Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interaction among rational decision-makers. It has applications in all fields of social science, as well as in logic, systems science and computer science. Originally, it addressed zero-sum games,

in which each participant's gains or losses are exactly balanced by

those of the other participants. Today, game theory applies to a wide

range of behavioral relations, and is now an umbrella term for the science of logical decision making in humans, animals, and computers.

Modern game theory began with the idea of mixed-strategy equilibria in two-person zero-sum games and its proof by John von Neumann. Von Neumann's original proof used the Brouwer fixed-point theorem on continuous mappings into compact convex sets, which became a standard method in game theory and mathematical economics. His paper was followed by the 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, co-written with Oskar Morgenstern, which considered cooperative games of several players. The second edition of this book provided an axiomatic theory of expected utility, which allowed mathematical statisticians and economists to treat decision-making under uncertainty.

Game theory was developed extensively in the 1950s by many scholars. It was explicitly applied to biology in the 1970s, although similar developments go back at least as far as the 1930s. Game theory has been widely recognized as an important tool in many fields. As of 2014, with the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences going to game theorist Jean Tirole, eleven game theorists have won the economics Nobel Prize. John Maynard Smith was awarded the Crafoord Prize for his application of game theory to biology.

Modern game theory began with the idea of mixed-strategy equilibria in two-person zero-sum games and its proof by John von Neumann. Von Neumann's original proof used the Brouwer fixed-point theorem on continuous mappings into compact convex sets, which became a standard method in game theory and mathematical economics. His paper was followed by the 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, co-written with Oskar Morgenstern, which considered cooperative games of several players. The second edition of this book provided an axiomatic theory of expected utility, which allowed mathematical statisticians and economists to treat decision-making under uncertainty.

Game theory was developed extensively in the 1950s by many scholars. It was explicitly applied to biology in the 1970s, although similar developments go back at least as far as the 1930s. Game theory has been widely recognized as an important tool in many fields. As of 2014, with the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences going to game theorist Jean Tirole, eleven game theorists have won the economics Nobel Prize. John Maynard Smith was awarded the Crafoord Prize for his application of game theory to biology.

History

Discussions of two-person games began long before the rise of modern, mathematical game theory.

The first known discussion of game theory occurred in a letter believed to be written in 1713 by Charles Waldegrave, an active Jacobite and uncle to James Waldegrave, a British diplomat.

The true identity of the original correspondent is somewhat elusive

given the limited details and evidence available and the subjective

nature of its interpretation. One theory postulates Francis Waldegrave

as the true correspondent, but this has yet to be proven. In this letter, Waldegrave provides a minimax mixed strategy solution to a two-person version of the card game le Her, and the problem is now known as Waldegrave problem. In his 1838 Recherches sur les principes mathématiques de la théorie des richesses (Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth), Antoine Augustin Cournot considered a duopoly and presents a solution that is the Nash equilibrium of the game.

In 1913, Ernst Zermelo published Über eine Anwendung der Mengenlehre auf die Theorie des Schachspiels (On an Application of Set Theory to the Theory of the Game of Chess), which proved that the optimal chess strategy is strictly determined. This paved the way for more general theorems.

In 1938, the Danish mathematical economist Frederik Zeuthen proved that the mathematical model had a winning strategy by using Brouwer's fixed point theorem. In his 1938 book Applications aux Jeux de Hasard and earlier notes, Émile Borel

proved a minimax theorem for two-person zero-sum matrix games only when

the pay-off matrix was symmetric and provides a solution to a

non-trivial infinite game (known in English as Blotto game). Borel conjectured the non-existence of mixed-strategy equilibria in finite two-person zero-sum games, a conjecture that was proved false by von Neumann.

Game theory did not really exist as a unique field until John von Neumann published the paper On the Theory of Games of Strategy in 1928. Von Neumann's original proof used Brouwer's fixed-point theorem on continuous mappings into compact convex sets, which became a standard method in game theory and mathematical economics. His paper was followed by his 1944 book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior co-authored with Oskar Morgenstern. The second edition of this book provided an axiomatic theory of utility, which reincarnated Daniel Bernoulli's

old theory of utility (of money) as an independent discipline. Von

Neumann's work in game theory culminated in this 1944 book. This

foundational work contains the method for finding mutually consistent

solutions for two-person zero-sum games. Subsequent work focused

primarily on cooperative game

theory, which analyzes optimal strategies for groups of individuals,

presuming that they can enforce agreements between them about proper

strategies.

In 1950, the first mathematical discussion of the prisoner's dilemma appeared, and an experiment was undertaken by notable mathematicians Merrill M. Flood and Melvin Dresher, as part of the RAND Corporation's investigations into game theory. RAND pursued the studies because of possible applications to global nuclear strategy. Around this same time, John Nash developed a criterion for mutual consistency of players' strategies known as the Nash equilibrium,

applicable to a wider variety of games than the criterion proposed by

von Neumann and Morgenstern. Nash proved that every finite n-player,

non-zero-sum (not just two-player zero-sum) non-cooperative game has what is now known as a Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies.

