| Helicobacter pylori | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Campylobacter pylori |

| |

| Immunohistochemical staining of H. pylori (brown) from a gastric biopsy | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | None, abdominal pain, nausea |

| Complications | Stomach ulcer, stomach cancer |

| Causes | Helicobacter pylori spread by fecal oral route |

| Diagnostic method | Urea breath test, fecal antigen assay, tissue biopsy |

| Medication | Proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, metronidazole |

| Frequency | >50% |

Helicobacter pylori, previously known as Campylobacter pylori, is a gram-negative, helically-shaped, microaerophilic bacterium usually found in the stomach. Its helical shape (from which the genus name, helicobacter, derives) is thought to have evolved in order to penetrate the mucoid lining of the stomach and thereby establish infection. The bacterium was first identified in 1982 by Australian doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, who found that it was present in a person with chronic gastritis and gastric ulcers, conditions not previously believed to have a microbial cause. HP has been associated with the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in the stomach, esophagus, colon, rectum, or tissues around the eye (termed extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the cited organ), and of lymphoid tissue in the stomach (termed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma).

Many investigators have proposed causal associations between H. pylori and a wide range of other diseases (e.g. idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, iron deficiency anemia, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, coronary artery disease, periodontitis, Parkinson's disease, Guillain–Barré syndrome, rosacea, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, spot baldness, various autoimmune skin diseases, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, low blood levels of vitamin B12, autoimmune neutropenia, the antiphospholipid syndrome, plasma cell dyscrasias, central serous chorioretinitis, open angle glaucoma, blepharitis, diabetes mellitus, the metabolic syndrome, various types of allergies, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis, and liver cancer). The bacterial infection has also been proposed to have protective effects for its hosts against infections by other pathogens, asthma, obesity, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and esophageal cancer. However, these deleterious and protective effects have frequently been based on correlative rather than direct relationship studies and have often been contradicted by other studies that show either the opposite or no effect on the cited disease. Consequently, many of these relationships are currently regarded as questionable and in need of more definitive studes. They are not considered further here.

Some studies suggest that H. pylori plays an important role in the natural stomach ecology, e.g. by influencing the type of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract. Other studies suggest that non-pathogenic strains of H. pylori may be beneficial, e.g., by normalizing stomach acid secretion, and may play a role in regulating appetite, since the bacterium's presence in the stomach results in a persistent but reversible reduction in the level of ghrelin, a hormone that increases appetite.

In general, over 50% of the world's population has H. pylori in their upper gastrointestinal tracts with this infection (or colonization) being more common in developing countries. In recent decades, however the prevalence of H. pylori colonization of the gastrointestinal tract has declined in many countries. This is attributed to improved socioeconomic conditions: in the United States of America, for example, the prevalence of H. pylori, as detected by endoscopy conducted on a referral population, fell from 65.8 to 6.8% over a recent 10-year period while over the same time period in some developing countries H. pylori colonization remained very common with prevalence levels as high as 80%. In all events, H. pylori infection is usually asymptomatic, being associated with overt disease (commonly gastritis or peptic ulcers rather than the relatively very rarely occurring cancers) in less than 20% of cases.

Signs and symptoms

Up to 90% of people infected with H. pylori never experience symptoms or complications. However, individuals infected with H. pylori have a 10 to 20% lifetime risk of developing peptic ulcers. Acute infection may appear as an acute gastritis with abdominal pain (stomach ache) or nausea. Where this develops into chronic gastritis, the symptoms, if present, are often those of non-ulcer dyspepsia: stomach pains, nausea, bloating, belching, and sometimes vomiting.

Pain typically occurs when the stomach is empty, between meals, and in

the early morning hours, but it can also occur at other times. Less

common ulcer symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.

Bleeding in the stomach can also occur as evidenced by the passage of

black stools; prolonged bleeding may cause anemia leading to weakness and fatigue. If bleeding is heavy, hematemesis, hematochezia, or melena may occur. Inflammation of the pyloric antrum, which connects the stomach to the duodenum, is more likely to lead to duodenal ulcers, while inflammation of the corpus (i.e. body of the stomach) is more likely to lead to gastric ulcers. Individuals infected with H. pylori may also develop colorectal or gastric polyps, i.e. a non-cancerous growth of tissue projecting from the mucous membranes

of these organs. Usually, these polyps are asymptomatic but gastric

polyps may be the cause of dyspepsia, heartburn, bleeding from the upper

gastrointestinal tract, and, rarely, gastric outlet obstruction while colorectal polyps may be the cause of rectal bleeding, anemia, constipation, diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain.

