Corporate law (also known as business law or enterprise law or sometimes company law) is the body of law governing the rights, relations, and conduct of persons, companies, organizations and businesses. The term refers to the legal practice of law relating to corporations, or to the theory of corporations. Corporate law often describes the law relating to matters which derive directly from the life-cycle of a corporation. It thus encompasses the formation, funding, governance, and death of a corporation.

While the minute nature of corporate governance as personified by share ownership, capital market, and business culture rules differ, similar legal characteristics - and legal problems - exist across many jurisdictions. Corporate law regulates how corporations, investors, shareholders, directors, employees, creditors, and other stakeholders such as consumers, the community, and the environment interact with one another. Whilst the term company or business law is colloquially used interchangeably with corporate law, business law often refers to wider concepts of commercial law, that is, the law relating to commercial or business related activities. In some cases, this may include matters relating to corporate governance or financial law. When used as a substitute for corporate law, business law means the law relating to the business corporation (or business enterprises), i.e. capital raising (through equity or debt), company formation, registration, etc.

Overview

Academics identify four legal characteristics universal to business enterprises. These are:

- Separate legal personality of the corporation (access to tort and contract law in a manner similar to a person)

- Limited liability of the shareholders (a shareholder's personal liability is limited to the value of their shares in the corporation)

- Transferable shares (if the corporation is a "public company", the shares are traded on a stock exchange)

- Delegated management under a board structure; the board of directors delegates day-to-day management of the company to executives.

Widely available and user-friendly corporate law enables business

participants to possess these four legal characteristics and thus

transact as businesses. Thus, corporate law is a response to three

endemic opportunism: conflicts between managers and shareholders,

between controlling and non-controlling shareholders; and between

shareholders and other contractual counterparts (including creditors and

employees).

A corporation

may accurately be called a company; however, a company should not

necessarily be called a corporation, which has distinct characteristics.

In the United States, a company may or may not be a separate legal

entity, and is often used synonymous with "firm" or "business."

According to Black's Law Dictionary,

in America a company means "a corporation — or, less commonly, an

association, partnership or union — that carries on industrial

enterprise." Other types of business associations can include partnerships (in the UK governed by the Partnership Act 1890), or trusts

(Such as a pension fund), or companies limited by guarantee (like some

community organizations or charities). Corporate law deals with

companies that are incorporated or registered under the corporate or

company law of a sovereign state or their sub-national states.

The defining feature of a corporation is its legal independence

from the shareholders that own it. Under corporate law, corporations of

all sizes have separate legal personality, with limited or unlimited liability for its shareholders. Shareholders control the company through a board of directors which, in turn, typically delegates control of the corporation's day-to-day operations to a full-time executive.

Shareholders' losses, in the event of liquidation, are limited to their

stake in the corporation, and they are not liable for any remaining

debts owed to the corporation's creditors. This rule is called limited liability, and it is why the names of corporations end with "Ltd.". or some variant such as "Inc." or "plc").

Under almost all legal systems

corporations have much the same legal rights and obligations as

individuals. In some jurisdictions, this extends to allow corporations

to exercise human rights against real individuals and the state, and they may be responsible for human rights violations. Just as they are "born" into existence through its members obtaining a certificate of incorporation, they can "die" when they lose money into insolvency. Corporations can even be convicted of criminal offences, such as corporate fraud and corporate manslaughter.

Corporate Law Background

In

order to understand the role corporate law plays within commercial law,

it is useful to understand the historical development of the

corporation, and the development of modern company law.

History of the Corporation

Although some forms of companies are thought to have existed during Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece,

the closest recognizable ancestors of the modern company did not appear

until the 16th century. With increasing international trade, Royal charters were granted in Europe (notably in England and Holland)

to merchant adventurers. The Royal charters usually conferred special

privileges on the trading company (including, usually, some form of monopoly).

Originally, traders in these entities traded stock on their own

account, but later the members came to operate on joint account and with

joint stock, and the new Joint stock company was born.