Game theory experienced a flurry of activity in the 1950s, during which the concepts of the core, the extensive form game, fictitious play, repeated games, and the Shapley value were developed. The 1950s also saw the first applications of game theory to philosophy and political science.

In 1979 Robert Axelrod

tried setting up computer programs as players and found that in

tournaments between them the winner was often a simple "tit-for-tat"

program--submitted by Anatol Rapoport--that

cooperates on the first step, then, on subsequent steps, does whatever

its opponent did on the previous step. The same winner was also often

obtained by natural selection; a fact that is widely taken to explain

cooperation phenomena in evolutionary biology and the social sciences.

Prize-winning achievements

In 1965, Reinhard Selten introduced his solution concept of subgame perfect equilibria, which further refined the Nash equilibrium. Later he would introduce trembling hand perfection as well. In 1994 Nash, Selten and Harsanyi became Economics Nobel Laureates for their contributions to economic game theory.

In the 1970s, game theory was extensively applied in biology, largely as a result of the work of John Maynard Smith and his evolutionarily stable strategy. In addition, the concepts of correlated equilibrium, trembling hand perfection, and common knowledge[a] were introduced and analyzed.

In 2005, game theorists Thomas Schelling and Robert Aumann followed Nash, Selten, and Harsanyi as Nobel Laureates. Schelling worked on dynamic models, early examples of evolutionary game theory.

Aumann contributed more to the equilibrium school, introducing

equilibrium coarsening and correlated equilibria, and developing an

extensive formal analysis of the assumption of common knowledge and of

its consequences.

In 2007, Leonid Hurwicz, Eric Maskin, and Roger Myerson were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics "for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory". Myerson's contributions include the notion of proper equilibrium, and an important graduate text: Game Theory, Analysis of Conflict.[1] Hurwicz introduced and formalized the concept of incentive compatibility.

In 2012, Alvin E. Roth and Lloyd S. Shapley

were awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics "for the theory of stable

allocations and the practice of market design". In 2014, the Nobel went to game theorist Jean Tirole.

Game types

Cooperative / non-cooperative

A game is cooperative if the players are able to form binding commitments externally enforced (e.g. through contract law). A game is non-cooperative if players cannot form alliances or if all agreements need to be self-enforcing (e.g. through credible threats).

Cooperative games are often analyzed through the framework of cooperative game theory,

which focuses on predicting which coalitions will form, the joint

actions that groups take, and the resulting collective payoffs. It is

opposed to the traditional non-cooperative game theory which focuses on predicting individual players' actions and payoffs and analyzing Nash equilibria.

Cooperative game theory provides a high-level approach as it

describes only the structure, strategies, and payoffs of coalitions,

whereas non-cooperative game theory also looks at how bargaining

procedures will affect the distribution of payoffs within each

coalition. As non-cooperative game theory is more general, cooperative

games can be analyzed through the approach of non-cooperative game

theory (the converse does not hold) provided that sufficient assumptions

are made to encompass all the possible strategies available to players

due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperation. While it

would thus be optimal to have all games expressed under a

non-cooperative framework, in many instances insufficient information is

available to accurately model the formal procedures available during

the strategic bargaining process, or the resulting model would be too

complex to offer a practical tool in the real world. In such cases,

cooperative game theory provides a simplified approach that allows

analysis of the game at large without having to make any assumption

about bargaining powers.

Symmetric / asymmetric

|

|

E | F |

| E | 1, 2 | 0, 0 |

| F | 0, 0 | 1, 2 |

| An asymmetric game | ||

A symmetric game is a game where the payoffs for playing a particular

strategy depend only on the other strategies employed, not on who is

playing them. That is, if the identities of the players can be changed

without changing the payoff to the strategies, then a game is symmetric.

Many of the commonly studied 2×2 games are symmetric. The standard

representations of chicken, the prisoner's dilemma, and the stag hunt are all symmetric games. Some

scholars would consider certain asymmetric games as examples of these

games as well. However, the most common payoffs for each of these games

are symmetric.

Most commonly studied asymmetric games are games where there are

not identical strategy sets for both players. For instance, the ultimatum game and similarly the dictator game

have different strategies for each player. It is possible, however, for

a game to have identical strategies for both players, yet be

asymmetric. For example, the game pictured to the right is asymmetric

despite having identical strategy sets for both players.

Zero-sum / non-zero-sum

| A | B | |

| A | –1, 1 | 3, –3 |

| B | 0, 0 | –2, 2 |

| A zero-sum game | ||

Zero-sum games are a special case of constant-sum games in which

choices by players can neither increase nor decrease the available

resources. In zero-sum games, the total benefit to all players in the

game, for every combination of strategies, always adds to zero (more

informally, a player benefits only at the equal expense of others). Poker

exemplifies a zero-sum game (ignoring the possibility of the house's

cut), because one wins exactly the amount one's opponents lose. Other

zero-sum games include matching pennies and most classical board games including Go and chess.

Many games studied by game theorists (including the famed prisoner's dilemma) are non-zero-sum games, because the outcome

has net results greater or less than zero. Informally, in non-zero-sum

games, a gain by one player does not necessarily correspond with a loss

by another.

