In microeconomics, diseconomies of scale are the cost disadvantages that economic actors accrue due to an increase in organizational size or in output, resulting in production of goods and services at increased per-unit costs. The concept of diseconomies of scale is the opposite of economies of scale. In business, diseconomies of scale are the features that lead to an increase in average costs as a business grows beyond a certain size.

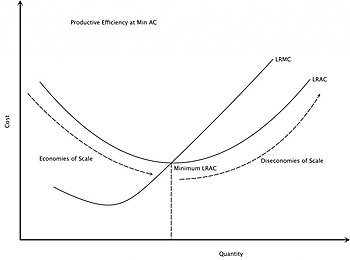

The rising part of the long-run average cost

curve illustrates the effect of diseconomies of scale. The Long Run

Average Cost (LRAC) curve plots the average cost of producing the lowest

cost method. The Long Run Marginal Cost (LRMC) is the change in total

cost attributable to a change in the output of one unit after the plant

size has been adjusted to produce that rate of output at minimum LRAC.

Causes

Communication costs

Ideally,

all employees of a firm would have one-on-one communication with each

other so they know exactly what the other workers are doing. A firm with

a single worker does not require any communication between employees. A

firm with two workers requires one communication channel, directly

between those two workers. A firm with three workers requires three

communication channels between employees (between employees A & B, B

& C, and A & C). Here is a chart of one-on-one communication

channels required:

| Workers | Communication Channels |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 6 |

| 5 | 10 |

| n |

The graph of all one-on-one channels is a complete graph.

The number of one-on-one channels of communication grows more

rapidly than the number of workers, thus increasing the time and costs

of communication. At some point one-on-one communications between all

workers becomes impractical; therefore only certain groups of employees

will communicate with one another (e.g. within departments or within

geographical locations). This reduces, but does not stop, the increase

in unit costs; and also the organisation will incur some inefficiencies

due to the reduced level of communication.

Duplication of effort

An organisation with just one person cannot have any duplication of effort

between employees. If there are two employees, there could be some

duplication of efforts, but this is likely to be minor, as each of the

two will generally know what the other is working on. When organisations

grow to thousands of workers, it is inevitable that someone, or even a

team, will take on a function that is already being handled by another

person or team. In colloquial terms, this is described as "one hand not

knowing what the other hand is doing". General Motors, for example, developed two in-house CAD/CAM

systems: CADANCE was designed by the GM Design Staff, while Fisher

Graphics was created by the former Fisher Body division. These similar

systems later needed to be combined into a single Corporate Graphics

System, CGS, at great expense. A smaller firm would have had neither the

money to allow such expensive parallel developments, nor the lack of

communication and cooperation which precipitated this event. In addition

to CGS, GM also used CADAM, UNIGRAPHICS, CATIA

and other off-the-shelf CAD/CAM systems, thus increasing the cost of

translating designs from one system to another. This endeavor eventually

became so unmanageable that they acquired (and then eventually sold

off) Electronic Data Systems

(EDS) in an effort to control the situation. Smaller firms typically

choose a single off-the-shelf CAD/CAM system, with no need to combine or

translate between systems.

Office politics

"Office politics"

is management behavior which a manager knows is counter to the best

interest of the company, but is in his personal best interest. For

example, a manager might intentionally promote an incompetent worker,

knowing that the worker will never be able to compete for the manager's

job. This type of behavior only makes sense in a company with multiple

levels of management. The more levels there are, the more opportunity

for this behavior. In a small company, such behavior could cause the

company to go bankrupt, and thus cost the manager his job, so he would

not make such a decision. In a large company, one manager would not have

much effect on the overall health of the company, so such "office

politics" are in the interest of individual managers.

Top-heavy companies

As

an organisation increases in size, it becomes costly to keep control of

a sprawling corporate empire, and this often results in bureaucracy as

executives implement more and more levels of management. As firms

increase in size, managers will initially provide a net benefit to the

firm and increase productivity; however, as a firm grows and covers a

larger geographical area and/or employs more people, a principal–agent problem

arises, leading to lower productivity. To counter this, executives

introduce standards and controls in order to maintain productivity, and

this necessitates the hiring of more managers to apply these standards

and controls, hence the proportion of managerial to working class begins

to lean towards managerial and the company becomes "top-heavy".

However, these additional managers are not providing additional output:

they are spending their time implementing standards and carrying out

supervision that is unnecessary in smaller firms, hence the

cost-per-unit has increased.

Supply-chain disruption

Global emergencies, such as COVID-19

in 2020, can easily disrupt supply chains. This disruption has a higher

chance of affecting large organizations - especially when there is only

a few large suppliers. Smaller organizations with robust, local supply

networks can manage supply chain shocks because any localized shock has a

smaller effect on the overall ecosystem.

Other effects which reduce competitiveness of large firms

These do not always increase the cost-per-unit, but do reduce the ability of a large firm to compete.

Cannibalization

A

small firm only competes with other firms, but larger firms frequently

find their own products are competing with each other. A Buick was just as likely to steal customers from another GM make, such as an Oldsmobile,

as it was to steal customers from other companies. This may help to

explain why Oldsmobiles were discontinued after 2004. This self-competition wastes resources that should be used to compete with other firms.

Isolation of decision-makers from the results of their decisions

If

a single person makes and sells donuts and decides to try jalapeño

flavoring, they would likely know on the same day whether their decision

was good or not, based on the reaction of customers. A decision-maker

at a huge company that makes donuts may not know for many months if such

a decision is embraced by consumers or if it is rejected, especially if

their research or marketing team fails to respond in a timely manner.

