A slum is a highly populated urban residential area consisting mostly of closely packed, decrepit housing units in a situation of deteriorated or incomplete infrastructure, inhabited primarily by impoverished persons. While slums differ in size and other characteristics, most lack reliable sanitation services, supply of clean water, reliable electricity, law enforcement and other basic services. Slum residences vary from shanty houses to professionally built dwellings which, because of poor-quality construction or provision of basic maintenance, have deteriorated.

Due to increasing urbanization of the general populace, slums became common in the 18th to late 20th centuries in the United States and Europe. Slums are still predominantly found in urban regions of developing countries, but are also still found in developed economies.

According to UN-Habitat, around 33% of the urban population in the developing world in 2012, or about 863 million people, lived in slums. The proportion of urban population living in slums in 2012 was highest in Sub-Saharan Africa (62%), followed by Southern Asia (35%), Southeastern Asia (31%), Eastern Asia (28%), Western Asia (25%), Oceania (24%), Latin America and the Caribbean (24%), and North Africa (13%). Among individual countries, the proportion of urban residents living in slum areas in 2009 was highest in the Central African Republic (95.9%). Between 1990 and 2010 the percentage of people living in slums dropped, even as the total urban population increased. The world's largest slum city is found in the Neza-Chalco-Ixtapaluca area, located in the State of Mexico.

Slums form and grow in different parts of the world for many different reasons. Causes include rapid rural-to-urban migration, economic stagnation and depression, high unemployment, poverty, informal economy, forced or manipulated ghettoization, poor planning, politics, natural disasters and social conflicts. Strategies tried to reduce and transform slums in different countries, with varying degrees of success, include a combination of slum removal, slum relocation, slum upgrading, urban planning with citywide infrastructure development, and public housing.

Etymology and nomenclature

It is thought that slum is a British slang word from the East End of London meaning "room", which evolved to "back slum" around 1845 meaning 'back alley, street of poor people.'

Numerous other non English terms are often used interchangeably with slum: shanty town, favela, rookery, gecekondu, skid row, barrio, ghetto,

bidonville, taudis, bandas de miseria, barrio marginal, morro,

loteamento, barraca, musseque, tugurio, solares, mudun safi, karyan,

medina achouaia, brarek, ishash, galoos, tanake, baladi, trushebi,

chalis, katras, zopadpattis, bustee, estero, looban, dagatan, umjondolo,

watta, udukku, and chereka bete.

The word slum has negative connotations, and using this

label for an area can be seen as an attempt to delegitimize that land

use when hoping to repurpose it.

History

One of the many New York City slum photographs of Jacob Riis (ca 1890). Squalor can be seen in the streets, wash clothes hanging between buildings.

Inside of a slum house, from Jacob Riis photo collection of New York City (ca 1890).

Part of Charles Booth's poverty map showing the Old Nichol, a slum in the East End of London. Published 1889 in Life and Labour of the People in London.

The red areas are "middle class, well-to-do", light blue areas are

"poor, 18s to 21s a week for a moderate family", dark blue areas are

"very poor, casual, chronic want", and black areas are the "lowest

class...occasional labourers, street sellers, loafers, criminals and

semi-criminals".

Slums were common in the United States and Europe before the early

20th century. London's East End is generally considered the locale where

the term originated in the 19th century, where massive and rapid

urbanisation of the dockside and industrial areas led to intensive

overcrowding in a warren of post-medieval streetscape. The suffering of

the poor was described in popular fiction by moralist authors such as Charles Dickens – most famously Oliver Twist (1837-9) and echoed the Christian Socialist values of the time, which soon found legal expression in the Public Health Act of 1848. As the slum clearance movement gathered pace, deprived areas such as Old Nichol were fictionalised to raise awareness in the middle classes in the form of moralist novels such as A Child of the Jago (1896) resulting in slum clearance and reconstruction programmes such as the Boundary Estate (1893-1900) and the creation of charitable trusts such as the Peabody Trust founded in 1862 and Joseph Rowntree Foundation (1904) which still operate to provide decent housing today.

Slums are often associated with Victorian Britain,

particularly in industrial English towns, lowland Scottish towns and

Dublin City in Ireland. Engels described these British neighborhoods as

"cattle-sheds for human beings". These were generally still inhabited until the 1940s, when the British government started slum clearance and built new council houses.

There are still examples left of slum housing in the UK, but many have

been removed by government initiative, redesigned and replaced with

better public housing.

In Europe, slums were common.

By the 1920s it had become a common slang expression in England,

meaning either various taverns and eating houses, "loose talk" or gypsy

language, or a room with "low going-ons". In Life in London Pierce Egan used the word in the context of the "back slums" of Holy Lane or St Giles. A footnote defined slum to mean "low, unfrequent parts of the town". Charles Dickens

used the word slum in a similar way in 1840, writing "I mean to take a

great, London, back-slum kind walk tonight". Slum began to be used to

describe bad housing soon after and was used as alternative expression

for rookeries. In 1850 the Catholic Cardinal Wiseman described the area known as Devil's Acre in Westminster, London as follows:

Close under the Abbey of Westminster there lie concealed labyrinths of lanes and potty and alleys and slums, nests of ignorance, vice, depravity, and crime, as well as of squalor, wretchedness, and disease; whose atmosphere is typhus, whose ventilation is cholera; in which swarms of huge and almost countless population, nominally at least, Catholic; haunts of filth, which no sewage committee can reach – dark corners, which no lighting board can brighten.

This passage was widely quoted in the national press, leading to the popularisation of the word slum to describe bad housing.

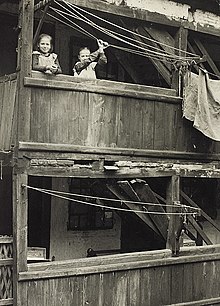

A slum dwelling in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, about 1936.

