https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Keynesian_economics

New Keynesian economics is a school of contemporary macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

Two main assumptions define the New Keynesian approach to macroeconomics. Like the New Classical approach, New Keynesian macroeconomic analysis usually assumes that households and firms have rational expectations. However, the two schools differ in that New Keynesian analysis usually assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume that there is imperfect competition in price and wage setting to help explain why prices and wages can become "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.

Wage and price stickiness, and the other market failures present in New Keynesian models, imply that the economy may fail to attain full employment. Therefore, New Keynesians argue that macroeconomic stabilization by the government (using fiscal policy) and the central bank (using monetary policy) can lead to a more efficient macroeconomic outcome than a laissez faire policy would.

New Keynesian economics is a school of contemporary macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

Two main assumptions define the New Keynesian approach to macroeconomics. Like the New Classical approach, New Keynesian macroeconomic analysis usually assumes that households and firms have rational expectations. However, the two schools differ in that New Keynesian analysis usually assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume that there is imperfect competition in price and wage setting to help explain why prices and wages can become "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.

Wage and price stickiness, and the other market failures present in New Keynesian models, imply that the economy may fail to attain full employment. Therefore, New Keynesians argue that macroeconomic stabilization by the government (using fiscal policy) and the central bank (using monetary policy) can lead to a more efficient macroeconomic outcome than a laissez faire policy would.

Development of Keynesian economics model

1970s

The first wave of New Keynesian economics developed in the late 1970s. The first model of Sticky information was developed by Stanley Fischer in his 1977 article, Long-Term Contracts, Rational Expectations, and the Optimal Money Supply Rule.

He adopted a "staggered" or "overlapping" contract model. Suppose that

there are two unions in the economy, who take turns to choose wages.

When it is a union's turn, it chooses the wages it will set for the next

two periods. This contrasts with John B. Taylor's

model where the nominal wage is constant over the contract life, as was

subsequently developed in his two articles, one in 1979 "Staggered wage

setting in a macro model'. and one in 1980 "Aggregate Dynamics and Staggered Contracts".

Both Taylor and Fischer contracts share the feature that only the

unions setting the wage in the current period are using the latest

information: wages in half of the economy still reflect old information.

The Taylor model had sticky nominal wages in addition to the sticky

information: nominal wages had to be constant over the length of the

contract (two periods). These early new Keynesian theories were based

on the basic idea that, given fixed nominal wages, a monetary authority

(central bank) can control the employment rate. Since wages are fixed at

a nominal rate, the monetary authority can control the real wage (wage values adjusted for inflation) by changing the money supply and thus affect the employment rate.

1980s

Menu costs and Imperfect Competition

In the 1980s the key concept of using menu costs in a framework of imperfect competition to explain price stickiness was developed.

The concept of a lump-sum cost (menu cost) to changing the price was

originally introduced by Sheshinski and Weiss (1977) in their paper

looking at the effect of inflation on the frequency of price-changes. The idea of applying it as a general theory of Nominal Price Rigidity was simultaneously put forward by several economists in 1985–6. George Akerlof and Janet Yellen put forward the idea that due to bounded rationality firms will not want to change their price unless the benefit is more than a small amount. This bounded rationality leads to inertia in nominal prices and wages which can lead to output fluctuating at constant nominal prices and wages. Gregory Mankiw took the menu-cost idea and focused on the welfare effects of changes in output resulting from sticky prices. Michael Parkin also put forward the idea. Although the approach initially focused mainly on the rigidity of nominal prices, it was extended to wages and prices by Olivier Blanchard and Nobuhiro Kiyotaki in their influential article Monopolistic Competition and the Effects of Aggregate Demand . Huw Dixon

and Claus Hansen showed that even if menu costs applied to a small

sector of the economy, this would influence the rest of the economy and

lead to prices in the rest of the economy becoming less responsive to

changes in demand.

While some studies suggested that menu costs are too small to have much of an aggregate impact, Laurence Ball and David Romer showed in 1990 that real rigidities could interact with nominal rigidities to create significant disequilibrium.

