The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emphasize alcohol's negative effects on people's health, personalities and family lives. Typically the movement promotes alcohol education and it also demands the passage of new laws against the sale of alcohol, either regulations on the availability of alcohol, or the complete prohibition of it. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the temperance movement became prominent in many countries, particularly in English-speaking, Scandinavian, and majority Protestant ones, and it eventually led to national prohibitions in Canada (1918 to 1920), Norway (spirits only from 1919 to 1926), Finland (1919 to 1932), and the United States (1920 to 1933), as well as provincial prohibition in India (1948 to present). A number of temperance organizations exist that promote temperance and teetotalism as a virtue.

Context

In late 17th-century North America, alcohol was a vital part of colonial life as a beverage, medicine, and commodity for men, women, and children. Drinking was widely accepted and completely integrated into society; however, drunkenness was not tolerated. In colonial period of America from around 1623, when a Plymouth minister named William Blackstone began distributing apples and flowers, up until the mid-1800s, hard cider was the primary alcoholic drink of the people. Hard cider was prominent throughout this entire period and nothing compared in scope or availability. It was one of the few aspects of American culture that all the colonies shared. Settlement along the frontier often included a legal requirement whereby an orchard of mature apple trees bearing fruit within three years of settlement were required before a land title was officially granted. For example, The Ohio Company required settlers to plant not less than fifty apple trees and twenty peach trees within three years. These plantings would guarantee land titles. In 1767, the average New England family was consuming seven barrels of hard cider annually, which equates to about 35-gallons per person. Around the mid-1800s, newly arrived immigrants from Germany and elsewhere increased beer's popularity, and the temperance movement and continued westward expansion caused farmers to abandon their cider orchards.

Surprisingly, most supporters of the movement were heavy drinkers themselves, according to a study done by an insider. Attitudes towards alcohol began to change in the late 18th century. One of the reasons for this was the need for sober laborers to operate heavy machinery developed in the Industrial Revolution. Anthony Benezet suggested abstinence from alcohol in 1775. As early as the 1790s, physician Benjamin Rush researched the danger that drinking alcohol could lead to disease that leads to a lack of self-control, and he cited abstinence as the only treatment option. Rush saw benefits in fermented drinks, but condemned the use of distilled spirits. As well as addiction, Rush noticed the correlation that drunkenness had with disease, death, suicide, and crime. According to "Pompili, Maurizio et al", there is increasing evidence that, aside from the volume of alcohol consumed, the pattern of the drinking is relevant for health outcomes. Overall, there is a causal relationship between alcohol consumption and more than 60 types of diseases and injuries. Alcohol is estimated to cause about 20–30% of cases of esophageal cancer, liver cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, homicide, epilepsy and motor vehicle accidents. After the American Revolution, Rush called upon ministers of various churches to act in preaching the messages of temperance. However, abstinence messages were largely ignored by Americans until the 1820s.

History

Temperance is one of the cardinal virtues listed in Aristotle's tractate the Nicomachean Ethics.

Origins (pre-1820)

During the 18th century, Native American cultures and societies were severely affected by alcohol, which was often given in trade for furs, leading to poverty and social disintegration. As early as 1737, Native American temperance activists began to campaign against alcohol and for legislation to restrict the sale and distribution of alcoholic drinks in indigenous communities. During the colonial era, leaders such as Peter Chartier, King Hagler and Little Turtle resisted the use of rum and brandy as trade items, in an effort to protect Native Americans from cultural changes they viewed as destructive.

In the 18th century, there was a "gin craze" in Great Britain. The middle classes became increasingly critical of the widespread drunkenness among the lower classes. Motivated by the middle-class desire for order, and amplified by the population growth in the cities, the drinking of gin became the subject of critical national debate. In 1743, John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Churches, proclaimed "that buying, selling, and drinking of liquor, unless absolutely necessary, were evils to be avoided".

In the early 19th-century United States, alcohol was still regarded as a necessary part of the American diet for both practical and social reasons. On one hand, water supplies were often polluted, milk was not always available, and coffee and tea were expensive. On the other hand, social constructs of the time made it impolite for people (particularly men) to refuse alcohol. Drunkenness was not a problem, because people would only drink small amounts of alcohol throughout the day; at the turn of the 19th century, however, overindulgence and subsequent intoxication became problems that often led to the disintegration of the family. Early temperance societies, often associated with churches, were located in upstate New York and New England, but only lasted a few years. These early temperance societies called for moderate drinking (hence the name "temperance"), but had little influence outside of their geographical areas.