In France as in most industrialised European capitals, slums were

widespread in Paris and other urban areas in the 19th century, many of

which continued through first half of the 20th century. The first

cholera epidemic of 1832 triggered a political debate, and Louis René

Villermé study of various arrondissements of Paris demonstrated the differences and connection between slums, poverty and poor health. Melun Law

first passed in 1849 and revised in 1851, followed by establishment of

Paris Commission on Unhealthful Dwellings in 1852 began the social

process of identifying the worst housing inside slums, but did not

remove or replace slums. After World War II, French people started mass

migration from rural to urban areas of France. This demographic and

economic trend rapidly raised rents of existing housing as well as

expanded slums. French government passed laws to block increase in the

rent of housing, which inadvertently made many housing projects

unprofitable and increased slums. In 1950, France launched its Habitation à Loyer Modéré initiative to finance and build public housing and remove slums, managed by techniciens – urban technocrats, financed by Livret A – a tax free savings account for French public.

New York City is believed to have created United States first slum, named the Five Points in 1825, as it evolved into a large urban settlement. Five Points was named for a lake named Collect.

which, by the late 1700s, was surrounded by slaughterhouses and

tanneries which emptied their waste directly into its waters. Trash

piled up as well and by the early 1800s the lake was filled up and dry.

On this foundation was built Five Points, the United States' first

slum. Five Points was occupied by successive waves of freed slaves,

Irish, then Italian, then Chinese, immigrants. It housed the poor, rural

people leaving farms for opportunity, and the persecuted people from

Europe pouring into New York City. Bars, bordellos, squalid and

lightless tenements lined its streets. Violence and crime were

commonplace. Politicians and social elite discussed it with derision.

Slums like Five Points triggered discussions of affordable housing and

slum removal. As of the start of the 21st century, Five Points slum had

been transformed into the Little Italy and Chinatown neighborhoods of New York City, through that city's campaign of massive urban renewal.

Five Points was not the only slum in America. Jacob Riis, Walker Evans, Lewis Hine

and others photographed many before World War II. Slums were found in

every major urban region of the United States throughout most of the

20th century, long after the Great Depression. Most of these slums had

been ignored by the cities and states which encompassed them until the

1960s' War on Poverty was undertaken by the Federal government of the United States.

A type of slum housing, sometimes called poorhouses, crowded the Boston Commons, later at the fringes of the city.

A 1913 slum dwelling midst squalor in Ivry-sur-Seine, a French commune about 5 kilometers from center of Paris. Slums were scattered around Paris through the 1950s. After Loi Vivien

was passed in July 1970, France demolished some of its last major

bidonvilles (slums) and resettled resident Algerian, Portuguese and

other migrant workers by the mid-1970s.

Rio de Janeiro documented its first slum in 1920 census. By the 1960s, over 33% of population of Rio lived in slums, 45% of Mexico City and Ankara, 65% of Algiers, 35% of Caracas, 25% of Lima and Santiago, 15% of Singapore. By 1980, in various cities and towns of Latin America alone, there were about 25,000 slums.

Causes that create and expand slums

Slums

sprout and continue for a combination of demographic, social, economic,

and political reasons. Common causes include rapid rural-to-urban

migration, poor planning, economic stagnation and depression, poverty,

high unemployment, informal economy, colonialism and segregation,

politics, natural disasters and social conflicts.

Rural–urban migration

Rural–urban migration is one of the causes attributed to the formation and expansion of slums. Since 1950, world population has increased at a far greater rate than the total amount of arable land, even as agriculture

contributes a much smaller percentage of the total economy. For

example, in India, agriculture accounted for 52% of its GDP in 1954 and

only 19% in 2004; in Brazil, the 2050 GDP contribution of agriculture is one-fifth of its contribution in 1951.

Agriculture, meanwhile, has also become higher yielding, less disease

prone, less physically harsh and more efficient with tractors and other

equipment. The proportion of people working in agriculture has declined

by 30% over the last 50 years, while global population has increased by

250%.

Many people move to urban areas

primarily because cities promise more jobs, better schools for poor's

children, and diverse income opportunities than subsistence farming in rural areas. For example, in 1995, 95.8% of migrants to Surabaya, Indonesia reported that jobs were their primary motivation for moving to the city.

However, some rural migrants may not find jobs immediately because of

their lack of skills and the increasingly competitive job markets, which

leads to their financial shortage. Many cities, on the other hand, do not provide enough low-cost housing for a large number of rural-urban migrant workers. Some rural–urban migrant workers cannot afford housing in cities and eventually settle down in only affordable slums.

Further, rural migrants, mainly lured by higher incomes, continue to

flood into cities. They thus expand the existing urban slums.

According to Ali and Toran, social networks

might also explain rural–urban migration and people's ultimate

settlement in slums. In addition to migration for jobs, a portion of

people migrate to cities because of their connection with relatives or

families. Once their family support in urban areas is in slums, those

rural migrants intend to live with them in slums

Urbanization

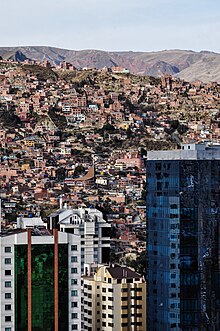

A slum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Rocinha favela is next to skyscrapers and wealthier parts of the city, a

location that provides jobs and easy commute to those who live in the

slums.

The formation of slums is closely linked to urbanization.

In 2008, more than 50% of the world's population lived in urban areas.

In China, for example, it is estimated that the population living in

urban areas will increase by 10% within a decade according to its

current rates of urbanization. The UN-Habitat reports that 43% of urban population in developing countries and 78% of those in the least developed countries are slum dwellers.

Some scholars suggest that urbanization creates slums because local governments are unable to manage urbanization, and migrant workers without an affordable place to live in, dwell in slums. Rapid urbanization drives economic growth and causes people to seek working and investment opportunities in urban areas. However, as evidenced by poor urban infrastructure and insufficient housing, the local governments sometimes are unable to manage this transition.

This incapacity can be attributed to insufficient funds and

inexperience to handle and organize problems brought by migration and

urbanization. In some cases, local governments ignore the flux of immigrants during the process of urbanization. Such examples can be found in many African

countries. In the early 1950s, many African governments believed that

slums would finally disappear with economic growth in urban areas. They

neglected rapidly spreading slums due to increased rural-urban migration

caused by urbanization. Some governments, moreover, mapped the land where slums occupied as undeveloped land.