Real rigidities occur whenever a firm is slow to adjust its real prices

in response to a changing economic environment. For example, a firm can

face real rigidities if it has market power or if its costs for inputs

and wages are locked-in by a contract.

Ball and Romer argued that real rigidities in the labor market keep a

firm's costs high, which makes firms hesitant to cut prices and lose

revenue. The expense created by real rigidities combined with the menu

cost of changing prices makes it less likely that firm will cut prices

to a market clearing level.

Even if prices are perfectly flexible, imperfect competition can

affect the influence of fiscal policy in terms of the multiplier. Huw

Dixon and Gregory Mankiw developed independently simple general

equilibrium models showing that the fiscal multiplier could be

increasing with the degree of imperfect competition in the output

market. The reason for this is that imperfect competition in the output market tends to reduce the real wage, leading to the household substituting away from consumption towards leisure. When government spending is increased, the corresponding increase in lump-sum taxation

causes both leisure and consumption to decrease (assuming that they are

both a normal good). The greater the degree of imperfect competition in

the output market, the lower the real wage and hence the more the reduction falls on leisure (i.e. households work more) and less on consumption. Hence the fiscal multiplier is less than one, but increasing in the degree of imperfect competition in the output market.

The Calvo staggered contracts model

In 1983 Guillermo Calvo wrote "Staggered Prices in a Utility-Maximizing Framework". The original article was written in a continuous time mathematical framework, but nowadays is mostly used in its discrete time

version. The Calvo model has become the most common way to model

nominal rigidity in new Keynesian models. There is a probability that

the firm can reset its price in any one period h (the hazard rate), or equivalently the probability (1-h) that the price will remain unchanged in that period (the survival rate). The probability h

is sometimes called the "Calvo probability" in this context. In the

Calvo model the crucial feature is that the price-setter does not know

how long the nominal price will remain in place, in contrast to the

Taylor model where the length of contract is known ex ante.

Coordination failure

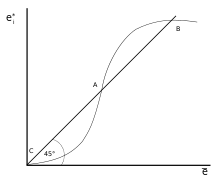

In this model of coordination failure, a representative firm ei

makes its output decisions based on the average output of all firms

(ē). When the representative firm produces as much as the average firm

(ei=ē), the economy is at an equilibrium represented by the

45 degree line. The decision curve intersects with the equilibrium line

at three equilibrium points. The firms could coordinate and produce at

the optimal level of point B, but, without coordination, firms might

produce at a less efficient equilibrium.

Coordination failure was another important new Keynesian concept developed as another potential explanation for recessions and unemployment.

In recessions a factory can go idle even though there are people

willing to work in it, and people willing to buy its production if they

had jobs. In such a scenario, economic downturns appear to be the result

of coordination failure: The invisible hand fails to coordinate the

usual, optimal, flow of production and consumption. Russell Cooper and Andrew John's 1988 paper Coordinating Coordination Failures in Keynesian Models

expressed a general form of coordination as models with multiple

equilibria where agents could coordinate to improve (or at least not

harm) each of their respective situations. Cooper and John based their work on earlier models including Peter Diamond's 1982 coconut model, which demonstrated a case of coordination failure involving search and matching theory.

In Diamond's model producers are more likely to produce if they see

others producing. The increase in possible trading partners increases

the likelihood of a given producer finding someone to trade with. As in

other cases of coordination failure, Diamond's model has multiple

equilibria, and the welfare of one agent is dependent on the decisions

of others. Diamond's model is an example of a "thick-market externality" that causes markets to function better when more people and firms participate in them. Other potential sources of coordination failure include self-fulfilling prophecies.

If a firm anticipates a fall in demand, they might cut back on hiring. A

lack of job vacancies might worry workers who then cut back on their

consumption. This fall in demand meets the firm's expectations, but it

is entirely due to the firm's own actions.

Labor market failures: Efficiency wages

New

Keynesians offered explanations for the failure of the labor market to

clear. In a Walrasian market, unemployed workers bid down wages until

the demand for workers meets the supply.