Early companies were purely economic ventures; it was only a

belatedly established benefit of holding joint stock that the company's

stock could not be seized for the debts of any individual member. The development of company law in Europe was hampered by two notorious "bubbles" (the South Sea Bubble in England and the Tulip Bulb Bubble in the Dutch Republic)

in the 17th century, which set the development of companies in the two

leading jurisdictions back by over a century in popular estimation.

Modern company law

"Jack and the Giant Joint-Stock", a cartoon in Town Talk (1858) satirizing the 'monster' joint-stock economy that came into being after the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844.

Companies, almost inevitably, returned to the forefront of commerce, although in England to circumvent the Bubble Act 1720 investors had reverted to trading the stock of unincorporated associations, until it was repealed in 1825.

However, the cumbersome process of obtaining Royal charters was simply

insufficient to keep up with demand. In England there was a lively

trade in the charters of defunct companies. However, procrastination

amongst the legislature meant that in the United Kingdom it was not

until the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 that the first equivalent of modern companies, formed by registration, appeared. Soon after came the Limited Liability Act 1855,

which in the event of a company's bankruptcy limited the liability of

all shareholders to the amount of capital they had invested.

The beginning of modern company law came when the two pieces of legislation were codified under the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856 at the behest of the then Vice President of the Board of Trade, Mr Robert Lowe.

That legislation shortly gave way to the railway boom, and from there

the numbers of companies formed soared. In the later nineteenth century

depression took hold, and just as company numbers had boomed, many began

to implode and fall into insolvency. Much strong academic, legislative

and judicial opinion was opposed to the notion that businessmen could

escape accountability for their role in the failing businesses. The last

significant development in the history of companies was the decision of

the House of Lords in Salomon v. Salomon & Co.

where the House of Lords confirmed the separate legal personality of

the company, and that the liabilities of the company were separate and

distinct from those of its owners.

In a December 2006 article, The Economist

identified the development of the joint stock company as one of the key

reasons why Western commerce moved ahead of its rivals in the Middle

East in post-renaissance era.

Corporate Structure

The law of business organizations originally derived from the common law of England, and has evolved significantly in the 20th century. In common law countries today, the most commonly addressed forms are:

- Corporation

- Limited company

- Unlimited company

- Limited liability partnership

- Limited partnership

- Not-for-profit corporation

- Company limited by guarantee

- Partnership

- Sole Proprietorship

The proprietary limited company is a statutory business form in several countries, including Australia.

Many countries have forms of business entity unique to that country,

although there are equivalents elsewhere. Examples are the limited liability company (LLC) and the limited liability limited partnership (LLLP) in the United States. Other types of business organizations, such as cooperatives, credit unions and publicly owned enterprises, can be established with purposes that parallel, supersede, or even replace the profit maximization mandate of business corporations.

There are various types of company that can be formed in different jurisdictions, but the most common forms of company are:

- a company limited by guarantee. Commonly used where companies are formed for non-commercial purposes, such as clubs or charities. The members guarantee the payment of certain (usually nominal) amounts if the company goes into insolvent liquidation, but otherwise they have no economic rights in relation to the company .

- a company limited by guarantee with a share capital. A hybrid entity, usually used where the company is formed for non-commercial purposes, but the activities of the company are partly funded by investors who expect a return.

- a company limited by shares. The most common form of company used for business ventures.

- an unlimited company either with or without a share capital. This is a hybrid company, a company similar to its limited company (Ltd.) counterpart but where the members or shareholders do not benefit from limited liability should the company ever go into formal liquidation.

There are, however, many specific categories of corporations and

other business organizations which may be formed in various countries

and jurisdictions throughout the world.