In 1810, Calvinist ministers met in a seminary in Massachusetts to write articles about abstinence from alcohol to use in preaching to their congregations. The Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance (MSSI) was formed in 1813. The organization only accepted men of high social standing and encouraged moderation in alcohol consumption. Its peak of influence was in 1818, and it ended in 1820, having made no significant mark on the future of the temperance movement. Other small temperance societies appeared in the 1810s, but had little impact outside their immediate regions and they disbanded soon after. Their methods had little effect in implementing temperance, and drinking actually increased until after 1830; however, their methods of public abstinence pledges and meetings, as well as handing out pamphlets, were implemented by more lasting temperance societies such as the American Temperance Society.

The first temperance society in Pennsylvania, of which a record has been found was that of "Darby Association for Discouraging the Unnecessary Use of Spirituous Liquors" organized in Delaware County in 1819, at the Darby Friends Meetinghouse. (Pg 20 Temperance Movement Prior to the Civil War, Asa Earl Martin; The PA Magazine of History & Biography, 1925 Vol 49 #3)

Promoting moderation (1820s–1830s)

The temperance movement in the United States began at a national level in the 1820s, having been popularized by evangelical temperance reformers and among the middle classes. There was a concentration on advice against hard spirits rather than on abstinence from all alcohol, and on moral reform rather than legal measures against alcohol. An earlier temperance movement had begun during the American Revolution in Connecticut, Virginia and New York state, with farmers forming associations to ban whiskey distilling. The movement spread to eight states, advocating temperance rather than abstinence and taking positions on religious issues such as observance of the Sabbath.

After the American Revolution there was a new emphasis on good citizenship for the new republic. With the Evangelical Protestant religious revival of the 1820s and 1830s, called the Second Great Awakening, social movements began aiming for a perfect society. This included abolitionism and temperance. The Awakening brought with it an optimism about moral reform, achieved through volunteer organizations. Although the temperance movement was nonsectarian in principle, the movement consisted mostly of church-goers.

The temperance movement promoted temperance and emphasized the moral, economical and medical effects of overindulgence. Connecticut-born minister Lyman Beecher published a book in 1826 called Six Sermons on...Intemperance. Beecher described inebriation as a "national sin" and suggested legislation to prohibit the sales of alcohol. He believed that it was only possible for drinkers to reform in the early stages of addiction, because anyone in advanced stages of addiction, according to Beecher, had damaged their morality and could not be saved. Early temperance reformers often viewed drunkards as warnings rather than as victims of a disease, leaving the state to take care of them and their conduct. In the same year, the American Temperance Society (ATS) was formed in Boston, Massachusetts, within 12 years claiming more than 8,000 local groups and over 1,250,000 members. Presbyterian preacher Charles Grandison Finney taught abstinence from ardent spirits. In the Rochester, New York revival of 1831, individuals were required to sign a temperance pledge in order to receive salvation. Finney believed and taught that the body represented the "temple of God" and anything that would harm the "temple", including alcohol, must be avoided. By 1833, several thousand groups similar to the ATS had been formed in most states. In some of the large communities, temperance almanacs were released which gave information about planting and harvesting as well as current information about the temperance issues.

Temperance societies were being organized in England about the same time, many inspired by a Belfast professor of theology, and Presbyterian Church of Ireland minister John Edgar, who poured his stock of whiskey out of his window in 1829. He mainly concentrated his fire on the elimination of spirits rather than wine and beer. On August 14, 1829 he wrote a letter in the Belfast Telegraph publicizing his views on temperance. He also formed the Ulster Temperance Movement with other Presbyterian clergy, initially enduring ridicule from members of his community.

The 1830s saw a tremendous growth in temperance groups, not just in England and the United States, but also in British colonies, especially New Zealand and Australia. The Pequot writer and minister William Apess (1798–1839) established the first formal Native American temperance society among the Maspee Indians on 11 October 1833.

Out of the religious revival and reform appeared the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Seventh-day Adventism, new Christian denominations that established criteria for healthy living as a part of their religious teachings, namely temperance.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Word of Wisdom is a health code followed by the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and other Latter Day Saint denominations which advises how to maintain good health: what one should do and what one should abstain from. One of the most prominent items in the Word of Wisdom is the complete abstinence from alcohol. When the Word of Wisdom was written, the Latter Day Saints were residing in Kirtland, Ohio and the Kirtland Temperance Society was organized on October 6, 1830, with 239 members. According to some scholars, the Word of Wisdom was influenced by the temperance movement. In June 1830, the Millenial Harbinger quoted from a book "The Simplicity of Health" which strongly condemned the use of alcohol and tobacco, and the untempered consumption of meat, similar to the provisions in the Word of Wisdom revealed three years later. This gave publicity to the movement and Temperance Societies began to form. On February 1, 1833, a few weeks before the Word of Wisdom was published, all distilleries in the Kirtland area were shut down. During the early history of the Word of Wisdom, temperance and other items in the health code were seen more as wise recommendations than as commandments.

