Industrial control system (ICS) is a general term that encompasses several types of control systems and associated instrumentation used for industrial process control.

Such systems can range in size from a few modular panel-mounted controllers to large interconnected and interactive distributed control systems with many thousands of field connections. Systems receive data received from remote sensors measuring process variables (PVs), compare the collected data with desired setpoints (SPs), and derive command functions which are used to control a process through the final control elements (FCEs), such as control valves.

Larger systems are usually implemented by supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, or distributed control systems (DCS), and programmable logic controllers (PLCs), though SCADA and PLC systems are scalable down to small systems with few control loops. Such systems are extensively used in industries such as chemical processing, pulp and paper manufacture, power generation, oil and gas processing, and telecommunications.

Discrete controllers

Panel

mounted controllers with integral displays. The process value (PV), and

setvalue (SV) or setpoint are on the same scale for easy comparison.

The controller output is shown as MV (manipulated variable) with range

0-100%.

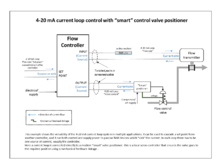

A

control loop using a discrete controller. Field signals are flow rate

measurement from the sensor, and control output to the valve. A valve

positioner ensures correct valve operation.

The simplest control systems are based around small discrete controllers with a single control loop

each. These are usually panel mounted which allows direct viewing of

the front panel and provides means of manual intervention by the

operator, either to manually control the process or to change control

setpoints. Originally these would be pneumatic controllers, a few of

which are still in use, but nearly all are now electronic.

Quite complex systems can be created with networks of these

controllers communicating using industry standard protocols. Networking

allow the use of local or remote SCADA operator interfaces, and enables

the cascading and interlocking of controllers. However, as the number of

control loops increase for a system design there is a point where the

use of a programmable logic controller (PLC) or distributed control system (DCS) is more manageable or cost-effective.

Distributed control systems

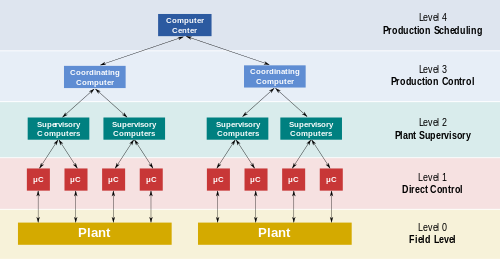

Functional

manufacturing control levels. DCS (including PLCs or RTUs) operate on

level 1. Level 2 contains the SCADA software and computing platform.

A distributed control system (DCS) is a digital processor control

system for a process or plant, wherein controller functions and field

connection modules are distributed throughout the system. As the number

of control loops grows, DCS becomes more cost effective than discrete

controllers. Additionally a DCS provides supervisory viewing and

management over large industrial processes. In a DCS, a hierarchy of

controllers is connected by communication networks, allowing centralised control rooms and local on-plant monitoring and control.

A DCS enables easy configuration of plant controls such as cascaded loops and interlocks, and easy interfacing with other computer systems such as production control.

It also enables more sophisticated alarm handling, introduces automatic

event logging, removes the need for physical records such as chart

recorders and allows the control equipment to be networked and thereby

located locally to equipment being controlled to reduce cabling.

A DCS typically uses custom-designed processors as controllers,

and uses either proprietary interconnections or standard protocols for

communication. Input and output modules form the peripheral components

of the system.

The processors receive information from input modules, process

the information and decide control actions to be performed by the output

modules. The input modules receive information from sensing instruments

in the process (or field) and the output modules transmit instructions

to the final control elements, such as control valves.

The field inputs and outputs can either be continuously changing analog signals e.g. current loop or 2 state signals that switch either on or off, such as relay contacts or a semiconductor switch.

Distributed control systems can normally also support Foundation Fieldbus, PROFIBUS, HART, Modbus

and other digital communication buses that carry not only input and

output signals but also advanced messages such as error diagnostics and

status signals.

SCADA systems

Supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) is a control system architecture that uses computers, networked data communications and graphical user interfaces

for high-level process supervisory management. The operator interfaces

which enable monitoring and the issuing of process commands, such as

controller set point changes, are handled through the SCADA supervisory

computer system. However, the real-time control logic or controller

calculations are performed by networked modules which connect to other

peripheral devices such as programmable logic controllers and discrete PID controllers which interface to the process plant or machinery.

The SCADA concept was developed as a universal means of remote

access to a variety of local control modules, which could be from

different manufacturers allowing access through standard automation protocols. In practice, large SCADA systems have grown to become very similar to distributed control systems

in function, but using multiple means of interfacing with the plant.

They can control large-scale processes that can include multiple sites,

and work over large distances.

This is a commonly-used architecture industrial control systems,

however there are concerns about SCADA systems being vulnerable to cyberwarfare or cyberterrorism attacks.

The SCADA software operates on a supervisory level as control actions are performed automatically by RTUs

or PLCs. SCADA control functions are usually restricted to basic

overriding or supervisory level intervention. A feedback control loop is

directly controlled by the RTU or PLC, but the SCADA software monitors

the overall performance of the loop. For example, a PLC may control the

flow of cooling water through part of an industrial process to a set

point level, but the SCADA system software will allow operators to

change the set points for the flow. The SCADA also enables alarm

conditions, such as loss of flow or high temperature, to be displayed

and recorded.