Corporate legal personality

One of the key legal features of corporations are their separate

legal personality, also known as "personhood" or being "artificial

persons". However, the separate legal personality was not confirmed

under English law until 1895 by the House of Lords in Salomon v. Salomon & Co. Separate legal personality often has unintended consequences, particularly in relation to smaller, family companies. In B v. B [1978] Fam 181 it was held that a discovery order

obtained by a wife against her husband was not effective against the

husband's company as it was not named in the order and was separate and

distinct from him. And in Macaura v. Northern Assurance Co Ltd

a claim under an insurance policy failed where the insured had

transferred timber from his name into the name of a company wholly owned

by him, and it was subsequently destroyed in a fire; as the property

now belonged to the company and not to him, he no longer had an

"insurable interest" in it and his claim failed.

Separate legal personality allows corporate groups flexibility in

relation to tax planning, and management of overseas liability. For

instance in Adams v. Cape Industries plc

it was held that victims of asbestos poisoning at the hands of an

American subsidiary could not sue the English parent in tort. Whilst

academic discussion highlights certain specific situations where courts

are generally prepared to "pierce the corporate veil",

to look directly at, and impose liability directly on the individuals

behind the company; the actually practice of piercing the corporate veil

is, at English law, non-existent.

However, the court will look beyond the corporate form where the

corporation is a sham or perpetuating a fraud. The most commonly cited

examples are:

- where the company is a mere façade

- where the company is effectively just the agent of its members or controllers

- where a representative of the company has taken some personal responsibility for a statement or action

- where the company is engaged in fraud or other criminal wrongdoing

- where the natural interpretation of a contract or statute is as a reference to the corporate group and not the individual company

- where permitted by statute (for example, many jurisdictions provide for shareholder liability where a company breaches environmental protection laws)

Capacity and powers

Historically, because companies are artificial persons created by

operation of law, the law prescribed what the company could and could

not do. Usually this was an expression of the commercial purpose which

the company was formed for, and came to be referred to as the company's objects, and the extent of the objects are referred to as the company's capacity. If an activity fell outside the company's capacity it was said to be ultra vires and void.

By way of distinction, the organs of the company were expressed to have various corporate powers.

If the objects were the things that the company was able to do, then

the powers were the means by which it could do them. Usually

expressions of powers were limited to methods of raising capital,

although from earlier times distinctions between objects and powers have

caused lawyers difficulty.

Most jurisdictions have now modified the position by statute, and

companies generally have capacity to do all the things that a natural

person could do, and power to do it in any way that a natural person

could do it.

However, references to corporate capacity and powers have not

quite been consigned to the dustbin of legal history. In many

jurisdictions, directors can still be liable to their shareholders if

they cause the company to engage in businesses outside its objects, even

if the transactions are still valid as between the company and the

third party. And many jurisdictions also still permit transactions to

be challenged for lack of "corporate benefit", where the relevant transaction has no prospect of being for the commercial benefit of the company or its shareholders.

As artificial persons, companies can only act through human

agents. The main agent who deals with the company's management and

business is the board of directors,

but in many jurisdictions other officers can be appointed too. The

board of directors is normally elected by the members, and the other

officers are normally appointed by the board. These agents enter into

contracts on behalf of the company with third parties.

Although the company's agents owe duties to the company (and,

indirectly, to the shareholders) to exercise those powers for a proper

purpose, generally speaking third parties' rights are not impugned if it

transpires that the officers were acting improperly. Third parties are

entitled to rely on the ostensible authority of agents held out by the company to act on its behalf. A line of common law cases reaching back to Royal British Bank v Turquand

established in common law that third parties were entitled to assume

that the internal management of the company was being conducted

properly, and the rule has now been codified into statute in most

countries.

Accordingly, companies will normally be liable for all the act

and omissions of their officers and agents. This will include almost

all torts, but the law relating to crimes committed by companies is complex, and varies significantly between countries.

Corporate governance

Corporate governance is primarily the study of the power relations among a corporation's senior executives, its board of directors and those who elect them (shareholders in the "general meeting" and employees), as well as other stakeholders, such as creditors, consumers, the environment and the community at large.