Constant-sum games correspond to activities like theft and

gambling, but not to the fundamental economic situation in which there

are potential gains from trade.

It is possible to transform any game into a (possibly asymmetric)

zero-sum game by adding a dummy player (often called "the board") whose

losses compensate the players' net winnings.

Simultaneous / sequential

Simultaneous games

are games where both players move simultaneously, or if they do not

move simultaneously, the later players are unaware of the earlier

players' actions (making them effectively simultaneous). Sequential games (or dynamic games) are games where later players have some knowledge about earlier actions. This need not be perfect information

about every action of earlier players; it might be very little

knowledge. For instance, a player may know that an earlier player did

not perform one particular action, while s/he does not know which of the

other available actions the first player actually performed.

The difference between simultaneous and sequential games is captured in the different representations discussed above. Often, normal form is used to represent simultaneous games, while extensive form

is used to represent sequential ones. The transformation of extensive

to normal form is one way, meaning that multiple extensive form games

correspond to the same normal form. Consequently, notions of equilibrium

for simultaneous games are insufficient for reasoning about sequential

games; see subgame perfection.

In short, the differences between sequential and simultaneous games are as follows:

| Sequential | Simultaneous | |

|---|---|---|

| Normally denoted by | Decision trees | Payoff matrices |

Prior knowledge

of opponent's move? |

Yes | No |

| Time axis? | Yes | No |

| Also known as |

Extensive-form game

Extensive game |

Strategy game

Strategic game |

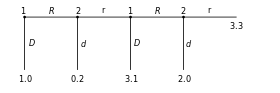

Perfect information and imperfect information

A game of imperfect information (the dotted line represents ignorance on the part of player 2, formally called an information set)

An important subset of sequential games consists of games of perfect information.

A game is one of perfect information if all players know the moves

previously made by all other players. Most games studied in game theory

are imperfect-information games. Examples of perfect-information games include tic-tac-toe, checkers, infinite chess, and Go.

Many card games are games of imperfect information, such as poker and bridge. Perfect information is often confused with complete information, which is a similar concept.

Complete information requires that every player know the strategies and

payoffs available to the other players but not necessarily the actions

taken. Games of incomplete information can be reduced, however, to games of imperfect information by introducing "moves by nature".

Combinatorial games

Games

in which the difficulty of finding an optimal strategy stems from the

multiplicity of possible moves are called combinatorial games. Examples

include chess and go. Games that involve imperfect information may also have a strong combinatorial character, for instance backgammon.

There is no unified theory addressing combinatorial elements in games.

There are, however, mathematical tools that can solve particular

problems and answer general questions.

Games of perfect information have been studied in combinatorial game theory, which has developed novel representations, e.g. surreal numbers, as well as combinatorial and algebraic (and sometimes non-constructive) proof methods to solve games

of certain types, including "loopy" games that may result in infinitely

long sequences of moves. These methods address games with higher

combinatorial complexity than those usually considered in traditional

(or "economic") game theory. A typical game that has been solved this way is Hex. A related field of study, drawing from computational complexity theory, is game complexity, which is concerned with estimating the computational difficulty of finding optimal strategies.

Research in artificial intelligence

has addressed both perfect and imperfect information games that have

very complex combinatorial structures (like chess, go, or backgammon)

for which no provable optimal strategies have been found. The practical

solutions involve computational heuristics, like alpha–beta pruning or use of artificial neural networks trained by reinforcement learning, which make games more tractable in computing practice.

Infinitely long games

Games, as studied by economists and real-world game players, are

generally finished in finitely many moves. Pure mathematicians are not

so constrained, and set theorists in particular study games that last for infinitely many moves, with the winner (or other payoff) not known until after all those moves are completed.

The focus of attention is usually not so much on the best way to play such a game, but whether one player has a winning strategy. (It can be proven, using the axiom of choice, that there are games – even with perfect information and where the only outcomes are "win" or "lose" – for which neither player has a winning strategy.) The existence of such strategies, for cleverly designed games, has important consequences in descriptive set theory.

Discrete and continuous games

Much

of game theory is concerned with finite, discrete games that have a

finite number of players, moves, events, outcomes, etc. Many concepts

can be extended, however. Continuous games allow players to choose a strategy from a continuous strategy set. For instance, Cournot competition is typically modeled with players' strategies being any non-negative quantities, including fractional quantities.

Differential games

Differential games such as the continuous pursuit and evasion game are continuous games where the evolution of the players' state variables is governed by differential equations. The problem of finding an optimal strategy in a differential game is closely related to the optimal control theory. In particular, there are two types of strategies: the open-loop strategies are found using the Pontryagin maximum principle while the closed-loop strategies are found using Bellman's Dynamic Programming method.

A particular case of differential games are the games with a random time horizon. In such games, the terminal time is a random variable with a given probability distribution function. Therefore, the players maximize the mathematical expectation

of the cost function. It was shown that the modified optimization

problem can be reformulated as a discounted differential game over an

infinite time interval.

