation asylum claims, applicants

have to prove their sexuality to convince asylum officials that they are

truly part of their social group.

Rachel Lewis and Nancy Naples argue that LGBT people may not seem

credible if they do not fit Western stereotypes of what LGBT people look

like. The expectation is that lesbians will present in masculine ways, while gay men will present in feminine ways.

Eithne Luibhéid recognizes this presentation issue as connecting to the

mainstream narrative that same-sex attraction comes from a problem of

women being trapped in the men's body and vice-versa.

Dress, mannerisms, and style of speech, as well as not having had

public romantic relationships with the opposite sex, may be perceived by

the immigration judge as not reflective of the applicants’ sexual

orientation.

Scholars and legal experts have long argued that asylum law has created

legal definitions for homosexuality that are essentialist and damaging

for our understanding of queerness.

Obstacles asylum seekers face

Gender

Female

asylum seekers may encounter issues when seeking asylum in the United

States due to what some see as a structural preference for male

narrative forms in the requirements for acceptance.

Researchers, such as Amy Shuman and Carol Bohmer, argue that the asylum

process produces gendered cultural silences, particular in hearings

where the majority of narrative construction takes place. Cultural silences refers to things that women refrain from sharing, due to shame, humiliation, and other deterrents.

These deterrents can make achieving asylum more difficult as it can

keep relevant information from being shared with the asylum judge.

Susan Berger argues that the relationship between gender and

sexuality leads to arbitrary case decisions, as there are no clear

guidelines for when the private problems becomes an international

problem. Berger uses case specific examples of asylum applications where

gender and sexuality both act as an immutable characteristic. She

argues that because male persecutors of lesbian and heterosexual female

applicants tend to be family members, their harm occurs in the private

domain and is therefore excluded from asylum consideration. Male

applicants, on the other hand, are more likely to experience targeted,

public persecution that relates better to the traditional idea of a

homosexual asylum seeker. Male applicants are encouraged to perform gay

stereotypes to strengthen their asylum application on the basis of

sexual orientation, while lesbian women face the same difficulties as

their heterosexual partners to perform the homosexual narrative.

Joe Rollins found that gay male applicants were more likely to be

granted refugee status if they included rape in their narratives, while

gay Asian immigrants were less likely to be granted refugee status over

all, even with the inclusion of rape. This, he claimed, was due to Asian men being subconsciously feminized.

These experiences are articulated during the hearing process where the responsibility to prove membership is on the applicant.

During the hearing process, applicants are encouraged to demonstrate

persecution for gender or sexuality and place the source as their own

culture. Shuman and Bohmer argue that in sexual minorities, it is not

enough to demonstrate only violence, asylum applicants have to align

themselves against a restrictive culture. The narratives are forced to

fit into categories shaped by western culture or be found to be

fraudulent.

According to Shuman and Bohmer, due to women's social position in

most countries, lesbians are more likely to stay in the closet, which

often means that they do not have the public visibility element that the

asylum process requires for credibility.

This leads to Lewis and Naples’ critique to the fact that asylum

officials often assume that since women do not live such public lives as

men do, that they would be safe from abuse or persecution, in

comparison to gay men who are often part of the public sphere.

This argument violates the basic concept that one's sexual orientation

is a fundamental right and that family and the private sphere are often

the first spaces where lesbians experience violence and discrimination.

Because lesbians live such hidden lives, they tend to lack police

reports, hospital records, and letters of support from witnesses, which

decreases their chances of being considered credible and raises the

stakes of effectively telling their stories in front of asylum

officials.

Mexican Transgender Asylum Seeker

LGBT

individuals have a higher risk for mental health problems when compared

to cis-gender counterparts and many transgender individuals face

socioeconomic difficulties in addition to being an asylum seeker. In a

study conducted by Mary Gowin, E. Laurette Taylor, Jamie Dunnington,

Ghadah Alshuwaiyer, and Marshall K. Cheney of Mexican Transgender Asylum

Seekers, they found 5 major stressors among the participants including

assault (verbal, physical and sexual), "unstable environments, fear for

safety and security, hiding undocumented status, and economic

insecurity."

They also found that all of the asylum seekers who participated

reported at least one health issue that could be attributed to the

stressors. They accessed little or no use of health or social services,

attributed to barriers to access, such as fear of the government,

language barriers and transportation.

They are also more likely to report lower levels of education due to

few opportunities after entering the United States. Many of the asylum

seeker participants entered the United States as undocumented

immigrants. Obstacles to legal services included fear and knowledge that

there were legal resources to gaining asylum.

Human Rights Activism

Human

Rights and LGBT advocates have worked to create many improvements to

the LGBT Asylum Seekers coming into the United States.

A 2015 report issued by the LGBT Freedom and Asylum network identifies

best practices for supporting LGBT asylum seekers in the US. The US State Department has also issued a factsheet on protecting LGBT refugees.

Film

The 2000 documentary film Well-Founded Fear, from filmmakers Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini marked the first time that a film crew was privy to the private proceedings at the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS),

where individual asylum officers ponder the often life-or-death fate of

the majority of immigrants seeking asylum. The film analyzes the US

asylum application process by following several asylum applicants and

asylum officers.