Medievalism is a system of belief and practice inspired by the Middle Ages of Europe, or by devotion to elements of that period, which have been expressed in areas such as architecture, literature, music, art, philosophy, scholarship, and various vehicles of popular culture. Since the 17th century, a variety of movements have used the medieval period as a model or inspiration for creative activity, including Romanticism, the Gothic revival, the pre-Raphaelite and arts and crafts movements, and neo-medievalism (a term often used interchangeably with medievalism).

Renaissance to Enlightenment

In the 1330s, Petrarch expressed the view that European culture had stagnated and drifted into what he called the "Dark Ages", since the fall of Rome in the fifth century, owing to among other things, the loss of many classical Latin texts and to the corruption of the language in contemporary discourse. Scholars of the Renaissance believed that they lived in a new age that broke free of the decline described by Petrarch. Historians Leonardo Bruni and Flavio Biondo developed a three tier outline of history composed of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. The Latin term media tempestas (middle time) first appears in 1469. The term medium aevum (Middle Ages) is first recorded in 1604. "Medieval" first appears in the nineteenth century and is an Anglicised form of medium aevum.

During the Reformations of the 16th and 17th centuries, Protestants generally followed the critical views expressed by Renaissance Humanists, but for additional reasons. They saw classical antiquity as a golden time, not only because of Latin literature, but because it was the early beginnings of Christianity. The intervening 1000 year Middle Age was a time of darkness, not only because of lack of secular Latin literature, but because of corruption within the Church such as Popes who ruled as kings, pagan superstitions with saints' relics, celibate priesthood, and institutionalized moral hypocrisy. Most Protestant historians did not date the beginnings of the modern era from the Renaissance, but later, from the beginnings of the Reformation.

In the Age of Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, the Middle Ages was seen as an "Age of Faith" when religion reigned, and thus as a period contrary to reason and contrary to the spirit of the Enlightenment. For them the Middle Ages was barbaric and priest-ridden. They referred to "these dark times", "the centuries of ignorance", and "the uncouth centuries". The Protestant critique of the Medieval Church was taken into Enlightenment thinking by works including Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–89). Voltaire was particularly energetic in attacking the religiously dominated Middle Ages as a period of social stagnation and decline, condemning Feudalism, Scholasticism, The Crusades, The Inquisition and the Catholic Church in general.

Gothic revival

The Gothic Revival was an architectural movement which began in the 1740s in England. Its popularity grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, when increasingly serious and learned admirers of neo-Gothic styles sought to revive medieval forms in contrast to the classical styles prevalent at the time. In England, the epicentre of this revival, it was intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with a re-awakening of "High Church" or Anglo-Catholic self-belief (and by the Catholic convert Augustus Welby Pugin) concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism. He went on to produce important Gothic buildings such as Cathedrals at Birmingham and Southwark and the British Houses of Parliament in the 1840s. Large numbers of existing English churches had features such as crosses, screens and stained glass (removed at the Reformation), restored or added, and most new Anglican and Catholic churches were built in the Gothic style. Viollet-le-Duc was a leading figure in the movement in France, restoring the entire walled city of Carcassonne as well as Notre-Dame and Sainte Chapelle in Paris. In America Ralph Adams Cram was a leading force in American Gothic, with his most ambitious project the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York (one of the largest cathedrals in the world), as well as Collegiate Gothic buildings at Princeton Graduate College. On a wider level the wooden Carpenter Gothic churches and houses were built in large numbers across North America in this period.

In English literature, the architectural Gothic Revival and classical Romanticism gave rise to the Gothic novel, often dealing with dark themes in human nature against medieval backdrops and with elements of the supernatural. Beginning with The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford, it also included Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and John Polidori's The Vampyre (1819), which helped found the modern horror genre. This helped create the dark romanticism or American Gothic of authors like Edgar Allan Poe in works including "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) and "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1842) and Nathanial Hawthorne in "The Minister's Black Veil" (1836) and "The Birth-Mark" (1843). This in turn influenced American novelists like Herman Melville in works such as Moby-Dick (1851). Early Victorian Gothic novels included Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1847) and Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847). The genre was revived and modernised toward the end of the century with works like Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) and Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897).

Romanticism

Romanticism was a complex artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the eighteenth century in Western Europe, and gained strength during and after the Industrial and French Revolutions. It was partly a revolt against the political norms of the Age of Enlightenment which rationalised nature, and was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature. Romanticism has been seen as "the revival of the life and thought of the Middle Ages", reaching beyond rational and Classicist models to elevate medievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval, in an attempt to escape the confines of population growth, urban sprawl and industrialism, embracing the exotic, unfamiliar and distant.