Although he advocated temperance, Joseph Smith did not preach complete abstinence from alcohol. According to Paul H. Peterson and Ronald W. Walker, Joseph Smith did not enforce abstinence from alcohol because he believed it would threaten individual choice and agency, and that forcing the Latter Day Saints to comply would cause division in the Church. In Harry M. Beardsley's book Joseph Smith and his Mormon Empire, Beardsley argues that some Mormon historians attempted to portray Joseph Smith as a teetotaler, but according to the testimonies of his contemporaries, Joseph Smith often drank alcohol in his own home or the homes of his friends in Kirtland. In Nauvoo, Illinois Smith was far less discreet with his drinking habits. However, at the end of the 19th century, second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Brigham Young said that the Saints could no longer justify disobeying the Word of Wisdom because of the way that it was originally presented. In 1921, Heber J. Grant, then president of the LDS church, officially called on the Latter-day Saints to strictly adhere to the Word of Wisdom, including complete abstinence from alcohol.

Millerites and Seventh-day Adventists

The founder of the Millerites, William Miller, claimed that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ would be in 1843, and that anyone who drank alcohol would be unprepared for the Second Coming. After the Great Disappointment in 1843, the Seventh-day Adventist denomination adopted health reforms inspired by influential church pioneers Ellen G. White and her husband, a preacher, James Springer White, who did not use alcohol or tobacco. Ellen preached healthful living to her followers, without specifying abstinence from alcohol, as most of her followers were temperance followers, and abstinence would have been implied.

Teetotalism (1830s)

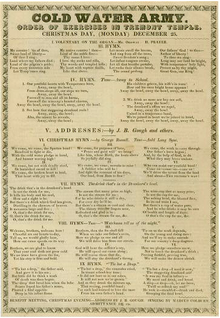

As a response to rising social problems in urbanized areas, a stricter form of temperance emerged called teetotalism, which promoted the complete abstinence from alcoholic beverages, this time including wine and beer, not just ardent spirits. The name "teetotaler" came from the capital "T"s that were written next to the names of people who pledged complete abstinence from alcohol. People were instructed to only drink pure water and the teetotalists were known as the "pure-water army". In the US, the American Temperance Union advocated total abstinence from distilled and fermented liquors. By 1835, they had gained 1.5 million members. This created conflict between the teetotalists and the more moderate members of the ATS. Even though there were temperance societies in the South, as the movement became more closely tied with the abolitionist movement, people in the South created their own teetotal societies. Considering drinking to be an important part of their cultures, German and Irish immigrants resisted the movement. In the UK, teetotalism originated in Preston, in 1833. The Catholic temperance movement started in 1838 when the Irish priest Theobald Mathew established the Teetotal Abstinence Society in 1838. In 1838, the mass working class movement for universal suffrage for men, Chartism, included a current called "temperance chartism". Faced with the refusal of the Parliament of the time to give the right to vote to working people, the temperance chartists saw the campaign against alcohol as a way of proving to the elites that working-class people were responsible enough to be granted the vote. In short, the 1830s was mostly characterized by moral persuasion of workers.

Growing radicalism and influence (1840s–1850s)

The Washingtonian movement

In 1840, a group of artisans in Baltimore, Maryland created their own temperance society that could appeal to hard-drinking men like themselves. Calling themselves the Washingtonians, they pledged complete abstinence, attempting to persuade others through their own experience with alcohol rather than relying on preaching and religious lectures. They argued that sympathy was an overlooked method for helping people with alcohol addictions, citing coercion as an ineffective method. For that reason, they did not support prohibitive legislation of alcohol. They were suspicious of the divisiveness of denominational religion and did not use religion in their discussions, emphasizing personal abstinence. They never set up national organizations, believing that concentration of power and distance from citizens causes corruption. Meetings were public and they encouraged equal participation, appealing to both men and women and northerners and southerners. Unlike early temperance reformers, the Washingtonians did not believe that intemperance destroyed a drinker's morality. They worked on the platform that abstinence communities could be created through sympathizing with drunkards rather than ostracizing them through the belief that they are sinners or diseased.

On February 22, 1842 in Springfield, Illinois, while a member of the Illinois Legislature, Abraham Lincoln gave an address to the Springfield Washington Temperance Society on the 110th anniversary of the birth of George Washington. In the speech, Lincoln criticized early methods of the temperance movement as overly forceful and advocated reason as the solution to the problem of intemperance, praising the current temperance movement methods of the Washingtonian movement.

