In its broadest sense, social vulnerability is one dimension of vulnerability to multiple stressors and shocks, including abuse, social exclusion and natural hazards. Social vulnerability refers to the inability of people, organizations, and societies to withstand adverse impacts from multiple stressors to which they are exposed. These impacts are due in part to characteristics inherent in social interactions, institutions, and systems of cultural values.

Because it is most apparent when calamity occurs, many studies of social vulnerability are found in risk management literature.

Definitions

"Vulnerability" derives from the Latin word vulnerare

(to be wounded) and describes the potential to be harmed physically

and/or psychologically. Vulnerability is often understood as the

counterpart of resilience, and is increasingly studied in linked social-ecological systems. The Yogyakarta Principles, one of the international human rights instruments use the term "vulnerability" as such potential to abuse or social exclusion.

The concept of social vulnerability emerged most recently within

the discourse on natural hazards and disasters. To date no one

definition has been agreed upon. Similarly, multiple theories of social

vulnerability exist.

Most work conducted so far focuses on empirical observation and

conceptual models. Thus, current social vulnerability research is a middle range theory

and represents an attempt to understand the social conditions that

transform a natural hazard (e.g. flood, earthquake, mass movements etc.)

into a social disaster. The concept emphasizes two central themes:

- Both the causes and the phenomenon of disasters are defined by social processes and structures. Thus it is not only a geo- or biophysical hazard, but rather the social context that is taken into account to understand “natural” disasters (Hewitt 1983).

- Although different groups of a society may share a similar exposure to a natural hazard, the hazard has varying consequences for these groups, since they have diverging capacities and abilities to handle the impact of a hazard.

Taking a structuralist view, Hewitt (1997, p143) defines vulnerability as being:

...essentially about the human ecology of endangerment...and is embedded in the social geography of settlements and lands uses, and the space of distribution of influence in communities and political organisation.

this is in contrast to the more socially focused view of Blaikie et al. (1994, p9) who define vulnerability as the:

...set of characteristics of a group or individual in terms of their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard. It involves a combination of factors that determine the degree to which someone's life and livelihood is at risk by a discrete and identifiable event in nature or society.

History of the concept

In

the 1970s the concept of vulnerability was introduced within the

discourse on natural hazards and disaster by O´Keefe, Westgate and

Wisner (O´Keefe, Westgate et al. 1976). In “taking the naturalness out

of natural disasters” these authors insisted that socio-economic

conditions are the causes for natural disasters. The work illustrated by

means of empirical data that the occurrence of disasters increased over

the last 50 years, paralleled by an increasing loss of life. The work

also showed that the greatest losses of life concentrate in

underdeveloped countries, where the authors concluded that vulnerability

is increasing.

Chambers put these empirical findings on a conceptual level and

argued that vulnerability has an external and internal side: People are

exposed to specific natural and social risk. At the same time people

possess different capacities to deal with their exposure by means of

various strategies of action (Chambers 1989). This argument was again

refined by Blaikie, Cannon, Davis and Wisner, who went on to develop the

Pressure and Release Model (PAR) (see below). Watts and Bohle argued

similarly by formalizing the “social space of vulnerability”, which is

constituted by exposure, capacity and potentiality (Watts and Bohle

1993).

Susan Cutter

developed an integrative approach (hazard of place), which tries to

consider both multiple geo- and biophysical hazards on the one hand as

well as social vulnerabilities on the other hand (Cutter, Mitchell et

al. 2000). Recently, Oliver-Smith grasped the nature-culture dichotomy

by focusing both on the cultural construction of the

people-environment-relationship and on the material production of

conditions that define the social vulnerability of people (Oliver-Smith

and Hoffman 2002).

Research on social vulnerability to date has stemmed from a

variety of fields in the natural and social sciences. Each field has

defined the concept differently, manifest in a host of definitions and

approaches (Blaikie, Cannon et al. 1994; Henninger 1998; Frankenberger,

Drinkwater et al. 2000; Alwang, Siegel et al. 2001; Oliver-Smith 2003;

Cannon, Twigg et al. 2005). Yet some common threads run through most of

the available work.

Within society

Although

considerable research attention has examined components of biophysical

vulnerability and the vulnerability of the built environment

(Mileti, 1999), we currently know the least about the social aspects of

vulnerability (Cutter et al., 2003). Socially created vulnerabilities

are largely ignored, mainly due to the difficulty in quantifying them.

Social vulnerability is created through the interaction of social forces

and multiple stressors, and resolved through social (as opposed to

individual) means. While individuals within a socially vulnerable

context may break through the “vicious cycle,” social vulnerability

itself can persist because of structural—i.e. social and

political—influences that reinforce vulnerability.

Social vulnerability is partially the product of social

inequalities—those social factors that influence or shape the

susceptibility of various groups to harm and that also govern their

ability to respond (Cutter et al., 2003). It is, however, important to

note that social vulnerability is not registered by exposure to hazards

alone, but also resides in the sensitivity and resilience of the system

to prepare, cope and recover from such hazards (Turner et al., 2003).