Individuals with chronic H. pylori infection have an increased risk of acquiring a cancer that is directly related to this infection. These cancers are stomach adenocarcinoma, less commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach, or extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the stomach, or, more rarely, of the colon, rectum, esophagus, or ocular adenexa (i.e. orbit, conjunctiva, and/or eyelids). The signs, symptoms, pathophysiology, and diagnoses of these cancers are given in the cited linkages.

Microbiology

| Helicobacter pylori | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Epsilonproteobacteria |

| Order: | Campylobacterales |

| Family: | Helicobacteraceae |

| Genus: | Helicobacter |

| Species: |

H. pylori

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helicobacter pylori

(Marshall et al. 1985) Goodwin et al., 1989

| |

Morphology

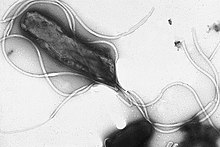

Helicobacter pylori is a helix-shaped (classified as a curved rod, not spirochaete) Gram-negative bacterium about 3 μm long with a diameter of about 0.5μm. H. pylori

can be demonstrated in tissue by Gram stain, Giemsa stain,

haematoxylin–eosin stain, Warthin–Starry silver stain, acridine orange

stain, and phase-contrast microscopy. It is capable of forming biofilms and can convert from spiral to a possibly viable but nonculturable coccoid form.

Helicobacter pylori has four to six flagella at the same location; all gastric and enterohepatic Helicobacter species are highly motile owing to flagella. The characteristic sheathed flagellar filaments of Helicobacter are composed of two copolymerized flagellins, FlaA and FlaB.

Physiology

Helicobacter pylori is microaerophilic—that is, it requires oxygen, but at lower concentration than in the atmosphere. It contains a hydrogenase that can produce energy by oxidizing molecular hydrogen (H2) made by intestinal bacteria. It produces oxidase, catalase, and urease.

H. pylori possesses five major outer membrane protein families. The largest family includes known and putative adhesins. The other four families are porins, iron transporters, flagellum-associated proteins, and proteins of unknown function. Like other typical Gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane of H. pylori consists of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The O antigen of LPS may be fucosylated and mimic Lewis blood group antigens found on the gastric epithelium. The outer membrane also contains cholesterol glucosides, which are present in few other bacteria.

Genome

Helicobacter pylori consists of a large diversity of strains, and hundreds of genomes have been completely sequenced. The genome of the strain "26695" consists of about 1.7 million base pairs,

with some 1,576 genes. The pan-genome, that is a combined set of 30

sequenced strains, encodes 2,239 protein families (orthologous groups,

OGs). Among them, 1248 OGs are conserved in all the 30 strains, and

represent the universal core. The remaining 991 OGs correspond to the accessory genome in which 277 OGs are unique (i.e., OGs present in only one strain).

Transcriptome

In 2010, Sharma et al. presented a comprehensive analysis of transcription at single-nucleotide resolution by differential RNA-seq that confirmed the known acid induction of major virulence loci, such as the urease (ure) operon or the cag pathogenicity island (see below). More importantly, this study identified a total of 1,907 transcriptional start sites, 337 primary operons, and 126 additional suboperons, and 66 monocistrons.

Until 2010, only about 55 transcriptional start sites (TSSs) were known

in this species. Notably, 27% of the primary TSSs are also antisense

TSSs, indicating that—similar to E. coli—antisense transcription occurs across the entire H. pylori genome. At least one antisense TSS is associated with about 46% of all open reading frames, including many housekeeping genes. Most (about 50%) of the 5' UTRs

are 20–40 nucleotides (nt) in length and support the AAGGag motif

located about 6 nt (median distance) upstream of start codons as the

consensus Shine–Dalgarno sequence in H. pylori.

Genes involved in virulence and pathogenesis

Study of the H. pylori genome is centered on attempts to understand pathogenesis, the ability of this organism to cause disease. About 29% of the loci have a colonization defect when mutated. Two of sequenced strains have an around 40-kb-long Cag pathogenicity island (a common gene sequence believed responsible for pathogenesis) that contains over 40 genes. This pathogenicity island is usually absent from H. pylori strains isolated from humans who are carriers of H. pylori, but remain asymptomatic.

The cagA gene codes for one of the major H. pylori virulence proteins. Bacterial strains with the cagA gene are associated with an ability to cause ulcers. The cagA gene codes for a relatively long (1186-amino acid) protein. The cag pathogenicity island (PAI) has about 30 genes, part of which code for a complex type IV secretion system. The low GC-content of the cag PAI relative to the rest of the Helicobacter genome suggests the island was acquired by horizontal transfer from another bacterial species. The serine protease HtrA also plays a major role in the pathogenesis of H. pylori. The HtrA protein enables the bacterium to transmigrate

across the host cells' epithelium, and is also needed for the translocation of CagA.