By 1845, the Washingtonian movement was no longer as prominent for three reasons. Firstly, the evangelist reformers attacked them for refusing to admit alcoholism was a sin. Secondly, the movement was criticized as unsuccessful due to the number of men who would go back to drinking. Finally, the movement was internally divided by differing views on prohibition legislation. Temperance fraternal societies such as the Sons of Temperance and the Good Samaritans took the place of the Washingtonian movement with largely similar views relating to helping alcoholics by way of sympathy and philanthropy. They, however, differed from the Washingtonians through their closed rather than public meetings, fines, and membership qualifications, believing their methods would be more effective in curbing men's alcohol addictions. After the 1850s, the temperance movement was characterized more by prevention by means of prohibitions laws, than remedial efforts to facilitate the recovery of alcoholics.

Gospel temperance

By the mid-1850s, the United States was divided from differing views of slavery and prohibition laws and economic depression. This influenced the Third Great Awakening in the United States. The prayer meeting largely characterized this religious revival. Prayer meetings were devotional meetings run by laypeople rather than clergy and consisted of prayer and testimony by attendees. The meetings were held frequently and pledges of temperance were confessed. Prayer meetings and pledges characterized the post-Civil war "gospel" temperance movement. This movement was similar to early temperance movements in that drunkenness was seen as a sin; however, public testimony was used to convert others and convince them to sign the pledge. New and revitalized organizations emerged including the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and the early Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The movement relied on the reformed individuals using local evangelical resources to create institutions to reform drunk men. Reformed men in Massachusetts and Maine formed "ribbon" clubs to support men who were interested in stopping drinking. Ribbon reformers traveled throughout the Midwest forming clubs and sharing their experiences with others. Gospel rescue missions or inebriate homes were created that allowed homeless drunkards a safe place to reform and learn to practice total abstinence while receiving food and shelter. These movements emphasized sympathy over coercion, yet unlike the Washingtonian movements, emphasized helplessness as well with relief from their addictions as a result from seeking the grace of God.

As an expression of moralism, the membership of the temperance movement overlapped with that of the abolitionist movement and women's suffrage movement.

During the Victorian period, the temperance movement became more political, advocating the legal prohibition of all alcohol, rather than only calling for moderation. Proponents of temperance, teetotalism and prohibition came to be known as the "drys".

There was still a focus on the working class, but also their children. The Band of Hope was founded in 1847 in Leeds, UK, by the Reverend Jabez Tunnicliff. It aimed to save working class children from the drinking parents by teaching them the importance and principles of sobriety and teetotalism. In 1855, a national organisation was formed amidst an explosion of Band of Hope work. Meetings were held in churches throughout the UK and included Christian teaching. The group campaigned politically for the curtailment of the influence of pubs and brewers. The organization became quite radical, organizing rallies, demonstrations and marches to influence as many people as possible to sign the pledge of allegiance to the society and to resolve to abstain "from all liquors of an intoxicating quality, whether ale, porter, wine or spirits, except as medicine."

In this period there was local success at restricting or banning the sale of alcohol in many parts of the United States. In 1838, Massachusetts banned certain sales of spirits. The law was repealed two years later, but it set a precedent. In 1845, Michigan allowed its municipalities to decide whether they were going to prohibit. In 1851, a law was passed in Maine which was a full-fledged prohibition, and this was followed by bans in several other states in the next two decades.

The movement became more effective, with alcohol consumption in the US being decreased by half between 1830 and 1840. During this time, prohibition laws came into effect in twelve US states, such as Maine. Maine Law was passed in 1851 by the efforts of Neal Dow. Organized opposition caused five of these states to eliminate or weaken the laws.

Transition to a mass movement (1860s–1900s)

The Temperance movement was a significant mass movement at this time and it encouraged a general abstinence from the consumption of alcohol. A general movement to build alternatives to replace the functions of public bars existed, so the Independent Order of Rechabites was formed in England, with a branch later opening in the US as a friendly society that did not hold meetings in public bars. There was also a movement to introduce temperance fountains across the United States—to provide people with reliably safe drinking water rather than saloon alcohol.

In the United States, the National Prohibition Party which was led by John Russell gradually became more popular, gaining more votes, as they felt that the existing Democrat and Republican parties did not do enough for the temperance cause. The party was associated with the Independent Order of Good Templars, which entertained a universalist orientation, being more open to blacks and repentant alcoholics than most other organizations.