If markets are Walrasian, the ranks of the unemployed would be limited

to workers transitioning between jobs and workers who choose not to work

because wages are too low to attract them. They developed several theories explaining why markets might leave willing workers unemployed. The most important of these theories, new Keynesians was the efficiency wage theory used to explain long-term effects of previous unemployment, where short-term increases in unemployment become permanent and lead to higher levels of unemployment in the long-run.

In

the Shapiro-Stiglitz model workers are paid at a level where they do

not shirk, preventing wages from dropping to full employment levels. The

curve for the no-shirking condition (labeled NSC) goes to infinity at

full employment.

In efficiency wage models, workers are paid at levels that maximize productivity instead of clearing the market. For example, in developing countries, firms might pay more than a market rate to ensure their workers can afford enough nutrition to be productive. Firms might also pay higher wages to increase loyalty and morale, possibly leading to better productivity. Firms can also pay higher than market wages to forestall shirking. Shirking models were particularly influential.Carl Shapiro and Joseph Stiglitz's 1984 paper Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device

created a model where employees tend to avoid work unless firms can

monitor worker effort and threaten slacking employees with unemployment. If the economy is at full employment, a fired shirker simply moves to a new job.

Individual firms pay their workers a premium over the market rate to

ensure their workers would rather work and keep their current job

instead of shirking and risk having to move to a new job. Since each

firm pays more than market clearing wages, the aggregated labor market

fails to clear. This creates a pool of unemployed laborers and adds to

the expense of getting fired. Workers not only risk a lower wage, they

risk being stuck in the pool of unemployed. Keeping wages above market

clearing levels creates a serious disincentive to shirk that makes

workers more efficient even though it leaves some willing workers

unemployed.

1990s

The new neoclassical synthesis

In the early 1990s, economists began to combine the elements of new Keynesian economics developed in the 1980s and earlier with Real Business Cycle Theory.

RBC models were dynamic but assumed perfect competition; new Keynesian

models were primarily static but based on imperfect competition. The New neoclassical synthesis

essentially combined the dynamic aspects of RBC with imperfect

competition and nominal rigidities of new Keynesian models. Tack Yun was

one of the first to do this, in a model which used the Calvo pricing model.

Goodfriend and King proposed a list of four elements that are central

to the new synthesis: intertemporal optimization, rational expectations,

imperfect competition, and costly price adjustment (menu costs).

Goodfriend and King also find that the consensus models produce

certain policy implications: whilst monetary policy can affect real

output in the short-run, but there is no long-run trade-off: money is

not neutral

in the short-run but it is in the long-run. Inflation has negative

welfare effects. It is important for central banks to maintain

credibility through rules based policy like inflation targeting.

Taylor Rule

In 1993, John B Taylor formulated the idea of a Taylor rule, which is a reduced form approximation of the responsiveness of the nominal interest rate, as set by the central bank, to changes in inflation, output,

or other economic conditions. In particular, the rule describes how,

for each one-percent increase in inflation, the central bank tends raise

the nominal interest rate by more than one percentage point. This

aspect of the rule is often called the Taylor principle. Although

such rules provide concise, descriptive proxies for central bank

policy, they are not, in practice, explicitly proscriptively considered

by central banks when setting nominal rates.

Taylor's original version of the rule describes how the nominal interest rate responds to

divergences of actual inflation rates from target inflation rates and of actual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from potential GDP:

In this equation, is the target short-term nominal interest rate (e.g. the federal funds rate in the US, the Bank of England base rate in the UK), is the rate of inflation as measured by the GDP deflator, is the desired rate of inflation, is the assumed equilibrium real interest rate, is the logarithm of real GDP, and is the logarithm of potential output, as determined by a linear trend.

The New Keynesian Phillips curve

The New Keynesian Phillips curve was originally derived by Roberts in 1995, and has since been used in most state-of-the-art New Keynesian DSGE models.

The new Keynesian Phillips curve says that this period's inflation

depends on current output and the expectations of next period's

inflation. The curve is derived from the dynamic Calvo model of pricing

and in mathematical terms is:

The current period t expectations of next period's inflation are incorporated as , where is the discount factor. The constant

captures the response of inflation to output, and is largely determined

by the probability of changing price in any period, which is :

- .

