| Spanish flu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | Strains of the A/H1N1 |

| Location | Worldwide |

| First outbreak | Disputed |

| Date | spring 1918 – spring/summer 1919 |

| Confirmed cases | 500 million (estimate) |

Deaths

| 17–50+ million (estimate) |

The Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 flu pandemic, was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. Lasting about 15 months from spring 1918 (northern hemisphere) to early summer 1919, it infected 500 million people – about a third of the world's population at the time. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

To maintain morale, World War I censors minimized early reports of illness and mortality in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and the United States. Newspapers were free to report the epidemic's effects in neutral Spain, such as the grave illness of King Alfonso XIII, and these stories created a false impression of Spain as especially hard hit. This gave rise to the name "Spanish" flu. Historical and epidemiological data are inadequate to identify with certainty the pandemic's geographic origin, with varying views as to its location.

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, with a higher survival rate for those in between, but the Spanish flu pandemic resulted in a higher than expected mortality rate for young adults. Scientists offer several possible explanations for the high mortality rate of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Some analyses have shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a cytokine storm, which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults. In contrast, a 2007 analysis of medical journals from the period of the pandemic found that the viral infection was no more aggressive than previous influenza strains. Instead, malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene, all exacerbated by the recent war, promoted bacterial superinfection. This superinfection killed most of the victims, typically after a somewhat prolonged death bed.

The 1918 Spanish flu was the first of two pandemics caused by H1N1 influenza A virus; the second was the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

Etymology

Despite its name, historical and epidemiological data cannot identify the geographic origin of the Spanish flu.The origin of the "Spanish flu" name stems from the pandemic's spread to Spain from France in November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war, having remained neutral, and had not imposed wartime censorship. Newspapers were therefore free to report the epidemic's effects, such as the grave illness of King Alfonso XIII, and these widely-spread stories created a false impression of Spain as especially hard hit.

Nearly a century after the Spanish flu struck in 1918–1920, the World Health Organization (WHO) called on scientists, national authorities and the media to follow best practices in naming new human infectious diseases to minimize unnecessary negative effects on nations, economies and people. More modern terms for this virus include the "1918 influenza pandemic," the "1918 flu pandemic," or variations of these.

History

Hypotheses about the source

Europe

The major UK troop staging and hospital camp in Étaples in France has been theorized by virologist John Oxford as being at the center of the Spanish flu. His study found that in late 1916 the Étaples camp was hit by the onset of a new disease with high mortality that caused symptoms similar to the flu. According to Oxford, a similar outbreak occurred in March 1917 at army barracks in Aldershot, and military pathologists later recognized these early outbreaks as the same disease as the 1918 flu. The overcrowded camp and hospital was an ideal environment for the spread of a respiratory virus. The hospital treated thousands of victims of poison gas attacks, and other casualties of war, and 100,000 soldiers passed through the camp every day. It also was home to a piggery, and poultry was regularly brought in from surrounding villages to feed the camp. Oxford and his team postulated that a precursor virus, harbored in birds, mutated and then migrated to pigs kept near the front.A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found evidence that the 1918 virus had been circulating in the European armies for months and possibly years before the 1918 pandemic. Political scientist Andrew Price-Smith published data from the Austrian archives suggesting the influenza began in Austria in early 1917.

United States

Some have suggested that the epidemic originated in the United States. Historian Alfred W. Crosby stated in 2003 that the flu originated in Kansas, and popular author John M. Barry described a January 1918 outbreak in Haskell County, Kansas, as the point of origin in his 2004 article.A 2018 study of tissue slides and medical reports led by evolutionary biology professor Michael Worobey found evidence against the disease originating from Kansas, as those cases were milder and had fewer deaths compared to the infections in New York City in the same time period. The study did find evidence through phylogenetic analyses that the virus likely had a North American origin, though it was not conclusive. In addition, the haemagglutinin glycoproteins of the virus suggest that it originated long before 1918, and other studies suggest that the reassortment of the H1N1 virus likely occurred in or around 1915.