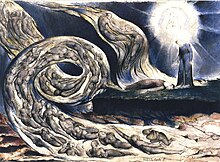

The name "Romanticism" itself was derived from the medieval genre chivalric romance. This movement contributed to the strong influence of such romances, disproportionate to their actual showing among medieval literature, on the image of Middle Ages, such that a knight, a distressed damsel, and a dragon is used to conjure up the time pictorially. The Romantic interest in the medieval can particularly be seen in the illustrations of English poet William Blake and the Ossian cycle published by Scottish poet James Macpherson in 1762, which inspired both Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen (1773), and the young Walter Scott. The latter's Waverley Novels, including Ivanhoe (1819) and Quentin Durward (1823) helped popularise, and shape views of, the medieval era. The same impulse manifested itself in the translation of medieval national epics into modern vernacular languages, including Nibelungenlied (1782) in Germany, The Lay of the Cid (1799) in Spain, Beowulf (1833) in England, The Song of Roland (1837) in France, which were widely read and highly influential on subsequent literary and artistic work.

The Nazarenes

The name Nazarene was adopted by a group of early nineteenth-century German Romantic painters who reacted against Neoclassicism and hoped to return to art which embodied spiritual values. They sought inspiration in artists of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, rejecting what they saw as the superficial virtuosity of later art. The name Nazarene came from a term of derision used against them for their affectation of a biblical manner of clothing and hair style. The movement was originally formed in 1809 by six students at the Vienna Academy and called the Brotherhood of St. Luke or Lukasbund, after the patron saint of medieval artists. In 1810 four of them, Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr, Ludwig Vogel and Johann Konrad Hottinger moved to Rome, where they occupied the abandoned monastery of San Isidoro and were joined by Philipp Veit, Peter von Cornelius, Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld, Friedrich Wilhelm Schadow and a loose grouping of other German artists. They met up with Austrian romantic landscape artist Joseph Anton Koch (1768–1839) who became an unofficial tutor to the group and in 1827 they were joined by Joseph von Führich (1800–76). In Rome the group lived a semi-monastic existence, as a way of re-creating the nature of the medieval artist's workshop. Religious subjects dominated their output and two major commissions for the Casa Bartholdy (1816–17) (later moved to the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin) and the Casino Massimo (1817–29), allowed them to attempt a revival of the medieval art of fresco painting and gained then international attention. However, by 1830 all except Overbeck had returned to Germany and the group had disbanded. Many Nazareners became influential teachers in German art academies and were a major influence on the later English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Social commentary

Eventually, medievalism moved from the confines of fiction into the immediate realm of social commentary as means of critiquing life in the Industrial Era. An early work of this kind is William Cobbett's History of the Protestant Reformation (1824–6), which was influenced by his reading of John Lingard's History of England (1819–30), among other sources. Cobbett attacked the Reformation as having divided a once-unified and wealthy England into "masters and slaves, a very few enjoying the extreme of luxury, and millions doomed to the extreme of misery", while decrying how "this land of meat and beef was changed, all of a sudden into a land of dry bread and oatmeal porridge". In the Victorian era, the principal representatives of this school were Thomas Carlyle and his disciple John Ruskin.

In Carlyle's Past and Present (1843), which Oliver Elton called the "most remarkable fruit in English literature of the medieval revival", the modern workhouse is contrasted with the medieval monastery. He draws on Jocelyn de Brakelond's twelfth-century account of Samson of Tottington's abbotcy of Bury St Edmunds Abbey to call for a "Chivalry of Labour" based on cooperation and fraternity rather than competition and "Cash-payment for the sole nexus", and for the leadership of paternalistic "Captains of Industry".

Ruskin connected the quality of a nation's architecture with its spiritual health, comparing the originality and freedom of medieval art with the mechanistic sterility of modernism in such works as Modern Painters, Volume II (1846), The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1851–3). At the urging of Carlyle, Ruskin, who identified as both a "violent Tory of the old school" and a "Communist of the old school", adapted this thesis to his theory of political economy in Unto This Last (1860), and to his "Ideal Commonwealth" in Time and Tide (1867), the characteristics of which were derived from the Middle Ages: the guild system, the feudal system, chivalry, and the church.