Reflecting the teaching on alcohol of their founder John Wesley, Methodist Churches were aligned with the temperance movement. Methodists believed that despite the supposed economic benefits of liquor traffic such as job creation and taxes, the harm that it caused society through its contribution to murder, gambling, prostitution, crime, and political corruption outweighed its economic benefits. In Great Britain, both Wesleyan Methodists and Primitive Methodists championed the cause of temperance; the Methodist Board of Temperance, Prohibition, and Public Morals was later established in the United States to further the movement. In 1864, the Salvation Army, another denomination in the Wesleyan-Arminian tradition, was founded in London with a heavy emphasis on abstinence from alcohol and ministering to the working class, which led publicans to fund a Skeleton Army in order to disrupt their meetings. The Salvation Army quickly spread internationally, maintaining an emphasis on abstinence.any of the most important prohibitionist groups, such as the avowedly prohibitionist United Kingdom Alliance (1853) and the US-based (but international) Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU; 1873), began in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the latter of which was one of the largest women's societies in the world at that time. But the largest and most radical international temperance organization was the Good Templars. In 1862, the Soldiers Total Abstinence Association was founded in British India by Joseph Gelson Gregson, a Baptist missionary. In 1898, the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association was formed by James Cullen, an Irish Catholic, which spread to other English-speaking Catholic communities.

In 1870, a group of physicians founded the American Association of the Cure of Inebrity (AACI) in order to treat alcohol addiction. The two goals of this organization were to convince skeptical members of the medical community of the existence and seriousness of the disease of alcoholism and prove the efficacy of asylum treatments for alcoholics. They argued for more genetic causes of alcohol addictions. Treatments often included restraining patients while they reformed, both physically and morally.

During the same period, there was significant pushback against the growing temperance movement, particularly in urban areas with significant European immigrant communities. Chicago political bosses A.C. Hesing and Hermann Raster forced the Republican Party to adopt an anti-temperance platform at the 1872 Republican National Convention with the threat of taking the German and European vote away from the party. The following year, Hesing formed the People's Party, a breakaway pro-liquor faction of the Republican Party, and elected Harvey Doolittle Colvin as Mayor of Chicago by a wide margin.

The Anti-Saloon League was an organization that began in Ohio in 1893. Reacting to urban growth, it was driven by evangelical Protestantism. Furthermore, the League was strongly supported by the WCTU: in some US states alcoholism had become epidemic and rates of domestic violence were also high. At that time, Americans drank about three times as much alcohol as they drank in the 2010s. The League simultaneously campaigned for suffrage and temperance, with its leader Susan B. Anthony stating that "The only hope of the Anti-Saloon League's success lies in putting the ballot into the hands of women", i.e. it was expected that the first act that women were to take upon themselves after having obtained the right to vote, was to vote for an alcohol ban.

The actions of the temperance movement included organizing sobriety lectures and setting up reform clubs for men and children. Some proponents also opened special temperance hotels and lunch wagons, and they also lobbied for banning liquor during prominent events. The Scientific Temperance Instruction Movement published textbooks, promoted alcohol education and held many lectures. Political action included lobbying local legislators and creating petition campaigns.

This new trend in the history of the temperance movement would be the last but it would also prove to be the most effective. Scholars have estimated that by 1900, one in ten Americans had signed a pledge to abstain from drinking, as the temperance movement became the most well-organized lobby group of the time. International conferences were held, in which temperance advocacy methods and policies were discussed. By the turn of the century, temperance societies became commonplace in the US.

During that time, there was also a growth in the number of non-religious temperance groups which were linked to left-wing movements, such as the Scottish Prohibition Party. Founded in 1901, it went on to defeat Winston Churchill in Dundee in the 1922 general election.

Legislative successes and failures (1910s)

A favorite goal of the British Temperance movement was sharply to reduce heavy drinking by closing as many pubs as possible. Advocates were Protestant nonconformists who played a major role in the Liberal Party. The Liberal Party adopted temperance platforms focused on local option. In 1908, Prime Minister H.H. Asquith—although a heavy drinker himself—took the lead by proposing to close about a third of the 100,000 pubs in England and Wales, with the owners compensated through a new tax on surviving pubs. The brewers controlled the pubs and organized a stiff resistance, supported by the Conservatives, who repeatedly defeated the proposal in the House of Lords. However, the People's Tax of 1910 included a stiff tax on pubs.

The movement gained further traction during the First World War, with President Wilson issuing sharp restrictions on the sale of alcohol in many combatant countries. This was done to preserve grain for food production. During this time, prohibitionists used anti-German sentiment related to the war to rally against alcohol sales, since many brewers were of German-American descent.

L'Alarme: société française d'action contre l'alcoolisme was a movement in France, inaugurated in 1914, under the auspices of the Ligue National contre l'Alcoolisme (French National League Against Alcoholism), to bring public sentiment for increased restrictions upon the liquor traffic to bear upon the election of candidates for the Chamber of Deputies. So late as 1919, L'Alarme not only did not oppose fermented liquors, but considered wine and wine-producers among the most powerful forces against ardent spirits, to which the alcoholism opposed by L'Alarme was considered to be due.