China

One of the few regions of the world seemingly less affected by the 1918 flu pandemic was China, where several studies have documented a comparatively mild flu season in 1918. (Although this is disputed due to lack of data during the Warlord Period). This has led to speculation that the 1918 flu pandemic originated in China, as the lower rates of flu mortality may be explained by the Chinese population's previously acquired immunity to the flu virus.In 1993, Claude Hannoun, the leading expert on the 1918 flu at the Pasteur Institute, asserted the precursor virus was likely to have come from China. It then mutated in the United States near Boston and from there spread to Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, the rest of Europe, and the rest of the world, with Allied soldiers and sailors as the main disseminators. Hannoun considered several alternative hypotheses of origin, such as Spain, Kansas, and Brest, as being possible, but not likely.

In 2014, historian Mark Humphries argued that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines might have been the source of the pandemic. Humphries, of the Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John's, based his conclusions on newly unearthed records. He found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.

A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found no evidence that the 1918 virus was imported to Europe via Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers and instead found evidence of its circulation in Europe before the pandemic. The 2016 study suggested that the low flu mortality rate (an estimated 1/1000) found among the Chinese and Southeast Asian workers in Europe meant that the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic could not have originated from those workers.

A 2018 study of tissue slides and medical reports led by evolutionary biology professor Michael Worobey found evidence against the disease being spread by Chinese workers, noting that workers entered Europe through other routes that did not result in detectable spread, making them unlikely to have been the original hosts.

Spread

As U.S. troops deployed en masse for the war effort in Europe, they carried the Spanish flu with them.

When an infected person sneezes or coughs, more than half a million virus particles can spread to those nearby. The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I

hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and

augmented mutation. The war may also have reduced people's resistance to

the virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by

malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks,

increasing their susceptibility.

A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of this flu was

increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for

soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease. Another was lies and denial by governments, leaving the population ill-prepared to handle the outbreaks.

In the United States, the disease was first observed in Haskell

County, Kansas, in January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to

warn the US Public Health Service's academic journal. On 4 March 1918, company cook Albert Gitchell, from Haskell County, reported sick at Fort Riley,

a US military facility that at the time was training American troops

during World War I, making him the first recorded victim of the flu. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York. Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticised.

In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France; in Freetown, Sierra Leone; and in the U.S., in September, at the Boston Navy Yard and Camp Devens (later renamed Fort Devens), about 30 miles west of Boston. Other U.S. military sites were soon afflicted, as were troops being transported to Europe. The Spanish flu also spread through Ireland, carried there by returning Irish soldiers.

Mortality

Around the globe

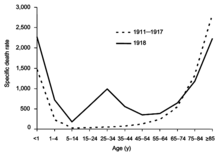

Difference

between the influenza mortality age-distributions of the 1918 epidemic

and normal epidemics – deaths per 100,000 persons in each age group,

United States, for the interpandemic years 1911–1917 (dashed line) and

the pandemic year 1918 (solid line)

Three pandemic waves: weekly combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, United Kingdom, 1918–1919

The Spanish flu infected around 500 million people, about one-third of the world's population. Estimates as to how many infected people died vary greatly, but the flu is regardless considered to be one of the deadliest pandemics in history.

An estimate from 1991 states that the virus killed between 25 and 39 million people.

A 2005 estimate put the death toll at 50 million (about 3% of the

global population), and possibly as high as 100 million (more than 5%). However, a reassessment in 2018 estimated the total to be about 17 million, though this has been contested. With a world population of 1.8 to 1.9 billion, these estimates correspond to between 1 and 6 percent of the population.

This flu killed more people in 24 weeks than HIV/AIDS killed in 24 years. However, it killed a much lower percentage of the world's population than the Black Death, which lasted for many more years.

The disease killed in many parts of the world. Some 12-17 million people died in India, about 5% of the population. The death toll in India's British-ruled districts was 13.88 million. Arnold (2019) estimates at least 12 million dead.

Estimates for the death toll in China have varied widely, a range which reflects the lack of centralised collection of health data at the time due to the Warlord period.

The first estimate of the Chinese death toll was made in 1991 by

Patterson and Pyle, which estimated China had a death toll of between 5

and 9 million. However, this 1991 study was subsequently criticized by

later studies due to flawed methodology, and newer studies have

published estimates of a far lower mortality rate in China.