Pathophysiology

Adaptation to the stomach

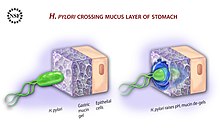

Diagram showing how H. pylori reaches the epithelium of the stomach

To avoid the acidic environment of the interior of the stomach (lumen), H. pylori uses its flagella to burrow into the mucus lining of the stomach to reach the epithelial cells underneath, where it is less acidic. H. pylori is able to sense the pH gradient in the mucus and move towards the less acidic region (chemotaxis).

This also keeps the bacteria from being swept away into the lumen with

the bacteria's mucus environment, which is constantly moving from its

site of creation at the epithelium to its dissolution at the lumen

interface.

H. pylori urease enzyme diagram

H. pylori is found in the mucus, on the inner surface of the epithelium, and occasionally inside the epithelial cells themselves. It adheres to the epithelial cells by producing adhesins, which bind to lipids and carbohydrates in the epithelial cell membrane. One such adhesin, BabA, binds to the Lewis b antigen displayed on the surface of stomach epithelial cells. H. pylori

adherence via BabA is acid sensitive and can be fully reversed by

decreased pH. It has been proposed that BabA's acid responsiveness

enables adherence while also allowing an effective escape from

unfavorable environment at pH that is harmful to the organism. Another such adhesin, SabA, binds to increased levels of sialyl-Lewis x antigen expressed on gastric mucosa.

In addition to using chemotaxis to avoid areas of low pH, H. pylori also neutralizes the acid in its environment by producing large amounts of urease, which breaks down the urea present in the stomach to carbon dioxide and ammonia. These react with the strong acids in the environment to produce a neutralized area around H. pylori.

Urease knockout mutants are incapable of colonization. In fact, urease

expression is not only required for establishing initial colonization

but also for maintaining chronic infection.

Inflammation, gastritis and ulcer

Helicobacter pylori harms the stomach and duodenal

linings by several mechanisms. The ammonia produced to regulate pH is

toxic to epithelial cells, as are biochemicals produced by H. pylori such as proteases, vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) (this damages epithelial cells, disrupts tight junctions and causes apoptosis), and certain phospholipases. Cytotoxin associated gene CagA can also cause inflammation and is potentially a carcinogen.

Colonization of the stomach by H. pylori can result in chronic gastritis, an inflammation of the stomach lining, at the site of infection. Helicobacter cysteine-rich proteins (Hcp), particularly HcpA (hp0211), are known to trigger an immune response, causing inflammation. H. Pylori has been shown to increase the levels of COX2 in H. Pylori positive gastritis.

Chronic gastritis is likely to underlie H. pylori-related diseases.

Ulcers in the stomach and duodenum result when the consequences of inflammation allow stomach acid and the digestive enzyme pepsin to overwhelm the mechanisms that protect the stomach and duodenal mucous membranes. The location of colonization of H. pylori, which affects the location of the ulcer, depends on the acidity of the stomach.

In people producing large amounts of acid, H. pylori colonizes near the pyloric antrum (exit to the duodenum) to avoid the acid-secreting parietal cells at the fundus (near the entrance to the stomach). In people producing normal or reduced amounts of acid, H. pylori can also colonize the rest of the stomach.

The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone gastrin, which travels through the bloodstream to parietal cells in the fundus.

Gastrin stimulates the parietal cells to secrete more acid into the

stomach lumen, and over time increases the number of parietal cells, as

well. The increased acid load damages the duodenum, which may eventually result in ulcers forming in the duodenum.

When H. pylori colonizes other areas of the stomach, the inflammatory response can result in atrophy of the stomach lining and eventually ulcers in the stomach. This also may increase the risk of stomach cancer.

Cag pathogenicity island

The pathogenicity of H. pylori may be increased by genes of the cag pathogenicity island; about 50–70% of H. pylori strains in Western countries carry it. Western people infected with strains carrying the cag

PAI have a stronger inflammatory response in the stomach and are at a

greater risk of developing peptic ulcers or stomach cancer than those

infected with strains lacking the island. Following attachment of H. pylori to stomach epithelial cells, the type IV secretion system expressed by the cag PAI "injects" the inflammation-inducing agent, peptidoglycan, from their own cell walls into the epithelial cells. The injected peptidoglycan is recognized by the cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptor (immune sensor) Nod1, which then stimulates expression of cytokines that promote inflammation.

