American civil religion is a sociological theory that a nonsectarian quasi-religious faith exists within the United States

with sacred symbols drawn from national history. Scholars have

portrayed it as a cohesive force, a common set of values that foster

social and cultural integration. The ritualistic elements of ceremonial deism

found in American ceremonies and presidential invocations of God can be

seen as expressions of the American civil religion. The very heavy

emphasis on pan-Christian religious themes is quite distinctively

American and the theory is designed to explain this.

The concept goes back to the 19th century, but in current form, the theory was developed by sociologist Robert Bellah in 1967 in his article, "Civil Religion in America". The topic soon became the major focus at religious sociology conferences and numerous articles and books were written on the subject. The debate reached its peak with the American Bicentennial celebration in 1976. There is a viewpoint that some Americans have come to see the document of the United States Constitution, along with the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights as cornerstones of a type of civic or civil religion or political religion. Political sociologist Anthony Squiers argues that these texts act as the sacred writ of the American civil religion because they are used as authoritative symbols in what he calls the politics of the sacred. The politics of the sacred, according to Squiers are "the attempt to define and dictate what is in accord with the civil religious sacred and what is not. It is a battle to define what can and cannot be and what should and should not be tolerated and accepted in the community, based on its relation to that which is sacred for that community."

According to Bellah, Americans embrace a common "civil religion" with certain fundamental beliefs, values, holidays, and rituals, parallel to, or independent of, their chosen religion. Presidents have often served in central roles in civil religion, and the nation provides quasi-religious honors to its martyrs—such as Abraham Lincoln and the soldiers killed in the American Civil War. Historians have noted presidential level use of civil religion rhetoric in profoundly moving episodes such as World War II, the Civil Rights Movement, and the September 11th attacks.

In a survey of more than fifty years of American civil religion scholarship, Squiers identifies fourteen principal tenets of the American civil religion:

This belief system has historically been used to reject nonconformist ideas and groups. Theorists such as Bellah hold that American civil religion can perform the religious functions of integration, legitimation, and prophecy, while other theorists, such as Richard Fenn, disagree.

The concept goes back to the 19th century, but in current form, the theory was developed by sociologist Robert Bellah in 1967 in his article, "Civil Religion in America". The topic soon became the major focus at religious sociology conferences and numerous articles and books were written on the subject. The debate reached its peak with the American Bicentennial celebration in 1976. There is a viewpoint that some Americans have come to see the document of the United States Constitution, along with the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights as cornerstones of a type of civic or civil religion or political religion. Political sociologist Anthony Squiers argues that these texts act as the sacred writ of the American civil religion because they are used as authoritative symbols in what he calls the politics of the sacred. The politics of the sacred, according to Squiers are "the attempt to define and dictate what is in accord with the civil religious sacred and what is not. It is a battle to define what can and cannot be and what should and should not be tolerated and accepted in the community, based on its relation to that which is sacred for that community."

According to Bellah, Americans embrace a common "civil religion" with certain fundamental beliefs, values, holidays, and rituals, parallel to, or independent of, their chosen religion. Presidents have often served in central roles in civil religion, and the nation provides quasi-religious honors to its martyrs—such as Abraham Lincoln and the soldiers killed in the American Civil War. Historians have noted presidential level use of civil religion rhetoric in profoundly moving episodes such as World War II, the Civil Rights Movement, and the September 11th attacks.

In a survey of more than fifty years of American civil religion scholarship, Squiers identifies fourteen principal tenets of the American civil religion:

- Filial piety

- Reverence to certain sacred texts and symbols of the American civil religion (The Constitution, The Declaration of Independence, the flag, etc.)

- The sanctity of American institutions

- The belief in God or a deity

- The idea that rights are divinely given

- The notion that freedom comes from God through government

- Governmental authority comes from God or a higher transcendent authority

- The conviction that God can be known through the American experience

- God is the supreme judge

- God is sovereign

- America's prosperity results from God's providence

- America is a "city on a hill" or a beacon of hope and righteousness

- The principle of sacrificial death and rebirth

- America serves a higher purpose than self-interests

This belief system has historically been used to reject nonconformist ideas and groups. Theorists such as Bellah hold that American civil religion can perform the religious functions of integration, legitimation, and prophecy, while other theorists, such as Richard Fenn, disagree.