According to alcohol researcher Johan Edman, the first country to issue an alcohol prohibition was Russia, as part of war mobilization policies. This followed after Russia had made significant losses in the war against the sober Japanese in 1905. In the UK, the Liberal government passed the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 when pub hours were licensed, beer was watered down and was subject to a penny a pint extra tax, and in 1916 a State Management Scheme meant that breweries and pubs in certain areas of Britain were nationalized, especially in places where armaments were made.

In 1913, the ASL began its efforts for national prohibition. Wayne Wheeler, a member of the Anti-Saloon League was integral in the prohibition movement in the United States. He used hard political persuasion called "Wheelerism" in the 1920s of legislative bodies. Rather than ask directly for a vote, which Wheeler viewed as weak, Wheeler would cover the desks of legislators in telegrams. He was also accomplished in rallying supporters; the Cincinnati Enquirer called Wheeler "the strongest political force of his day". His efforts specifically influenced the passing of the eighteenth-amendment. And in 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment was successfully passed in the United States, introducing prohibition of the manufacture, sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages. The amendment, also called "the noble experiment", was preceded by the National Prohibition Act, which stipulated how the federal government should enforce the amendment.

National prohibition was proposed several times in New Zealand as well, and nearly successful. On a similar note, Australian states and New Zealand introduced restrictive early closing times for bars during and immediately after the First World War. In Canada, in 1916 the Ontario Temperance Act was passed, prohibiting the sales of alcoholic beverages with more than 2.5% alcohol. In the 1920s imports of alcohol were cut off by provincial referendums.

Norway introduced partial prohibition in 1917, which became full prohibition through a referendum in 1919, although this was overturned in 1926. Similarly, Finland introduced prohibition in 1919, but repealed it in 1932 after an upsurge in violent crime associated with criminal opportunism and the illegal liquor trade. Iceland introduced prohibition in 1915, but liberalized consumption of spirits in 1933, although beer was still illegal until 1989. In the 1910s, half of the countries in the world had introduced some form of alcohol control in their laws or policies.

Association with independence movements (1920s–1960s)

The temperance movement started to wane in the 1930s, with prohibition being criticised as creating unhealthy drinking habits, encouraging criminals and discouraging economic activity. Prohibition would not last long: the legislative tide largely moved away from prohibition when the Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution was ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing nationwide prohibition. The gradual relaxation of licensing laws went on throughout the 20th century, with Mississippi being the last state to end prohibition in 1966. In Australia, early hotel closing times were reverted in the 1950s and 1960s.

Initially, prohibition had some positive effects in some states, with Ford reporting that absenteeism in his companies had decreased by half. Alcohol consumption decreased dramatically. Also, statistical analysis has shown that the temperance movement during this time had a positive, though moderate, effect on later adult educational outcomes through providing a healthy pre-natal environment. However, prohibition had negative effects on the US economy, with thousands of jobs being lost, the catering and entertainment industries losing huge profits. The US and other countries with prohibition saw their tax revenues decrease dramatically, with some estimating this at a loss of 11 billion dollars for the US. Furthermore, enforcement of the alcohol ban was an expensive undertaking for the government. Because the Eighteenth Amendment did not prohibit consumption, but only manufacture, distribution and sale, illegal consumption became commonplace. Illegal production of alcohol rose, and a thousand people per year died of alcohol that was illegally produced with little quality control. Bootlegging was a profitable activity, and crime increased rather than decreased as expected and advocated by proponents.

In the United States, the temperance movement itself was in decline: fundamentalist and nativist groups had become dominant in the movement, which led moderate members to leave the movement.

During this time, in former colonies (such as Gujarat in India, Sri Lanka and Egypt), the temperance movement was associated with anti-colonialism or religious revival. As such, the temperance movement in India became closely tied with the Indian independence movement as Mahatma Gandhi viewed alcohol as being a foreign importation. He viewed foreign rule as the reason that national prohibition was not yet established at his time.

1960s–present

The temperance movement still exists in many parts of the world, although it is generally less politically influential than it was in the early 20th century. Its efforts today include disseminating research regarding alcohol and health, in addition to its effects on society and the family unit.

The addition of warning labels on alcoholic beverages is supported by organizations of the temperance movement, such as the WCTU.

Prominent temperance organizations active today include the World Woman's Christian Temperance Union, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, Alcohol Justice, International Blue Cross, Independent Order of Rechabites, and International Organisation of Good Templars.

The Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection, a Methodist denomination in the conservative holiness movement, as well as the Salvation Army, for example, are Christian Churches that continue to require that their members refrain from drinking alcohol as well as smoking, taking illegal drugs, and gambling.

In youth culture in the 1990s, temperance was an important part of the straight edge scene, which also stressed abstinence from other drugs.

Fitzpatrick's Herbal Health in Lancashire, England, is thought to be the oldest temperance bars and other such establishments have become popular in recent times.

In various parts of the world, voters continue to advocate for alcohol prohibition. For example, in 2016, many women in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu blamed alcohol for societal ills, such as domestic violence, and thus took to the polls to elect a pro-prohibition leader. Their effort succeeded and when Jayaram Jayalalithaa was voted in, she shut down five hundred liquor shops on her first day in office. In 2017, women agitated for temperance and the prohibition of alcohol in the state of Bihar; they campaigned for the election of Nitish Kumar, who upon the request of women, pledged that he would prohibit alcohol. Since signing prohibition legislation, "Murders and gang robberies are down almost 20 percent from a year earlier, and riots by 13 percent. Fatal traffic accidents fell by 10 percent."

Beliefs, principles and culture

Temperance proponents saw the alcohol problem as the most crucial problem of Western civilization. Alcoholism was seen to cause secondary poverty, and all types of social problems: alcohol was the enemy of everything good that modernity and science had to offer. They believed that abstinence would help decrease crime, make families stronger, and improve society as a whole. Although the temperance movement was non-denominational in principle, the movement consisted mostly of church-goers. Temperance advocates tended to use scientific arguments to back up their views, although at the core the temperance philosophy was moral-religious in nature. The alcohol problem was connected with a sense of purpose and modernity of the western nation, and was largely international in nature, in keeping with the international optimism typical for the period preceding the First World War.

Historical analysis of conference documents helps create an image of what the temperance movement stood for. The movement believed that alcohol use disorder was a threat to scientific progress, as it was believed citizens had to be strong and sober to be ready for the modern age. Progressive themes and causes such as abolition, natural self-determination, worker's rights, and the importance of women in rearing children to be good citizens were key themes of this citizenship ideology. The movement put itself at service of the state, but was also critical of it. In that sense, it was a radical movement with liberal and socialist aspects, although in some parts of the world, notably the US, allied with conservatism. Alcohol was often associated with oppression: not only oppression in the West, but also in colonies. Temperance advocates saw alcohol as a product that "... enables a few to become rich while it impoverishes the very many". Temperance advocates worked closely with the labor movement, as well as the women suffrage movement, partly because there was mutual support and benefit, and the causes were seen as connected.

Prevention, treatment and restriction

Temperance proponents used a variety of means to prevent and treat alcohol use disorder and restrict its consumption. At the end of the nineteenth century, medically-oriented treatment of alcohol use disorder became more common. In a trend that was preceded by Rush's writings, alcoholism came to be seen as an illness which could be medically treated. Scientists who were temperance proponents attempted to find the underlying causes of alcohol use disorder. At the same time, criticism rose toward use of alcohol in medical care. The notion of alcohol use disorder as a disease would only become widely accepted much later, however, until after the Second World War.

Nevertheless, restriction of consumption was most emphasized in the movement, though ideas on how to accomplish this were varied and conflicting. Apart from the prohibition by law, there were also ideas to establish state monopoly on all alcohol sales, or through law reform remove profit from the alcohol industry.

During the 1900s decade, the ideal of strong citizens was further developed into the hygienism ideology. Through the influence of scientific theories on heredity, temperance proponents came to believe that alcohol problems were not just a personal concern, but would cause later generations of people to "degenerate" as well. Public hygiene and improving the population through personal lifestyle were therefore promoted. A variety of temperance halls, temperance bars and coffee palaces were established as replacements for saloons. Numerous periodicals devoted to temperance were published and temperance theatre, which had started in the 1820s, became an important part of the American cultural landscape at this time. The temperance movement generated its own popular culture. Popular songwriters such as Susan McFarland Parkhurst, George Frederick Root, Henry Clay Work and Stephen C. Foster composed a number of these songs. At temperance inns puppet plays, minstrel acts, parades and other shows were held.

Role of women

Much of the temperance movement was based on organized religion, which saw women as responsible for edifying their children to be abstaining citizens. Nevertheless, temperance was tied in with both religious renewal and progressive politics, particularly female suffrage. Furthermore, temperance activists were able to promote suffrage more effectively than suffrage activists were, because of their wide-ranging experiences as activists, and because they argued for a concrete desire for safety at home, rather than for an abstract desire for justice as suffragists did.