The type-IV secretion apparatus also injects the cag PAI-encoded protein CagA into the stomach's epithelial cells, where it disrupts the cytoskeleton, adherence to adjacent cells, intracellular signaling, cell polarity, and other cellular activities. Once inside the cell, the CagA protein is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues by a host cell membrane-associated tyrosine kinase (TK). CagA then allosterically activates protein tyrosine phosphatase/protooncogene Shp2. Pathogenic strains of H. pylori have been shown to activate the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a membrane protein with a TK domain. Activation of the EGFR by H. pylori is associated with altered signal transduction and gene expression in host epithelial cells that may contribute to pathogenesis. A C-terminal region of the CagA protein (amino acids 873–1002) has also been suggested to be able to regulate host cell gene transcription, independent of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. A great deal of diversity exists between strains of H. pylori, and the strain that infects a person can predict the outcome.

Cancer

Two related mechanisms by which H. pylori could promote cancer are under investigation. One mechanism involves the enhanced production of free radicals near H. pylori and an increased rate of host cell mutation. The other proposed mechanism has been called a "perigenetic pathway", and involves enhancement of the transformed host cell phenotype by means of alterations in cell proteins, such as adhesion proteins. H. pylori has been proposed to induce inflammation and locally high levels of TNF-α and/or interleukin 6

(IL-6). According to the proposed perigenetic mechanism,

inflammation-associated signaling molecules, such as TNF-α, can alter

gastric epithelial cell adhesion and lead to the dispersion and

migration of mutated epithelial cells without the need for additional

mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as genes that code for cell adhesion proteins.

The strain of H. pylori a person is exposed to may influence the risk of developing gastric cancer. Strains of H. pylori

that produce high levels of two proteins, vacuolating toxin A (VacA)

and the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), appear to cause greater

tissue damage than those that produce lower levels or that lack those

genes completely.

These proteins are directly toxic to cells lining the stomach and

signal strongly to the immune system that an invasion is under way. As a

result of the bacterial presence, neutrophils and macrophages set up residence in the tissue to fight the bacteria assault.

Survival of Helicobacter pylori

The pathogenesis of H. pylori depends on its ability to survive in the harsh gastric environment characterized by acidity, peristalsis, and attack by phagocytes accompanied by release of reactive oxygen species. In particular, H. pylori

elicits an oxidative stress response during host colonization. This

oxidative stress response induces potentially lethal and mutagenic

oxidative DNA adducts in the H. pylori genome.

Vulnerability to oxidative stress and oxidative DNA damage occurs commonly in many studied bacterial pathogens, including Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Hemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. mutans, and H. pylori.

For each of these pathogens, surviving the DNA damage induced by

oxidative stress appears supported by transformation-mediated

recombinational repair. Thus, transformation and recombinational repair

appear to contribute to successful infection.

Transformation

(the transfer of DNA from one bacterial cell to another through the

intervening medium) appears to be part of an adaptation for DNA repair.

H. pylori is naturally competent for transformation. While many

organisms are competent only under certain environmental conditions,

such as starvation, H. pylori is competent throughout logarithmic growth. All organisms encode genetic programs for response to stressful conditions including those that cause DNA damage. In H. pylori,

homologous recombination is required for repairing DNA double-strand

breaks (DSBs). The AddAB helicase-nuclease complex resects DSBs and

loads RecA onto single-strand DNA (ssDNA), which then mediates strand

exchange, leading to homologous recombination and repair. The

requirement of RecA plus AddAB for efficient gastric colonization

suggests, in the stomach, H. pylori is either exposed to

double-strand DNA damage that must be repaired or requires some other

recombination-mediated event. In particular, natural transformation is

increased by DNA damage in H. pylori, and a connection exists between the DNA damage response and DNA uptake in H. pylori, suggesting natural competence contributes to persistence of H. pylori in its human host and explains the retention of competence in most clinical isolates.

RuvC protein is essential to the process of recombinational

repair, since it resolves intermediates in this process termed Holliday

junctions. H. pylori mutants that are defective in RuvC have

increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and to oxidative stress,

exhibit reduced survival within macrophages, and are unable to establish

successful infection in a mouse model. Similarly, RecN protein plays an important role in DSB repair in H. pylori. An H. pylori recN

mutant displays an attenuated ability to colonize mouse stomachs,

highlighting the importance of recombinational DNA repair in survival of

H. pylori within its host.

Diagnosis

H. pylori colonized on the surface of regenerative epithelium (Warthin-Starry silver stain)

Colonization with H. pylori is not a disease in and of itself, but a condition associated with a number of disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Testing for H. pylori is not routinely recommended. Testing is recommended if peptic ulcer disease or low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma is present, after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer, for first-degree relatives with gastric cancer, and in certain cases of dyspepsia. Several methods of testing exist, including invasive and noninvasive testing methods.