One of the main differences between different countries in the internal

form of companies is between a two-tier and a one tier board. The

United Kingdom, the United States, and most Commonwealth countries have

single unified boards of directors. In Germany, companies have two

tiers, so that shareholders (and employees) elect a "supervisory board",

and then the supervisory board chooses the "management board". There is

the option to use two tiers in France, and in the new European

Companies (Societas Europaea).

Recent literature, especially from the United States, has begun to discuss corporate governance in the terms of management science.

While post-war discourse centred on how to achieve effective "corporate

democracy" for shareholders or other stakeholders, many scholars have

shifted to discussing the law in terms of principal–agent problems.

On this view, the basic issue of corporate law is that when a

"principal" party delegates his property (usually the shareholder's

capital, but also the employee's labour) into the control of an "agent"

(i.e. the director of the company) there is the possibility that the

agent will act in his own interests, be "opportunistic", rather than

fulfill the wishes of the principal. Reducing the risks of this

opportunism, or the "agency cost", is said to be central to the goal of

corporate law.

Constitution

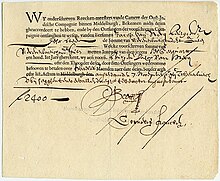

A bond issued by the Dutch East India Company, dating from 7 November 1623, for the amount of 2,400 florins

The rules for corporations derive from two sources. These are the country's statutes: in the US, usually the Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL); in the UK, the Companies Act 2006 (CA 2006); in Germany, the Aktiengesetz (AktG) and the Gesetz betreffend die Gesellschaften mit beschränkter Haftung (GmbH-Gesetz, GmbHG).

The law will set out which rules are mandatory, and which rules can be

derogated from. Examples of important rules which cannot be derogated

from would usually include how to fire the board of directors,

what duties directors owe to the company or when a company must be

dissolved as it approaches bankruptcy. Examples of rules that members of

a company would be allowed to change and choose could include, what

kind of procedure general meetings

should follow, when dividends get paid out, or how many members (beyond

a minimum set out in the law) can amend the constitution. Usually, the

statute will set out model articles, which the corporation's constitution will be assumed to have if it is silent on a bit of particular procedure.

The United States, and a few other common law countries, split

the corporate constitution into two separate documents (the UK got rid

of this in 2006). The memorandum of Association (or articles of incorporation)

is the primary document, and will generally regulate the company's

activities with the outside world. It states which objects the company

is meant to follow (e.g. "this company makes automobiles") and specifies

the authorised share capital of the company. The articles of association (or by-laws)

is the secondary document, and will generally regulate the company's

internal affairs and management, such as procedures for board meetings,

dividend entitlements etc. In the event of any inconsistency, the

memorandum prevails and in the United States only the memorandum is publicised. In civil law jurisdictions, the company's constitution is normally consolidated into a single document, often called the charter.

It is quite common for members of a company to supplement the corporate constitution with additional arrangements, such as shareholders' agreements,

whereby they agree to exercise their membership rights in a certain

way. Conceptually a shareholders' agreement fulfills many of the same

functions as the corporate constitution, but because it is a contract,

it will not normally bind new members of the company unless they accede

to it somehow.

One benefit of shareholders' agreement is that they will usually be

confidential, as most jurisdictions do not require shareholders'

agreements to be publicly filed. Another common method of supplementing

the corporate constitution is by means of voting trusts, although these are relatively uncommon outside the United States and certain offshore jurisdictions. Some jurisdictions consider the company seal

to be a part of the "constitution" (in the loose sense of the word) of

the company, but the requirement for a seal has been abrogated by

legislation in most countries.

Balance of power

Adolf Berle in The Modern Corporation and Private Property

argued that the separation of control of companies from the investors

who were meant to own them endangered the American economy and led to a

mal-distribution of wealth.

The most important rules for corporate governance are those concerning the balance of power between the board of directors

and the members of the company. Authority is given or "delegated" to

the board to manage the company for the success of the investors.

Certain specific decision rights are often reserved for shareholders,

where their interests could be fundamentally affected. There are

necessarily rules on when directors can be removed from office and

replaced. To do that, meetings need to be called to vote on the issues.

