The genetic history of Africa is composed of the overall genetic history of African populations, including the regional genetic histories of North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa, as well as the recent African origin of modern humans. The Sahara served as a trans-regional passageway and place of dwelling for people in Africa during various humid phases and periods throughout the history of Africa.

Overview

The people of Africa, the largest and culturally most diverse continent, are characterized by regional genetic substructure, and heterogeneity depending on the respective ethno-linguistic identity, which can be in part explained by the "multiregional evolution" of modern human lineages in various multiple regions of the African continent, as well as later admixture events, and back-migrations from Eurasia, including both highly differentiated West-Eurasian and East-Eurasian components.

Africans genetic ancestry is largely partitioned by geography and language family, with populations belonging to the same, or related, ethno-linguistic groupings showing high genetic homogeneity and coherence, however mixed ancestry in several individuals, consistent with both short- and long-range migration events followed by extensive admixture and bottleneck events, have influenced the genetic makeup and demographic structure of Africans. The historical Bantu expansion had lasting impacts on the modern demographic make up of Africa, resulting in a greater genetic and linguistic homogenization. Genetic, archeologic, and linguistic studies added extra insight into this movement: "Our results reveal a genetic continuum of Niger–Congo speaker populations across the continent and extend our current understanding of the routes, timing and extent of the Bantu migration."

Overall, different African populations display genetic diversity and substructure, but can be clustered in two distinct but partially overlapping groupings: The first and largest grouping consists of Niger-Congo-speakers and Nilo-Saharan-speakers from West Africa, Central Africa, and East Africa, which are occasionally designated as "Sub-Saharan Africans" in population genomics. The Khoisan, hunter-gatherers from Southern Africa, form an divergent branch, suggesting early isolation from other African groups. The second grouping consists of mostly, but not exclusively, Afroasiatic-speakers and Austronesian-speakers from Northern Africa and parts of the Horn of Africa, as well as from Madagascar respectively, which have received significant Eurasian admixture in varying degrees. The Niger-Congo-speakers, together with Nilo-Saharans, form a tight cluster, while the Khoisan, Afroasiatic and Austronesian groups are more diverged from other Africans, either through more diverged ancestry or from Eurasian admixture. Overall, African populations are closer to each other than to outside populations, except certain groups from coastal North Africa, which are relatively more close to Europeans and Middle Easterners.

Indigenous Africans

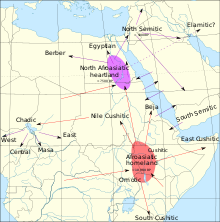

The indigenous population of Africa consists of Niger–Congo speakers, Nilo-Saharan speakers, the diverse Khoisan grouping, as well as several unclassified or isolated ethnolinguistic groupings (see unclassified languages of Africa). The origin of the Afroasiatic languages remains disputed, with some proposing an Middle Eastern origin, while others support an indigenous African origin.

The Niger–Congo languages probably originated in or near the area where these languages were spoken prior to Bantu expansion (i.e. West Africa or Central Africa). Its expansion may have been associated with the expansion of agriculture, during in the African Neolithic period, following the desiccation of the Sahara in c. 3500 BCE. Proto-Niger-Congo may have originated about 10,000 years before present in the "Green Sahara" of Africa (roughly the Sahel and southern Sahara), and that its dispersal can be correlated with the spread of the bow and arrow by migrating hunter-gatherers, which later developed agriculture.

Although the validity of the Nilo-Saharan family remains controversial, the region between Chad, Sudan, and the Central African Republic is seen as a likely candidate for its homeland prior to its dispersal around 10,000–8,000 BCE.

The Southern African hunter-gatherers (Khoisan) are suggested to represent the early diverged indigenous population of parts of Southern Africa, prior to the Bantu expansion, and were genetically isolated from surrounding populations until ~2,000 years ago, with many Khoisan samples showing high amounts of Bantu-related admixture, ranging from ~0% to up to ~87.1% of their ancestry, but also minor Eurasian-like admixture.