Development of concept

Alexis de Tocqueville

believed that Christianity was the source of the basic principles of

liberal democracy, and the only religion capable of maintaining liberty

in a democratic era. He was keenly aware of the mutual hatred between

Christians and liberals in 19th-century France, rooted in the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. In France, Christianity was allied with the Old Regime before 1789 and the reactionary Bourbon Restoration

of 1815-30. However he said Christianity was not antagonistic to

democracy in the United States, where it was a bulwark against dangerous

tendencies toward individualism and materialism, which would lead to atheism and tyranny.

Also important were the contributions of French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917).

The American case

Most students of American civil religion follow the basic Bellah/Durkheimian interpretation. Other sources of this idea include philosopher John Dewey who spoke of "common faith" (1934); sociologist Robin Murphy Williams' American Society: A Sociological Interpretation (1951) which stated there was a "common religion" in America; sociologist Lloyd Warner's analysis of the Memorial Day celebrations in "Yankee City" (1953 [1974]); historian Martin Marty's "religion in general" (1959); theologian Will Herberg who spoke of "the American Way of Life" (1960, 1974); historian Sidney Mead's "religion of the Republic" (1963); and British writer G. K. Chesterton,

who said that the United States was "the only nation ... founded on a

creed" and also coined the phrase "a nation with a soul of a church".

In the same period, several distinguished historians such as Yehoshua Arieli, Daniel Boorstin, and Ralph Gabriel "assessed the religious dimension of 'nationalism', the 'American creed', 'cultural religion' and the 'democratic faith'".

Premier sociologist Seymour Lipset

(1963) referred to "Americanism" and the "American Creed" to

characterize a distinct set of values that Americans hold with a

quasi-religious fervor.

Today, according to social scientist Ronald Wimberley and William

Swatos, there seems to be a firm consensus among social scientists that

there is a part of Americanism that is especially religious in nature,

which may be termed civil religion. But this religious nature is less

significant than the "transcendent universal religion of the nation"

which late eighteenth century French intellectuals such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Alexis de Tocqueville wrote about.

Evidence supporting Bellah

Ronald

Wimberley (1976) and other researchers collected large surveys and

factor analytic studies which gave support to Bellah's argument that

civil religion is a distinct cultural phenomenon within American society

which is not embodied in American politics or denominational religion.

Examples of civil religious beliefs are reflected in statements used in the research such as the following:

- "America is God's chosen nation today."

- "A president's authority ... is from God."

- "Social justice cannot only be based on laws; it must also come from religion."

- "God can be known through the experiences of the American people."

- "Holidays like the Fourth of July are religious as well as patriotic."

- "God Bless America"

Later research sought to determine who is civil religious. In a 1978

study by James Christenson and Ronald Wimberley, the researchers found

that a wide cross section of American citizens have civil religious

beliefs. In general though, college graduates and political or religious

liberals appear to be somewhat less civil religious. Protestants and Catholics have the same level of civil religiosity. Religions that were created in the United States, the Latter Day Saints movement, Adventists, and Pentecostals,

have the highest civil religiosity. Jews, Unitarians and those with no

religious preference have the lowest civil religion. Even though there

is variation in the scores, the "great majority" of Americans are found

to share the types of civil religious beliefs which Bellah wrote about.

Further research found that civil religion plays a role in

people's preferences for political candidates and policy positions. In

1980 Ronald Wimberley found that civil religious beliefs were more

important than loyalties to a political party in predicting support for

Nixon over McGovern with a sample of Sunday morning church goers who

were surveyed near the election date and a general group of residents in

the same community. In 1982 James Christenson and Ronald Wimberley

found that civil religion was second only to occupation in predicting a

person's political policy views.