Programmable logic controllers

Siemens

Simatic S7-400 system in a rack, left-to-right: power supply unit

(PSU), CPU, interface module (IM) and communication processor (CP).

PLCs can range from small modular devices with tens of inputs and

outputs (I/O) in a housing integral with the processor, to large

rack-mounted modular devices with a count of thousands of I/O, and which

are often networked to other PLC and SCADA systems. They can be

designed for multiple arrangements of digital and analog inputs and

outputs, extended temperature ranges, immunity to electrical noise, and resistance to vibration and impact. Programs to control machine operation are typically stored in battery-backed-up or non-volatile memory.

History

A

pre-DCS era central control room. Whilst the controls are centralised

in one place, they are still discrete and not integrated into one

system.

A

DCS control room where plant information and controls are displayed on

computer graphics screens. The operators are seated as they can view and

control any part of the process from their screens, whilst retaining a

plant overview.

Process control

of large industrial plants has evolved through many stages. Initially,

control was from panels local to the process plant. However this

required personnel to attend to these dispersed panels, and there was no

overall view of the process. The next logical development was the

transmission of all plant measurements to a permanently-manned central

control room. Often the controllers were behind the control room panels,

and all automatic and manual control outputs were individually

transmitted back to plant in the form of pneumatic or electrical

signals. Effectively this was the centralisation of all the localised

panels, with the advantages of reduced manpower requirements and

consolidated overview of the process.

However, whilst providing a central control focus, this

arrangement was inflexible as each control loop had its own controller

hardware so system changes required reconfiguration of signals by

re-piping or re-wiring. It also required continual operator movement

within a large control room in order to monitor the whole process. With

the coming of electronic processors, high speed electronic signalling

networks and electronic graphic displays it became possible to replace

these discrete controllers with computer-based algorithms, hosted on a

network of input/output racks with their own control processors. These

could be distributed around the plant and would communicate with the

graphic displays in the control room. The concept of distributed control was realised.

The introduction of distributed control allowed flexible

interconnection and re-configuration of plant controls such as cascaded

loops and interlocks, and interfacing with other production computer

systems. It enabled sophisticated alarm handling, introduced automatic

event logging, removed the need for physical records such as chart

recorders, allowed the control racks to be networked and thereby located

locally to plant to reduce cabling runs, and provided high-level

overviews of plant status and production levels. For large control

systems, the general commercial name distributed control system

(DCS) was coined to refer to proprietary modular systems from many

manufacturers which integrated high speed networking and a full suite of

displays and control racks.

While the DCS was tailored to meet the needs of large continuous

industrial processes, in industries where combinatorial and sequential

logic was the primary requirement, the PLC evolved out of a need to

replace racks of relays and timers used for event-driven control. The

old controls were difficult to re-configure and debug, and PLC control

enabled networking of signals to a central control area with electronic

displays. PLC were first developed for the automotive industry on

vehicle production lines, where sequential logic was becoming very

complex.

It was soon adopted in a large number of other event-driven

applications as varied as printing presses and water treatment plants.

SCADA's history is rooted in distribution applications, such as

power, natural gas, and water pipelines, where there is a need to gather

remote data through potentially unreliable or intermittent

low-bandwidth and high-latency links. SCADA systems use open-loop control with sites that are widely separated geographically. A SCADA system uses remote terminal units

(RTUs) to send supervisory data back to a control center. Most RTU

systems always had some capacity to handle local control while the

master station is not available. However, over the years RTU systems

have grown more and more capable of handling local control.

The boundaries between DCS and SCADA/PLC systems are blurring as time goes on.

The technical limits that drove the designs of these various systems

are no longer as much of an issue. Many PLC platforms can now perform

quite well as a small DCS, using remote I/O and are sufficiently

reliable that some SCADA systems actually manage closed loop control

over long distances. With the increasing speed of today's processors,

many DCS products have a full line of PLC-like subsystems that weren't

offered when they were initially developed.

In 1993, with the release of IEC-1131, later to become IEC-61131-3,

the industry moved towards increased code standardization with

reusable, hardware-independent control software. For the first time, object-oriented programming

(OOP) became possible within industrial control systems. This led to

the development of both programmable automation controllers (PAC) and

industrial PCs (IPC). These are platforms programmed in the five

standardized IEC languages: ladder logic, structured text, function

block, instruction list and sequential function chart. They can also be

programmed in modern high-level languages such as C or C++.

Additionally, they accept models developed in analytical tools such as MATLAB and Simulink. Unlike traditional PLCs, which use proprietary operating systems, IPCs utilize Windows IoT.

IPC's have the advantage of powerful multi-core processors with much

lower hardware costs than traditional PLCs and fit well into multiple

form factors such as DIN rail mount, combined with a touch-screen as a panel PC,

or as an embedded PC. New hardware platforms and technology have

contributed significantly to the evolution of DCS and SCADA systems,

further blurring the boundaries and changing definitions.