For instance, Iijima in 1998 estimates the death toll in China to be

between 1 and 1.28 million based on data available from Chinese port

cities. As Wataru Iijima notes,

Patterson and Pyle in their study 'The 1918 Influenza Pandemic' tried to estimate the number of deaths by Spanish influenza in China as a whole. They argued that between 4.0 and 9.5 million people died in China, but this total was based purely on the assumption that the death rate there was 1.0–2.25 per cent in 1918, because China was a poor country similar to Indonesia and India where the mortality rate was of that order. Clearly their study was not based on any local Chinese statistical data.

The lower estimates of the Chinese death toll are based on the low

mortality rates that were found in Chinese port cities (for example,

Hong Kong) and on the assumption that poor communications prevented the

flu from penetrating the interior of China.

However, some contemporary newspaper and post office reports, as well

as reports from missionary doctors, suggest that the flu did penetrate

the Chinese interior and that influenza was severe in at least some

locations in the countryside of China.

In Japan, 23 million people were affected, with at least 390,000 reported deaths. In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died among 30 million inhabitants. In Tahiti, 13% of the population died during one month. Similarly, in Western Samoa 22% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.

In New Zealand, the flu killed an estimated 6,400 Pakeha and 2,500 indigenous Maori in six weeks, with Māori dying at eight times the rate of Pakeha.

In South Africa

it is estimated that about 300,000 people amounting to 6% of the

population died within six weeks. Government actions in the early stages

of the virus' arrival in the country in September 1918 are believed to

have unintentionally accelerated its spread throughout the country.

In Iran,

the mortality was very high: according to an estimate, between 902,400

and 2,431,000, or 8% to 22% of the total population died.

In the U.S., about 28% of the population of 105 million became

infected, and 500,000 to 850,000 died (0.48 to 0.81 percent of the

population). Native American tribes were particularly hard hit. In the Four Corners area, there were 3,293 registered deaths among Native Americans. Entire Inuit and Alaskan Native village communities died in Alaska. In Canada, 50,000 died.

In Brazil, 300,000 died, including president Rodrigues Alves. In Britain, as many as 250,000 died; in France, more than 400,000.

In Ghana, the influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people. Tafari Makonnen (the future Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia) was one of the first Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived. Many of his subjects did not; estimates for fatalities in the capital city, Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher. In British Somaliland, one official estimated that 7% of the native population died.

This huge death toll resulted from an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms. Symptoms in 1918 were unusual, initially causing influenza to be misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred". The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a common secondary infection associated with influenza. The virus also killed people directly by causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lungs.

Patterns of fatality

A nurse wears a cloth mask while treating a patient in Washington, DC

Seattle police wearing masks in December 1918

The pandemic mostly killed young adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of

pandemic influenza deaths in the U.S. occurred in people under 65, and

nearly half of deaths were in young adults 20 to 40 years old. In 1920,

the mortality rate among people under 65 had decreased sixfold to half

the mortality rate of people over 65, but 92% of deaths still occurred

in people under 65. This is unusual, since influenza is typically most deadly to weak individuals, such as infants under age two, adults over age 70, and the immunocompromised. In 1918, older adults may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the 1889–1890 flu pandemic, known as the "Russian flu".

According to historian John M. Barry, the most vulnerable of

all – "those most likely, of the most likely", to die – were pregnant

women. He reported that in thirteen studies of hospitalized women in the

pandemic, the death rate ranged from 23% to 71%.

Of the pregnant women who survived childbirth, over one-quarter (26%) lost the child.

Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.

Alberta's provincial board of health poster

Modern analysis has shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's immune system), which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults. One group of researchers recovered the virus from the bodies of frozen victims and transfected animals with it. The animals suffered rapidly progressive respiratory failure

and death through a cytokine storm. The strong immune reactions of

young adults were postulated to have ravaged the body, whereas the

weaker immune reactions of children and middle-aged adults resulted in

fewer deaths among those groups.