Coleman has argued that civil religion is a widespread theme in

history. He says it typically evolves in three phases:

undifferentiation, state sponsorship in the period of modernization,

differentiation. He supports his argument with comparative historical

data from Japan, Imperial Rome, the Soviet Union, Turkey, France and The

United States.

Civil religion in practice

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the main source of civil religion. It produced a Moses-like leader (George Washington), prophets (Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine), apostles (John Adams, Benjamin Franklin) and martyrs (Boston Massacre, Nathan Hale), as well as devils (Benedict Arnold), sacred places (Valley Forge), rituals (raising the Liberty Tree), flags (the Betsy Ross flag), sacred holidays (July 4th) and a holy scripture (The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution).

Ceremonies in the early Republic

The Apotheosis of Washington, as seen looking up from the capitol rotunda

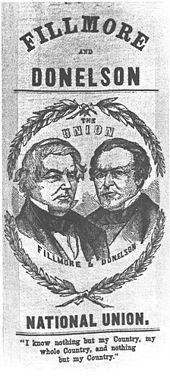

The elitists who ran the Federalists were conscious of the need to boost voter identification with their party.

Elections remained of central importance but for the rest of the

political year celebrations, parades, festivals, and visual

sensationalism were used. They employed multiple festivities, exciting

parades, and even quasi-religious pilgrimages and "sacred" days that

became incorporated into the American civil religion. George Washington

was always its hero, and after his death he became a sort of demigod looking down from heaven to instill his blessings on the party.

At first the Federalists focused on commemoration of the

ratification of the Constitution; they organized parades to demonstrate

widespread popular support for the new Federalist Party. The parade

organizers, incorporated secular versions of traditional religious

themes and rituals, thereby fostering a highly visible celebration of

the nation's new civil religion.

The Fourth of July became a semi-sacred day—a status it maintains

in the 21st century. Its celebration in Boston proclaimed national

over local patriotism, and included orations, dinners, militia

musters, parades, marching bands, floats and fireworks. By 1800, the

Fourth was closely identified with the Federalist party. Republicans

were annoyed, and stage their own celebrations on the fourth—with rival

parades sometimes clashing with each other. That generated even more

excitement and larger crowds. After the collapse of the Federalists

starting in 1815, the Fourth became a nonpartisan holiday.

President as leader of civil religion

Since

the days of George Washington presidents have assumed one of several

roles in American civil religion, and that role has helped shape the

presidency. Linder argues that:

Throughout American history, the president has provided the leadership in the public faith. Sometimes he has functioned primarily as a national prophet, as did Abraham Lincoln. Occasionally he has served primarily as the nation's pastor, as did Dwight Eisenhower. At other times he has performed primarily as the high priest of the civil religion, as did Ronald Reagan. In prophetic civil religion, the president assesses the nation's actions in relation to transcendent values and calls upon the people to make sacrifices in times of crisis and to repent of their corporate sins when their behavior falls short of the national ideals. As the national pastor, he provides spiritual inspiration to the people by affirming American core values and urging them to appropriate those values, and by comforting them in their afflictions. In the priestly role, the president makes America itself the ultimate reference point. He leads the citizenry in affirming and celebrating the nation, and reminds them of the national mission, while at the same time glorifying and praising his political flock.

Charles W. Calhoun argues that in the 1880s the speeches of Benjamin Harrison

display a rhetorical style that embraced American civic religion;

indeed, Harrison was one of the credo's most adept presidential

practitioners. Harrison was a leader whose application of Christian

ethics to social and economic matters paved the way for the Social Gospel, the Progressive Movement and a national climate of acceptance regarding government action to resolve social problems.

Linder argues that President Bill Clinton's sense of civil religion was based on his Baptist background in Arkansas. Commentator William Safire

noted of the 1992 presidential campaign that, "Never has the name of

God been so frequently invoked, and never has this or any nation been so

thoroughly and systematically blessed."

Clinton speeches incorporated religious terminology that suggests the

role of pastor rather than prophet or priest. With a universalistic

outlook, he made no sharp distinction between the domestic and the

foreign in presenting his vision of a world community of civil faith.