How easily the constitution can be amended and by whom necessarily

affects the relations of power.

It is a principle of corporate law that the directors of a

company have the right to manage. This is expressed in statute in the DGCL, where §141(a) states,

(a) The business and affairs of every corporation organized under this chapter shall be managed by or under the direction of a board of directors, except as may be otherwise provided in this chapter or in its certificate of incorporation.

In Germany, §76 AktG says the same for the management board, while under §111 AktG the supervisory board's role is stated to be to "oversee" (überwachen). In the United Kingdom, the right to manage is not laid down in law, but is found in Part.2 of the Model Articles. This means it is a default rule, which companies can opt out of (s.20 CA 2006)

by reserving powers to members, although companies rarely do. UK law

specifically reserves shareholders right and duty to approve

"substantial non cash asset transactions" (s.190 CA 2006), which means

those over 10% of company value, with a minimum of £5,000 and a maximum

of £100,000. Similar rules, though much less stringent, exist in §271 DGCL and through case law in Germany under the so-called Holzmüller-Doktrin.

Probably the most fundamental guarantee that directors will act

in the members' interests is that they can easily be sacked. During the Great Depression, two Harvard scholars, Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means wrote The Modern Corporation and Private Property,

an attack on American law which failed to hold directors to account,

and linked the growing power and autonomy of directors to the economic

crisis. In the UK, the right of members to remove directors by a simple

majority is assured under s.168 CA 2006

Moreover, Art.21 of the Model Articles requires a third of the board to

put themselves up for re-election every year (in effect creating

maximum three year terms). 10% of shareholders can demand a meeting any

time, and 5% can if it has been a year since the last one (s.303 CA

2006). In Germany, where employee participation creates the need for

greater boardroom stability, §84(3) AktG states that management board

directors can only be removed by the supervisory board for an important

reason (ein wichtiger Grund) though this can include a vote of

no-confidence by the shareholders. Terms last for five years, unless 75%

of shareholders vote otherwise. §122 AktG lets 10% of shareholders

demand a meeting. In the US, Delaware lets directors enjoy considerable

autonomy. §141(k) DGCL states that directors can be removed without any

cause, unless the board is "classified", meaning that directors only

come up for re-appointment on different years. If the board is

classified, then directors cannot be removed unless there is gross

misconduct. Director's autonomy from shareholders is seen further in

§216 DGCL, which allows for plurality voting and §211(d) which states

shareholder meetings can only be called if the constitution allows for

it.

The problem is that in America, directors usually choose where a

company is incorporated and §242(b)(1) DGCL says any constitutional

amendment requires a resolution by the directors. By contrast,

constitutional amendments can be made at any time by 75% of shareholders

in Germany (§179 AktG) and the UK (s.21 CA 2006).

Director duties

In most jurisdictions, directors owe strict duties of good faith,

as well as duties of care and skill, to safeguard the interests of the

company and the members. In many developed countries outside the English

speaking world, company boards are appointed as representatives of both

shareholders and employees to "codetermine" company strategy. Corporate law is often divided into corporate governance (which concerns the various power relations within a corporation) and corporate finance (which concerns the rules on how capital is used).

Directors also owe strict duties not to permit any conflict of interest

or conflict with their duty to act in the best interests of the

company. This rule is so strictly enforced that, even where the

conflict of interest or conflict of duty is purely hypothetical, the

directors can be forced to disgorge all personal gains arising from it.

In Aberdeen Ry v. Blaikie (1854) 1 Macq HL 461 Lord Cranworth stated in his judgment that,

"A corporate body can only act by agents, and it is, of course, the duty of those agents so to act as best to promote the interests of the corporation whose affairs they are conducting. Such agents have duties to discharge of a fiduciary nature towards their principal. And it is a rule of universal application that no one, having such duties to discharge, shall be allowed to enter into engagements in which he has, or can have, a personal interest conflicting or which possibly may conflict, with the interests of those whom he is bound to protect... So strictly is this principle adhered to that no question is allowed to be raised as to the fairness or unfairness of the contract entered into..."