Noninvasive tests for H. pylori infection may be suitable and include blood antibody tests, stool antigen tests, or the carbon urea breath test (in which the patient drinks 14C—or 13C-labelled urea, which the bacterium metabolizes, producing labelled carbon dioxide that can be detected in the breath). It is not known which non-invasive test is more accurate for diagnosing a H. pylori infection, and the clinical significance of the levels obtained with these tests are not clear. Some drugs can affect H. pylori urease activity and give false negatives with the urea-based tests.

An endoscopic biopsy is an invasive means to test for H. pylori

infection. Low-level infections can be missed by biopsy, so multiple

samples are recommended. The most accurate method for detecting H. pylori infection is with a histological examination from two sites after endoscopic biopsy, combined with either a rapid urease test or microbial culture.

Transmission

Helicobacter pylori is contagious, although the exact route of transmission is not known.

Person-to-person transmission by either the oral–oral or fecal–oral route is most likely. Consistent with these transmission routes, the bacteria have been isolated from feces, saliva, and dental plaque of some infected people. Findings suggest H. pylori is more easily transmitted by gastric mucus than saliva.

Transmission occurs mainly within families in developed nations, yet

can also be acquired from the community in developing countries. H. pylori

may also be transmitted orally by means of fecal matter through the

ingestion of waste-tainted water, so a hygienic environment could help

decrease the risk of H. pylori infection.

Prevention

Due to H. pylori's role as a major cause of certain diseases (particularly cancers) and its consistently increasing antibiotic resistance, there is a clear need for new therapeutic strategies to prevent or remove the bacterium from colonizing humans. Much work has been done on developing viable vaccines aimed at providing an alternative strategy to control H. pylori infection and related diseases. Researchers are studying different adjuvants, antigens,

and routes of immunization to ascertain the most appropriate system of

immune protection; however, most of the research only recently moved

from animal to human trials. An economic evaluation of the use of a potential H. pylori vaccine in babies found its introduction could, at least in the Netherlands, prove cost-effective for the prevention of peptic ulcer and stomach adenocarcinoma. A similar approach has also been studied for the United States. Notwithstanding this proof-of-concept (i.e. vaccination protects children from acquisition of infection with H. pylori),

as of late 2019 there have been no advanced vaccine candidates and only

one vaccine in a Phase I clinical trial. Furthermore, development of a

vaccine against H. pylori has not been a current priority of major pharmaceutical companies.

Many investigations have attempted to prevent the development of Helicobacter pylori-related

diseases by eradicating the bacterium during an early stages of its

infestation using antibiotic-based drug regimens. Studies find that such

treatments, when effectively eradicating H. pylori from the stomach, reduce the inflammation and some of the histopathological

abnormalities associated with the infestation. However studies disagree

on the ability of these treatments to alleviate the more serious

histopathological abnormalities in H. pylori infections, e.g. gastric atrophy and metaplasia, both of which are precursors to gastric adenocarcinoma.

There is similar disagreement on the ability of antibiotic-based

regiments to prevent gastric adenocarcinoma. A meta-analysis (i.e. a

statistical analysis that combines the results of multiple randomized controlled trials) published in 2014 found that these regimens did not appear to prevent development of this adenocarcinoma. However, two subsequent prospective cohort studies

conducted on high-risk individuals in China and Taiwan found that

eradication of the bacterium produced a significant decrease in the

number of individuals developing the disease. These results agreed with a

retrospective cohort study done in Japan and published in 2016 as well as a meta-analysis, also published in 2016, of 24 studies conducted on individuals with varying levels of risk for developing the disease. These more recent studies suggest that the eradication of H. pylori infection reduces the incidence of H. pylori-related gastric adenocarcinoma in individuals at all levels of baseline risk.

Further studies will be required to clarify this issue. In all events,

studies agree that antibiotic-based regimens effectively reduce the

occurrence of metachronous H. pylori-associated gastric adenocarcinoma.

(Metachronus cancers are cancers that reoccur 6 months or later after

resection of the original cancer.) It is suggested that antibiotic-based

drug regimens be used after resecting H. pylori-associated gastric adenocarcinoma in order to reduce its metachronus reoccurrence.