Brocker argues that Europeans have often mischaracterized the politics of President George W. Bush (2001–2009) as directly inspired by Protestant fundamentalism.

However, in his speeches Bush mostly actually used civil religious

metaphors and images and rarely used language specific to any Christian

denomination. His foreign policy, says Bocker, was based on American security interests and not on any fundamentalist teachings.

Hammer says that in his 2008 campaign speeches candidate Barack Obama

portrays the American nation as a people unified by a shared belief in

the American Creed and sanctified by the symbolism of an American civil

religion.

Would-be presidents likewise contributed to the rhetorical history of civil religion. The speeches of Daniel Webster

were often memorized by student debaters, and his 1830 endorsement of

"Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable" was iconic.

Symbolism of the American flag

According to Adam Goodheart, the modern meaning of the American flag, and the reverence of many Americans towards it, was forged by Major Robert Anderson's fight in defense of the flag at the Battle of Fort Sumter, which opened the American Civil War

in April 1861. During the war the flag was used throughout the Union to

symbolize American nationalism and rejection of secessionism. Goodheart

explains the flag was transformed into a sacred symbol of patriotism:

Before that day, the flag had served mostly as a military ensign or a convenient marking of American territory ... and displayed on special occasions like the Fourth of July. But in the weeks after Major Anderson's surprising stand, it became something different. Suddenly the Stars and Stripes flew ... from houses, from storefronts, from churches; above the village greens and college quads. ... [T]hat old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union cause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for.

Soldiers and veterans

An

important dimension is the role of the soldiers, ready to sacrifice

their lives to preserve the nation. They are memorialized in many

monuments and semi-sacred days, such as Veterans Day and Memorial Day.

Historian Jonathan Ebel argues that the "soldier-savior" is a sort of

Messiah, who embodies the synthesis of civil religion, and the Christian

ideals of sacrifice and redemption.

In Europe, there are numerous cemeteries exclusively for American

soldiers who fought in world wars. They have become American sacred

spaces.

Pacifists have made some sharp criticisms. For example, Kelly Denton-Borhaug, writing from the Moravian peace tradition,

argues that the theme of "sacrifice" has fueled the rise of what she

calls "U.S. war culture." The result is a diversion of attention from

what she considers the militarism and the immoral, oppressive, sometimes

barbaric conduct in the global American war on terror. However, some Protestant denominations such as the Churches of Christ, have largely turned away from pacifism to give greater support to patriotism and civil religion.

Pledge of Allegiance

Kao and Copulsky argue the concept of civil religion illuminates the popular constitutional debate over the Pledge of Allegiance.

The function of the pledge has four aspects: preservationist,

pluralist, priestly, and prophetic. The debate is not between those who

believe in God and those who do not, but it is a dispute on the meaning

and place of civil religion in America.

Cloud explores political oaths since 1787 and traces the tension

between a need for national unity and a desire to affirm religious

faith. He reviews major Supreme Court decisions involving the Pledge of Allegiance, including the contradictory Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) and West Virginia v. Barnette

(1943) decisions. He argues that the Pledge was changed in 1954 during

the Cold War to encourage school children to reject communism's

atheistic philosophy by affirming belief in God.

School rituals

Adam Gamoran

(1990) argues that civil religion in public schools can be seen in such

daily rituals as the pledge of allegiance; in holiday observances, with

activities such as music and art; and in the social studies, history

and English curricula. Civil religion in schools plays a dual role: it

socializes youth to a common set of understandings, but it also sets off

subgroups of Americans whose backgrounds or beliefs prevent them from

participating fully in civil religious ceremonies.

Ethnic minorities

The

Bellah argument deals with mainstream beliefs, but other scholars have

looked at minorities outside the mainstream, and typically distrusted or

disparaged by the mainstream, which have developed their own version of

U.S. civil religion.

White Southerners

Wilson, noting the historic centrality of religion in Southern identity, argues that when the White South

was outside the national mainstream in the late 19th century, it

created its own pervasive common civil religion heavy with mythology,

ritual, and organization. Wilson says the "Lost Cause"—that

is, defeat in a holy war—has left some southerners to face guilt,

doubt, and the triumph of what they perceive as evil: in other words, to

form a tragic sense of life.