Another type of urbanization does not involve economic growth but economic stagnation or low growth, mainly contributing to slum growth in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia. This type of urbanization involves a high rate of unemployment, insufficient financial resources and inconsistent urban planning policy. In these areas, an increase of 1% in urban population will result in an increase of 1.84% in slum prevalence.

Urbanization might also force some people to live in slums when it influences land use

by transforming agricultural land into urban areas and increases land

value. During the process of urbanization, some agricultural land is

used for additional urban activities. More investment will come into

these areas, which increases the land value.

Before some land is completely urbanized, there is a period when the

land can be used for neither urban activities nor agriculture. The

income from the land will decline, which decreases the people's incomes

in that area. The gap between people's low income and the high land

price forces some people to look for and construct cheap informal settlements, which are known as slums in urban areas. The transformation of agricultural land also provides surplus labor, as peasants have to seek jobs in urban areas as rural-urban migrant workers.

Many slums are part of economies of agglomeration in which there is an emergence of economies of scale at the firm level, transport costs and the mobility of the industrial labour force. The increase in returns of scale will mean that the production of each good will take place in a single location.

And even though an agglomerated economy benefits these cities by

bringing in specialization and multiple competing suppliers, the

conditions of slums continue to lag behind in terms of quality and

adequate housing. Alonso-Villar argues that the existence of transport

costs implies that the best locations for a firm will be those with easy

access to markets, and the best locations for workers, those with easy

access to goods. The concentration is the result of a self-reinforcing

process of agglomeration.

Concentration is a common trend of the distribution of population.

Urban growth is dramatically intense in the less developed countries,

where a large number of huge cities have started to appear; which means

high poverty rates, crime, pollution and congestion.

Poor house planning

Lack of affordable low cost housing and poor planning encourages the supply side of slums.

The Millennium Development Goals proposes that member nations should

make a "significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million

slum dwellers" by 2020.

If member nations succeed in achieving this goal, 90% of the world

total slum dwellers may remain in the poorly housed settlements by 2020. Choguill claims that the large number of slum dwellers indicates a deficiency of practical housing policy.

Whenever there is a significant gap in growing demand for housing and

insufficient supply of affordable housing, this gap is typically met in

part by slums. The Economist summarizes this as, "good housing is obviously better than a slum, but a slum is better than none".

Insufficient financial resources and lack of coordination in government bureaucracy are two main causes of poor house planning. Financial deficiency in some governments may explain the lack of affordable public housing for the poor since any improvement of the tenant in slums and expansion of public housing programs involve a great increase in the government expenditure. The problem can also lie on the failure in coordination among different departments in charge of economic development, urban planning, and land allocation. In some cities, governments assume that the housing market

will adjust the supply of housing with a change in demand. However,

with little economic incentive, the housing market is more likely to

develop middle-income housing rather than low-cost housing. The urban

poor gradually become marginalized in the housing market where few

houses are built to sell to them.

Colonialism and segregation

An integrated slum dwelling and informal economy inside Dharavi of Mumbai.

Dharavi slum started in 1887 with industrial and segregationist

policies of the British colonial era. The slum housing, tanneries,

pottery and other economy established inside and around Dharavi during

the British rule of India.

Some of the slums in today's world are a product of urbanization brought by colonialism. For instance, the Europeans arrived in Kenya in the nineteenth century and created urban centers such as Nairobi mainly to serve their financial interests. They regarded the Africans as temporary migrants and needed them only for supply of labor.

The housing policy aiming to accommodate these workers was not well

enforced and the government built settlements in the form of

single-occupancy bedspaces. Due to the cost of time and money in their

movement back and forth between rural and urban areas, their families

gradually migrated to the urban centre. As they could not afford to buy

houses, slums were thus formed.

Others were created because of segregation imposed by the colonialists. For example, Dharavi slum of Mumbai – now one of the largest slums in India,

used to be a village referred to as Koliwadas, and Mumbai used to be

referred as Bombay. In 1887, the British colonial government expelled

all tanneries, other noxious industry and poor natives who worked in the

peninsular part of the city and colonial housing area, to what was back

then the northern fringe of the city – a settlement now called Dharavi.

This settlement attracted no colonial supervision or investment in

terms of road infrastructure, sanitation,

public services or housing. The poor moved into Dharavi, found work as

servants in colonial offices and homes and in the foreign owned

tanneries and other polluting industries near Dharavi. To live, the poor

built shanty towns within easy commute to work. By 1947, the year India

became an independent nation of the commonwealth, Dharavi had blossomed

into Bombay's largest slum.

Similarly, some of the slums of Lagos, Nigeria sprouted because of neglect and policies of the colonial era. During apartheid era of South Africa,

under the pretext of sanitation and plague epidemic prevention, racial

and ethnic group segregation was pursued, people of color were moved to

the fringes of the city, policies that created Soweto and other slums –

officially called townships. Large slums started at the fringes of segregation-conscious colonial city centers of Latin America. Marcuse suggests ghettoes in the United States, and elsewhere, have been created and maintained by the segregationist policies of the state and regionally dominant group.

Makoko – One of the oldest slums in Nigeria, was originally a fishing village settlement, built on stilts on a lagoon. It developed into a slum and became home to about a hundred thousand people in Lagos.

In 2012, it was destroyed by the city government, amidst controversy,

to accommodate infrastructure for the city's growing population.

Poor infrastructure, social exclusion and economic stagnation

Social exclusion and poor infrastructure forces the poor to adapt to

conditions beyond his or her control. Poor families that cannot afford

transportation, or those who simply lack any form of affordable public

transportation, generally end up in squat settlements within walking

distance or close enough to the place of their formal or informal

employment. Ben Arimah cites this social exclusion and poor infrastructure as a cause for numerous slums in African cities.

Poor quality, unpaved streets encourage slums; a 1% increase in paved

all-season roads, claims Arimah, reduces slum incidence rate by about

0.35%. Affordable public transport and economic infrastructure empowers

poor people to move and consider housing options other than their

current slums.

A growing economy that creates jobs at rate faster than

population growth, offers people opportunities and incentive to relocate

from poor slum to more developed neighborhoods. Economic stagnation, in

contrast, creates uncertainties and risks for the poor, encouraging

people to stay in the slums. Economic stagnation in a nation with a

growing population reduces per capita disposal income in urban and rural

areas, increasing urban and rural poverty. Rising rural poverty also

encourages migration to urban areas. A poorly performing economy, in

other words, increases poverty and rural-to-urban migration, thereby

increasing slums.