Evolutionary game theory

Evolutionary game theory studies players who adjust their strategies over time according to rules that are not necessarily rational or farsighted. In general, the evolution of strategies over time according to such rules is modeled as a Markov chain

with a state variable such as the current strategy profile or how the

game has been played in the recent past. Such rules may feature

imitation, optimization, or survival of the fittest.

In biology, such models can represent (biological) evolution,

in which offspring adopt their parents' strategies and parents who play

more successful strategies (i.e. corresponding to higher payoffs) have a

greater number of offspring. In the social sciences, such models

typically represent strategic adjustment by players who play a game many

times within their lifetime and, consciously or unconsciously,

occasionally adjust their strategies.

Stochastic outcomes (and relation to other fields)

Individual

decision problems with stochastic outcomes are sometimes considered

"one-player games". These situations are not considered game theoretical

by some authors. They may be modeled using similar tools within the related disciplines of decision theory, operations research, and areas of artificial intelligence, particularly AI planning (with uncertainty) and multi-agent system. Although these fields may have different motivators, the mathematics involved are substantially the same, e.g. using Markov decision processes (MDP).

Stochastic outcomes can also be modeled in terms of game theory by adding a randomly acting player who makes "chance moves" ("moves by nature").

This player is not typically considered a third player in what is

otherwise a two-player game, but merely serves to provide a roll of the

dice where required by the game.

For some problems, different approaches to modeling stochastic

outcomes may lead to different solutions. For example, the difference in

approach between MDPs and the minimax solution

is that the latter considers the worst-case over a set of adversarial

moves, rather than reasoning in expectation about these moves given a

fixed probability distribution. The minimax approach may be advantageous

where stochastic models of uncertainty are not available, but may also

be overestimating extremely unlikely (but costly) events, dramatically

swaying the strategy in such scenarios if it is assumed that an

adversary can force such an event to happen. (See Black swan theory

for more discussion on this kind of modeling issue, particularly as it

relates to predicting and limiting losses in investment banking.)

General models that include all elements of stochastic outcomes,

adversaries, and partial or noisy observability (of moves by other

players) have also been studied. The "gold standard" is considered to be partially observable stochastic game (POSG), but few realistic problems are computationally feasible in POSG representation.

Metagames

These are games the play of which is the development of the rules for another game, the target or subject game. Metagames seek to maximize the utility value of the rule set developed. The theory of metagames is related to mechanism design theory.

The term metagame analysis is also used to refer to a practical approach developed by Nigel Howard.

whereby a situation is framed as a strategic game in which stakeholders

try to realize their objectives by means of the options available to

them. Subsequent developments have led to the formulation of confrontation analysis.

Pooling games

These

are games prevailing over all forms of society. Pooling games are

repeated plays with changing payoff table in general over an experienced

path, and their equilibrium strategies usually take a form of

evolutionary social convention and economic convention. Pooling game

theory emerges to formally recognize the interaction between optimal

choice in one play and the emergence of forthcoming payoff table update

path, identify the invariance existence and robustness, and predict

variance over time. The theory is based upon topological transformation

classification of payoff table update over time to predict variance and

invariance, and is also within the jurisdiction of the computational law

of reachable optimality for ordered system.

Mean field game theory

Mean field game theory

is the study of strategic decision making in very large populations of

small interacting agents. This class of problems was considered in the

economics literature by Boyan Jovanovic and Robert W. Rosenthal, in the engineering literature by Peter E. Caines, and by mathematician Pierre-Louis Lions and Jean-Michel Lasry.

Representation of games

The

games studied in game theory are well-defined mathematical objects. To

be fully defined, a game must specify the following elements: the players of the game, the information and actions available to each player at each decision point, and the payoffs for each outcome. (Eric Rasmusen refers to these four "essential elements" by the acronym "PAPI".) A game theorist typically uses these elements, along with a solution concept of their choosing, to deduce a set of equilibrium strategies

for each player such that, when these strategies are employed, no

player can profit by unilaterally deviating from their strategy. These

equilibrium strategies determine an equilibrium to the game—a stable state in which either one outcome occurs or a set of outcomes occur with known probability.

Most cooperative games are presented in the characteristic

function form, while the extensive and the normal forms are used to

define noncooperative games.

Extensive form

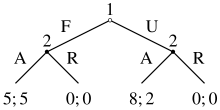

An extensive form game

The extensive form can be used to formalize games with a time sequencing of moves. Games here are played on trees (as pictured here). Here each vertex

(or node) represents a point of choice for a player. The player is

specified by a number listed by the vertex. The lines out of the vertex

represent a possible action for that player. The payoffs are specified

at the bottom of the tree. The extensive form can be viewed as a

multi-player generalization of a decision tree. To solve any extensive form game, backward induction

must be used. It involves working backward up the game tree to

determine what a rational player would do at the last vertex of the

tree, what the player with the previous move would do given that the

player with the last move is rational, and so on until the first vertex

of the tree is reached.