However, in many jurisdictions the members of the

company are permitted to ratify transactions which would otherwise fall

foul of this principle.

It is also largely accepted in most jurisdictions that this principle

should be capable of being abrogated in the company's constitution.

The standard of skill and care that a director owes is usually

described as acquiring and maintaining sufficient knowledge and

understanding of the company's business to enable him to properly

discharge his duties. This duty enables the company to seek compensation

from its director if it can be proved that a director has not shown

reasonable skill or care which in turn has caused the company to incur a

loss. In many jurisdictions, where a company continues to trade despite foreseeable bankruptcy,

the directors can be forced to account for trading losses personally.

Directors are also strictly charged to exercise their powers only for a

proper purpose. For instance, were a director to issue a large number

of new shares, not for the purposes of raising capital but in order to

defeat a potential takeover bid, that would be an improper purpose.

Company law theory

Ronald Coase

has pointed out, all business organizations represent an attempt to

avoid certain costs associated with doing business. Each is meant to

facilitate the contribution of specific resources - investment capital,

knowledge, relationships, and so forth - towards a venture which will

prove profitable to all contributors. Except for the partnership, all

business forms are designed to provide limited liability to both members of the organization and external investors. Business organizations originated with agency law,

which permits an agent to act on behalf of a principal, in exchange for

the principal assuming equal liability for the wrongful acts committed

by the agent. For this reason, all partners in a typical general

partnership may be held liable for the wrongs committed by one partner.

Those forms that provide limited liability are able to do so because the

state provides a mechanism by which businesses that follow certain

guidelines will be able to escape the full liability imposed under

agency law. The state provides these forms because it has an interest in

the strength of the companies that provide jobs and services therein,

but also has an interest in monitoring and regulating their behaviour.

Litigation

Members of a company generally have rights against each other and

against the company, as framed under the company's constitution.

However, members cannot generally claim against third parties who cause

damage to the company which results in a diminution in the value of

their shares or others membership interests because this is treated as "reflective loss" and the law normally regards the company as the proper claimant in such cases.

In relation to the exercise of their rights, minority

shareholders usually have to accept that, because of the limits of their

voting rights, they cannot direct the overall control of the company

and must accept the will of the majority (often expressed as majority rule).

However, majority rule can be iniquitous, particularly where there is

one controlling shareholder. Accordingly, a number of exceptions have

developed in law in relation to the general principle of majority rule.

- Where the majority shareholder(s) are exercising their votes to perpetrate a fraud on the minority, the courts may permit the minority to sue

- members always retain the right to sue if the majority acts to invade their personal rights, e.g. where the company's affairs are not conducted in accordance with the company's constitution (this position has been debated because the extent of a personal right is not set in law). Macdougall v Gardiner and Pender v Lushington present irreconcilable differences in this area.

- in many jurisdictions it is possible for minority shareholders to take a representative or derivative action in the name of the company, where the company is controlled by the alleged wrongdoers

Corporate finance

Through the operational life of the corporation, perhaps the most

crucial aspect of corporate law relates to raising capital for the

business to operate. The law, as it relates to corporate finance, not

only provides the framework for which a business raises funds - but also

provides a forum for principles and policies which drive the

fundraising, to be taken seriously. Two primary methods of financing

exists with regard to corporate financing, these are:

- Equity financing; and

- Debt financing

Each has relative advantages and disadvantages, both at law and

economically. Additional methods of raising capital necessary to finance

its operations is that of retained profits Various combinations of financing structures

have the capacity to produce fine-tuned transactions which, using the

advantages of each form of financing, support the limitations of the

corporate form, its industry, or economic sector.

A mix of both debt and equity is crucial to the sustained health of the

company, and its overall market value is independent of its capital

structure. One notable difference is that interest payments to debt is

tax deductible whilst payment of dividends are not, this will

incentivise a company to issue debt financing rather than preferred stock in order to reduce their tax exposure.

