An interstellar object is an astronomical object (such as an asteroid, a comet, or a rogue planet, but not a star) in interstellar space that is not gravitationally bound to a star. This term can also be applied to an object that is on an interstellar trajectory but is temporarily passing close to a star, such as certain asteroids and comets (including exocomets). In the latter case, the object may be called an interstellar interloper.

The first interstellar objects discovered were rogue planets, planets ejected from their original stellar system (e.g., OTS 44 or Cha 110913−773444), though they are difficult to distinguish from sub-brown dwarfs, planet-mass objects that formed in interstellar space as stars do.

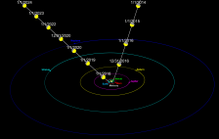

The first interstellar object which was discovered traveling through the Solar System was 1I/ʻOumuamua in 2017. The second was 2I/Borisov in 2019. They both possess significant hyperbolic excess velocity, indicating they did not originate in the Solar System. The discovery of ʻOumuamua inspired the identification of CNEOS 2014-01-08, also known as the Manus Island fireball, as an interstellar object that impacted the Earth. This was confirmed by the U.S. Space Command in 2022 based on the object's velocity relative to the Sun. In May 2023, astronomers reported the possible capture of other interstellar objects in Near Earth Orbit (NEO) over the years.

Nomenclature

With the first discovery of an interstellar object in the Solar System, the IAU has proposed a new series of small-body designations for interstellar objects, the I numbers, similar to the comet numbering system. The Minor Planet Center will assign the numbers. Provisional designations for interstellar objects will be handled using the C/ or A/ prefix (comet or asteroid), as appropriate.

Overview

| Object | Velocity |

|---|---|

| C/2012 S1 (ISON) (weakly hyperbolic Oort Cloud comet) |

0.2 km/s 0.04 au/yr |

| Voyager 1 (For comparison) |

16.9 km/s 3.57 au/yr |

| 1I/2017 U1 (ʻOumuamua) | 26.33 km/s 5.55 au/yr |

| 2I/Borisov | 32.1 km/s 6.77 au/yr |

| 2014Jan08 bolide (in peer review) |

43.8 km/s 9.24 au/yr |

Astronomers estimate that several interstellar objects of extrasolar origin (like ʻOumuamua) pass inside the orbit of Earth each year, and that 10,000 are passing inside the orbit of Neptune on any given day.

Interstellar comets occasionally pass through the inner Solar System and approach with random velocities, mostly from the direction of the constellation Hercules because the Solar System is moving in that direction, called the solar apex. Until the discovery of 'Oumuamua, the fact that no comet with a speed greater than the Sun's escape velocity had been observed was used to place upper limits to their density in interstellar space. A paper by Torbett indicated that the density was no more than 1013 (10 trillion) comets per cubic parsec. Other analyses, of data from LINEAR, set the upper limit at 4.5×10−4/AU3, or 1012 (1 trillion) comets per cubic parsec. A more recent estimate by David C. Jewitt and colleagues, following the detection of 'Oumuamua, predicts that "The steady-state population of similar, ~100 m scale interstellar objects inside the orbit of Neptune is ~1×104, each with a residence time of ~10 years."

Current models of Oort cloud formation predict that more comets are ejected into interstellar space than are retained in the Oort cloud, with estimates varying from 3 to 100 times as many. Other simulations suggest that 90–99% of comets are ejected. There is no reason to believe comets formed in other star systems would not be similarly scattered. Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb demonstrated that the Oort Cloud could have been formed from ejected planetesimals from other stars in the Sun's birth cluster.

It is possible for objects orbiting a star to be ejected due to interaction with a third massive body, thereby becoming interstellar objects. Such a process was initiated in the early 1980s when C/1980 E1, initially gravitationally bound to the Sun, passed near Jupiter and was accelerated sufficiently to reach escape velocity from the Solar System. This changed its orbit from elliptical to hyperbolic and made it the most eccentric known object at the time, with an eccentricity of 1.057. It is heading for interstellar space.

Due to present observational difficulties, an interstellar object can usually only be detected if it passes through the Solar System, where it can be distinguished by its strongly hyperbolic trajectory and hyperbolic excess velocity of more than a few km/s, proving that it is not gravitationally bound to the Sun. In contrast, gravitationally bound objects follow elliptic orbits around the Sun. (There are a few objects whose orbits are so close to parabolic that their gravitationally bound status is unclear.)