However, it is also important to note, that a focus limited to the

stresses associated with a particular vulnerability analysis is also

insufficient for understanding the impact on and responses of the

affected system or its components (Mileti, 1999; Kaperson et al., 2003;

White & Haas, 1974). These issues are often underlined in attempts

to model the concept (see Models of Social Vulnerability).

Models

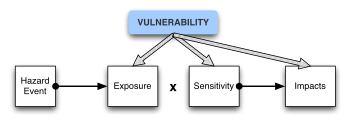

Risk-Hazard

(RH) model (diagram after Turner et al., 2003), showing the impact of a

hazard as a function of exposure and sensitivity. The chain sequence

begins with the hazard, and the concept of vulnerability is noted

implicitly as represented by white arrows.

Two of the principal archetypal reduced-form models of social

vulnerability are presented, that have informed vulnerability analysis:

the Risk-Hazard (RH) model and the Pressure and Release model.

Risk-Hazard (RH) Model

- Initial RH models sought to understand the impact of a hazard as a function of exposure to the hazardous event and the sensitivity of the entity exposed (Turner et al., 2003). Applications of this model in environmental and climate impact assessments generally emphasised exposure and sensitivity to perturbations and stressors (Kates, 1985; Burton et al., 1978) and worked from the hazard to the impacts (Turner et al., 2003). However, several inadequacies became apparent. Principally, it does not treat the ways in which the systems in question amplify or attenuate the impacts of the hazard (Martine & Guzman, 2002). Neither does the model address the distinction among exposed subsystems and components that lead to significant variations in the consequences of the hazards, or the role of political economy in shaping differential exposure and consequences (Blaikie et al., 1994, Hewitt, 1997). This led to the development of the PAR model.

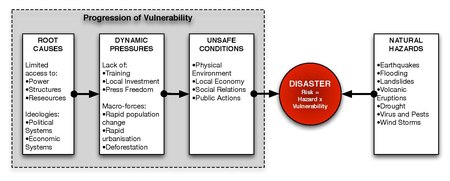

Pressure and Release (PAR) Model

Pressure

and Release (PAR) model after Blaikie et al. (1994) showing the

progression of vulnerability. The diagram shows a disaster as the

intersection between socio-economic pressures on the left and physical

exposures (natural hazards) on the right

- The PAR model understands a disaster as the intersection between socio-economic pressure and physical exposure. Risk is explicitly defined as a function of the perturbation, stressor, or stress and the vulnerability of the exposed unit (Blaikie et al, 1994). In this way, it directs attention to the conditions that make exposure unsafe, leading to vulnerability and to the causes creating these conditions. Used primarily to address social groups facing disaster events, the model emphasises distinctions in vulnerability by different exposure units such as social class and ethnicity. The model distinguishes between three components on the social side: root causes, dynamic pressures and unsafe conditions, and one component on the natural side, the natural hazards itself. Principal root causes include “economic, demographic and political processes”, which affect the allocation and distribution of resources between different groups of people. Dynamic Pressures translate economic and political processes in local circumstances (e.g. migration patterns). Unsafe conditions are the specific forms in which vulnerability is expressed in time and space, such as those induced by the physical environment, local economy or social relations (Blaikie, Cannon et al. 1994).

- Although explicitly highlighting vulnerability, the PAR model appears insufficiently comprehensive for the broader concerns of sustainability science (Turner et al., 2003). Primarily, it does not address the coupled human environment system in the sense of considering the vulnerability of biophysical subsystems (Kasperson et al, 2003) and it provides little detail on the structure of the hazard's causal sequence. The model also tends to underplay feedback beyond the system of analysis that the integrative RH models included (Kates, 1985).

Criticism

Some

authors criticise the conceptualisation of social vulnerability for

overemphasising the social, political and economical processes and

structures that lead to vulnerable conditions. Inherent in such a view

is the tendency to understand people as passive victims (Hewitt 1997)

and to neglect the subjective and intersubjective interpretation and

perception of disastrous events. Bankoff criticises the very basis of

the concept, since in his view it is shaped by a knowledge system that

was developed and formed within the academic environment of western

countries and therefore inevitably represents values and principles of

that culture. According to Bankoff the ultimate aim underlying this

concept is to depict large parts of the world as dangerous and hostile

to provide further justification for interference and intervention

(Bankoff 2003).

Current and future research

Social vulnerability research has become a deeply interdisciplinary

science, rooted in the modern realization that humans are the causal

agents of disasters – i.e., disasters are never natural, but a

consequence of human behavior. The desire to understand geographic,

historic, and socio-economic characteristics of social vulnerability

motivates much of the research being conducted around the world today.