Informal economy

Many

slums grow because of growing informal economy which creates demand

for workers. Informal economy is that part of an economy that is neither

registered as a business nor licensed, one that does not pay taxes and

is not monitored by local or state or federal government.

Informal economy grows faster than formal economy when government laws

and regulations are opaque and excessive, government bureaucracy is

corrupt and abusive of entrepreneurs, labor laws are inflexible, or when

law enforcement is poor.

Urban informal sector is between 20 and 60% of most developing

economies' GDP; in Kenya, 78 per cent of non-agricultural employment is

in the informal sector making up 42 per cent of GDP.

In many cities the informal sector accounts for as much as 60 per cent

of employment of the urban population. For example, in Benin, slum

dwellers comprise 75 per cent of informal sector workers, while in

Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, Chad and Ethiopia, they make

up 90 per cent of the informal labour force.

Slums thus create an informal alternate economic ecosystem, that

demands low paid flexible workers, something impoverished residents of

slums deliver. In other words, countries where starting, registering and

running a formal business is difficult, tend to encourage informal

businesses and slums. Without a sustainable formal economy that raise incomes and create opportunities, squalid slums are likely to continue.

A slum near Ramos Arizpe in Mexico.

The World Bank and UN Habitat estimate, assuming no major economic

reforms are undertaken, more than 80% of additional jobs in urban areas

of developing world may be low-paying jobs in the informal sector.

Everything else remaining same, this explosive growth in the informal

sector is likely to be accompanied by a rapid growth of slums.

Poverty

Urban poverty encourages the formation and demand for slums.

With rapid shift from rural to urban life, poverty migrates to urban

areas. The urban poor arrives with hope, and very little of anything

else. He or she typically has no access to shelter, basic urban services

and social amenities. Slums are often the only option for the urban

poor.

A woman from a slum is taking a bath in a river.

Politics

Many

local and national governments have, for political interests, subverted

efforts to remove, reduce or upgrade slums into better housing options

for the poor.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, for example, French

political parties relied on votes from slum population and had vested

interests in maintaining that voting block. Removal and replacement of

slum created a conflict of interest, and politics prevented efforts to

remove, relocate or upgrade the slums into housing projects that are

better than the slums. Similar dynamics are cited in favelas of Brazil, slums of India, and shanty towns of Kenya.

The

location of 30 largest "contiguous" mega-slums in the world. Numerous

other regions have slums, but those slums are scattered. The numbers

show population in millions per mega-slum, the initials are derived from

city name. Some of the largest slums of the world are in areas of

political or social conflicts.

Scholars

claim politics also drives rural-urban migration and subsequent

settlement patterns. Pre-existing patronage networks, sometimes in the

form of gangs and other times in the form of political parties or social

activists, inside slums seek to maintain their economic, social and

political power. These social and political groups have vested interests

to encourage migration by ethnic groups that will help maintain the

slums, and reject alternate housing options even if the alternate

options are better in every aspect than the slums they seek to replace.

Social conflicts

Millions of Lebanese people formed slums during the civil war from 1975 to 1990. Similarly, in recent years, numerous slums have sprung around Kabul to accommodate rural Afghans escaping Taliban violence.

Natural disasters

Major

natural disasters in poor nations often lead to migration of

disaster-affected families from areas crippled by the disaster to

unaffected areas, the creation of temporary tent city and slums, or

expansion of existing slums.

These slums tend to become permanent because the residents do not want

to leave, as in the case of slums near Port-au-Prince after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and slums near Dhaka after 2007 Bangladesh Cyclone Sidr.

Characteristics of slums

Location and growth

Slums

typically begin at the outskirts of a city. Over time, the city may

expand past the original slums, enclosing the slums inside the urban

perimeter. New slums sprout at the new boundaries of the expanding city,

usually on publicly owned lands, thereby creating an urban sprawl mix

of formal settlements, industry, retail zones and slums. This makes the

original slums valuable property, densely populated with many

conveniences attractive to the poor.

At their start, slums are typically located in least desirable

lands near the town or city, that are state owned or philanthropic trust

owned or religious entity owned or have no clear land title. In cities

located over a mountainous terrain, slums begin on difficult to reach

slopes or start at the bottom of flood prone valleys, often hidden from

plain view of city center but close to some natural water source.

In cities located near lagoons, marshlands and rivers, they start at

banks or on stilts above water or the dry river bed; in flat terrain,

slums begin on lands unsuitable for agriculture, near city trash dumps,

next to railway tracks, and other shunned undesirable locations.

These strategies shield slums from the risk of being noticed and

removed when they are small and most vulnerable to local government

officials. Initial homes tend to be tents and shacks that are quick to

install, but as slum grows, becomes established and newcomers pay the

informal association or gang for the right to live in the slum, the

construction materials for the slums switches to more lasting materials

such as bricks and concrete, suitable for slum's topography.

The original slums, over time, get established next to centers of

economic activity, schools, hospitals, sources of employment, which the

poor rely on. Established old slums, surrounded by the formal city

infrastructure, cannot expand horizontally; therefore, they grow

vertically by stacking additional rooms, sometimes for a growing family

and sometimes as a source of rent from new arrivals in slums.

Some slums name themselves after founders of political parties, locally

respected historical figures, current politicians or politician's

spouse to garner political backing against eviction.

Insecure tenure

Informality of land tenure is a key characteristic of urban slums.

At their start, slums are typically located in least desirable lands

near the town or city, that are state owned or philanthropic trust owned

or religious entity owned or have no clear land title. Some immigrants regard unoccupied land as land without owners and therefore occupy it.

In some cases the local community or the government allots lands to

people, which will later develop into slums and over which the dwellers

don't have property rights. Informal land tenure also includes occupation of land belonging to someone else. According to Flood, 51 percent of slums are based on invasion to private land in sub-Saharan Africa, 39 percent in North Africa and West Asia, 10 percent in South Asia, 40 percent in East Asia, and 40 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In some cases, once the slum has many residents, the early residents

form a social group, an informal association or a gang that controls

newcomers, charges a fee for the right to live in the slums, and

dictates where and how new homes get built within the slum. The

newcomers, having paid for the right, feel they have commercial right to

the home in that slum.