The Pre-Raphaelites

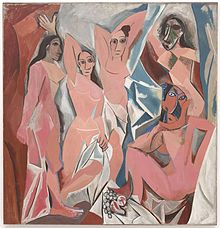

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of English painters, poets, and critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The three founders were soon joined by William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner to form a seven-member "brotherhood". The group's intention was to reform art by rejecting what they considered to be the mechanistic approach first adopted by the Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. They believed that the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art. Hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite". In particular, they objected to the influence of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founder of the English Royal Academy of Arts, believing that his broad technique was a sloppy and formulaic form of academic Mannerism. In contrast, they wanted to return to the abundant detail, intense colours, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art.

The arts and crafts movement

The arts and crafts movement was an aesthetic movement, directly influenced by the Gothic revival and the Pre-Raphaelites, but moving away from aristocratic, nationalist and high Gothic influences to an emphasis on the idealised peasantry and medieval community, particularly of the fourteenth century, often with socialist political tendencies and reaching its height between about 1880 and 1910. The movement was inspired by the writings of Carlyle and Ruskin and was spearheaded by the work of William Morris, a friend of the Pre-Raphaelites and a former apprentice to Gothic-revival architect G. E. Street. He focused on the fine arts of textiles, wood and metal work and interior design. Morris also produced medieval and ancient themed poetry, beside socialist tracts and the medieval Utopia News From Nowhere (1890). Morris formed Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in 1861, which produced and sold furnishings and furniture, often with medieval themes, to the emerging middle classes. The first arts and crafts exhibition in the United States was held in Boston in 1897 and local societies spread across the country, dedicated to preserving and perfecting disappearing craft and beautifying house interiors. Whereas the Gothic revival had tended to emulate ecclesiastical and military architecture, the arts and crafts movement looked to rustic and vernacular medieval housing. The creation of aesthetically pleasing and affordable furnishings proved highly influential on subsequent artistic and architectural developments.

Romantic nationalism

By the late nineteenth century real and pseudo-medieval symbols were a currency of European monarchical state propaganda. German emperors dressed up in and proudly displayed medieval costumes in public, and they rebuilt the great medieval castle and spiritual home of the Teutonic Order at Marienburg. Ludwig II of Bavaria built a fairy-tale castle at Neuschwanstein and decorated it with scenes from Wagner's operas, another major Romantic image maker of the Middle Ages. The same imagery would be used in Nazi Germany in the mid-twentieth century to promote German national identity with plans for extensive building in the medieval style and attempts to revive the virtues of the Teutonic knights, Charlemagne and the Round Table.

In England, the Middle Ages were trumpeted as the birthplace of democracy because of the Magna Carta of 1215. In the reign of Queen Victoria there was considerable interest in things medieval, particularly among the ruling classes. The notorious Eglinton Tournament of 1839 attempted to revive the medieval grandeur of the monarchy and aristocracy. Medieval fancy dress became common in this period at royal and aristocratic masquerades and balls and individuals and families were painted in medieval costume. These trends inspired a nineteenth-century genre of medieval poetry that included Idylls of the King (1842) by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson and "The Sword of Kingship" (1866) by Thomas Westwood, which recast specifically modern themes in the medieval settings of Arthurian romance.

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

Popular culture

Historians have attempted to conceptualize the history of non-European countries in terms of medievalisms, but the approach has been controversial among scholars of Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

Film

Film has been one of the most significant creators of images of the Middle Ages since the early twentieth century. The first medieval film was also one of the earliest films ever made, about Jeanne d'Arc in 1899, while the first to deal with Robin Hood dates to as early as 1908. Influential European films, often with a nationalist agenda, included the German Nibelungenlied (1924), Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Bergman's The Seventh Seal (1957), while in France there were many Joan of Arc sequels. Hollywood adopted the medieval as a major genre, issuing periodic remakes of the King Arthur, William Wallace and Robin Hood stories, adapting to the screen such historical romantic novels as Ivanhoe (1952—by MGM), and producing epics in the vein of El Cid (1961). More recent revivals of these genres include Robin Hood Prince of Thieves (1991), The 13th Warrior (1999) and The Kingdom of Heaven (2005).