A company limited by shares, whether public or private, must have at least one issued share; however, depending on the corporate structure,

the formatting may differ. If a company wishes to raise capital through

equity, it will usually be done by issuing shares. (sometimes called

"stock" (not to be confused with stock-in-trade)) or warrants.

In the common law, whilst a shareholder is often colloquially referred

to as the owner of the company - it is clear that the shareholder is not

an owner of the company but makes the shareholder a member of the

company and entitles them to enforce the provisions of the company's

constitution against the company and against other members.

A share is an item of property, and can be sold or transferred. Shares

also normally have a nominal or par value, which is the limit of the

shareholder's liability to contribute to the debts of the company on an

insolvent liquidation. Shares usually confer a number of rights on the

holder. These will normally include:

- voting rights

- rights to dividends (or payments made by companies to their shareholders) declared by the company

- rights to any return of capital either upon redemption of the share, or upon the liquidation of the company

- in some countries, shareholders have preemption rights, whereby they have a preferential right to participate in future share issues by the company

Companies may issue different types of shares, called "classes" of

shares, offering different rights to the shareholders depending on the

underlying regulatory rules pertaining to corporate structures,

taxation, and capital market rules. A company might issue both ordinary

shares and preference shares, with the two types having different voting

and/or economic rights. It might provide that preference shareholders

shall each receive a cumulative preferred dividend of a certain amount

per annum, but the ordinary shareholders shall receive everything else.

Corporations will structure capital raising in this way in order to

appeal to different lenders in the market by providing different

incentives for investment. The total value of issued shares in a company is said to represent its equity capital. Most jurisdictions regulate the minimum amount of capital which a company may have, although some jurisdictions prescribe minimum amounts of capital for companies engaging in certain types of business (e.g. banking, insurance etc.).

Similarly, most jurisdictions regulate the maintenance of equity

capital, and prevent companies returning funds to shareholders by way of

distribution when this might leave the company financially exposed.

Often this extends to prohibiting a company from providing financial assistance for the purchase of its own shares.

Dissolution

Events such as mergers, acquisitions, insolvency, or the commission of a crime affect the corporate form.

In addition to the creation of the corporation, and its financing,

these events serve as a transition phase into either dissolution, or

some other material shift.

Mergers and acquisitions

A merger or acquisition can often mean the altering or extinguishing of the corporation.

Corporate insolvency

If unable to discharge its debts in a timely manner, a corporation

may end up on bankruptcy liquidation. Liquidation is the normal means by

which a company's existence is brought to an end. It is also referred

to (either alternatively or concurrently) in some jurisdictions as winding up or dissolution. Liquidations generally come in two forms — either compulsory liquidations (sometimes called creditors' liquidations) and voluntary liquidations (sometimes called members' liquidations,

although a voluntary liquidation where the company is insolvent will

also be controlled by the creditors, and is properly referred to as a creditors' voluntary liquidation). Where a company goes into liquidation, normally a liquidator

is appointed to gather in all the company's assets and settle all

claims against the company. If there is any surplus after paying off all

the creditors of the company, this surplus is then distributed to the

members.

As its names imply, applications for compulsory liquidation are normally made by creditors

of the company when the company is unable to pay its debts. However,

in some jurisdictions, regulators have the power to apply for the

liquidation of the company on the grounds of public good, i.e., where

the company is believed to have engaged in unlawful conduct, or conduct

which is otherwise harmful to the public at large.

Voluntary liquidations occur when the company's members decide

voluntarily to wind up the affairs of the company. This may be because

they believe that the company will soon become insolvent,

or it may be on economic grounds if they believe that the purpose for

which the company was formed is now at an end, or that the company is

not providing an adequate return on assets and should be broken up and

sold off.

Some jurisdictions also permit companies to be wound up on "just and equitable" grounds.