The slum dwellings, built earlier or in later period as the slum grows,

are constructed without checking land ownership rights or building

codes, are not registered with the city, and often not recognized by the

city or state governments.

Secure land tenure is important for slum dwellers as an authentic

recognition of their residential status in urban areas. It also

encourages them to upgrade their housing facilities, which will give

them protection against natural and unnatural hazards. Undocumented ownership with no legal title to the land also prevents slum settlers from applying for mortgage,

which might worsen their financial situations. In addition, without

registration of the land ownership, the government has difficulty in

upgrading basic facilities and improving the living environment.

Insecure tenure of the slum, as well as lack of socially and

politically acceptable alternatives to slums, also creates difficulty in

citywide infrastructure development such as rapid mass transit, electrical line and sewer pipe layout, highways and roads.

Substandard housing and overcrowding

Slum areas are characterized by substandard housing structures.

Shanty homes are often built hurriedly, on ad hoc basis, with materials

unsuitable for housing. Often the construction quality is inadequate to

withstand heavy rains, high winds, or other local climate and location.

Paper, plastic, earthen floors, mud-and-wattle walls, wood held

together by ropes, straw or torn metal pieces as roofs are some of the

materials of construction. In some cases, brick and cement is used, but

without attention to proper design and structural engineering

requirements. Various space, dwelling placement bylaws and local building codes may also be extensively violated.

Overcrowding is another characteristic of slums. Many dwellings

are single room units, with high occupancy rates. Each dwelling may be

cohabited by multiple families. Five and more persons may share a

one-room unit; the room is used for cooking, sleeping and living.

Overcrowding is also seen near sources of drinking water, cleaning, and

sanitation where one toilet may serve dozens of families. In a slum of Kolkata, India, over 10 people sometimes share a 45 m2 room.

In Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya, population density is estimated at

2,000 people per hectare — or about 500,000 people in one square mile.

However, the density and neighbourhood effects of slum populations may also offer an opportunity to target health interventions.

Inadequate or no infrastructure

Slum with tiled roofs and railway, Jakarta railway slum resettlement 1975, Indonesia.

One of the identifying characteristics of slums is the lack of or inadequate public infrastructure.

From safe drinking water to electricity, from basic health care to

police services, from affordable public transport to fire/ambulance

services, from sanitation sewer to paved roads, new slums usually lack

all of these. Established, old slums sometimes garner official support

and get some of these infrastructure such as paved roads and unreliable

electricity or water supply.

Slums often have very narrow alleys that do not allow vehicles (including emergency vehicles) to pass. The lack of services such as routine garbage collection allows rubbish to accumulate in huge quantities.

The lack of infrastructure is caused by the informal nature of

settlement and no planning for the poor by government officials. Fires

are often a serious problem.

In many countries, local and national government often refuse to

recognize slums, because the slum are on disputed land, or because of

the fear that quick official recognition will encourage more slum

formation and seizure of land illegally. Recognizing and notifying slums

often triggers a creation of property rights, and requires that the

government provide public services and infrastructure to the slum

residents.

With poverty and informal economy, slums do not generate tax revenues

for the government and therefore tend to get minimal or slow attention.

In other cases, the narrow and haphazard layout of slum streets, houses

and substandard shacks, along with persistent threat of crime and

violence against infrastructure workers, makes it difficult to layout

reliable, safe, cost effective and efficient infrastructure. In yet

others, the demand far exceeds the government bureaucracy's ability to

deliver.

Low socioeconomic status of its residents is another common characteristic attributed to slum residents.

Problems

Vulnerability to natural and unnatural hazards

Slums in the city of Chau Doc, Vietnam over river Hậu (Mekong branch). These slums are on stilts to withstand routine floods which last 3 to 4 months every year.

Slums are often placed among the places vulnerable to natural disasters such as landslides and floods.

In cities located over a mountainous terrain, slums begin on slopes

difficult to reach or start at the bottom of flood prone valleys, often

hidden from plain view of city center but close to some natural water

source. In cities located near lagoons, marshlands

and rivers, they start at banks or on stilts above water or the dry

river bed; in flat terrain, slums begin on lands unsuitable for

agriculture, near city trash dumps, next to railway tracks,

and other shunned, undesirable locations. These strategies shield slums

from the risk of being noticed and removed when they are small and most

vulnerable to local government officials.

However, the ad hoc construction, lack of quality control on building

materials used, poor maintenance, and uncoordinated spatial design make

them prone to extensive damage during earthquakes as well from decay. These risks will be intensified by climate change.

A slum in Haiti

damaged by 2010 earthquake. Slums are vulnerable to extensive damage

and human fatalities from landslides, floods, earthquakes, fire, high

winds and other severe weather.

Some slums risk man-made hazards such as toxic industries, traffic congestion and collapsing infrastructure. Fires are another major risk to slums and its inhabitants, with streets too narrow to allow proper and quick access to fire control trucks.

Unemployment and informal economy

Due to lack of skills and education as well as competitive job markets, many slum dwellers face high rates of unemployment. The limit of job opportunities causes many of them to employ themselves in the informal economy,

inside the slum or in developed urban areas near the slum. This can

sometimes be licit informal economy or illicit informal economy without

working contract or any social security. Some of them are seeking jobs

at the same time and some of those will eventually find jobs in formal

economies after gaining some professional skills in informal sectors.

Examples of licit informal economy include street vending,

household enterprises, product assembly and packaging, making garlands

and embroideries, domestic work, shoe polishing or repair, driving tuk-tuk or manual rickshaws, construction workers or manually driven logistics, and handicrafts production.

In some slums, people sort and recycle trash of different kinds (from

household garbage to electronics) for a living – selling either the odd

usable goods or stripping broken goods for parts or raw materials.

Typically these licit informal economies require the poor to regularly

pay a bribe to local police and government officials.

A

propaganda poster linking slum to violence, used by US Housing

Authority in the 1940s. City governments in the USA created many such

propaganda posters and launched a media campaign to gain citizen support

for slum clearance and planned public housing.

