A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small. Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.

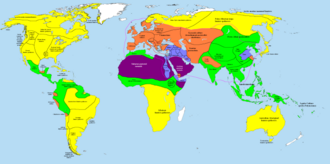

While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state, though in some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.

Some political philosophies, particularly anarchism, consider the state an unwelcome institution and stateless societies the ideal, while Marxism considers that in a post-capitalist society, the state would be unnecessary and wither away.

Prehistoric peoples

In archaeology, cultural anthropology and history, a stateless society denotes a less complex human community without a state, such as a tribe, a clan, a band society or a chiefdom. The main criterion of "complexity" used is the extent to which a division of labor has occurred such that many people are permanently specialized in particular forms of production or other activity, and depend on others for goods and services through trade or sophisticated reciprocal obligations governed by custom and laws. An additional criterion is population size. The bigger the population, the more relationships have to be reckoned with.

Evidence of the earliest known city-states has been found in ancient Mesopotamia around 3700 BCE, suggesting that the history of the state is less than 6,000 years old; thus, for most of human prehistory the state did not exist.

For 99.8 percent of human history people lived exclusively in autonomous bands and villages. At the beginning of the Paleolithic [i.e. the Stone Age], the number of these autonomous political units must have been small, but by 1000 BCE it had increased to some 600,000. Then supra-village aggregation began in earnest, and in barely three millennia the autonomous political units of the world dropped from 600,000 to 157.

— Robert L. Carneiro, 1978

Generally speaking, the archaeological evidence suggests that the state emerged from stateless communities only when a fairly large population (at least tens of thousands of people) was more or less settled together in a particular territory, and practiced agriculture. Indeed, one of the typical functions of the state is the defense of territory. Nevertheless, there are exceptions: Lawrence Krader for example describes the case of the Tatar state, a political authority arising among confederations of clans of nomadic or semi-nomadic herdsmen.

Characteristically the state functionaries (royal dynasties, soldiers, scribes, servants, administrators, lawyers, tax collectors, religious authorities etc.) are mainly not self-supporting, but rather materially supported and financed by taxes and tributes contributed by the rest of the working population. This assumes a sufficient level of labor-productivity per capita which at least makes possible a permanent surplus product (principally foodstuffs) appropriated by the state authority to sustain the activities of state functionaries. Such permanent surpluses were generally not produced on a significant scale in smaller tribal or clan societies.

The archaeologist Gregory Possehl has argued that there is no evidence that the relatively sophisticated, urbanized Harappan civilization, which flourished from about 2,500 to 1,900 BCE in the Indus region, featured anything like a centralized state apparatus. No evidence has yet been excavated locally of palaces, temples, a ruling sovereign or royal graves, a centralized administrative bureaucracy keeping records, or a state religion—all of which are elsewhere usually associated with the existence of a state apparatus. However, there is no recent scholarly consensus agreeing with that perspective, as more recent literature has suggested that there may have been less conspicuous forms of centralisation, as Harappan cities were centred around public ceremonial places and large spaces interpreted as ritual complexes. Additionally, recent interpretations of the Indus Script and Harappan stamps indicate that there was a somewhat centralised system of economic record keeping. It remains impossible to judge for now as the Harappan civilization's writing system remains undeciphered. One study summarised it best, “Many sites have been excavated that belong to the Indus Valley civilization, but it remains unresolved whether it was a state, a number of kingdoms, or a stateless commonwealth. So few written documents on this early civilization have been preserved that it seems unlikely that this and other questions will ever be answered.”

In the earliest large-scale human settlements of the Stone Age which have been discovered, such as Çatal Höyük and Jericho, no evidence was found of the existence of a state authority. The Çatal Höyük settlement of a farming community (7,300 BCE to c. 6,200 BCE) spanned circa 13 hectares (32 acres) and probably had about 5,000 to 10,000 inhabitants.

Modern state-based societies regularly pushed out stateless indigenous populations as their settlements expanded, or attempted to make those populations come under the control of a state structure. This was particularly the case on the African continent during European colonisation, where there was much confusion about the best way to govern societies who, prior to European arrival, had been stateless. Tribal societies, on first glance appearing to be chaotic, often had well-organised societal structures that were based on multiple undefined cultural factors – including the ownership of cattle and arable land, patrilineal descent structures, honour gained from success in conflict etc.

Uncontacted peoples may be considered remnants of prehistoric stateless societies. To varying extents they may be unaware of and unaffected by the states that have nominal authority over their territory.

As a political ideal

Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved.

A central tenet of anarchism is the advocacy of society without states. The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought, ranging from extreme individualism to complete collectivism. Anarcho-capitalism opposes the state while supporting private institutions.

In Marxism, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and wither away. A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society.

Social and economic organization

Anthropologists have found that social stratification is not the standard among all societies. John Gowdy writes, "Assumptions about human behaviour that members of market societies believe to be universal, that humans are naturally competitive and acquisitive, and that social stratification is natural, do not apply to many hunter-gatherer peoples."

The economies of stateless agricultural societies tend to focus and organize subsistence agriculture at the community level, and tend to diversify their production rather than specializing in a particular crop.

In many stateless societies, conflicts between families or individuals are resolved by appealing to the community. Each of the sides of the dispute will voice their concerns, and the community, often voicing its will through village elders, will reach a judgment on the situation. Even when there is no legal or coercive authority to enforce these community decisions, people tend to adhere to them, due to a desire to be held in esteem by the community.