Example of associations between graphemes and colors that are described more accurately as ideasthesia than as synesthesia

Ideasthesia (alternative spelling ideaesthesia) was

introduced by neuroscientist Danko Nikolić and is defined as a

phenomenon in which activations of concepts (inducers) evoke

perception-like experiences (concurrents). The name comes from the Ancient Greek ἰδέα (idéa) and αἴσθησις (aísthēsis), meaning "sensing concepts" or "sensing ideas". The main reason for introducing the notion of ideasthesia was the problems with synesthesia. While "synesthesia" means "union of senses", empirical evidence indicated that this was an incorrect explanation of a set of phenomena traditionally covered by this heading. Syn-aesthesis

denoting also "co-perceiving", implies the association of two sensory

elements with little connection to the cognitive level. However,

according to others, most phenomena that have inadvertently been linked to synesthesia in fact are induced by the semantic representations. That is, the meaning

of the stimulus is what is important rather than its sensory

properties, as would be implied by the term synesthesia. In other words,

while synesthesia presumes that both the trigger (inducer) and the

resulting experience (concurrent) are of sensory nature, ideasthesia

presumes that only the resulting experience is of sensory nature while

the trigger is semantic. Meanwhile, the concept of ideasthesia developed

into a theory of how we perceive and the research has extended to

topics other than synesthesia — as the concept of ideasthesia turned out

applicable to our everyday perception.

Ideasthesia has been even applied to the theory of art. Research on

ideasthesia bears important implications for solving the mystery of

human conscious experience, which, according to ideasthesia, is grounded in how we activate concepts.

Examples and evidence

A drawing by a synesthete which illustrates time unit-space synesthesia/ideasthesia.

The months in a year are organized into a circle surrounding the

synesthete's body, each month having a fixed location in space and a

unique color.

A common example of synesthesia is the association between graphemes and colors, usually referred to as grapheme-color synesthesia.

Here, letters of the alphabet are associated with vivid experiences of

color. Studies have indicated that the perceived color is

context-dependent and is determined by the extracted meaning of a

stimulus. For example, an ambiguous stimulus '5' that can be interpreted

either as 'S' or '5' will have the color associated with 'S' or with

'5', depending on the context in which it is presented. If presented

among numbers, it will be interpreted as '5' and will associate the

respective color. If presented among letters, it will be interpreted as

'S' and will associate the respective synesthetic color.

Evidence for grapheme-color synesthesia comes also from the

finding that colors can be flexibly associated to graphemes, as new

meanings become assigned to those graphemes. In one study synesthetes

were presented with Glagolitic

letters that they have never seen before, and the meaning was acquired

through a short writing exercise. The Glagolitic graphemes inherited the

colors of the corresponding Latin graphemes as soon as the Glagolitic

graphemes acquired the new meaning.

In another study, synesthetes were prompted to form novel

synesthetic associations to graphemes never seen before. Synesthetes

created those associations within minutes or seconds - which was time

too short to account for creation of new physical connections between

color representation and grapheme representation areas in the brain,

pointing again towards ideasthesia. Although the time course is

consistent with postsynaptic AMPA receptor upregulation and/or NMDA

receptor coactivation, which would imply that the realtime experience is

invoked at the synaptic level of analysis prior to establishment of

novel wiring per se, a very intuitively appealing model.

For lexical-gustatory synesthesia

evidence also points towards ideasthesia: In lexical-gustatory

synesthesia, verbalisation of the stimulus is not necessary for the

experience of concurrents. Instead, it is sufficient to activate the

concept.

Another case of synesthesia is swimming-style synesthesia in

which each swimming style is associated with a vivid experience of a

color.

These synesthetes do not need to perform the actual movements of a

corresponding swimming style. To activate the concurrent experiences, it

is sufficient to activate the concept of a swimming style (e.g., by

presenting a photograph of a swimmer or simply talking about swimming).