Treatment

Gastritis

Superficial gastritis, either acute or chronic, is the most common manifestation of H. pylori

infection. The signs and symptoms of this gastritis have been found to

remit spontaneously in many individuals without resorting to Helicobacter pylori eradication protocols. The H. Pylori bacterial infection persists after remission in these cases. Various antibiotic plus proton pump inhibitor drug regimens are used to eradicate the bacterium and thereby successfully treat the disorder with triple-drug therapy consisting of clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and a proton-pump inhibitor given for 14–21 days often being considered first line treatment.

Peptic ulcers

Once H. pylori is detected in a person with a peptic ulcer, the normal procedure is to eradicate it and allow the ulcer to heal. The standard first-line therapy is a one-week "triple therapy" consisting of proton-pump inhibitors such as omeprazole and the antibiotics clarithromycin and amoxicillin. (The actions of proton pump inhibitors against H. pylori may reflect their direct bacteriostatic effect due to inhibition of the bacterium's P-type ATPase and/or urease.) Variations of the triple therapy have been developed over the years, such as using a different proton pump inhibitor, as with pantoprazole or rabeprazole, or replacing amoxicillin with metronidazole for people who are allergic to penicillin. In areas with higher rates of clarithromycin resistance, other options are recommended.

Such a therapy has revolutionized the treatment of peptic ulcers and

has made a cure to the disease possible. Previously, the only option was

symptom control using antacids, H2-antagonists or proton pump inhibitors alone.

Antibiotic-resistant disease

An increasing number of infected individuals are found to harbor antibiotic-resistant

bacteria. This results in initial treatment failure and requires

additional rounds of antibiotic therapy or alternative strategies, such

as a quadruple therapy, which adds a bismuth colloid, such as bismuth subsalicylate. For the treatment of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori, the use of levofloxacin as part of the therapy has been suggested.

Ingesting lactic acid bacteria exerts a suppressive effect on H. pylori infection in both animals and humans, and supplementing with Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt improved the rates of eradication of H. pylori in humans.

Symbiotic butyrate-producing bacteria which are normally present in the

intestine are sometimes used as probiotics to help suppress H. pylori infections as an adjunct to antibiotic therapy. Butyrate itself is an antimicrobial which destroys the cell envelope of H. pylori by inducing regulatory T cell expression (specifically, FOXP3) and synthesis of an antimicrobial peptide called LL-37, which arises through its action as a histone deacetylase inhibitor.

The substance sulforaphane, which occurs in broccoli and cauliflower, has been proposed as a treatment. Periodontal therapy or scaling and root planing has also been suggested as an additional treatment.

Cancers

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas are generally indolent malignancies. Recommended treatment of H. pylori-positive extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the stomach, when localized (i.e. Ann Arbor stage I and II), employs one of the antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor regiments listed in the H. pylori eradication protocols.

If the initial regimen fails to eradicate the pathogen, patients are

treated with an alternate protocol. Eradication of the pathogen is

successful in 70–95% of cases.

Some 50-80% of patients who experience eradication of the pathogen

develop within 3–28 months a remission and long-term clinical control of

their lymphoma. Radiation therapy

to the stomach and surrounding (i.e. peri-gastric) lymph nodes has also

been used to successfully treat these localized cases. Patients with

non-localized (i.e. systemic Ann Arbor stage III and IV) disease who are

free of symptoms have been treated with watchful waiting or, if symptomatic, with the immunotherapy drug, rituximab, (given for 4 weeks) combined with the chemotherapy drug, chlorambucil,

for 6–12 months; 58% of these patients attain a 58% progression-free

survival rate at 5 years. Frail stage III/IV patients have been

successfully treated with rituximab or the chemotherapy drug, cyclophosphamide, alone. Only rare cases of H. pylori-positive

extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the colon have been

successfully treated with an antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor regimen;

the currently recommended treatments for this disease are surgical

resection, endoscopic resection, radiation, chemotherapy, or, more

recently, rituximab. In the few reported cases of H. pylori-positive

extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the esophagus, localized

disease has been successfully treated with antibiotic-proton pump

inhibitor regimens; however, advanced disease appears less responsive or

unresponsive to these regimens but partially responsive to rituximab.

Antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor eradication therapy and localized

radiation therapy have been used successfully to treat H.pylori-positive

extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the rectum; however

radiation therapy has given slightly better results and therefore been

suggested to be the disease' preferred treatment. The treatment of localized H. pylori-positive

extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the ocular adenexa with

antibiotic/proton pump inhibitor regimens has achieved 2 year and 5 year

failure-free survival rates of 67% and 55%, respectively, and a 5-year

progression-free rate of 61%.