An interstellar comet can probably, on rare occasions, be captured into a heliocentric orbit while passing through the Solar System. Computer simulations show that Jupiter is the only planet massive enough to capture one, and that this can be expected to occur once every sixty million years. Comets Machholz 1 and Hyakutake C/1996 B2 are possible examples of such comets. They have atypical chemical makeups for comets in the Solar System.

Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb proposed a search for ʻOumuamua-like objects which are trapped in the Solar System as a result of losing orbital energy through a close encounter with Jupiter. They identified centaur candidates, such as 2017 SV13 and 2018 TL6, as captured interstellar objects that could be visited by dedicated missions. The authors pointed out that future sky surveys, such as Vera C. Rubin Observatory, should find many candidates.

Recent research suggests that asteroid 514107 Kaʻepaokaʻawela may be a former interstellar object, captured some 4.5 billion years ago, as evidenced by its co-orbital motion with Jupiter and its retrograde orbit around the Sun. In addition, comet C/2018 V1 (Machholz-Fujikawa-Iwamoto) has a significant probability (72.6%) of having an extrasolar provenance although an origin in the Oort cloud cannot be excluded. Harvard astronomers suggest that matter—and potentially dormant spores—can be exchanged across vast distances. The detection of ʻOumuamua crossing the inner Solar System confirms the possibility of a material link with exoplanetary systems.

Interstellar visitors in the Solar System cover the whole range of sizes – from kilometer large objects down to submicron particles. Also, interstellar dust and meteoroids carry with them valuable information from their parent systems. Detection of these objects along the continuum of sizes is, however, not evident (see Figure). The smallest interstellar dust particles are filtered out of the solar system by electromagnetic forces, while the largest ones are too sparse to obtain good statistics from in situ spacecraft detectors. Discrimination between interstellar and interplanetary populations can be a challenge for intermediate (0.1–1 micrometer) sizes. These can vary widely in velocity and directionality. The identification of interstellar meteoroids, observed in the Earth's atmosphere as meteors, is highly challenging and requires high accuracy measurements and appropriate error examinations. Otherwise, measurement errors can transfer near-parabolic orbits over the parabolic limit and create an artificial population of hyperbolic particles, often interpreted as of interstellar origin. Large interstellar visitors like asteroids and comets were detected the first time in the solar system in 2017 (1I/'Oumuamua) and 2019 (2I/Borisov) and are expected to be detected more frequently with new telescopes, e.g. the Vera Rubin Observatory. Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb have predicted that the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will be capable of detecting an anisotropy in the distribution of interstellar objects due to the Sun's motion relative to the Local Standard of Rest and identify the characteristic ejection speed of interstellar objects from their parent stars.

In May 2023, astronomers reported the possible capture of other interstellar objects in Near Earth Orbit (NEO) over the years.

In July 2023, Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb reported the possibility of finding interstellar material.

Confirmed objects

1I/2017 U1 (ʻOumuamua)

A dim object was discovered on October 19, 2017, by the Pan-STARRS telescope, at an apparent magnitude of 20. The observations showed that it follows a strongly hyperbolic trajectory around the Sun at a speed greater than the solar escape velocity, in turn meaning that it is not gravitationally bound to the Solar System and likely to be an interstellar object. It was initially named C/2017 U1 because it was assumed to be a comet, and was renamed to A/2017 U1 after no cometary activity was found on October 25. After its interstellar nature was confirmed, it was renamed to 1I/ʻOumuamua – "1" because it is the first such object to be discovered, "I" for interstellar, and "‘Oumuamua" is a Hawaiian word meaning "a messenger from afar arriving first".

The lack of cometary activity from ʻOumuamua suggests an origin from the inner regions of whatever stellar system it came from, losing all surface volatiles within the frost line, much like the rocky asteroids, extinct comets and damocloids we know from the Solar System. This is only a suggestion, as ʻOumuamua might very well have lost all surface volatiles to eons of cosmic radiation exposure in interstellar space, developing a thick crust layer after it was expelled from its parent system.

ʻOumuamua has an eccentricity of 1.199, which was the highest eccentricity ever observed for any object in the Solar System by a wide margin prior to the discovery of comet 2I/Borisov in August 2019.