In fast-progressing cases, mortality was primarily from pneumonia, by virus-induced pulmonary consolidation. Slower-progressing cases featured secondary bacterial pneumonia, and possibly neural involvement that led to mental disorders in some cases. Some deaths resulted from malnourishment.

A study conducted by He et al. (2011) used a mechanistic

modeling approach to study the three waves of the 1918 influenza

pandemic. They examined the factors that underlie variability in

temporal patterns and their correlation to patterns of mortality and

morbidity. Their analysis suggests that temporal variations in

transmission rate provide the best explanation, and the variation in

transmission required to generate these three waves is within

biologically plausible values.

Another study by He et al. (2013) used a simple epidemic model

incorporating three factors to infer the cause of the three waves of

the 1918 influenza pandemic. These factors were school opening and

closing, temperature changes throughout the outbreak, and human

behavioral changes in response to the outbreak. Their modeling results

showed that all three factors are important, but human behavioral

responses showed the most significant effects.

A 2020 study found that US cities that implemented early and

extensive non-medical measures (quarantine etc.) suffered no additional

adverse economic effects due to implementing those measures, when compared with cities that implemented measures late or not at all.

Deadly second wave

American Expeditionary Force victims of the Spanish flu at U.S. Army Camp Hospital no. 45 in Aix-les-Bains, France, in 1918

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much more deadly than the

first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at

risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people

recovered easily. By August, when the second wave began in France,

Sierra Leone, and the United States,

the virus had mutated to a much more deadly form. October 1918 was the

month with the highest fatality rate of the whole pandemic.

This increased severity has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War. In civilian life, natural selection

favors a mild strain. Those who get very ill stay home, and those

mildly ill continue with their lives, preferentially spreading the mild

strain. In the trenches, natural selection was reversed. Soldiers with a

mild strain stayed where they were, while the severely ill were sent on

crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier

virus. The second wave began, and the flu quickly spread around the

world again. Consequently, during modern pandemics, health officials pay

attention when the virus reaches places with social upheaval (looking

for deadlier strains of the virus).

The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections had become immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu. This was most dramatically illustrated in Copenhagen,

which escaped with a combined mortality rate of just 0.29% (0.02% in

the first wave and 0.27% in the second wave) because of exposure to the

less-lethal first wave.

For the rest of the population, the second wave was far more deadly;

the most vulnerable people were those like the soldiers in the trenches –

adults who were young and fit.

Third wave 1919

In January 1919 a third wave of the Spanish Flu hit Australia, then

spread quickly through Europe and the United States, where it lingered

through the Spring and until June 1919. It primarily affected Spain, Serbia, Mexico and Great Britain, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

It was less severe than the second wave but still much more deadly than

the initial first wave. In the United States, isolated outbreaks

occurred in some cities including Los Angeles, New York City, Memphis, Nashville, San Francisco and St. Louis. Overall American mortality rates were in the tens of thousands during the first six months of 1919.

Fourth wave 1920

In spring 1920 a very minor fourth wave occurred in isolated areas including New York City, the United Kingdom, Austria, Scandinavia, and some South American islands. Mortality rates were very low.

Devastated communities

A chart of deaths from all causes in major cities, showing a peak in October and November 1918

Coromandel Hospital Board (New Zealand) advice to influenza sufferers (1918)

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many adults were

incapacitated that much of everyday life was hampered. Some communities

closed all stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There

were reports that healthcare workers could not tend the sick nor the

gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were

dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.

Several Pacific island

territories were hit particularly hard. The pandemic reached them from

New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent ships,

such as the SS Talune, carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand, the flu reached Tonga (killing 8% of the population), Nauru (16%), and Fiji (5%, 9,000 people).

Worst affected was Western Samoa, formerly German Samoa, which had been occupied by New Zealand in 1914. 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women, and 10% of children died. By contrast, Governor John Martin Poyer prevented the flu from reaching neighboring American Samoa by imposing a blockade. The disease spread fastest through the higher social classes among the indigenous peoples, because of the custom of gathering oral tradition from chiefs on their deathbeds; many community elders were infected through this process.