The game pictured consists of two players. The way this

particular game is structured (i.e., with sequential decision making and

perfect information), Player 1 "moves" first by choosing either F or U (fair or unfair). Next in the sequence, Player 2, who has now seen Player 1's move, chooses to play either A or R. Once Player 2 has made their choice, the game is considered finished and each player gets their respective payoff. Suppose that Player 1 chooses U and then Player 2 chooses A: Player 1

then gets a payoff of "eight" (which in real-world terms can be

interpreted in many ways, the simplest of which is in terms of money but

could mean things such as eight days of vacation or eight countries

conquered or even eight more opportunities to play the same game against

other players) and Player 2 gets a payoff of "two".

The extensive form can also capture simultaneous-move games and

games with imperfect information. To represent it, either a dotted line

connects different vertices to represent them as being part of the same

information set (i.e. the players do not know at which point they are),

or a closed line is drawn around them.

Normal form

| Player 2 chooses Left |

Player 2 chooses Right | |

| Player 1 chooses Up |

4, 3 | –1, –1 |

| Player 1 chooses Down |

0, 0 | 3, 4 |

| Normal form or payoff matrix of a 2-player, 2-strategy game | ||

The normal (or strategic form) game is usually represented by a matrix

which shows the players, strategies, and payoffs (see the example to

the right). More generally it can be represented by any function that

associates a payoff for each player with every possible combination of

actions. In the accompanying example there are two players; one chooses

the row and the other chooses the column. Each player has two

strategies, which are specified by the number of rows and the number of

columns. The payoffs are provided in the interior. The first number is

the payoff received by the row player (Player 1 in our example); the

second is the payoff for the column player (Player 2 in our example).

Suppose that Player 1 plays Up and that Player 2 plays Left. Then Player 1 gets a payoff of 4, and Player 2 gets 3.

When a game is presented in normal form, it is presumed that each

player acts simultaneously or, at least, without knowing the actions of

the other. If players have some information about the choices of other

players, the game is usually presented in extensive form.

Every extensive-form game has an equivalent normal-form game,

however the transformation to normal form may result in an exponential

blowup in the size of the representation, making it computationally

impractical.

Characteristic function form

In games that possess removable utility, separate rewards are not

given; rather, the characteristic function decides the payoff of each

unity. The idea is that the unity that is 'empty', so to speak, does not

receive a reward at all.

The origin of this form is to be found in John von Neumann and

Oskar Morgenstern's book; when looking at these instances, they guessed

that when a union appears, it works against the fraction

as if two individuals were playing a normal game. The balanced payoff of

C is a basic function. Although there are differing examples that help

determine coalitional amounts from normal games, not all appear that in

their function form can be derived from such.

Formally, a characteristic function is seen as: (N,v), where N represents the group of people and is a normal utility.

Such characteristic functions have expanded to describe games where there is no removable utility.

Alternative game representations

Alternative game representation forms exist and are used for some

subclasses of games or adjusted to the needs of interdisciplinary

research. In addition to classical game representions, some of the alternative representations also encode time related aspects.

| Name | Year | Means | Type of games | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congestion game [43] | 1973 | functions | subset of n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

| Sequential form[44] | 1994 | matrices | 2-person games of imperfect information | No |

| Timed games[45][46] | 1994 | functions | 2-person games | Yes |

| Gala[47] | 1997 | logic | n-person games of imperfect information | No |

| Local effect games[48] | 2003 | functions | subset of n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

| GDL[49] | 2005 | logic | deterministic n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

| Game Petri-nets[50] | 2006 | Petri net | deterministic n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

| Continuous games[51] | 2007 | functions | subset of 2-person games of imperfect information | Yes |

| PNSI[52][53] | 2008 | Petri net | n-person games of imperfect information | Yes |

| Action graph games[54] | 2012 | graphs, functions | n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

| Graphical games[55] | 2015 | graphs, functions | n-person games, simultaneous moves | No |

General and applied uses

As a method of applied mathematics, game theory has been used to study a wide variety of human and animal behaviors. It was initially developed in economics

to understand a large collection of economic behaviors, including

behaviors of firms, markets, and consumers. The first use of

game-theoretic analysis was by Antoine Augustin Cournot in 1838 with his solution of the Cournot duopoly.

The use of game theory in the social sciences has expanded, and game

theory has been applied to political, sociological, and psychological

behaviors as well.

Although pre-twentieth century naturalists such as Charles Darwin made game-theoretic kinds of statements, the use of game-theoretic analysis in biology began with Ronald Fisher's

studies of animal behavior during the 1930s. This work predates the

name "game theory", but it shares many important features with this

field. The developments in economics were later applied to biology

largely by John Maynard Smith in his book Evolution and the Theory of Games.

In addition to being used to describe, predict, and explain

behavior, game theory has also been used to develop theories of ethical

or normative behavior and to prescribe such behavior. In economics and philosophy,

scholars have applied game theory to help in the understanding of good

or proper behavior. Game-theoretic arguments of this type can be found

as far back as Plato. An alternative version of game theory, called chemical game theory, represents the player's choices as metaphorical chemical reactant molecules called “knowlecules”. Chemical game theory then calculates the outcomes as equilibrium solutions to a system of chemical reactions.