In September 2018, astronomers described several possible home star systems from which ʻOumuamua may have begun its interstellar journey.

2I/Borisov

The object was discovered on 30 August 2019 at MARGO, Nauchnyy, Crimea by Gennadiy Borisov using his custom-built 0.65-meter telescope. On 13 September 2019, the Gran Telescopio Canarias obtained a low-resolution visible spectrum of 2I/Borisov that revealed that this object has a surface composition not too different from that found in typical Oort Cloud comets. The IAU Working Group for Small Body Nomenclature kept the name Borisov, giving the comet the interstellar designation of 2I/Borisov. On 12 March 2020, astronomers reported observational evidence of "ongoing nucleus fragmentation" from Borisov.

Candidates

In 2007, Afanasiev et al. reported the likely detection of a multi-centimeter intergalactic meteor hitting the atmosphere above the Special Astrophysical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences on July 28, 2006.

In November 2018, Harvard astronomers Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb reported that there should be hundreds of 'Oumuamua-size interstellar objects in the Solar System, based on calculated orbital characteristics, and presented several centaur candidates such as 2017 SV13 and 2018 TL6. These are all orbiting the Sun, but may have been captured in the distant past.

Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb have proposed methods for increasing the discovery rate of interstellar objects that include stellar occultations, optical signatures from impacts with the moon or the Earth's atmosphere, and radio flares from collisions with neutron stars.

2014 interstellar meteor

CNEOS 2014-01-08 (also known as Interstellar meteor 1; IM1), a meteor with a mass of 0.46 tons and width of 0.45 m (1.5 ft), burned up in the Earth's atmosphere on January 8, 2014. A 2019 preprint suggested this meteor had been of interstellar origin. It had a heliocentric speed of 60 km/s (37 mi/s) and an asymptotic speed of 42.1 ± 5.5 km/s (26.2 ± 3.4 mi/s), and it exploded at 17:05:34 UTC near Papua New Guinea at an altitude of 18.7 km (61,000 ft). After declassifying the data in April 2022, the U.S. Space Command, based on information collected from its planetary defense sensors, confirmed the velocity of the potential interstellar meteor. In 2023, The Galileo Project completed an expedition to retrieve small fragments of the apparently peculiar meteor. Claims about their findings have been doubted by their peers according to a report in The New York Times. Further related studies were reported on 1 September 2023.

Other astronomers doubt the interstellar origin because the meteoroid catalog used does not report uncertainties on the incoming velocity. The validity of any single data point (especially for smaller meteoroids) remains questionable. In November 2022, a paper was published, claiming the anomalous properties (including its high strength and strongly hyperbolic trajectory) of CNEOS 2014-01-08 are better described as measurement error rather than genuine parameters. Successful retrieval of any meteoroid fragments is highly unlikely. Common micrometeorites would be indistinguishable from one another.

2017 interstellar meteor

CNEOS 2017-03-09 (aka Interstellar meteor 2; IM2), a meteor with a mass of roughly 6.3 tons, burned up in the Earth's atmosphere on March 9, 2017. Similar to IM1, it has a high mechanical strength.

In September 2022, astronomers Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb reported the discovery of a candidate interstellar meteor, CNEOS 2017-03-09 (aka Interstellar meteor 2; IM2), that impacted Earth in 2017 and is considered, based in part on the high material strength of the meteor, to be a possible interstellar object.

Hypothetical missions

With current space technology, close visits and orbital missions are challenging due to their high speeds, though not impossible.

The Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is) launched in 2017 Project Lyra to assess the feasibility of a mission to ʻOumuamua. Several options for sending a spacecraft to ʻOumuamua within a time-frame of 5 to 25 years were suggested. One option is using first a Jupiter flyby followed by a close solar flyby at 3 solar radii (2.1×106 km; 1.3×106 mi) in order to take advantage of the Oberth effect. Different mission durations and their velocity requirements were explored with respect to the launch date, assuming direct impulsive transfer to the intercept trajectory.

The Comet Interceptor spacecraft by ESA and JAXA, planned to launch in 2029, will be positioned at the Sun-Earth L2 point to wait for a suitable long-period comet to intercept and flyby for study. In case that no suitable comet is identified during its 3-year wait, the spacecraft could be tasked to intercept an interstellar object in short notice, if reachable.