By that time, the decision-makers may very well have moved on to another

division or company and thus see no consequence from their decision.

This lack of consequences can lead to poor decisions and cause an

upward-sloping average cost curve.

Slow response time

In

a reverse example, the smaller firm will know immediately if people

begin to request other products, and be able to respond the next day. A

large company would need to do research, create an assembly line,

determine which distribution chains to use, plan an advertising

campaign, etc., before any changes could be made. By this time, the

smaller competitors may well have grabbed that market niche.

Inertia (Unwillingness to change)

This will be defined as the "we've always done it that way, so there's no need to ever change" attitude (see appeal to tradition).

An old, successful company is far more likely to have this attitude

than a new, struggling one. While "change for change's sake" is

counter-productive, refusal to consider change, even when indicated, is

likewise toxic to a company, as changes in the industry and market

conditions will inevitably demand changes in the firm in order to remain

successful. An example is Polaroid Corporation's delay in moving into digital imaging, which adversely affected the company, ultimately leading to bankruptcy.

Public and government opposition

Such opposition is largely a function of the size of the firm. Behavior from Microsoft, which would have been ignored from a smaller firm, was seen as an anti-competitive and monopolistic threat, due to Microsoft's size, thus bringing about government lawsuits.

A

small company with only a 1% market share could relatively easily

double market share, and hence revenues, in a year. A large company with

50% market share will find it difficult to do so.

Large market portfolio

A

small investment fund can potentially yield a higher return because it

can concentrate its investments in a small number of good opportunities

without driving up the purchase price as they buy in, and later sell

them without driving down the sale price as they sell off. Conversely, a

large investment fund must spread its investments among so many

securities that its results tend to track those of the market as a

whole. As the size of the market controlled grows, the results will be

closer to market average.

Inelasticity of supply

A

company which is heavily dependent on a resource supply of a fixed or

relatively-fixed size will have trouble increasing production. For

instance, a timber company cannot increase production above the

sustainable harvest rate of its land (although it can still increase

production by acquiring more land). Similarly, service companies are

limited by available labor (and thus tend to concentrate in large,

densely-populated metropolitan areas); STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) professions are often-cited examples.

Reputation

Larger

firms have a reputation to uphold and as a result may place more

restrictions on employees, limiting their efficiency. This will be seen

amplified in a regulated industry, where a company losing its license

would be an extremely serious event.

Large

firms also tend to be old and in mature markets. Both of these have

negative implications for future growth. Old firms tend to have a large

retiree base, with high associated pension and health costs, and also

tend to be unionized, with associated higher labor costs and lower productivity.

Mature markets tend to only offer the potential for small, incremental

growth. (Everybody might go out and buy a new invention next year, but

it is unlikely they will all buy cars next year, since most people

already have them.)

Impact on smaller firms

While

diseconomies of scale are typically associated with large mature firms,

similar problems have been observed in the growth phase of small and

medium-sized manufacturing companies. Mclean

has observed that this can occur once the workforce exceeds around 20

employees. At this point business complexity grows more rapidly than

revenue. The business experiences falling productivity, leading to

rising variable costs along with rapidly rising overheads.

Solutions

Solutions

to the diseconomies of scale for large firms may involve splitting the

company into smaller organisations. This can either happen by default

when the company is in financial difficulties, sells off its profitable

divisions and shuts down the rest; or can happen proactively, if the

management is willing.

To avoid the negative effects of diseconomies of scale, a firm

must stick to the lowest average output cost and try to recognise any

external diseconomies of scale. Moreover, on reaching the lowest average

cost, a firm must either expand to other countries to increase demand

for its products, or seek new markets or produce new products that do

not compete with its original products. However, neither of these

actions will necessarily eliminate communications and management

problems often associated with large organisations.

A systematic analysis and redesign of business processes,

in order to reduce complexity, can counter diseconomies of scale. (Of

course, this phase of analysis and revamping in itself can be, and

usually is, a diseconomy leading to hiring of new personnel and

investment in new, competing systems.) This leads to increased

productivity. Improved management systems and more effective control of

labor and operations can lower overhead.

Example

Returning

to the example of the large donut firm, each retail location could be

allowed to operate relatively autonomously from the company

headquarters.

For instance, the local management may decide on the following factors instead of relying on the central management:

- Employee decisions such as hiring, firing, promotions and wage scales, where the local management is directly involved and likely to have better understanding of each employee. For instance, employers may choose to offer higher wages and charge higher prices if they are in an affluent area.

- Purchasing decisions, with each location allowed to choose its own suppliers, which may or may not be owned by the corporation (wherever they find the best quality and prices).

- Research and marketing decisions. Each firm may decide to develop their own recipes or utilise different signature flavour unique to their locale. For instance, when fresh apple cider is available at bargain prices from local farmers in October, they may choose to market a cinnamon donut and hot apple cider combo.

While a single, large, centrally-controlled firm may have higher

ability to innovate and develop or market new products more effectively

than when its resources are divided, it may lack the flexibility to

offer individual customizations. Allowing the different retail locations

to make decisions independent of the central management may allow them

to meet local consumers' demands more efficiently.

In addition, if the employees own a portion of the local

business, employees will also have a more vested interest in its

success.

Note that all these changes will likely result in a substantial

reduction in corporate headquarters staff and other support staff. For

this reason, many businesses delay such a reorganization until it is too

late to be effective. However, the whole company incurs reputation and

legal risks arising from each unit.