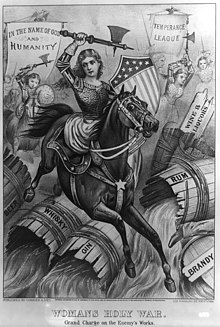

By 1831, there were over 24 women's organizations which were dedicated to the temperance movement. Women were specifically drawn to the temperance movement, because it represented a fight to end a practice that greatly affected women's quality of life. Temperance was seen as a feminine, religious and moral duty, and when it was achieved, it was also seen as a way to gain familial and domestic security as well as salvation in a religious sense. Indeed, scholar Ruth Bordin stated that the temperance movement was "the foremost example of American feminism." Prominent women such as Amelia Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony were active in temperance and abolitionist movements in the 1840s.

A myriad of factors contributed to women's interest in the temperance movement. One of the initial contributions was the frequency in which women were the victims of those who had an alcohol use disorder. At a Chicago meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, Susan B. Anthony stated that women suffer the most from drunkenness. The inability of women to control wages, vote, or own property added to their vulnerability. Another contribution was related to the role of women in the home in the nineteenth century which was largely to preside over the spiritual and physical needs of their homes and families. Because of this, women believed that it was their duty to protect their families from the danger of alcohol and convert their family members to the ideas of abstinence. This newfound calling to temperance, however, did not change the widely held viewpoint that women were only responsible for matters which pertained to their homes. Consequently, women had what Ruth Bordin referred to as the "maternal struggle" which women felt was the internal contradiction that came with their newly-discovered power to make change, while still believing in their nurturing and domestic roles without yet understanding how to use their newly-acquired power. June Sochen called women who joined movements such as women's temperance organizations "pragmatic feminists", because they took action to solve their grievances, but were not interested in altering traditional sex roles. The missionary organizations of many Protestant denominations gave women an avenue to work from; several all-female missionary societies already existed and it was easy for them to transform themselves into women's temperance organizations.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the number of women who were in the middle and upper classes was large enough to support women's participation in the temperance movement. Higher class women did not need to work because they could rely on their husbands' ability to support their families and they consequently had more leisure time to engage in organizations and associations that were affiliated with the temperance movement. The influx of Irish immigrants filled the servant jobs that freed African-Americans left after the American Civil War, leaving upper and middle-class women with even more time to participate in the community while domestic jobs were being filled. Moreover, the birth rate had fallen, leaving women with an average of four children in 1880 as compared to seven children at the beginning of the nineteenth-century. The gathering of people in urban areas and the extra leisure time for women contributed to the mass female temperance movement.

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) grew out of a spontaneous crusade against saloons and liquor stores that began in Ohio and spread throughout the Midwestern United States during the winter of 1873–1874. The crusade consisted of over 32,000 women who stormed into saloons and liquor stores in order to disrupt business and stop the sales of alcohol. The WCTU was officially organized in late November 1874 in Cleveland, Ohio. Frances Willard, the organization's second president, helped grow the organization into the largest women's religious organization in the 19th century. Willard was interested in suffrage and women's rights as well as temperance, believing that temperance could improve the quality of life on both the family and community level. The WCTU trained women in skills such as public speaking, leadership, and political thinking, using temperance as a springboard to achieve a higher quality of life for women on many levels. In 1881, the WCTU began lobbying for the mandation of instruction in temperance in public schools. In 1901, schools were required to instruct students on temperance ideas, but they were accused of perpetuating misinformation, fear mongering, and racist stereotypes. Carrie Nation was one of the most extreme temperance movement workers and she was arrested 30 times for destroying property at bars, saloons, and even pharmacies, believing that even alcohol which was used for medicine was unjustified. At the approach of the 20th century, the temperance movement became more interested in legislative reform as pressure from the Anti-Saloon League increased. Women, who had not yet achieved suffrage, became less central to the movement in the early 1900s.

Other causes

Prohibition agendas also became popular among factory owners, who strove for more efficiency during a period of increased industrialization. For this reason, industrial leaders such as Henry Ford and S.S. Kresge supported Prohibition. The cause of the sober factory worker was related to the cause of women temperance leaders: concerned mothers protested against the enslavement of factory workers, as well as the temptation which saloons offered to these workers. Efficiency was also an important argument for the government because it wanted its soldiers to be sober.

At the end of the nineteenth century, temperance movement opponents started to criticize the slave trade in Africa. This came during the last period of rapid colonial expansion. Slavery and the alcohol trade in colonies were seen as two closely related problems, and they were frequently called "the twin oppressors of the people". Again, this subject tied in with the ideas of civilization and effectiveness: temperance advocates raised the issue that the "natives" could not be properly "civilized" and put to work, if they were provided with the vice of alcohol.