Out-of-Africa event

The model proposes a "single origin" of Homo sapiens in Africa the taxonomic sense. Recent genetic and archeologic data suggests that Homo sapiens-subgroups originated in multiple regions of Africa, not confined to a single region of origin. The H. sapiens ancestral to proper Eurasians most likely developed in various regions of Northeastern Africa, between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. The "recent African origin" model proposes that all modern non-African populations are substantially descended from one or several diverse waves of H. sapiens that left Africa, through the Arabian Peninsula, at about 110,000 years ago, with some proposing an earlier date.

According to a 2020 study by Durvasula et al., there are indications that 2% to 19% (≃6.6%) of the DNA of West African populations may have come from an unknown archaic hominin which split from the ancestor of humans and Neanderthals between 360 kya to 1.02 mya. However, the study also suggests that at least part of this archaic admixture is also present in Eurasians/non-Africans, and that the admixture event or events range from 0 to 124 ka B.P, which includes the period before the Out-of-Africa migration and prior to the African/Eurasian split (thus affecting in part the common ancestors of both Africans and Eurasians/non-Africans). Another academic paper from 2020 (Chen et al.) found that Africans have higher Neanderthal ancestry than previously thought. 2,504 African samples from all over Africa were analyzed and tested on Neanderthal ancestry. All African samples showed evidence for minor Neanderthal ancestry, but always at lower levels than observed in Eurasians.

Geneflow between Eurasia and African populations

Eurasian ancestry is found in many parts of Africa in varying degrees, but generally at low frequency. Eurasian admixture peaks amongst populations of Northern Africa, and among some ethnic groups of the Horn of Africa, as well as among the Malagasy people of Madagascar. A genome study (Busby et al. 2016) shows evidence for prehistoric back-migrations from Eurasian populations and following admixture with native groups.

Another study (Ramsay et al. 2018) also found evidence for Eurasian admixture in parts Africa, from both ancient and more recent migrations, being highest among populations from Northern Africa, parts of the Horn of Africa and parts of the Sahel zone:

This distinctive Eurasian admixture appears to have occurred over at least three time periods with ancient admixture in central west Africa (e.g. Yoruba from Nigeria) occurring between ~7.5 and 10.5 kya, older admixture in east Africa (e.g. Ethiopia) occurring between ~2.4 and 3.2 kya and more recent admixture between ~0.15 and 1.5 kya in some east African (e.g. Kenyan) populations.Subsequent studies based on LD decay and haplotype sharing in an extensive set of African and Eurasian populations confirmed the presence of Eurasian signatures in west, east and southern Africans. In the west, in addition to Niger-Congo speakers from The Gambia and Mali, the Mossi from Burkina Faso showed the oldest Eurasian admixture event ~7 kya. In the east, these analyses inferred Eurasian admixture within the last 4000 years in Kenya.

A previous 2014 genome study by Hodgson et al. indicated the (West-) Eurasian admixture in the Northern Africa and the Horn of Africa was already from about 23,000 years ago. There is evidence that some Western Eurasian admixture arrived in Northeast Africa (particularly the Horn of Africa) in the Neolithic, with some moving south eventually reaching southern Africa.