Description and modeling

A four-stage centipede game

The primary use of game theory is to describe and model how human populations behave. Some

scholars believe that by finding the equilibria of games they can

predict how actual human populations will behave when confronted with

situations analogous to the game being studied. This particular view of

game theory has been criticized. It is argued that the assumptions made

by game theorists are often violated when applied to real-world

situations. Game theorists usually assume players act rationally, but in

practice human behavior often deviates from this model. Game theorists

respond by comparing their assumptions to those used in physics. Thus while their assumptions do not always hold, they can treat game theory as a reasonable scientific ideal akin to the models used by physicists. However, empirical work has shown that in some classic games, such as the centipede game, guess 2/3 of the average game, and the dictator game,

people regularly do not play Nash equilibria. There is an ongoing

debate regarding the importance of these experiments and whether the

analysis of the experiments fully captures all aspects of the relevant

situation.

Some game theorists, following the work of John Maynard Smith and George R. Price, have turned to evolutionary game theory in order to resolve these issues. These models presume either no rationality or bounded rationality on the part of players. Despite the name, evolutionary game theory does not necessarily presume natural selection

in the biological sense. Evolutionary game theory includes both

biological as well as cultural evolution and also models of individual

learning (for example, fictitious play dynamics).

Prescriptive or normative analysis

| Cooperate | Defect | |

| Cooperate | -1, -1 | -10, 0 |

| Defect | 0, -10 | -5, -5 |

| The Prisoner's Dilemma | ||

Some scholars see game theory not as a predictive tool for the

behavior of human beings, but as a suggestion for how people ought to

behave. Since a strategy, corresponding to a Nash equilibrium of a game constitutes one's best response

to the actions of the other players – provided they are in (the same)

Nash equilibrium – playing a strategy that is part of a Nash equilibrium

seems appropriate. This normative use of game theory has also come

under criticism.

Economics and business

Game theory is a major method used in mathematical economics and business for modeling competing behaviors of interacting agents. Applications include a wide array of economic phenomena and approaches, such as auctions, bargaining, mergers and acquisitions pricing, fair division, duopolies, oligopolies, social network formation, agent-based computational economics, general equilibrium, mechanism design, and voting systems; and across such broad areas as experimental economics, behavioral economics, information economics, industrial organization, and political economy.

This research usually focuses on particular sets of strategies known as "solution concepts" or "equilibria". A common assumption is that players act rationally. In non-cooperative games, the most famous of these is the Nash equilibrium.

A set of strategies is a Nash equilibrium if each represents a best

response to the other strategies. If all the players are playing the

strategies in a Nash equilibrium, they have no unilateral incentive to

deviate, since their strategy is the best they can do given what others

are doing.

The payoffs of the game are generally taken to represent the utility of individual players.

A prototypical paper on game theory in economics begins by

presenting a game that is an abstraction of a particular economic

situation. One or more solution concepts are chosen, and the author

demonstrates which strategy sets in the presented game are equilibria of

the appropriate type. Naturally one might wonder to what use this

information should be put. Economists and business professors suggest

two primary uses (noted above): descriptive and prescriptive.

Project management

Sensible

decision-making is critical for the success of projects. In project

management, game theory is used to model the decision-making process of

players, such as investors, project managers, contractors,

sub-contractors, governments and customers. Quite often, these players

have competing interests, and sometimes their interests are directly

detrimental to other players, making project management scenarios

well-suited to be modeled by game theory.

Piraveenan (2019)

in his review provides several examples where game theory is used to

model project management scenarios. For instance, an investor typically

has several investment options, and each option will likely result in a

different project, and thus one of the investment options has to be

chosen before the project charter can be produced. Similarly, any large

project involving subcontractors, for instance, a construction project,

has a complex interplay between the main contractor (the project

manager) and subcontractors, or among the subcontractors themselves,

which typically has several decision points. For example, if there is an

ambiguity in the contract between the contractor and subcontractor,

each must decide how hard to push their case without jeopardizing the

whole project, and thus their own stake in it. Similarly, when projects

from competing organizations are launched, the marketing personnel have

to decide what is the best timing and strategy to market the project, or

its resultant product or service, so that it can gain maximum traction

in the face of competition. In each of these scenarios, the required

decisions depend on the decisions of other players who, in some way,

have competing interests to the interests of the decision-maker, and

thus can ideally be modeled using game theory.

Piraveenan

summarises that two-player games are predominantly used to model

project management scenarios, and based on the identity of these

players, five distinct types of games are used in project management.

- Government-sector–private-sector games (games that model public–private partnerships)

- Contractor–contractor games

- Contractor–subcontractor games

- Subcontractor–subcontractor games

- Games involving other players

In terms of types of games, both cooperative as well as

non-cooperative games, normal-form as well as extensive-form games, and

zero-sum as well as non-zero-sum games are used to model various project

management scenarios.

Political science

The application of game theory to political science is focused in the overlapping areas of fair division, political economy, public choice, war bargaining, positive political theory, and social choice theory.

In each of these areas, researchers have developed game-theoretic

models in which the players are often voters, states, special interest

groups, and politicians.