In New Zealand, 8,573 deaths were attributed to the 1918 pandemic

influenza, resulting in a total population fatality rate of 0.7%. Māori were 8 to 10 times as likely to die as other New Zealanders (Pakeha) because of their more crowded living conditions.

In Ireland, the Spanish flu accounted for 10% of the total deaths in 1918.

Less-affected areas

China may have experienced a relatively mild flu season in 1918 compared to other areas of the world.

However, there was no centralised collection of health statistics in

the country at the time, and some reports from its interior suggest that

mortality rates from influenza were perhaps higher in at least a few

locations in China in 1918.

However, at the very least, there is little evidence that China as a

whole was seriously affected by the flu compared to other countries in

the world.

Although medical records from China's interior are lacking, there was

extensive medical data recorded in Chinese port cities, such as then British-controlled Hong Kong, Canton, Peking, Harbin and Shanghai. This data was collected by the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, which was largely staffed by non-Chinese foreigners, such as the British, French, and other European colonial officials in China. As a whole, accurate data from China's port cities show astonishingly low mortality rates compared to other cities in Asia.

For example, the British authorities at Hong Kong and Canton reported a

mortality rate from influenza at a rate of 0.25% and 0.32%, much lower

than the reported mortality rate of other cities in Asia, such as Calcutta or Bombay, where influenza was much more devastating. Similarly, in the city of Shanghai – which had a population of over 2 million in 1918 – there were only 266 recorded deaths from influenza among the Chinese population in 1918. If extrapolated from the extensive data recorded from Chinese

cities, the suggested mortality rate from influenza in China as a whole

in 1918 was likely lower than 1% – much lower than the world average

(which was around 3–5%). In contrast, Japan and Taiwan

had reported a mortality rate from influenza around 0.45% and 0.69%

respectively, higher than the mortality rate collected from data in

Chinese port cities, such as Hong Kong (0.25%), Canton (0.32%), and

Shanghai.

1919 Tokyo, Japan

In Japan, 257,363 deaths were attributed to influenza by July 1919,

giving an estimated 0.4% mortality rate, much lower than nearly all

other Asian countries for which data are available. The Japanese

government severely restricted sea travel to and from the home islands

when the pandemic struck.

In the Pacific, American Samoa and the French colony of New Caledonia also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines. In Australia, nearly 12,000 perished.

By the end of the pandemic, the isolated island of Marajó, in Brazil's Amazon River Delta had not reported an outbreak. Saint Helena also reported no deaths.

The death toll in Russia has been estimated at 450,000, though the epidemiologists who suggested this number called it a "shot in the dark". If it is correct, Russia lost roughly 0.4% of its population, meaning it suffered the lowest influenza-related mortality in Europe. Another study considers this number unlikely, given that the country was in the grip of a civil war,

and the infrastructure of daily life had broken down; the study

suggests that Russia's death toll was closer to 2%, or 2.7 million

people.

Aspirin poisoning

In a 2009 paper published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, Karen Starko proposed that aspirin poisoning

contributed substantially to the fatalities. She based this on the

reported symptoms in those dying from the flu, as reported in the post mortem reports still available, and also the timing of the big "death spike" in October 1918. This occurred shortly after the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army and the Journal of the American Medical Association both recommended very large doses of 8 to 31 grams of aspirin per day as part of treatment. These levels will produce hyperventilation in 33% of patients, as well as lung edema in 3% of patients.

Starko also notes that many early deaths showed "wet", sometimes

hemorrhagic lungs, whereas late deaths showed bacterial pneumonia. She

suggests that the wave of aspirin poisonings was due to a "perfect storm" of events: Bayer's

patent on aspirin expired, so many companies rushed in to make a profit

and greatly increased the supply; this coincided with the Spanish flu;

and the symptoms of aspirin poisoning were not known at the time.

A street car conductor in Seattle in 1918 refusing to allow passengers aboard who are not wearing masks

As an explanation for the universally high mortality rate, this

hypothesis was questioned in a letter to the journal published in April

2010 by Andrew Noymer and Daisy Carreon of the University of California, Irvine,

and Niall Johnson of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in

Health Care. They questioned the universal applicability of the aspirin

theory, given the high mortality rate in countries such as India, where

there was little or no access to aspirin at the time, compared to the

death rate in places where aspirin was plentiful.