The less rigid nominal prices are (the higher is ), the greater the effect of output on current inflation.

The Science of Monetary Policy

The ideas developed in the 1990s were put together to develop the new Keynesian Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium used to analyze monetary policy. This culminated in the three equation new Keynesian model found in the survey by Richard Clarida, Jordi Gali, and Mark Gertler in the Journal of Economic Literature. It combines the two equations of the new Keynesian Phillips curve and the Taylor rule with the dynamic IS curve derived from the optimal dynamic consumption equation (household's Euler equation).

These three equations formed a relatively simple model which could be

used for the theoretical analysis of policy issues. However, the model

was oversimplified in some respects (for example, there is no capital or

investment). Also, it does not perform well empirically.

2000s

In the new millennium there have been several advances in new Keynesian economics.

The introduction of imperfectly competitive labor markets

Whilst

the models of the 1990s focused on sticky prices in the output market,

in 2000 Christopher Erceg, Dale Henderson and Andrew Levin adopted the

Blanchard and Kiyotaki model of unionized labor markets by combining it

with the Calvo pricing approach and introduced it into a new Keynesian

DSGE model.

The development of complex DSGE models.

In

order to have models that worked well with the data and could be used

for policy simulations, quite complicated new Keynesian models were

developed with several features. Seminal papers were published by Frank

Smets and Rafael Wouters and also Lawrence J. Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum and Charles Evans The common features of these models included:

- habit persistence. The marginal utility of consumption depends on past consumption.

- Calvo pricing in both output and product markets, with indexation so that when wages and prices are not explicitly reset, they are updated for inflation.

- capital adjustment costs and variable capital utilization.

- new shocks

- demand shocks, which affect the marginal utility of consumption

- markup shocks that influence the desired markup of price over marginal cost.

- monetary policy is represented by a Taylor rule.

- Bayesian estimation methods.

Sticky information

The idea of Sticky information found in Fischer's model was later developed by Gregory Mankiw and Ricardo Reis.

This added a new feature to Fischer's model: there is a fixed

probability that you can replan your wages or prices each period. Using

quarterly data, they assumed a value of 25%: that is, each quarter 25%

of randomly chosen firms/unions can plan a trajectory of current and

future prices based on current information. Thus if we consider the

current period: 25% of prices will be based on the latest information

available; the rest on information that was available when they last

were able to replan their price trajectory. Mankiw and Reis found that

the model of sticky information provided a good way of explaining

inflation persistence.

Sticky information models do not have nominal rigidity: firms or

unions are free to choose different prices or wages for each period. It

is the information that is sticky, not the prices. Thus when a firm gets

lucky and can re-plan its current and future prices, it will choose a

trajectory of what it believes will be the optimal prices now and in the

future. In general, this will involve setting a different price every

period covered by the plan. This is at odds with the empirical evidence

on prices. There are now many studies of price rigidity in different countries: the United States, the Eurozone, the United Kingdom

and others. These studies all show that whilst there are some sectors

where prices change frequently, there are also other sectors where

prices remain fixed over time. The lack of sticky prices in the sticky

information model is inconsistent with the behavior of prices in most of

the economy. This has led to attempts to formulate a "dual stickiness"

model that combines sticky information with sticky prices.

Policy implications

New Keynesian economists agree with New Classical economists that in the long run, the classical dichotomy holds: changes in the money supply are neutral.

However, because prices are sticky in the New Keynesian model, an

increase in the money supply (or equivalently, a decrease in the

interest rate) does increase output and lower unemployment in the short

run. Furthermore, some New Keynesian models confirm the non-neutrality

of money under several conditions.

Nonetheless, New Keynesian economists do not advocate using

expansive monetary policy for short run gains in output and employment,

as it would raise inflationary expectations and thus store up problems

for the future. Instead, they advocate using monetary policy for stabilization.