Examples of illicit informal economy include illegal substance and weapons trafficking, drug or moonshine/changaa production, prostitution and gambling – all sources of risks to the individual, families and society. Recent reports reflecting illicit informal economies include drug trade and distribution in Brazil's favelas, production of fake goods in the colonías of Tijuana, smuggling in katchi abadis and slums of Karachi, or production of synthetic drugs in the townships of Johannesburg.

The slum-dwellers in informal economies run many risks. The

informal sector, by its very nature, means income insecurity and lack of

social mobility. There is also absence of legal contracts, protection

of labor rights, regulations and bargaining power in informal

employments.

Violence

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong was controlled by local triads.

Some scholars suggest that crime is one of the main concerns in slums.

Empirical data suggest crime rates are higher in some slums than in

non-slums, with slum homicides alone reducing life expectancy of a

resident in a Brazil slum by 7 years than for a resident in nearby

non-slum. In some countries like Venezuela, officials have sent in the military to control slum criminal violence involved with drugs and weapons. Rape

is another serious issue related to crime in slums. In Nairobi slums,

for example, one fourth of all teenage girls are raped each year.

On the other hand, while UN-Habitat reports some slums are more exposed to crimes

with higher crime rates (for instance, the traditional inner-city

slums), crime is not the direct resultant of block layout in many slums.

Rather crime is one of the symptoms of slum dwelling; thus slums

consist of more victims than criminals.

Consequently, slums in all do not have consistently high crime rates;

slums have the worst crime rates in sectors maintaining influence of

illicit economy – such as drug trafficking, brewing, prostitution and gambling –. Often in such circumstance, multiple gangs fight for control over revenue.

Slum crime rate correlates with insufficient law enforcement and inadequate public policing.

In main cities of developing countries, law enforcement lags behind

urban growth and slum expansion. Often police can not reduce crime

because, due to ineffective city planning and governance, slums set

inefficient crime prevention system. Such problems is not primarily due

to community indifference. Leads and information intelligence from slums

are rare, streets are narrow and a potential death traps to patrol, and

many in the slum community have an inherent distrust of authorities

from fear ranging from eviction to collection on unpaid utility bills to

general law and order. Lack of formal recognition by the governments also leads to few formal policing and public justice institutions in slums.

Women in slums are at greater risk of physical and sexual violence.

Factors such as unemployment that lead to insufficient resources in the

household can increase marital stress and therefore exacerbate domestic

violence.

Slums are often non-secured areas and women often risk sexual violence when they walk alone in slums late at night. Violence against women and women's security in slums emerge as recurrent issues.

Another prevalent form of violence in slums is armed violence (gun violence), mostly existing in African and Latin American slums. It leads to homicide and the emergence of criminal gangs. Typical victims are male slum residents. Violence often leads to retaliatory and vigilante violence within the slum. Gang and drug wars are endemic in some slums, predominantly between male residents of slums.

The police sometimes participate in gender-based violence against men

as well by picking up some men, beating them and putting them in jail. Domestic violence against men also exists in slums, including verbal abuses and even physical violence from households.

Cohen as well as Merton theorized that the cycle of slum violence

does not mean slums are inevitably criminogenic, rather in some cases

it is frustration against life in slum, and a consequence of denial of

opportunity to slum residents to leave the slum.

Further, crime rates are not uniformly high in world's slums; the

highest crime rates in slums are seen where illicit economy – such as

drug trafficking, brewing, prostitution and gambling – is strong and

multiple gangs are fighting for control.

A young boy sits over an open sewer in the Kibera slum, Nairobi.

Infectious Diseases and Epidemics

Slum dwellers usually experience a high rate of disease. Diseases that have been reported in slums include cholera, HIV/AIDS, measles, malaria, dengue, typhoid, drug resistant tuberculosis, and other epidemics. Studies focus on children's health in slums address that cholera and diarrhea are especially common among young children. Besides children's vulnerability to diseases, many scholars also focus on high HIV/AIDS prevalence in slums among women. Throughout slum areas in various parts of the world, infectious diseases are a significant contributor to high mortality rates.

For example, according to a study in Nairobi's slums, HIV/AIDS and

tuberculosis attributed to about 50% of the mortality burden.

Factors that have been attributed to a higher rate of disease transmission in slums include high population densities, poor living conditions, low vaccination rates, insufficient health-related data and inadequate health service. Overcrowding leads to faster and wider spread of diseases due to the limited space in slum housing. Poor living conditions also make slum dwellers more vulnerable to certain diseases. Poor water quality, a manifest example, is a cause of many major illnesses including malaria, diarrhea and trachoma.

Improving living conditions such as introduction of better sanitation

and access to basic facilities can ameliorate the effects of diseases,

such as cholera.

Slums have been historically linked to epidemics, and this trend has continued in modern times. For example, the slums of West African nations such as Liberia were crippled by as well as contributed to the outbreak and spread of Ebola in 2014. Slums are considered a major public health

concern and potential breeding grounds of drug resistant diseases for

the entire city, the nation, as well as the global community.

Child malnutrition

Child malnutrition is more common in slums than in non-slum areas.

In Mumbai and New Delhi,

47% and 51% of slum children under the age of five are stunted and 35%

and 36% of them are underweighted. These children all suffer from

third-degree malnutrition, the most severe level, according to WHO standards. A study conducted by Tada et al. in Bangkok

slums illustrates that in terms of weight-forage, 25.4% of the children

who participated in the survey suffered from malnutrition, compared to

around 8% national malnutrition prevalence in Thailand. In Ethiopia and the Niger, rates of child malnutrition in urban slums are around 40%.

The major nutritional problems in slums are protein-energy malnutrition (PEM), vitamin A deficiency (VAD), iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and iodine deficiency disorders (IDD). Malnutrition can sometimes lead to death among children. Dr. Abhay Bang's report shows that malnutrition kills 56,000 children annually in urban slums in India.