Fantasy

While the folklore that fantasy drew on for its magic and monsters was not exclusively medieval, elves, dragons, and unicorns, among many other creatures, were drawn from medieval folklore and romance. Earlier writers in the genre, such as George MacDonald in The Princess and the Goblin (1872), William Morris in The Well at the World's End (1896) and Lord Dunsany in The King of Elfland's Daughter (1924), set their tales in fantasy worlds clearly derived from medieval sources, though often filtered through later views. In the first half of the twentieth century pulp fiction writers like Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith helped popularise the sword and sorcery branch of fantasy, which often utilised prehistoric and non-European settings beside elements of the medieval. In contrast, authors such as E. R. Eddison and particularly J.R.R. Tolkien, set the type for high fantasy, normally based in a pseudo-medieval setting, mixed with elements of medieval folklore. Other fantasy writers have emulated such elements, and films, role-playing and computer games also took up this tradition. Modern fantasy writers have taken elements of the medieval from these works to produce some of the most commercially successful works of fiction of recent years, sometimes pointing to the absurdities of the genre, as in Terry Pratchett's Discworld novels, or mixing it with the modern world as in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter books.

Living history

In the second half of the twentieth century interest in the medieval was increasingly expressed through form of re-enactment, including combat reenactment, re-creating historical conflict, armour, arms and skill, as well as living history which re-creates the social and cultural life of the past, in areas such as clothing, food and crafts. The movement has led to the creation of medieval markets and Renaissance fairs, from the late 1980s, particularly in Germany and the United States of America.

Neo-medievalism

Neo-medievalism (or neomedievalism) is a neologism that was first popularized by the Italian medievalist Umberto Eco in his 1973 essay "Dreaming of the Middle Ages". The term has no clear definition but has since been used to describe the intersection between popular fantasy and medieval history as can be seen in computer games such as MMORPGs, films and television, neo-medieval music, and popular literature. It is in this area—the study of the intersection between contemporary representation and past inspiration(s)—that medievalism and neomedievalism tend to be used interchangeably. Neomedievalism has also been used as a term describing the post-modern study of medieval history and as a term for a trend in modern international relations, first discussed in 1977 by Hedley Bull, who argued that society was moving towards a form of "neomedievalism" in which individual notions of rights and a growing sense of a "world common good" were undermining national sovereignty.

The study of medievalism

Leslie J. Workman, Kathleen Verduin and David Metzger noted in their introduction to Studies in Medievalism IX "Medievalism and the Academy, Vol I" (1997) their sense that medievalism had been perceived by some medievalists as a "poor and somewhat whimsical relation of (presumably more serious) medieval studies". In The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism (2016), editor Louise D'Arcens noted that some of the earliest medievalism scholarship (that is, study of the phenomenon of medievalism) was by Victorian specialists including Alice Chandler (with her monograph A Dream of Order: The Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth Century England (London: Taylor and Francis, 1971), and Florence Boos, with her edited volume History and Community: Essays in Victorian Medievalism (London: Garland Publishing, 1992)). D'Arcens proposed that the 1970s saw the discipline of medievalism become an academic area of research in its own right, with the International Society for the Study of Medievalism formalised in 1979 with the publication of its Studies In Medievalism journal, organised by Leslie J. Workman. D'Arcens notes that by 2016 medievalism was taught as a subject on "hundreds" of university courses around the world, and there were "at least two" scholarly journals dedicated to medievalism studies: Studies in Medievalism and postmedieval.

Clare Monagle has argued that political medievalism has caused medieval scholars to repeatedly reconsider whether medievalism is a part of the study of the Middle Ages as a historical period. Monagle explains how in 1977 the International Relations scholar Hedley Bull coined the term "New Medievalism" to describe the world as a result of the rising powers of non-state actors in society (such as terrorist groups, corporations, or supra-state organisations such as the European Economic Community) which, due to new technologies, boundaries of jurisdiction that cross national borders, and shifts in private wealth challenged the exclusive authority of the state. Monagle explained that in 2007 medieval scholar Bruce Holsinger published Neomedievalism, Conservativism and the War on Terror, which identified how George W. Bush's administration relied on medievalising rhetoric to identify al-Qaeda as "dangerously fluid, elusive, and stateless". Monagle documents how Gabrielle Spiegel, then president of the American Historical Society "expressed concern at the idea that scholars of the historical medieval period might consider themselves licensed to in some way to intervene in contemporary medievalism", as to do so "conflates two very different historical periods". Eileen Joy (co-founder and co-editor of the postmedieval journal), responded to Spiegel that "the idea of a medieval past itself, as something that can be demarcated and cordoned off from other historical time periods, was and is of itself [...] a form of medievalism. Therefore, practising medievalists should absolutely pay heed to the use and abuse of the Middle Ages in contemporary discourse".

Medievalism topics are now annual features at the major medieval conferences the International Medieval Congress hosted at the University of Leeds, UK, and the International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo, Michigan.