Early examples of game theory applied to political science are provided by Anthony Downs. In his book An Economic Theory of Democracy, he applies the Hotelling firm location model

to the political process. In the Downsian model, political candidates

commit to ideologies on a one-dimensional policy space. Downs first

shows how the political candidates will converge to the ideology

preferred by the median voter if voters are fully informed, but then

argues that voters choose to remain rationally ignorant which allows for

candidate divergence. Game Theory was applied in 1962 to the Cuban missile crisis during the presidency of John F. Kennedy.

It has also been proposed that game theory explains the stability

of any form of political government. Taking the simplest case of a

monarchy, for example, the king, being only one person, does not and

cannot maintain his authority by personally exercising physical control

over all or even any significant number of his subjects. Sovereign

control is instead explained by the recognition by each citizen that all

other citizens expect each other to view the king (or other established

government) as the person whose orders will be followed. Coordinating

communication among citizens to replace the sovereign is effectively

barred, since conspiracy to replace the sovereign is generally

punishable as a crime. Thus, in a process that can be modeled by

variants of the prisoner's dilemma,

during periods of stability no citizen will find it rational to move to

replace the sovereign, even if all the citizens know they would be

better off if they were all to act collectively.

A game-theoretic explanation for democratic peace

is that public and open debate in democracies sends clear and reliable

information regarding their intentions to other states. In contrast, it

is difficult to know the intentions of nondemocratic leaders, what

effect concessions will have, and if promises will be kept. Thus there

will be mistrust and unwillingness to make concessions if at least one

of the parties in a dispute is a non-democracy.

On the other hand, game theory predicts that two countries may

still go to war even if their leaders are cognizant of the costs of

fighting. War may result from asymmetric information; two countries may

have incentives to mis-represent the amount of military resources they

have on hand, rendering them unable to settle disputes agreeably without

resorting to fighting. Moreover, war may arise because of commitment

problems: if two countries wish to settle a dispute via peaceful means,

but each wishes to go back on the terms of that settlement, they may

have no choice but to resort to warfare. Finally, war may result from

issue indivisibilities.

Game theory could also help predict a nation's responses when

there is a new rule or law to be applied to that nation. One example

would be Peter John Wood's (2013) research when he looked into what

nations could do to help reduce climate change. Wood thought this could

be accomplished by making treaties with other nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, he concluded that this idea could not work because it would create a prisoner's dilemma to the nations.

Biology

| Hawk | Dove | |

| Hawk | 20, 20 | 80, 40 |

| Dove | 40, 80 | 60, 60 |

| The hawk-dove game | ||

Unlike those in economics, the payoffs for games in biology are often interpreted as corresponding to fitness. In addition, the focus has been less on equilibria that correspond to a notion of rationality and more on ones that would be maintained by evolutionary forces. The best-known equilibrium in biology is known as the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), first introduced in (Maynard Smith & Price 1973). Although its initial motivation did not involve any of the mental requirements of the Nash equilibrium, every ESS is a Nash equilibrium.

In biology, game theory has been used as a model to understand

many different phenomena. It was first used to explain the evolution

(and stability) of the approximate 1:1 sex ratios. (Fisher 1930)

suggested that the 1:1 sex ratios are a result of evolutionary forces

acting on individuals who could be seen as trying to maximize their

number of grandchildren.

Additionally, biologists have used evolutionary game theory and the ESS to explain the emergence of animal communication. The analysis of signaling games and other communication games has provided insight into the evolution of communication among animals. For example, the mobbing behavior

of many species, in which a large number of prey animals attack a

larger predator, seems to be an example of spontaneous emergent

organization. Ants have also been shown to exhibit feed-forward behavior

akin to fashion.

Biologists have used the game of chicken to analyze fighting behavior and territoriality.

According to Maynard Smith, in the preface to Evolution and the Theory of Games,

"paradoxically, it has turned out that game theory is more readily

applied to biology than to the field of economic behaviour for which it

was originally designed". Evolutionary game theory has been used to

explain many seemingly incongruous phenomena in nature.

One such phenomenon is known as biological altruism.

This is a situation in which an organism appears to act in a way that

benefits other organisms and is detrimental to itself. This is distinct

from traditional notions of altruism because such actions are not

conscious, but appear to be evolutionary adaptations to increase overall

fitness. Examples can be found in species ranging from vampire bats

that regurgitate blood they have obtained from a night's hunting and

give it to group members who have failed to feed, to worker bees that

care for the queen bee for their entire lives and never mate, to vervet monkeys that warn group members of a predator's approach, even when it endangers that individual's chance of survival. All of these actions increase the overall fitness of a group, but occur at a cost to the individual.

Evolutionary game theory explains this altruism with the idea of kin selection. Altruists discriminate between the individuals they help and favor relatives. Hamilton's rule explains the evolutionary rationale behind this selection with the equation c < b × r, where the cost c to the altruist must be less than the benefit b to the recipient multiplied by the coefficient of relatedness r.

The more closely related two organisms are causes the incidences of

altruism to increase because they share many of the same alleles. This

means that the altruistic individual, by ensuring that the alleles of

its close relative are passed on through survival of its offspring, can

forgo the option of having offspring itself because the same number of

alleles are passed on. For example, helping a sibling (in diploid

animals) has a coefficient of 1⁄2,

because (on average) an individual shares half of the alleles in its

sibling's offspring. Ensuring that enough of a sibling's offspring

survive to adulthood precludes the necessity of the altruistic

individual producing offspring.