Widespread child malnutrition in slums is closely related to family income, mothers' food practice, mothers' educational level, and maternal employment or housewifery. Poverty may result in inadequate food intake when people cannot afford to buy and store enough food, which leads to malnutrition. Another common cause is mothers' faulty feeding practices, including inadequate breastfeeding and wrongly preparation of food for children. Tada et al.'s study in Bangkok slums shows that around 64% of the mothers sometimes fed their children instant food

instead of a normal meal. And about 70% of the mothers did not provide

their children three meals everyday. Mothers' lack of education leads to

their faulty feeding practices. Many mothers in slums don't have

knowledge on food nutrition for children.

Maternal employment also influences children's nutritional status. For

the mothers who work outside, their children are prone to be

malnourished. These children are likely to be neglected by their mothers

or sometimes not carefully looked after by their female relatives. Recent study has shown improvements in health awareness in adolescent age group of a rural slum area.

Other Non-communicable Diseases

A

multitude of non-contagious diseases also impact health for slum

residents. Examples of prevalent non-infectious diseases include:

cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease,

neurological disorders, and mental illness.

In some slum areas of India, diarrhea is a significant health problem

among children. Factors like poor sanitation, low literacy rates, and

limited awareness make diarrhea and other dangerous diseases extremely

prevalent and burdensome on the community.

Lack of reliable data also has a negative impact on slum

dwellers' health. A number of slum families do not report cases or seek

professional medical care, which results in insufficient data.

This might prevent appropriate allocation of health care resources in

slum areas since many countries base their health care plans on data

from clinic, hospital, or national mortality registry. Moreover, health service is insufficient or inadequate in most of the world's slums. Emergency ambulance service and urgent care services are typically unavailable, as health service providers sometimes avoid servicing slums. A study shows that more than half of slum dwellers are prone to visit private practitioners or seek self-medication with medicines available in the home.

Private practitioners in slums are usually those who are unlicensed or

poorly trained and they run clinics and pharmacies mainly for the sake

of money.

The categorization of slum health by the government and census data

also has an effect on the distribution and allocation of health

resources in inner city areas. A significant portion of city populations

face challenges with access to health care but do not live in locations

that are described as within the "slum" area.

Overall, a complex network of physical, social, and environmental

factors contribute to the health threats faced by slum residents.

Countermeasures

Villa 31, one of the largest slums of Argentina, located near the center of Buenos Aires

Recent years have seen a dramatic growth in the number of slums as urban populations have increased in developing countries.

Nearly a billion people worldwide live in slums, and some project the

figure may grow to 2 billion by 2030, if governments and global

community ignore slums and continue current urban policies. United

Nations Habitat group believes change is possible. To achieve the goal

of "cities without slums", the UN claims that governments must undertake

vigorous urban planning, city management, infrastructure development,

slum upgrading and poverty reduction.

Slum removal

Some city and state officials have simply sought to remove slums.

This strategy for dealing with slums is rooted in the fact that slums

typically start illegally on someone else's land property, and they are

not recognized by the state. As the slum started by violating another's

property rights, the residents have no legal claim to the land.

Critics argue that slum removal by force tend to ignore the

social problems that cause slums. The poor children as well as working

adults of a city's informal economy need a place to live. Slum clearance

removes the slum, but it does not remove the causes that create and

maintain the slum.

Slum relocation

Slum

relocation strategies rely on removing the slums and relocating the

slum poor to free semi-rural peripheries of cities, sometimes in free

housing. This strategy ignores several dimensions of a slum life. The

strategy sees slum as merely a place where the poor lives. In reality,

slums are often integrated with every aspect of a slum resident's life,

including sources of employment, distance from work and social life. Slum relocation that displaces the poor from opportunities to earn a livelihood, generates economic insecurity in the poor.

In some cases, the slum residents oppose relocation even if the

replacement land and housing to the outskirts of cities is free and of

better quality than their current house. Examples include Zone One Tondo

Organization of Manila, Philippines and Abahlali baseMjondolo of Durban, South Africa. In other cases, such as Ennakhil slum relocation project in Morocco,

systematic social mediation has worked. The slum residents have been

convinced that their current location is a health hazard, prone to

natural disaster, or that the alternative location is well connected to

employment opportunities.

Slum Upgrading

Some governments have begun to approach slums as a possible

opportunity to urban development by slum upgrading. This approach was

inspired in part by the theoretical writings of John Turner in 1972. The approach seeks to upgrade the slum with basic infrastructure such as sanitation, safe drinking water, safe electricity distribution, paved roads, rain water drainage system, and bus/metro stops.

The assumption behind this approach is that if slums are given basic

services and tenure security – that is, the slum will not be destroyed

and slum residents will not be evicted, then the residents will rebuild

their own housing, engage their slum community to live better, and over

time attract investment from government organizations and businesses.

Turner argued to demolish the housing, but to improve the environment:

if governments can clear existing slums of unsanitary human waste,

polluted water and litter, and from muddy unlit lanes, they do not have

to worry about the shanty housing. "Squatters"

have shown great organizational skills in terms of land management, and

they will maintain the infrastructure that is provided.

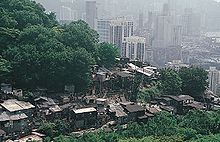

Shibati slum in Chongqing, China. This slum is being demolished and residents relocated.

In Mexico City

for example, the government attempted to upgrade and urbanize settled

slums in the periphery during the 1970s and 1980s by including basic

amenities such as concrete roads, parks, illumination and sewage.

Currently, most slums in Mexico City face basic characteristics of

traditional slums, characterized to some extent in housing, population

density, crime and poverty, however, the vast majority of its

inhabitants have access to basic amenities and most areas are connected

to major roads and completely urbanized. Nevertheless, smaller

settlements lacking these can still be found in the periphery of the

city and its inhabitants are known as "paracaidistas".

Another example of this approach is the slum upgrade in Tondo slum near Manila, Philippines.

The project was anticipated to be complete in four years, but it took

nine. There was a large increase in cost, numerous delays,

re-engineering of details to address political disputes, and other

complications after the project. Despite these failures, the project

reaffirmed the core assumption and Tondo families did build their own

houses of far better quality than originally assumed. Tondo residents

became property owners with a stake in their neighborhood. A more recent

example of slum-upgrading approach is PRIMED initiative in Medellin, Colombia, where streets, Metrocable

transportation and other public infrastructure has been added. These

slum infrastructure upgrades were combined with city infrastructure

upgrade such as addition of metro, paved roads and highways to empower

all city residents including the poor with reliable access throughout

city.