That is, suddenly increasing the money supply just to produce a

temporary economic boom is not recommended as eliminating the increased

inflationary expectations will be impossible without producing a

recession.

However, when the economy is hit by some unexpected external

shock, it may be a good idea to offset the macroeconomic effects of the

shock with monetary policy. This is especially true if the unexpected

shock is one (like a fall in consumer confidence) which tends to lower

both output and inflation; in that case, expanding the money supply

(lowering interest rates) helps by increasing output while stabilizing

inflation and inflationary expectations.

Studies of optimal monetary policy in New Keynesian DSGE models have focused on interest rate rules (especially 'Taylor rules'), specifying how the central bank should adjust the nominal interest rate in response to changes in inflation and output. (More precisely, optimal rules usually react to changes in the output gap, rather than changes in output per se.)

In some simple New Keynesian DSGE models, it turns out that

stabilizing inflation suffices, because maintaining perfectly stable

inflation also stabilizes output and employment to the maximum degree

desirable. Blanchard and Galí have called this property the ‘divine

coincidence’.

However, they also show that in models with more than one market

imperfection (for example, frictions in adjusting the employment level,

as well as sticky prices), there is no longer a 'divine coincidence',

and instead there is a tradeoff between stabilizing inflation and

stabilizing employment.

Further, while some macroeconomists believe that New Keynesian models

are on the verge of being useful for quarter-to-quarter quantitative

policy advice, disagreement exists.

Recently, it was shown that the divine coincidence does not

necessarily hold in the non-linear form of the standard New-Keynesian

model.

This property would only hold if the monetary authority is set to keep

the inflation rate at exactly 0%. At any other desired target for the

inflation rate, there is an endogenous trade-off, even under the absence

real imperfections such as sticky wages, and the divine coincidence no

longer holds.

Relation to other macroeconomic schools

Over the years, a sequence of 'new' macroeconomic theories related to or opposed to Keynesianism have been influential. After World War II, Paul Samuelson used the term neoclassical synthesis to refer to the integration of Keynesian economics with neoclassical economics. The idea was that the government and the central bank would maintain rough full employment, so that neoclassical notions—centered on the axiom of the universality of scarcity—would apply. John Hicks' IS/LM model was central to the neoclassical synthesis.

Later work by economists such as James Tobin and Franco Modigliani involving more emphasis on the microfoundations of consumption and investment was sometimes called neo-Keynesianism. It is often contrasted with the post-Keynesianism of Paul Davidson, which emphasizes the role of fundamental uncertainty in economic life, especially concerning issues of private fixed investment.

New Keynesianism is a response to Robert Lucas and the new classical school. That school criticized the inconsistencies of Keynesianism in the light of the concept of "rational expectations". The new classicals combined a unique market-clearing equilibrium (at full employment)

with rational expectations. The New Keynesians use "microfoundations"

to demonstrate that price stickiness hinders markets from clearing.

Thus, the rational expectations-based equilibrium need not be unique.

Whereas the neoclassical synthesis hoped that fiscal and monetary policy would maintain full employment, the new classicals

assumed that price and wage adjustment would automatically attain this

situation in the short run. The new Keynesians, on the other hand, see

full employment as being automatically achieved only in the long run,

since prices are "sticky" in the short run. Government and central-bank

policies are needed because the "long run" may be very long.

Keynes'

stress on the importance of centralized coordination of macroeconomic

policies (e.g., monetary and fiscal stimulus) and of international

economic institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund

(IMF), and of the maintenance of a controlled trading system was

emphasized during the 2008 global financial and economic crisis. This

has been reflected in the work of IMF economists and of Donald Markwell.

![\pi _{{t}}=\beta E_{{t}}[\pi _{{t+1}}]+\kappa y_{{t}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0ef7dd57c38352c58215d6a0a3e102a4218956f6)

![\beta E_{{t}}[\pi _{{t+1}}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/665311ff5571a987a4e48a2435270b77aa595d37)

![\kappa ={\frac {h[1-(1-h)\beta ]}{1-h}}\gamma](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c91590f920d1dc4d17ea89f5ce58c14b50261a9a)