However, the generally recognized treatment of choice for patients with

systemic involvement uses various chemotherapy drugs often combined

with rituximab.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a far more aggressive cancer than

extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Cases of this malignancy that

are H. pylori-positive may be derived from the latter lymphoma and are less aggressive as well as more susceptible to treatment than H. pylori negative cases. Several recent studies strongly suggest that localized, early-stage diffuse Helicobacter pylori

positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, when limited to the stomach,

can be successfully treated with antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor

regimens.

However, these studies also agree that, given the aggressiveness of

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, patients treated with one of these H. pylori

eradication regimes need to be carefully followed. If found

unresponsive to or clinically worsening on these regimens, these

patients should be switched to more conventional therapy such as

chemotherapy (e.g. CHOP or a CHOP-like regimen), immunotherapy (e.g. rituximab), surgery, and/or local radiotherapy. H. pylori positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has been successfully treated with one or a combination of these methods.

Stomach adenocarcinoma

Helicobacter

pylori is linked to the majority of gastric adenocarcinoma cases,

particularly those that are located outside of the stomach's cardia (i.e. esophagus-stomach junction).

The treatment for this cancer is highly aggressive with even localized

disease being treated sequentially with chemotherapy and radiotherapy

before surgical resection. Since this cancer, once developed, is independent of H. pylori infection, antibiotic-proton pump inhibitor regimens are not used in its treatment.

Prognosis

Helicobacter pylori colonizes the stomach and induces chronic gastritis,

a long-lasting inflammation of the stomach. The bacterium persists in

the stomach for decades in most people. Most individuals infected by H. pylori never experience clinical symptoms, despite having chronic gastritis. About 10–20% of those colonized by H. pylori ultimately develop gastric and duodenal ulcers. H. pylori infection is also associated with a 1–2% lifetime risk of stomach cancer and a less than 1% risk of gastric MALT lymphoma.

In the absence of treatment, H. pylori infection—once established in its gastric niche—is widely believed to persist for life. In the elderly, however, infection likely can disappear as the stomach's mucosa becomes increasingly atrophic

and inhospitable to colonization. The proportion of acute infections

that persist is not known, but several studies that followed the natural

history in populations have reported apparent spontaneous elimination.

Mounting evidence suggests H. pylori has an important role in protection from some diseases. The incidence of acid reflux disease, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal cancer have been rising dramatically at the same time as H. pylori's presence decreases. In 1996, Martin J. Blaser advanced the hypothesis that H. pylori has a beneficial effect by regulating the acidity of the stomach contents. The hypothesis is not universally accepted as several randomized controlled trials failed to demonstrate worsening of acid reflux disease symptoms following eradication of H. pylori. Nevertheless, Blaser has reasserted his view that H. pylori is a member of the normal flora of the stomach. He postulates that the changes in gastric physiology caused by the loss of H. pylori account for the recent increase in incidence of several diseases, including type 2 diabetes, obesity, and asthma. His group has recently shown that H. pylori colonization is associated with a lower incidence of childhood asthma.

Epidemiology

At least half the world's population is infected by the bacterium, making it the most widespread infection in the world. Actual infection rates vary from nation to nation; the developing world has much higher infection rates than the West (Western Europe, North America, Australasia), where rates are estimated to be around 25%.

The age when someone acquires this bacterium seems to influence

the pathologic outcome of the infection. People infected at an early age

are likely to develop more intense inflammation that may be followed by

atrophic gastritis with a higher subsequent risk of gastric ulcer,

gastric cancer, or both. Acquisition at an older age brings different

gastric changes more likely to lead to duodenal ulcer. Infections are usually acquired in early childhood in all countries. However, the infection rate of children in developing nations is higher than in industrialized nations,

probably due to poor sanitary conditions, perhaps combined with lower

antibiotics usage for unrelated pathologies. In developed nations, it is

currently uncommon to find infected children, but the percentage of

infected people increases with age, with about 50% infected for those

over the age of 60 compared with around 10% between 18 and 30 years.

The higher prevalence among the elderly reflects higher infection rates

in the past when the individuals were children rather than more recent

infection at a later age of the individual. In the United States, prevalence appears higher in African-American and Hispanic populations, most likely due to socioeconomic factors.

The lower rate of infection in the West is largely attributed to higher

hygiene standards and widespread use of antibiotics. Despite high rates

of infection in certain areas of the world, the overall frequency of H. pylori infection is declining. However, antibiotic resistance is appearing in H. pylori; many metronidazole- and clarithromycin-resistant strains are found in most parts of the world.