They concluded that "the salicylate

[aspirin] poisoning hypothesis [was] difficult to sustain as the

primary explanation for the unusual virulence of the 1918–1919 influenza

pandemic". In response, Starko said there was anecdotal evidence

of aspirin use in India and argued that even if aspirin

over-prescription had not contributed to the high Indian mortality rate,

it could still have been a factor for high rates in areas where other

exacerbating factors present in India played less of a role.

End of the pandemic

After the lethal second wave struck in late 1918, new cases dropped

abruptly – almost to nothing after the peak in the second wave.

In Philadelphia, for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending

16 October, but by 11 November, influenza had almost disappeared from

the city. One explanation for the rapid decline in the lethality of the

disease is that doctors became more effective in prevention and

treatment of the pneumonia that developed after the victims had

contracted the virus. However, John Barry stated in his 2004 book The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague In History that researchers have found no evidence to support this position. Some fatal cases did continue into March 1919, killing one player in the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals.

Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely

rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with

influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become

less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to

die out.

Long-term effects

A 2006 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that "cohorts in utero

during the pandemic displayed reduced educational attainment, increased

rates of physical disability, lower income, lower socioeconomic status,

and higher transfer payments received compared with other birth cohorts." A 2018 study found that the pandemic reduced educational attainment in populations.

The flu has been linked to the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.

Legacy

American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards set up inside Oakland Municipal Auditorium, 1918.

Academic Andrew Price-Smith has made the argument that the virus

helped tip the balance of power in the latter days of the war towards

the Allied cause. He provides data that the viral waves hit the Central Powers before the Allied powers and that both morbidity and mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.

Despite the high morbidity and mortality rates that resulted from

the epidemic, the Spanish flu began to fade from public awareness over

the decades until the arrival of news about bird flu and other pandemics in the 1990s and 2000s. This has led some historians to label the Spanish flu a "forgotten pandemic".

There are various theories of why the Spanish flu was

"forgotten". The rapid pace of the pandemic, which, for example, killed

most of its victims in the United States within less than nine months,

resulted in limited media coverage. The general population was familiar

with patterns of pandemic disease in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries: typhoid, yellow fever, diphtheria

and cholera all occurred near the same time. These outbreaks probably

lessened the significance of the influenza pandemic for the public. In some areas, the flu was not reported on, the only mention being that of advertisements for medicines claiming to cure it.

Additionally, the outbreak coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War.

Another explanation involves the age group affected by the disease. The

majority of fatalities, from both the war and the epidemic, were among

young adults. The number of war-related deaths of young adults may have

overshadowed the deaths caused by flu.

When people read the obituaries, they saw the war or postwar

deaths and the deaths from the influenza side by side. Particularly in

Europe, where the war's toll was high, the flu may not have had a

tremendous psychological impact or may have seemed an extension of the

war's tragedies.

The duration of the pandemic and the war could have also played a role.

The disease would usually only affect a particular area for a month

before leaving. The war, however, had initially been expected to end quickly but lasted for four years by the time the pandemic struck.

1918 influenza epidemic burial site in Auckland, New Zealand

With regard to global economic effects, many businesses in the

entertainment and service industries suffered losses in revenue, while

the healthcare industry reported profit gains.

Historian Nancy Bristow has argued that the pandemic, when combined with

the increasing number of women attending college, contributed to the

success of women in the field of nursing. This was due in part to the

failure of medical doctors, who were predominantly men, to contain and

prevent the illness. Nursing staff, who were mainly women, celebrated

the success of their patient care and did not associate the spread of

the disease with their work.

In Spain, sources from the period explicitly linked the Spanish flu to the cultural figure of Don Juan. The nickname for the flu, the "Naples Soldier", was adopted from Federico Romero and Guillermo Fernández Shaw's 1916 operetta, The Song of Forgetting (La canción del olvido). The protagonist of the operetta was a stock Don Juan type. Federico Romero, one of the librettists, quipped that the play's most popular musical number, Naples Soldier,

was as catchy as the flu. Davis argued the Spanish flu–Don Juan

connection allowed Spaniards to make sense of their epidemic experience

by interpreting it through their familiar Don Juan story.