Black and African Americans

Woodrum and Bell argue that black people demonstrate less civil religiosity than white people

and that different predictors of civil religion operate among black and

white people. For example, conventional religion positively influences

white people's civil religion but negatively influences black peoples'

civil religion. Woodrum and Bell interpret these results as a product of

black American religious ethnogenesis and separatism.

Japanese Americans

Iwamura argues that the pilgrimages made by Japanese Americans to the sites of World War II-era internment camps

have formed a Japanese American version of civil religion. Starting in

1969 the Reverend Sentoku Maeda and Reverend Soichi Wakahiro began

pilgrimages to Manzanar National Historic Site

in California. These pilgrimages included poetry readings, music,

cultural events, a roll call of former internees, and a

nondenominational ceremony with Protestant and Buddhist ministers and Catholic and Shinto

priests. The event is designed to reinforce Japanese American cultural

ties and to ensure that such injustices will never occur again.

Hispanic and Latino Americans

Mexican-American labor leader César Chávez,

by virtue of having holidays, stamps, and other commemorations of his

actions, has practically become a "saint" in American civil religion,

according to León. He was raised in the Catholic tradition and using

Catholic rhetoric. His "sacred acts," his political practices couched in

Christian teachings, became influential to the burgeoning Chicano

movement and strengthened his appeal. By acting on his moral convictions

through nonviolent means, Chávez became sanctified in the national

consciousness, says León.

Enshrined texts

Christian language, rhetoric, and values helped colonists to perceive

their political system as superior to the corrupt British monarchy.

Ministers' sermons were instrumental in promoting patriotism and in

motivating the colonists to take action against the evils and corruption

of the British government. Together with the semi-religious tone

sometimes adopted by preachers and such leaders as George Washington, and the notion that God favored the patriot cause, this made the documents of the Founding Fathers suitable as almost-sacred texts.

The National Archives Building in Washington preserves and displays the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Pauline Maier describes these texts as enshrined in massive, bronze-framed display cases.

While political scientists, sociologists, and legal scholars study the

Constitution and how it is used in American society, on the other hand,

historians are concerned with putting themselves back into a time and

place, in context. It would be anachronistic for them to look at the

documents of the "Charters of Freedom" and see America's modern "civic

religion" because of "how much Americans have transformed very secular

and temporal documents into sacred scriptures".

The whole business of erecting a shrine for the worship of the

Declaration of Independence strikes some academic critics looking from

point of view of the 1776 or 1789 America as "idolatrous, and also

curiously at odds with the values of the Revolution." It was suspicious

of religious iconographic practices. At the beginning, in 1776, it was

not meant to be that at all.

On the 1782 Great Seal of the United States,

the date of the Declaration of Independence and the words under it

signify the beginning of the "new American Era" on earth. Though the

inscription, Novus ordo seclorum, does not translate from the

Latin as "secular", it also does not refer to a new order of heaven. It

is a reference to generations of society in the western hemisphere, the

millions of generations to come.

Even from the vantage point of a new nation only ten to twenty

years after the drafting of the Constitution, the Framers themselves

differed in their assessments of its significance. Washington in his

Farewell Address pleaded that "the Constitution be sacredly

maintained."' He echoed Madison in "Federalist No. 49"

that citizen "veneration" of the Constitution might generate the

intellectual stability needed to maintain even the "wisest and freest

governments" amidst conflicting loyalties. But there is also a rich

tradition of dissent from "Constitution worship". By 1816, Jefferson

could write that "some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious

reverence and deem them like the ark of the covenant,

too sacred to be touched." But he saw imperfections and imagined that

potentially, there could be others, believing as he did that

"institutions must advance also".

Regarding the United States Constitution, the position of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is that it is a divinely inspired document.