Most slum upgrading projects, however, have produced mixed

results. While initial evaluations were promising and success stories

widely reported by media, evaluations done 5 to 10 years after a project

completion have been disappointing. Herbert Werlin notes that the initial benefits of slum upgrading efforts have been ephemeral. The slum upgrading projects in kampungs

of Jakarta Indonesia, for example, looked promising in first few years

after upgrade, but thereafter returned to a condition worse than before,

particularly in terms of sanitation, environmental problems and safety

of drinking water. Communal toilets provided under slum upgrading effort

were poorly maintained, and abandoned by slum residents of Jakarta. Similarly slum upgrading efforts in Philippines, India, and Brazil

have proven to be excessively more expensive than initially estimated,

and the condition of the slums 10 years after completion of slum

upgrading has been slum like. The anticipated benefits of slum

upgrading, claims Werlin, have proven to be a myth.

A slum dwelling in Borgergade in central Copenhagen Denmark,

about 1940. The Danish government passed The Slum Clearance Act in

1939, demolished many slums including Borgergade, replacing it with

modern buildings by the early 1950s.

Slum upgrading is largely a government controlled, funded and run

process, rather than a competitive market driven process. Krueckeberg

and Paulsen note

conflicting politics, government corruption and street violence in slum

regularization process is part of the reality. Slum upgrading and

tenure regularization also upgrade and regularize the slum bosses and

political agendas, while threatening the influence and power of

municipal officials and ministries. Slum upgrading does not address

poverty, low paying jobs from informal economy, and other

characteristics of slums. It is unclear whether slum upgrading can lead

to long term sustainable improvement to slums.

Urban infrastructure development and public housing

Urban infrastructure such as reliable high speed mass transit system,

motorways/interstates, and public housing projects have been cited as responsible for the disappearance of major slums in the United States and Europe from the 1960s through 1970s. Charles Pearson

argued in UK Parliament that mass transit would enable London to reduce

slums and relocate slum dwellers. His proposal was initially rejected

for lack of land and other reasons; but Pearson and others persisted

with creative proposals such as building the mass transit under the

major roads already in use and owned by the city. London Underground was born, and its expansion has been credited to reducing slums in respective cities (and to an extent, the New York City Subway's smaller expansion).

As cities expanded and business parks scattered due to cost

ineffectiveness, people moved to live in the suburbs; thus retail,

logistics, house maintenance and other businesses followed demand

patterns. City governments used infrastructure investments and urban

planning to distribute work, housing, green areas, retail, schools and

population densities. Affordable public mass transit in cities such as

New York City, London and Paris allowed the poor to reach areas where

they could earn a livelihood. Public and council housing projects

cleared slums and provided more sanitary housing options than what

existed before the 1950s.

Slum clearance became a priority policy in Europe between

1950–1970s, and one of the biggest state-led programs. In the UK, the

slum clearance effort was bigger in scale than the formation of British Railways, the National Health Service

and other state programs. UK Government data suggests the clearances

that took place after 1955 demolished about 1.5 million slum properties,

resettling about 15% of UK's population out of these properties. Similarly, after 1950, Denmark and others pursued parallel initiatives to clear slums and resettle the slum residents.

The US and European governments additionally created a procedure

by which the poor could directly apply to the government for housing

assistance, thus becoming a partner to identifying and meeting the

housing needs of its citizens.

One historically effective approach to reduce and prevent slums has

been citywide infrastructure development combined with affordable,

reliable public mass transport and public housing projects.

In Brazil, in 2014, the government built about 2 million houses

around the country for lower income families. The public program was

named "Minha casa, minha vida" which means "My house, my life". The project has built 2 million popular houses and it has 2 million more under construction.

However, slum relocation in the name of urban development is

criticized for uprooting communities without consultation or

consideration of ongoing livelihood. For example, the Sabarmati

Riverfront Project, a recreational development in Ahmedabad, India,

forcefully relocated over 19,000 families from shacks along the river to

13 public housing complexes that were an average of 9 km away from the

family's original dwelling.

Prevalence

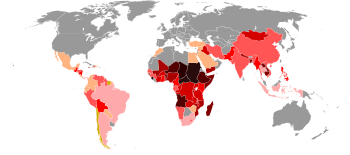

Percent urban population of a country living in slums.

(Source: UN Habitat 2005)

(Source: UN Habitat 2005)

0-10%

10-20%

20-30%

30-40%

40-50%

50-60%

60-70%

70-80%

80-90%

90-100%

No data

Slums exist in many countries and have become a global phenomenon. A UN-Habitat report states that in 2006 there were nearly 1 billion people settling in slum settlements in most cities of Latin America, Asia, and Africa, and a smaller number in the cities of Europe and North America. In 2012, according to UN-Habitat, about 863 million people in the developing world lived in slums. Of these, the urban slum population at mid-year was around 213 million in Sub-Saharan Africa, 207 million in East Asia, 201 million in South Asia, 113 million in Latin America and Caribbean, 80 million in Southeast Asia, 36 million in West Asia, and 13 million in North Africa. Among individual countries, the proportion of urban residents living in slum areas in 2009 was highest in the Central African Republic (95.9%), Chad (89.3%), Niger (81.7%), and Mozambique (80.5%).

The distribution of slums within a city varies throughout the world. In most of the developed countries, it is easier to distinguish the slum-areas and non-slum areas. In the United States, slum dwellers are usually in city neighborhoods and inner suburbs, while in Europe, they are more common in high rise housing on the urban outskirts. In many developing countries, slums are prevalent as distributed pockets or as urban orbits of densely constructed informal settlements. In some cities, especially in countries in Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa,

slums are not just marginalized neighborhoods holding a small

population; slums are widespread, and are home to a large part of urban

population. These are sometimes called slum cities.

The percentage of developing world's urban population living in

slums has been dropping with economic development, even while total

urban population has been increasing. In 1990, 46 percent of the urban

population lived in slums; by 2000, the percentage had dropped to 39%;

which further dropped to 32% by 2010.