Afroasiatic languages are suggested to have been spreaded by people with largely West Eurasian ancestry during the Neolithic Revolution, towards Northern Africa and the Horn of Africa, outgoing from the Middle East, specifically from the Levant. While there is no definitive agreement on when or where the original homeland of the Afroasiatic language family existed, many link the first speakers to the earliest farmers in the Levant, who would later spread to North and Northeastern Africa, spreading West-Eurasian ancestry and merging with local indigenous Africans. A 2015 study by Dobon et al. identified an ancestral autosomal component that is commonly found among many modern Afroasiatic-speaking populations in Northern Africa. This component formed from a majority of West-Eurasian ancestry and minor African ancestry. The authors proposed that Afroasiatic spread with this component and may be traced back to an Ancestral West-Eurasian source population. However some others argue that the first speakers of Afroasiatic (Proto-Afroasiatic) were of indigenous African origin, and based in North East Africa, probably near the Red sea. They argue that Proto-Afroasiatic migrated during the late Paleolithic into the Levant, merging with local West-Eurasians, resulting in a population which would later give rise to Natufian culture, which is frequently associated with early Afroasiatic-speaking communities, or specifically with early Semitic languages. This Natufian-related population would later spread Afroasiatic languages, resulting in their modern distribution and genetic makeup. A 2018 analysis of autosomal DNA using modern populations as a reference, found that the ancient Natufian samples were largely of local West-Eurasian origin, but harbored 6.8% Omotic-related ancestry (related to modern Sub-Saharan Africans). It is suggested that this Omotic/African component may be associated with the spread of Proto-Afroasiatic and the specific Y-haplogroup sublineage E-M215, also known as "E1b1b", to Western Eurasia. Further evidence for this are the results published in a 2017 paper about previous genetic data of Northern African populations, such as Berbers. Northern African populations have been described as a mosaic of Middle Eastern, European, and Sub-Saharan African-related ancestries.

Specific East Asian-related ancestry is found among the Malagasy speakers of Madagascar at low to medium frequency. The presence of this East Asian-related ancestry is mostly linked to the Austronesian peoples expansion from Southeast Asia. The peoples of Borneo were identified to resemble the East Asian voyagers, who arrived on Madagascar.

A 2020 study by Chen et al. analyzed 2,504 African samples from all over Africa, and found archaic Neanderthal ancestry, among all tested African samples at low frequency. They also identified an European-related (West-Eurasian) ancestry segment, which seems to largely correspond with the detected Neanderthal ancestry components. Eurasian admixture among Africans was estimated to be between ~0% to up to 30%.

According to the authors:

These data are consistent with the hypothesis that back-migration contributed to the signal of Neanderthal ancestry in Africans. Furthermore, the data indicates that this back-migration came after the split of Europeans and East Asians, from a population related to the European lineage."

A 2021 paper by Hollfelder et al., concluded that West African Yoruba people, which were previously used as "unadmixed reference population" for indigenous Africans, harbor minor levels of Neanderthal ancestry, which can be largely associated with back-migration of an "Ancestral European-like" source population.

Multiple studies found also evidence for minor geneflow of indigenous African ancestry towards Eurasia, specifically Europe and the Middle East. The analysis of 40 different West-Eurasian populations found African admixture at a frequency of 1% to up to 15%. Modern Northern Africans (Egyptians) were found to carry significant indigenous African ancestry at ~25% on average, with a high variability depending on subgroups and region.

Regional genomic overview

North Africa

Archaic Human DNA

While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.

Ancient DNA

Egypt

Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamen carried the paternal haplogroup R1b. Thuya, Tiye, Tutankhamen's mother, and Tutankhamen carried the maternal haplogroup K.

Ramesses III and "Unknown Man E", possibly Pentawere, carried paternal haplogroup E1b1a.

Khnum-aa, Khnum-Nakht, and Nakht-Ankh carried maternal haplogroup M1a1.

Libya

At Takarkori rockshelter, in Libya, two naturally mummified women, dated to the Middle Pastoral Period (7000 BP), carried basal maternal haplogroup N.

Morocco

The Taforalts of Morocco, who have been radiocarbon dated between 15,100 cal BP and 13,900 cal BP, and were found to be 63.5% Natufian, were also found to be 36.5% Sub-Saharan African (e.g., Hadza), which is drawn out, most of all, by West Africans (e.g., Yoruba, Mende). In addition to having similarity with the remnant of a more basal Sub-Saharan African lineage (e.g., a basal West African lineage shared between Yoruba and Mende peoples), the Sub-Saharan African DNA in the Taforalt people of the Iberomaurusian culture may be best represented by modern West Africans (e.g., Yoruba).