The coefficient values depend heavily on the scope of the playing

field; for example if the choice of whom to favor includes all genetic

living things, not just all relatives, we assume the discrepancy between

all humans only accounts for approximately 1% of the diversity in the

playing field, a coefficient that was 1⁄2

in the smaller field becomes 0.995. Similarly if it is considered that

information other than that of a genetic nature (e.g. epigenetics,

religion, science, etc.) persisted through time the playing field

becomes larger still, and the discrepancies smaller.

Computer science and logic

Game theory has come to play an increasingly important role in logic and in computer science. Several logical theories have a basis in game semantics. In addition, computer scientists have used games to model interactive computations. Also, game theory provides a theoretical basis to the field of multi-agent systems.

Separately, game theory has played a role in online algorithms; in particular, the k-server problem, which has in the past been referred to as games with moving costs and request-answer games. Yao's principle is a game-theoretic technique for proving lower bounds on the computational complexity of randomized algorithms, especially online algorithms.

The emergence of the Internet has motivated the development of

algorithms for finding equilibria in games, markets, computational

auctions, peer-to-peer systems, and security and information markets. Algorithmic game theory and within it algorithmic mechanism design combine computational algorithm design and analysis of complex systems with economic theory.

Philosophy

| Stag | Hare | |

| Stag | 3, 3 | 0, 2 |

| Hare | 2, 0 | 2, 2 |

| Stag hunt | ||

Game theory has been put to several uses in philosophy. Responding to two papers by W.V.O. Quine (1960, 1967), Lewis (1969) used game theory to develop a philosophical account of convention. In so doing, he provided the first analysis of common knowledge and employed it in analyzing play in coordination games. In addition, he first suggested that one can understand meaning in terms of signaling games. This later suggestion has been pursued by several philosophers since Lewis. Following Lewis (1969) game-theoretic account of conventions, Edna Ullmann-Margalit (1977) and Bicchieri (2006) have developed theories of social norms that define them as Nash equilibria that result from transforming a mixed-motive game into a coordination game.

Game theory has also challenged philosophers to think in terms of interactive epistemology:

what it means for a collective to have common beliefs or knowledge, and

what are the consequences of this knowledge for the social outcomes

resulting from the interactions of agents. Philosophers who have worked

in this area include Bicchieri (1989, 1993), Skyrms (1990), and Stalnaker (1999).

In ethics, some (most notably David Gauthier, Gregory Kavka, and Jean Hampton) authors have attempted to pursue Thomas Hobbes' project of deriving morality from self-interest. Since games like the prisoner's dilemma

present an apparent conflict between morality and self-interest,

explaining why cooperation is required by self-interest is an important

component of this project. This general strategy is a component of the

general social contract view in political philosophy (for examples, see Gauthier (1986) and Kavka (1986)).

Other authors have attempted to use evolutionary game theory

in order to explain the emergence of human attitudes about morality and

corresponding animal behaviors. These authors look at several games

including the prisoner's dilemma, stag hunt, and the Nash bargaining game as providing an explanation for the emergence of attitudes about morality (see, e.g., Skyrms (1996, 2004) and Sober and Wilson (1998)).

Retail and consumer product pricing

Game

theory applications are used heavily in the pricing strategies of

retail and consumer markets, particularly for the sale of inelastic goods.

With retailers constantly competing against one another for consumer

market share, it has become a fairly common practice for retailers to

discount certain goods, intermittently, in the hopes of increasing

foot-traffic in brick and mortar locations (websites visits for e-commerce retailers) or increasing sales of ancillary or complimentary products.

Black Friday,

a popular shopping holiday in the US, is when many retailers focus on

optimal pricing strategies to capture the holiday shopping market. In

the Black Friday scenario, retailers using game theory applications

typically ask “what is the dominant competitor’s reaction to me?"

In such a scenario, the game has two players: the retailer, and the

consumer. The retailer is focused on an optimal pricing strategy, while

the consumer is focused on the best deal. In this closed system, there

often is no dominant strategy as both players have alternative options.

That is, retailers can find a different customer, and consumers can shop

at a different retailer.

Given the market competition that day, however, the dominant strategy

for retailers lies in outperforming competitors. The open system assumes

multiple retailers selling similar goods, and a finite number of

consumers demanding the goods at an optimal price. A blog by a Cornell University professor provided an example of such a strategy, when Amazon

priced a Samsung TV $100 below retail value, effectively undercutting

competitors. Amazon made up part of the difference by increasing the

price of HDMI cables, as it has been found that consumers are less price

discriminatory when it comes to the sale of secondary items.

Retail markets continue to evolve strategies and applications of

game theory when it comes to pricing consumer goods. The key insights

found between simulations in a controlled environment and real-world

retail experiences show that the applications of such strategies are

more complex, as each retailer has to find an optimal balance between pricing, supplier relations, brand image, and the potential to cannibalize the sale of more profitable items.