Adjacent

advertisements in an 1885 newspaper for the makers of two competing ore

concentrators (machines that separate out valuable ores from undesired

minerals). The lower ad touts that their price is lower, and that their

machine's quality and efficiency was demonstrated to be higher, both of

which are general means of economic competition.

In economics, competition is a condition where different economic firms seek to obtain a share of a limited good by varying the elements of the marketing mix:

price, product, promotion and place. In classical economic thought,

competition causes commercial firms to develop new products, services

and technologies, which would give consumers greater selection and

better products. The greater selection typically causes lower prices for

the products, compared to what the price would be if there was no

competition (monopoly) or little competition (oligopoly).

Early economic research focused on the difference between price-

and non-price-based competition, while later economic theory has focused

on the many-seller limit of general equilibrium.

Role in market success

Competition is generally accepted as an essential component of markets, and results from scarcity—there

is never enough to satisfy all conceivable human wants—and occurs "when

people strive to meet the criteria that are being used to determine who

gets what." In offering goods for exchange, buyers competitively bid

to purchase specific quantities of specific goods which are available,

or might be available if sellers were to choose to offer such goods.

Similarly, sellers bid against other sellers in offering goods on the

market, competing for the attention and exchange resources of buyers.

The competitive process in a market economy exerts a sort of

pressure that tends to move resources to where they are most needed, and

to where they can be used most efficiently for the economy as a whole.

For the competitive process to work however, it is "important that

prices accurately signal costs and benefits." Where externalities occur, or monopolistic or oligopolistic conditions persist, or for the provision of certain goods such as public goods, the pressure of the competitive process is reduced.

In any given market, the power structure will either be in favor of sellers or in favor of buyers. The former case is known as a seller's market; the latter is known as a buyer's market or consumer sovereignty. In either case, the disadvantaged group is known as price-takers and the advantaged group known as price-setters.

Competition bolsters product differentiation as businesses try to

innovate and entice consumers to gain a higher market share. It helps

in improving the processes and productivity as businesses strive to

perform better than competitors with limited resources. The Australian

economy thrives on competition as it keeps the prices in check.

Historical views

In his 1776 The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith described it as the exercise of allocating productive resources to their most highly valued uses and encouraging efficiency, an explanation that quickly found support among liberal economists opposing the monopolistic practices of mercantilism, the dominant economic philosophy of the time. Smith and other classical economists before Cournot

were referring to price and non-price rivalry among producers to sell

their goods on best terms by bidding of buyers, not necessarily to a

large number of sellers nor to a market in final equilibrium.

Later microeconomic theory distinguished between perfect competition and imperfect competition, concluding that perfect competition is Pareto efficient while imperfect competition is not. Conversely, by Edgeworth's limit theorem, the addition of more firms to an imperfect market will cause the market to tend towards Pareto efficiency.

Appearance in real markets

Real

markets are never perfect. Economists who believe that in perfect

competition as a useful approximation to real markets classify markets

as ranging from close-to-perfect to very imperfect. Examples of

close-to-perfect markets typically include share and foreign exchange

markets while the real estate market is typically an example of a very

imperfect market. In such markets, the theory of the second best

proves that, even if one optimality condition in an economic model

cannot be satisfied, the next-best solution can be achieved by changing

other variables away from otherwise-optimal values.

Time variation

Within competitive markets, markets are often defined by their sub-sectors, such as the "short term" / "long term",

"seasonal" / "summer", or "broad" / "remainder" market. For example,

in otherwise competitive market economies, a large majority of the

commercial exchanges may be competitively determined by long-term

contracts and therefore long-term clearing prices. In such a scenario, a

“remainder market” is one where prices are determined by the small part

of the market that deals with the availability of goods not cleared via

long term transactions. For example, in the sugar industry,

about 94-95% of the market clearing price is determined by long-term

supply and purchase contracts. The balance of the market (and world

sugar prices) are determined by the ad hoc demand for the

remainder; quoted prices in the "remainder market" can be significantly

higher or lower than the long-term market clearing price.

Similarly, in the US real estate housing market, appraisal prices can

be determined by both short-term or long-term characteristics, depending

on short-term supply and demand factors. This can result in large

price variations for a property at one location.

Anti-competitive pressures and practices

Competition requires the existing of multiple firms, so it duplicates fixed costs.

In a small number of goods and services, the resulting cost structure

means that producing enough firms to effect competition may itself be

inefficient. These situations are known as natural monopolies and are usually publicly provided or tightly regulated.

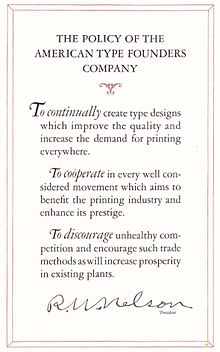

The printing equipment company American Type Founders explicitly states in its 1923 manual that its goal is to 'discourage unhealthy competition' in the printing industry.

International competition

also differentially affects sectors of national economies. In order to

protect political supporters, governments may introduce protectionist measures such as tariffs to reduce competition.

Anti-competitive practices

A practice is anti-competitive if it unfairly distorts free and effective competition in the marketplace. Examples include cartelization and evergreening.