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial haplogroups L3, M, and N are found among Sudanese peoples (e.g., Beja, Nilotics, Nuba, Nubians), who have no known interaction (e.g., history of migration/admixture) with Europeans or Asians; rather than having developed in a post-Out-of-Africa migration context, mitochondrial macrohaplogroup L3/M/N and its subsequent development into distinct mitochondrial haplogroups (e.g., Haplogroup L3, Haplogroup M, Haplogroup N) may have occurred in East Africa at a time that considerably predates the Out-of-Africa migration event of 50,000 BP.

Autosomal DNA

Medical DNA

Lactase Persistence

Neolithic agriculturalists, who may have resided in Northeast Africa and the Near East, may have been the source population for lactase persistence variants, including –13910*T, and may have been subsequently supplanted by later migrations of peoples. The Sub-Saharan West African Fulani, the North African Tuareg, and European agriculturalists, who are descendants of these Neolithic agriculturalists, share the lactase persistence variant –13910*T. While shared by Fulani and Tuareg herders, compared to the Tuareg variant, the Fulani variant of –13910*T has undergone a longer period of haplotype differentiation. The Fulani lactase persistence variant –13910*T may have spread, along with cattle pastoralism, between 9686 BP and 7534 BP, possibly around 8500 BP; corroborating this timeframe for the Fulani, by at least 7500 BP, there is evidence of herders engaging in the act of milking in the Central Sahara.

West Africa

Archaic Human DNA

Archaic traits found in human fossils of West Africa (e.g., Iho Eleru fossils, which dates to 13,000 BP) and Central Africa (e.g., Ishango fossils, which dates between 25,000 BP and 20,000 BP) may have developed as a result of admixture between archaic humans and modern humans or may be evidence of late-persisting early modern humans. While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.

Ancient DNA

As of 2017, human ancient DNA has not been found in the region of Western Africa. As of 2020, human ancient DNA has not been forthcoming in the region of Western Africa.

In 4000 BP, there may have been a population that traversed from Africa (e.g., West Africa or West-Central Africa), through the Strait of Gibraltar, into the Iberian peninsula, where admixing between Africans and Iberians (e.g., of northern Portugal, of southern Spain) occurred.

In Granada, a Muslim (Moor) of the Cordoba Caliphate, who was of haplogroups E1b1a1 and H1+16189, as well as estimated to date between 900 CE and 1000 CE, and a Morisco, who was of haplogroup L2e1, as well as estimated to date between 1500 CE and 1600 CE, were both found to be of Sub-Saharan West African (i.e., Gambian) and Iberian descent.

Y-Chromosomal DNA

As a result of haplogroup D0, a basal branch of haplogroup DE, being found in three Nigerian men, it may be the case that haplogroup DE, as well as its sublineages D and E, originated in Africa.

As of 19,000 years ago, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west. E1b1a1-M2 likely originated in West Africa or Central Africa.

Mitochondrial DNA

Around 18,000 BP, Mende people, along with Gambian peoples, grew in population size.

In 15,000 BP, Niger-Congo speakers may have migrated from the Sahelian region of West Africa, along the Senegal River, and introduced L2a1 into North Africa, resulting in modern Mauritanian peoples and Berbers of Tunisia inheriting it.

Between 11,000 BP and 10,000 BP, Yoruba people and Esan people grew in population size.

Up to 11,000 years ago, Sub-Saharan West Africans, bearing macrohaplogroup L (e.g., L1b1a11, L1b1a6a, L1b1a8, L1b1a9a1, L2a1k, L3d1b1a), may have migrated through North Africa and into Europe, mostly into southern Europe (e.g., Iberia).

Autosomal DNA

Between 2000 BP and 1500 BP, Nilo-Saharan-speakers may have migrated across the Sahel, from East Africa into West Africa, and admixed with Niger-Congo-speaking Berom people.