Generally, applications for just and equitable winding-up are brought

by a member of the company who alleges that the affairs of the company

are being conducted in a prejudicial manner, and asking the court to

bring an end to the company's existence. For obvious reasons, in most

countries, the courts have been reluctant to wind up a company solely on

the basis of the disappointment of one member, regardless of how

well-founded that member's complaints are. Accordingly, most

jurisdictions that permit just and equitable winding up also permit the

court to impose other remedies, such as requiring the majority

shareholder(s) to buy out the disappointed minority shareholder at a

fair value.

Insider dealing

Insider trading is the trading of a corporation's stock or other securities (e.g., bonds or stock options)

by individuals with potential access to non-public information about

the company. In most countries, trading by corporate insiders such as

officers, key employees, directors, and large shareholders may be legal

if this trading is done in a way that does not take advantage of

non-public information. However, the term is frequently used to refer to

a practice in which an insider or a related party trades based on material non-public information obtained during the performance of the insider's duties at the corporation, or otherwise in breach of a fiduciary or other relationship of trust and confidence or where the non-public information was misappropriated from the company.

Illegal insider trading is believed to raise the cost of capital for

securities issuers, thus decreasing overall economic growth.

In the United States and several other jurisdictions, trading

conducted by corporate officers, key employees, directors, or

significant shareholders (in the United States, defined as beneficial

owners of ten percent or more of the firm's equity securities) must be

reported to the regulator or publicly disclosed, usually within a few

business days of the trade. Many investors follow the summaries of these

insider trades in the hope that mimicking these trades will be

profitable. While "legal" insider trading cannot be based on material non-public information,

some investors believe corporate insiders nonetheless may have better

insights into the health of a corporation (broadly speaking) and that

their trades otherwise convey important information (e.g., about the

pending retirement of an important officer selling shares, greater

commitment to the corporation by officers purchasing shares, etc.)

Trends and developments

Most case law on the matter of corporate governance dates to the 1980s and primarily addresses hostile takeovers, however, current research considers the direction of legal reforms to address issues of shareholder activism, institutional investors and capital market intermediaries.

Corporations and boards are challenged to respond to these

developments. Shareholder demographics have been effected by trends in

worker retirement, with more institutional intermediaries like mutual funds

playing a role in employee retirement. These funds are more motivated

to partner with employers to have their fund included in a company's

retirement plans than to vote their shares – corporate governance

activities only increase costs for the fund, while the benefits would be

shared equally with competitor funds.

Shareholder activism prioritizes wealth maximization and has been

criticized as a poor basis for determining corporate governance rules.

Shareholders do not decide corporate policy, that is done by the board

of directors, but shareholders may vote to elect board directors and on

mergers and other changes that have been approved by directors. They may

also vote to amend corporate bylaws. Broadly speaking there have been three movements in 20th century American law that sought a federal corporate law: the Progressive Movement, some aspects of proposals made in the early stages of the New Deal

and again in the 1970s during a debate about the effect of corporate

decision making on states. However, these movements did not establish

federal incorporation. Although there has been some federal involvement

in corporate governance rules as a result, the relative rights of

shareholders and corporate officers is still mostly regulated by state

laws. There is no federal legislation like there is for corporate

political contributions or regulation of monopolies and federal laws

have developed along different lines than state laws.

United States

In the United States, most corporations are incorporated, or organized, under the laws of a particular state.

The laws of the state of incorporation normally governs a corporation's

internal operations, even if the corporation's operations take place

outside that state. Corporate law differs from state to state. Because of these differences, some businesses will benefit from having a corporate lawyer determine the most appropriate or advantageous state in which to incorporate.

Business entities may also be regulated by federal laws and in some cases by local laws and ordinances.

Delaware

A majority of publicly traded companies in the U.S. are Delaware corporations. Some companies choose to incorporate in Delaware because the Delaware General Corporation Law offers lower corporate taxes than many other states. Many venture capitalists prefer to invest in Delaware corporations. Also, the Delaware Court of Chancery is widely recognized as a good venue for the litigation of business disputes.