Seventh-Day Adventists

While the civil religion has been widely accepted by practically all denominations, one group has always stood against it. Seventh-Day Adventists

deliberately pose as "heretics", so to speak, and refuse to treat

Sundays as special, due to their adherence to the Ten Commandments

dictating that Saturday is the holy day. Indeed, says Bull, the

denomination has defined its identity in contradistinction to precisely

those elements of the host culture that have constituted civil religion.

Making a nation

The American identity has an ideological connection to these "Charters of Freedom". Samuel P. Huntington

discusses common connections for most peoples in nation-states, a

national identity as product of common ethnicity, ancestry and

experience, common language, culture and religion. Levinson argues:

It is the fate of the United States, however, to be different from "most peoples," for here national identity is based not on shared Proustian remembrances, but rather on the willed affirmation of what Huntington refers to as the "American creed," a set of overt political commitments that includes an emphasis on individual rights, majority rule, and a constitutional order limiting governmental power.

The creed, according to Huntington, is made up of (a) individual

rights, (b) majority rule, and (c) a constitutional order of limited

government power. American independence from Britain was not based on

cultural difference, but on the adoption of principles found in the

Declaration. Whittle Johnson in The Yale Review

sees a sort of "covenanting community" of freedom under law, which,

"transcending the 'natural' bonds of race, religion and class, itself

takes on transcendent importance".

Becoming a naturalized citizen of the United States requires

passing a test covering a basic understanding of the Declaration, the

U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and taking an oath to support

the U.S. Constitution. Hans Kohn

described the United States Constitution as "unlike any other: it

represents the lifeblood of the American nation, its supreme symbol and

manifestation. It is so intimately welded with the national existence

itself that the two have become inseparable." Indeed, abolishing the

Constitution in Huntington's view would abolish the United States, it

would "destroy the basis of community, eliminating the nation,

[effecting] ... a return to nature."

As if to emphasize the lack of any alternative "faith" to the

American nation, Thomas Grey in his article "The Constitution as

scripture", contrasted those traditional societies with divinely

appointed rulers enjoying heavenly mandates for social cohesion with

that of the United States. He pointed out that Article VI, third clause,

requires all political figures, both federal and state, "be bound by

oath or affirmation to support this Constitution, but no religious test

shall ever be required ..." This was a major

break not only with past British practice commingling authority of

state and religion, but also with that of most American states when the

Constitution was written.

Escape clause. Whatever the oversights and evils the

modern reader may see in the original Constitution, the Declaration that

"all men are created equal"—in their rights—informed the Constitution

in such a way that Frederick Douglass in 1860 could label the Constitution, if properly understood, as an antislavery document.

He held that "the constitutionality of slavery can be made out only by

disregarding the plain and common-sense reading to the Constitution

itself. [T]he Constitution will afford slavery no protection when it

shall cease to be administered by slaveholders," a reference to the

Supreme Court majority at the time.

With a change of that majority, there was American precedent for

judicial activism in Constitutional interpretation, including the

Massachusetts Supreme Court, which had ended slavery there in 1783.

Accumulations of Amendments under Article V of the Constitution

and judicial review of Congressional and state law have fundamentally

altered the relationship between U.S. citizens and their governments.

Some scholars refer to the coming of a "second Constitution" with the Thirteenth Amendment, we are all free, the Fourteenth, we are all citizens, the Fifteenth, men vote, and the Nineteenth,

women vote. The Fourteenth Amendment has been interpreted so as to

require States to respect citizen rights in the same way that the

Constitution has required the Federal government to respect them. So

much so, that in 1972, the U.S. Representative from Texas, Barbara Jordan, could affirm, "My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total ...".

After discussion of the Article V provision for change in the Constitution as a political stimulus to serious national consensus building, Sanford Levinson

performed a thought experiment which was suggested at the bicentennial

celebration of the Constitution in Philadelphia. If one were to sign the

Constitution today,

whatever our reservations might be, knowing what we do now, and

transported back in time to its original shortcomings, great and small,

"signing the Constitution commits one not to closure but only to a

process of becoming, and to taking responsibility for the political

vision toward which I, joined I hope, with others, strive."