It has been argued that grapheme-color synesthesia for geminate consonants also provides evidence for ideasthesia.

In pitch-color synesthesia, the same tone will be associated with

different colors depending on how it has been named; do-sharp (i.e. di)

will have colors similar to do (e.g., a reddish color) and re-flat

(i.e. ra) will have color similar to that of re (e.g., yellowish),

although the two classes refer to the same tone. Similar semantic associations have been found between the acoustic characteristics of vowels and the notion of size.

One-shot synesthesia: There are synesthetic experiences

that can occur just once in a lifetime, and are thus dubbed one-shot

synesthesia. Investigation of such cases has indicated that such unique

experiences typically occur when a synesthete is involved in an

intensive mental and emotional activity such as making important plans

for one's future or reflecting on one's life. It has been thus concluded

that this is also a form of ideasthesia.

In normal perception

Which

one would be called Bouba and which Kiki? Responses are highly

consistent among people. This is an example of ideasthesia as the

conceptualization of the stimulus plays an important role.

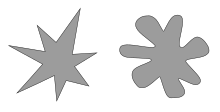

Recently, it has been suggested that the Bouba/Kiki phenomenon is a case of ideasthesia. Most people will agree that the star-shaped object on the left is named Kiki and the round one on the right Bouba. It has been assumed that these associations come from direct connections between visual and auditory cortices.

For example, according to that hypothesis, representations of sharp

inflections in the star-shaped object would be physically connected to

the representations of sharp inflection in the sound of Kiki. However,

Gomez et al.

have shown that Kiki/Bouba associations are much richer as either word

and either image is associated semantically to a number of concepts such

as white or black color, feminine vs. masculine, cold vs. hot, and

others. These sound-shape associations seem to be related through a

large overlap between semantic networks

of Kiki and star-shape on one hand, and Bouba and round-shape on the

other hand. For example, both Kiki and star-shape are clever, small,

thin and nervous. This indicates that behind Kiki-Bouba effect lies a

rich semantic network. In other words, our sensory experience is largely

determined by the meaning that we assign to stimuli. Food description

and wine tasting is another domain in which ideasthetic association

between flavor and other modalities such as shape may play an important

role.

These semantic-like relations play a role in successful marketing; the

name of a product should match its other characteristics.

Implications for development of synesthesia

The concept of ideasthesia bears implications for understanding how synesthesia develops

in children. Synesthetic children may associate concrete sensory-like

experiences primarily to the abstract concepts that they have otherwise

difficulties dealing with.

Synesthesia may thus be used as a cognitive tool to cope with the

abstractness of the learning materials imposed by the educational system

— referred to also as a "semantic vacuum hypothesis". This hypothesis

explains why the most common inducers in synesthesia are graphemes and

time units — both relating to the first truly abstract ideas that a

child needs to master.

Implications for art theory

The concept of ideasthesia has been often discussed in relation to art, and also used to formulate a psychological theory of art.

According to the theory, we consider something to be a piece of art

when experiences induced by the piece are accurately balanced with

semantics induced by the same piece. Thus, a piece of art makes us both

strongly think and strongly experience. Moreover, the two must be

perfectly balanced such that the most salient stimulus or event is both

the one that evokes strongest experiences (fear, joy, ... ) and

strongest cognition (recall, memory, ...) — in other words, idea is well balanced with aesthesia.

Ideasthesia theory of art may be used for psychological studies of aesthetics. It may also help explain classificatory disputes about art

as its main tenet is that experience of art can only be individual,

depending on person's unique knowledge, experiences and history. There could exist no general classification of art satisfactorily applicable to each and all individuals.

Neurophysiology of ideasthesia

Ideasthesia is congruent with the theory of brain functioning known as practopoiesis.

According to that theory, concepts are not an emergent property of

highly developed, specialized neuronal networks in the brain, as is

usually assumed; rather, concepts are proposed to be fundamental to the

very adaptive principles by which living systems and the brain operate.