Medical DNA

Sickle Cell

Amid the Green Sahara, the mutation for sickle cell originated in the Sahara or in the northwest forest region of western Central Africa (e.g., Cameroon) by at least 7,300 years ago, though possibly as early as 22,000 years ago. The ancestral sickle cell haplotype to modern haplotypes (e.g., Cameroon/Central African Republic and Benin/Senegal haplotypes) may have first arose in the ancestors of modern West Africans, bearing haplogroups E1b1a1-L485 and E1b1a1-U175 or their ancestral haplogroup E1b1a1-M4732. West Africans (e.g., Yoruba and Esan of Nigeria), bearing the Benin sickle cell haplotype, may have migrated through the northeastern region of Africa into the western region of Arabia. West Africans (e.g., Mende of Sierra Leone), bearing the Senegal sickle cell haplotype, may have migrated into Mauritania (77% modern rate of occurrence) and Senegal (100%); they may also have migrated across the Sahara, into North Africa, and from North Africa, into Southern Europe, Turkey, and a region near northern Iraq and southern Turkey. Some may have migrated into and introduced the Senegal and Benin sickle cell haplotypes into Basra, Iraq, where both occur equally. West Africans, bearing the Benin sickle cell haplotype, may have migrated into the northern region of Iraq (69.5%), Jordan (80%), Lebanon (73%), Oman (52.1%), and Egypt (80.8%).

Schistosomes

According to Steverding (2020), while not definite: Near the African Great Lakes, schistosomes (e.g., S. mansoni, S. haematobium) underwent evolution. Subsequently, there was an expansion alongside the Nile. From Egypt, the presence of schistosomes may have expanded, via migratory Yoruba people, into Western Africa. Thereafter, schistosomes may have expanded, via migratory Bantu peoples, into the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Southern Africa, Central Africa).

Thalassemia

Through pathways taken by caravans, or via travel amid the Almovarid period, a population (e.g., Sub-Saharan West Africans) may have introduced the –29 (A → G) β-thalassemia mutation (found in notable amounts among African-Americans) into the North African region of Morocco.

Central Africa

Archaic Human DNA

Archaic traits found in human fossils of West Africa (e.g., Iho Eleru fossils, which dates to 13,000 BP) and Central Africa (e.g., Ishango fossils, which dates between 25,000 BP and 20,000 BP) may have developed as a result of admixture between archaic humans and modern humans or may be evidence of late-persisting early modern humans. While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.

Ancient DNA

In 4000 BP, there may have been a population that traversed from Africa (e.g., West Africa or West-Central Africa), through the Strait of Gibraltar, into the Iberian peninsula, where admixing between Africans and Iberians (e.g., of northern Portugal, of southern Spain) occurred.

Cameroon

West African hunter-gatherers, in the region of western Central Africa (e.g., Shum Laka, Cameroon), particularly between 8000 BP and 3000 BP, were found to be related to modern Central African hunter-gatherers (e.g., Baka, Bakola, Biaka, Bedzan).

Democratic Republic of Congo

At Kindoki, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there were three individuals, dated to the protohistoric period (230 BP, 150 BP, 230 BP); one carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1d1a2 (E-CTS99, E-CTS99) and L1c3a1b, another carried haplogroup E (E-M96, E-PF1620), and the last carried haplogroups R1b1 (R-P25 1, R-M415) and L0a1b1a1.

At Ngongo Mbata, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an individual, dated to the protohistoric period (220 BP), carried haplogroup L1c3a.

At Matangai Turu Northwest, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an individual, dated to the Iron Age (750 BP), carried an undetermined haplogroup(s).

Y-Chromosomal DNA

Haplogroup R-V88 may have originated in western Central Africa (e.g., Equatorial Guinea), and, in the middle of the Holocene, arrived in North Africa through population migration.

Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial haplogroup L1c is strongly associated with pygmies, especially with Bambenga groups. L1c prevalence was variously reported as: 100% in Ba-Kola, 97% in Aka (Ba-Benzélé), and 77% in Biaka, 100% of the Bedzan (Tikar), 97% and 100% in the Baka people of Gabon and Cameroon, respectively, 97% in Bakoya (97%), and 82% in Ba-Bongo. Mitochondrial haplogroups L2a and L0a are prevalent among the Bambuti.

Autosomal DNA

Genetically, African pygmies have some key difference between them and Bantu peoples.

Medical DNA

Evidence suggests that, when compared to other Sub-Saharan African populations, African pygmy populations display unusually low levels of expression of the genes encoding for human growth hormone and its receptor associated with low serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and short stature.

Eastern Africa

Archaic Human DNA

While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.

Ancient DNA

Ethiopia

At Mota, in Ethiopia, an individual, estimated to date to the 5th millennium BP, carried haplogroups E1b1 and L3x2a. The individual of Mota is genetically related to groups residing near the region of Mota, and in particular, are considerably genetically related to the Ari people.

Kenya

At Jawuoyo Rockshelter, in Kisumu County, Kenya, a forager of the Later Stone Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1b2/E-V22 and L4b2a2c.

At Ol Kalou, in Nyandarua County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3d1d.

At Kokurmatakore, in Marsabit County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1/E-M35 and L3a2a.

At White Rock Point, in Homa Bay County, Kenya, there were two foragers of the Later Stone Age; one carried haplogroups BT (xCT), likely B, and L2a4, and another probably carried haplogroup L0a2.

At Nyarindi Rockshelter, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Later Stone Age (3500 BP); one carried haplogroup L4b2a and another carried haplogroup E (E-M96, E-P162).

At Lukenya Hill, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (3500 BP); one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-CTS10880) and L4b2a2b, and another carried haplogroup L0f1.

At Hyrax Hill, in Kenya, an individual, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (2300 BP), carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-M293) and L5a1b.

At Molo Cave, in Kenya, there were two individuals, dated to the Pastoral Neolithic (1500 BP); while one had haplogroups that went undetermined, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-M293) and L3h1a2a1.

At Kakapel, in Kenya, there were three individuals, one dated to the Later Stone Age (3900 BP) and two dated to the Later Iron Age (300 BP, 900 BP); one carried haplogroups CT (CT-M168, CT-M5695) and L3i1, another carried haplogroup L2a1f, and the last carried haplogroup L2a5.

At Panga ya Saidi, in Kenya, an individual, estimated to date between 496 BP and 322 BP, carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2 and L4b2a2.

Laikipia County

At Kisima Farm/Porcupine Cave, in Laikipia County, Kenya, there were two pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and M1a1, and another carried haplogroup M1a1f.

At Kisima Farm/C4, in Laikipia County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age, carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and L3h1a1.

At Laikipia District Burial, in Laikipia County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroup L0a1c1.

Nakuru County

At Prettejohn's Gully, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were two pastoralists of the early pastoral period; one carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and K1a, and another carried haplogroup L3f1b.

At Cole's Burial, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1a1b1/E-CTS3282 and L3i2.

At Rigo Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were three pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan, one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3f, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293, and probably M1a1b, and the last carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L4b2a2c.

At Naishi Rockshelter, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there two pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b/E-V1515, likely E-M293, and L3x1a, and another carried haplogroups A1b (xA1b1b2a)/A-P108 and L0a2d.

At Keringet Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroups A1b1b2/A-L427 and L4b2a1, and another pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan carried haplogroup K1a.

At Naivasha Burial Site, in Nakuru County, Kenya, there were five pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroup L4b2a2b, another carried haplogroups xBT, likely A, and M1a1b, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3h1a1, another carried haplogroups A1b1b2b/A-M13 and L4a1, and the last carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3x1a.

At Njoro River Cave II, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic carried haplogroup L3h1a2a1.