History

Helicobacter pylori migrated out of Africa along with its human host circa 60,000 years ago. Recent research states that genetic diversity in H. pylori, like that of its host, decreases with geographic distance from East Africa.

Using the genetic diversity data, researchers have created simulations

that indicate the bacteria seem to have spread from East Africa around

58,000 years ago. Their results indicate modern humans were already

infected by H. pylori before their migrations out of Africa, and it has remained associated with human hosts since that time.

H. pylori was first discovered in the stomachs of patients with gastritis and ulcers in 1982 by Drs. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren of Perth, Western Australia.

At the time, the conventional thinking was that no bacterium could live

in the acid environment of the human stomach. In recognition of their

discovery, Marshall and Warren were awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Before the research of Marshall and Warren, German scientists found spiral-shaped bacteria in the lining of the human stomach in 1875, but they were unable to culture them, and the results were eventually forgotten. The Italian researcher Giulio Bizzozero described similarly shaped bacteria living in the acidic environment of the stomach of dogs in 1893. Professor Walery Jaworski of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków investigated sediments of gastric washings obtained by lavage from humans in 1899. Among some rod-like bacteria, he also found bacteria with a characteristic spiral shape, which he called Vibrio rugula.

He was the first to suggest a possible role of this organism in the

pathogenesis of gastric diseases. His work was included in the Handbook of Gastric Diseases, but it had little impact, as it was written in Polish.

Several small studies conducted in the early 20th century demonstrated

the presence of curved rods in the stomachs of many people with peptic

ulcers and stomach cancers.

Interest in the bacteria waned, however, when an American study

published in 1954 failed to observe the bacteria in 1180 stomach

biopsies.

Interest in understanding the role of bacteria in stomach

diseases was rekindled in the 1970s, with the visualization of bacteria

in the stomachs of people with gastric ulcers.

The bacteria had also been observed in 1979, by Robin Warren, who

researched it further with Barry Marshall from 1981. After unsuccessful

attempts at culturing the bacteria from the stomach, they finally

succeeded in visualizing colonies in 1982, when they unintentionally

left their Petri dishes incubating for five days over the Easter

weekend. In their original paper, Warren and Marshall contended that

most stomach ulcers and gastritis were caused by bacterial infection and

not by stress or spicy food, as had been assumed before.

Some skepticism was expressed initially, but within a few years multiple research groups had verified the association of H. pylori with gastritis and, to a lesser extent, ulcers. To demonstrate H. pylori caused gastritis and was not merely a bystander, Marshall drank a beaker of H. pylori culture. He became ill with nausea and vomiting several days later. An endoscopy 10 days after inoculation revealed signs of gastritis and the presence of H. pylori. These results suggested H. pylori

was the causative agent. Marshall and Warren went on to demonstrate

antibiotics are effective in the treatment of many cases of gastritis.

In 1987, the Sydney gastroenterologist Thomas Borody invented the first triple therapy for the treatment of duodenal ulcers. In 1994, the National Institutes of Health stated most recurrent duodenal and gastric ulcers were caused by H. pylori, and recommended antibiotics be included in the treatment regimen.

The bacterium was initially named Campylobacter pyloridis, then renamed C. pylori in 1987 (pylori being the genitive of pylorus, the circular opening leading from the stomach into the duodenum, from the Ancient Greek word πυλωρός, which means gatekeeper.). When 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing and other research showed in 1989 that the bacterium did not belong in the genus Campylobacter, it was placed in its own genus, Helicobacter from the ancient Greek hělix/έλιξ "spiral" or "coil".

In October 1987, a group of experts met in Copenhagen to found the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), an international multidisciplinary research group and the only institution focused on H. pylori. The Group is involved with the Annual International Workshop on Helicobacter and Related Bacteria, the Maastricht Consensus Reports (European Consensus on the management of H. pylori), and other educational and research projects, including two international long-term projects:

- European Registry on H. pylori Management (Hp-EuReg) – a database systematically registering the routine clinical practice of European gastroenterologists.

- Optimal H. pylori management in primary care (OptiCare) – a long-term educational project aiming to disseminate the evidence based recommendations of the Maastricht IV Consensus to primary care physicians in Europe, funded by an educational grant from United European Gastroenterology.

Research

Results from in vitro studies suggest that fatty acids, mainly polyunsaturated fatty acids, have a bactericidal effect against H. pylori, but their in vivo effects have not been proven.