Two principal goals are currently driving the field of social vulnerability research:

- The design of models which explain vulnerability and the root causes which create it, and

- The development of indicators and indexes which attempt to map vulnerability over time and space (Villágran de León 2006).

The temporal and spatial aspects of vulnerability science are

pervasive, particularly in research that attempts to demonstrate the

impact of development on social vulnerability. Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

are increasingly being used to map vulnerability, and to better

understand how various phenomena (hydrological, meteorological,

geophysical, social, political and economic) effect human populations.

Researchers have yet to develop reliable models capable of

predicting future outcomes based upon existing theories and data.

Designing and testing the validity of such models, particularly at the

sub-national scale at which vulnerability reduction takes place, is

expected to become a major component of social vulnerability research in

the future.

An even greater aspiration in social vulnerability research is

the search for one, broadly applicable theory, which can be applied

systematically at a variety of scales, all over the world. Climate

change scientists, building engineers, public health specialists, and

many other related professions have already achieved major strides in

reaching common approaches. Some social vulnerability scientists argue

that it is time for them to do the same, and they are creating a variety

of new forums in order to seek a consensus on common frameworks,

standards, tools, and research priorities. Many academic, policy, and

public/NGO organizations promote a globally applicable approach in

social vulnerability science and policy (see section 5 for links to some

of these institutions).

Disasters often expose pre-existing societal inequalities that

lead to disproportionate loss of property, injury, and death (Wisner,

Blaikie, Cannon, & Davis, 2004). Some disaster researchers argue

that particular groups of people are placed disproportionately at-risk

to hazards. Minorities, immigrants, women, children, the poor, as well

as people with disabilities are among those have been identified as

particularly vulnerable to the impacts of disaster (Cutter et al., 2003;

Peek, 2008; Stough, Sharp, Decker & Wilker, 2010).

Since 2005, the Spanish Red Cross has developed a set of

indicators to measure the multi-dimensional aspects of social

vulnerability. These indicators are generated through the statistical

analysis of more than 500 thousand people who are suffering of economic

strain and social vulnerability, and who have a personal record

containing 220 variables at the Red Cross database. An Index on Social

Vulnerability in Spain is produced annually, both for adults and for

children.

Collective vulnerability

Collective

vulnerability is a state in which the integrity and social fabric of a

community is or was threatened through traumatic events or repeated

collective violence. In addition, according to the collective vulnerability hypothesis,

shared experience of vulnerability and the loss of shared normative

references can lead to collective reactions aimed to reestablish the

lost norms and trigger forms of collective resilience.

This theory has been developed by social psychologists to study

the support for human rights. It is rooted in the consideration that

devastating collective events are sometimes followed by claims for

measures that may prevent that similar event will happen again. For

instance, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

was a direct consequence of World War II horrors. Psychological

research by Willem Doise and colleagues shows indeed that after people

have experienced a collective injustice, they are more likely to support

the reinforcement of human rights.

Populations who collectively endured systematic human rights violations

are more critical of national authorities and less tolerant of rights

violations. Some analyses performed by Dario Spini, Guy Elcheroth and Rachel Fasel

on the Red Cross' “People on War” survey shows that when individuals

have direct experience with the armed conflict are less keen to support

humanitarian norms. However, in countries in which most of the social

groups in conflict share a similar level of victimization, people

express more the need for reestablishing protective social norms as the

human rights, no matter the magnitude of the conflict.

Research opportunities and challenges

Research

on social vulnerability is expanding rapidly to fill the research and

action gaps in this field. This work can be characterized in three major

groupings, including research, public awareness, and policy. The

following issues have been identified as requiring further attention to

understand and reduce social vulnerability (Warner and Loster 2006):

- Research

1. Foster a common understanding of social vulnerability – its definition(s), theories, and measurement approaches.

2. Aim for science that produces tangible and applied outcomes.

3. Advance tools and methodologies to reliably measure social vulnerability.

- Public awareness

4. Strive for better understanding of nonlinear relationships and

interacting systems (environment, social and economic, hazards), and

present this understanding coherently to maximize public understanding.

5. Disseminate and present results in a coherent manner for the

use of lay audiences. Develop straight forward information and practical

education tools.

6. Recognize the potential of the media as a bridging device between science and society.

- Policy

7. Involve local communities and stakeholders considered in vulnerability studies.

8. Strengthen people's ability to help themselves, including an (audible) voice in resource allocation decisions.

9. Create partnerships that allow stakeholders from local, national, and international levels to contribute their knowledge.

10. Generate individual and local trust and ownership of vulnerability reduction efforts.

Debate and ongoing discussion surround the causes and possible

solutions to social vulnerability. In cooperation with scientists and

policy experts worldwide, momentum is gathering around practice-oriented

research on social vulnerability. In the future, links will be

strengthened between ongoing policy and academic work to solidify the

science, consolidate the research agenda, and fill knowledge gaps about

causes of and solutions for social vulnerability.