At Egerton Cave, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Neolithic/Elmenteitan carried haplogroup L0a1d.

At Ilkek Mounds, in Nakuru County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E2 (xE2b)/E-M75 and L0f2a.

At Deloraine Farm, in Nakuru County, Kenya, an iron metallurgist of the Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1a1a/E-M58 and L5b1.

Narok County

At Kasiole 2, in Narok County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b/E-V1515, likely E-M293, and L3h1a2a1.

At Emurua Ole Polos, in Narok County, Kenya, a pastoralist of the Pastoral Iron Age carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3h1a2a1.

Tanzania

At Luxmanda, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 3141 BP and 2890 BP, carried haplogroup L2a1.

At Kuumbi Cave, in Zanzibar, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 1370 BP and 1303 BP, carried haplogroup L4b2a2c.

Karatu District

At Gishimangeda Cave, in Karatu District, Tanzania, there were eleven pastoralists of the Pastoral Neolithic; one carried haplogroups E1b1b1a1b2/E-V22 and HV1b1, another carried haplogroup L0a, another carried haplogroup L3x1, another carried haplogroup L4b2a2b, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2a1/E-M293 and L3i2, another carried haplogroup L3h1a2a1, another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293 and L0f2a1, and another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b2/E-V1486, likely E-M293, and T2+150; while most of the haplogroups among three pastoralists went undetermined, one was determined to carry haplogroup BT, likely B.

Pemba Island

At Makangale Cave, on Pemba Island, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 1421 BP and 1307 BP, carried haplogroup L0a.

At Makangale Cave, on Pemba Island, Tanzania, an individual, estimated to date between 639 BP and 544 BP, carried haplogroup L2a1a2.

Uganda

At Munsa, in Uganda, an individual, dated to the Later Iron Age (500 BP), carried haplogroup L3b1a1.

Y-Chromosomal DNA

As of 19,000 years ago, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west.

Before the slave trade period, East Africans, who carried haplogroup E1b1a-M2, expanded into Arabia, resulting in various rates of inheritance throughout Arabia (e.g., 2.8% Qatar, 3.2% Yemen, 5.5% United Arab Emirates, 7.4% Oman).

Mitochondrial DNA

Autosomal DNA

Across all areas of Madagascar, the average ancestry for the Malagasy people was found to be 4% West Eurasian, 37% Austronesian, and 59% Bantu.

Medical DNA

Southern Africa

Archaic Human DNA

While Denisovan and Neanderthal ancestry in non-Africans outside of Africa are more certain, archaic human ancestry in Africans is less certain and is too early to be established with certainty.

Ancient DNA

Three Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers carried ancient DNA similar to Khoisan-speaking hunter-gatherers. Prior to the Bantu migration into the region, as evidenced by ancient DNA from Botswana, East African herders migrated into Southern Africa. Out of four Iron Age Bantu agriculturalists of West African origin, two earlier agriculturalists carried ancient DNA similar to Tsonga and Venda peoples and the two later agriculturalists carried ancient DNA similar to Nguni people; this indicates that there were various movements of peoples in the overall Bantu migration, which resulted in increased interaction and admixing between Bantu-speaking peoples and Khoisan-speaking peoples.

Botswana

At Nqoma, in Botswana, an individual, dated to the Early Iron Age (900 BP), carried haplogroup L2a1f.

At Taukome, in Botswana, an individual, dated to the Early Iron Age (1100 BP), carried haplogroups E1b1a1 (E-M2, E-Z1123) and L0d3b1.

At Xaro, in Botswana, there were two individuals, dated to the Early Iron Age (1400 BP); one carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1c1a and L3e1a2, and another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-CTS10880) and L0k1a2.

Malawi

Fingira

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 6175 BP and 5913 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0d1b2b.

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 6177 BP and 5923 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0d1c.

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 2676 BP and 2330 BP, carried haplogroup L0f.

Chencherere

At Chencherere, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 5400 BP and 4800 BP, carried haplogroup L0k2.