Research

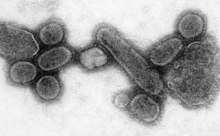

An electron micrograph showing recreated 1918 influenza virions

At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Terrence Tumpey examines a reconstructed version of the 1918 flu.

The origin of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the relationship between

the near-simultaneous outbreaks in humans and swine, have been

controversial. One hypothesis is that the virus strain originated at

Fort Riley, Kansas, in viruses in poultry and swine which the fort bred

for food; the soldiers were then sent from Fort Riley around the world,

where they spread the disease.

Similarities between a reconstruction of the virus and avian viruses,

combined with the human pandemic preceding the first reports of

influenza in swine, led researchers to conclude the influenza virus

jumped directly from birds to humans, and swine caught the disease from

humans.

Others have disagreed, and more recent research has suggested the strain may have originated in a nonhuman, mammalian species. An estimated date for its appearance in mammalian hosts has been put at the period 1882–1913. This ancestor virus diverged about 1913–1915 into two clades (or biological groups), which gave rise to the classical swine and human H1N1

influenza lineages. The last common ancestor of human strains dates to

between February 1917 and April 1918. Because pigs are more readily

infected with avian influenza viruses than are humans, they were

suggested as the original recipients of the virus, passing the virus to

humans sometime between 1913 and 1918.

An effort to recreate the 1918 flu strain (a subtype of avian strain H1N1) was a collaboration among the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the USDA ARS Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, and Mount Sinai School of Medicine

in New York City. The effort resulted in the announcement (on 5 October

2005) that the group had successfully determined the virus's genetic sequence, using historic tissue samples recovered by pathologist Johan Hultin from an Inuit female flu victim buried in the Alaskan permafrost and samples preserved from American soldiers Roscoe Vaughan and James Downs.

On 18 January 2007, Kobasa et al. (2007) reported that monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) infected with the recreated flu strain exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic, and died from cytokine storms –

an overreaction of the immune system. This may explain why the 1918 flu

had its surprising effect on younger, healthier people, as a person

with a stronger immune system would potentially have a stronger

overreaction.

On 16 September 2008, the body of British politician and diplomat Sir Mark Sykes was exhumed to study the RNA of the flu virus in efforts to understand the genetic structure of modern H5N1 bird flu. Sykes had been buried in 1919 in a lead coffin which scientists hoped had helped preserve the virus. The coffin was found to be split and the cadaver badly decomposed; nonetheless, samples of lung and brain tissue were taken.

In December 2008, research by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin linked the presence of three specific genes (termed PA, PB1, and PB2) and a nucleoprotein

derived from 1918 flu samples to the ability of the flu virus to invade

the lungs and cause pneumonia. The combination triggered similar

symptoms in animal testing.

In June 2010, a team at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported the 2009 flu pandemic vaccine provided some cross-protection against the 1918 flu pandemic strain.

One of the few things known for certain about the influenza in

1918 and for some years after was that it was, except in the laboratory,

exclusively a disease of human beings.

In 2013, the AIR Worldwide Research and Modeling Group

"characterized the historic 1918 pandemic and estimated the effects of a

similar pandemic occurring today using the AIR Pandemic Flu Model". In

the model, "a modern day 'Spanish flu' event would result in additional

life insurance losses of between US$15.3–27.8 billion in the United

States alone", with 188,000–337,000 deaths in the United States.

In 2018, Michael Worobey, an evolutionary biology professor at the University of Arizona who is examining the history of the 1918 pandemic, revealed that he obtained tissue slides created by William Rolland,

a physician who reported on a respiratory illness likely to be the

virus while a pathologist in the British military during World War One. Rolland had authored an article in the Lancet during 1917 about a respiratory illness outbreak beginning in 1916 in Étaples, France.

Worobey traced recent references to that article to family members who

had retained slides that Rolland had prepared during that time. Worobey

extracted tissue from the slides to potentially reveal more about the

origin of the pathogen.