At Chencherere, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 5293 BP and 4979 BP, carried haplogroup L0k1.

Hora

At Hora, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 10,000 BP and 5000 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0k2.

At Hora, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 8173 BP and 7957 BP, carried haplogroup L0a2.

South Africa

At Doonside, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2296 BP and 1910 BP, carried haplogroup L0d2.

At Champagne Castle, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 448 BP and 282 BP, carried haplogroup L0d2a1a.

At Eland Cave, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 533 BP and 453 BP, carried haplogroup L3e3b1.

At Mfongosi, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 448 BP and 308 BP, carried haplogroup L3e1b2.

At Newcastle, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 508 BP and 327 BP, carried haplogroup L3e2b1a2.

At St. Helena, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2241 BP and 1965 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2a and L0d2c1.

At Faraoskop Rock Shelter, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2017 BP and 1748 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2a and L0d1b2b1b.

At Kasteelberg, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 1282 BP and 1069 BP, carried haplogroup L0d1a1a.

At Vaalkrans Shelter, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date to 200 BP, is predominantly related to Khoisan speakers, partly related (15% - 32%) to East Africans, and carried haplogroups L0d3b1.

Ballito Bay

At Ballito Bay, South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 1986 BP and 1831 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2 and L0d2c1.

At Ballito Bay, South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2149 BP and 1932 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2 and L0d2a1.

Y-Chromosomal DNA

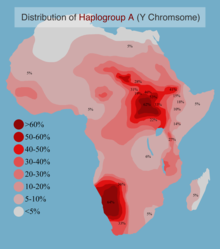

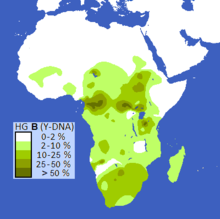

Various Y chromosome studies show that the San carry some of the most divergent (oldest) human Y-chromosome haplogroups. These haplogroups are specific sub-groups of haplogroups A and B, the two earliest branches on the human Y-chromosome tree.

Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA studies also provide evidence that the San carry high frequencies of the earliest haplogroup branches in the human mitochondrial DNA tree. This DNA is inherited only from one's mother. The most divergent (oldest) mitochondrial haplogroup, L0d, has been identified at its highest frequencies in the southern African San groups.

Autosomal DNA

In a study published in March 2011, Brenna Henn and colleagues found that the ǂKhomani San, as well as the Sandawe and Hadza peoples of Tanzania, were the most genetically diverse of any living humans studied. This high degree of genetic diversity hints at the origin of anatomically modern humans.

Medical DNA

Among the ancient DNA from three hunter-gatherers sharing genetic similarity with San people and four Iron Age agriculturalists, their SNPs indicated that they bore variants for resistance against sleeping sickness and Plasmodium vivax. In particular, two out of the four Iron Age agriculturalists bore variants for resistance against sleeping sickness and three out of the four Iron Age agriculturalists bore Duffy negative variants for resistance against malaria. In contrast to the Iron Age agriculturalists, from among the San-related hunter-gatherers, a six-year-old boy may have died from schistosomiasis. In Botswana, a man, who dates to 1400 BP, may have also carried the Duffy negative variant for resistance against malaria.

Recent African origin of modern humans

Between 500,000 BP and 300,000 BP, anatomically modern humans may have emerged in Africa. As Africans (e.g., Y-Chromosomal Adam, Mitochondrial Eve) have migrated from their places of origin in Africa to other locations in Africa, and as the time of divergence for East African, Central African, and West African lineages are similar to the time of divergence for the Southern African lineage, there is insufficient evidence to identify a specific region for the origin of humans in Africa. In 100,000 BP, anatomically modern humans migrated from Africa into Eurasia. Subsequently, tens of thousands of years after, the ancestors of all present-day Eurasians migrated from Africa into Eurasia and eventually became admixed with Denisovans and Neanderthals.