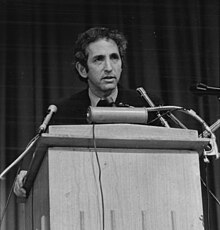

Daniel Ellsberg | |

|---|---|

Ellsberg in 1972 | |

| Born | April 7, 1931 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 16, 2023 (aged 92) Kensington, California, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Employer | RAND Corporation |

| Known for | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | |

| Awards | Right Livelihood Award |

| Military career | |

| Service/ | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1954–1957 |

| Rank | First lieutenant |

| Unit | 2nd Marine Division |

| Website | www |

Daniel Ellsberg (April 7, 1931 – June 16, 2023) was an American political activist, economist, and United States military analyst. While employed by the RAND Corporation, he precipitated a national political controversy in 1971 when he released the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Pentagon study of U.S. government decision-making in relation to the Vietnam War, to The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other newspapers.

In January 1973, Ellsberg was charged under the Espionage Act of 1917 along with other charges of theft and conspiracy, carrying a maximum sentence of 115 years. Because of governmental misconduct and illegal evidence-gathering (committed by the same people who would later be involved in the Watergate scandal), and his defense by Leonard Boudin and Harvard Law School professor Charles Nesson, Judge William Matthew Byrne Jr. dismissed all charges against Ellsberg in May 1973.

Ellsberg was awarded the Right Livelihood Award in 2006. He was also known for having formulated an important example in decision theory, the Ellsberg paradox; for his extensive studies on nuclear weapons and nuclear policy; and for voicing support for WikiLeaks, Chelsea Manning, and Edward Snowden. Ellsberg was awarded the 2018 Olof Palme Prize for his "profound humanism and exceptional moral courage".

Early life and career

Ellsberg was born in Chicago, Illinois, on April 7, 1931, the son of Harry and Adele (Charsky) Ellsberg. His parents were Ashkenazi Jews who had converted to Christian Science, and he was raised as a Christian Scientist. In 2008, Ellsberg told a journalist that his parents considered the family Jewish, "but not in religion."

Ellsberg grew up in Detroit and attended the Cranbrook School in nearby Bloomfield Hills. His mother wanted him to be a concert pianist, but he stopped playing in July 1948, two years after both his mother and sister were killed when his father fell asleep at the wheel and crashed the family car into a bridge abutment.

Ellsberg entered Harvard College on a scholarship, graduating summa cum laude with an A.B. in economics in 1952. He studied at King's College, Cambridge, for a year through funding from the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, initially for a diploma in economics and then changed his credits toward a Ph.D. in the subject, before returning to Harvard. In 1954, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and earned a commission. He served as a platoon leader and company commander in the 2nd Marine Division, and was discharged in 1957 as a first lieutenant. Ellsberg returned to Harvard as a Junior Fellow in the Society of Fellows for two years.

RAND Corporation and PhD

Ellsberg began working as a strategic analyst at the RAND Corporation for the summer of 1958 and then permanently in 1959. He concentrated on nuclear strategy, working with leading strategists such as Herman Kahn and challenging the existing plans of the United States National Security Council and Strategic Air Command.

Ellsberg completed a PhD in economics from Harvard in 1962. His dissertation on decision theory was based on a set of thought experiments that showed that decisions under conditions of uncertainty or ambiguity generally may not be consistent with well-defined subjective probabilities. Now known as the Ellsberg paradox, it formed the basis of a large literature that has developed since the 1980s, including approaches such as Choquet expected utility and info-gap decision theory.

Ellsberg worked in the Pentagon from August 1964 under Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara as special assistant to Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs John McNaughton. He then went to South Vietnam for two years, working for General Edward Lansdale as a member of the State Department.

On his return from South Vietnam, Ellsberg resumed working at RAND. In 1967, he contributed with 33 other analysts to a top-secret 47-volume study of classified documents on the conduct of the Vietnam War, commissioned by Defense Secretary McNamara and supervised by Leslie H. Gelb and Morton Halperin. These 7,000 pages of documents, completed in late 1968 and presented to McNamara and Clark Clifford early in the following year, later became known collectively as the "Pentagon Papers".

Disaffection with Vietnam War

By 1969, Ellsberg began attending anti-war events while still remaining in his position at RAND. In April 1968, Ellsberg attended a Princeton University conference on "Revolution in a Changing World", where he met Gandhian peace activist Janaki Natarajan Tschannerl from India, who had a profound influence on him, and Eqbal Ahmed, a Pakistani fellow at the Adlai Stevenson Institute later to be indicted with Rev. Philip Berrigan for anti-war activism. Ellsberg particularly recalled Tschannerl saying "In my world, there are no enemies", and that "she gave me a vision, as a Gandhian, of a different way of living and resistance, of exercising power nonviolently."

Ellsberg experienced an epiphany attending a War Resisters International conference at Haverford College in August 1969, listening to a talk given by Randy Kehler, a draft resister, who said he was "very excited" that he would soon be able to join his friends in prison.

Decades later, Ellsberg described his reaction to hearing Kehler speak:

And he said this very calmly. I hadn't known that he was about to be sentenced for draft resistance. It hit me as a total surprise and shock, because I heard his words in the midst of actually feeling proud of my country listening to him. And then I heard he was going to prison. It wasn't what he said exactly that changed my worldview. It was the example he was setting with his life. How his words in general showed that he was a stellar American, and that he was going to jail as a very deliberate choice – because he thought it was the right thing to do. There was no question in my mind that my government was involved in an unjust war that was going to continue and get larger. Thousands of young men were dying each year. I left the auditorium and found a deserted men's room. I sat on the floor and cried for over an hour, just sobbing. The only time in my life I've reacted to something like that.

Reflecting on Kehler's decision, Ellsberg added:

Randy Kehler never thought his going to prison would end the war. If I hadn't met Randy Kehler it wouldn't have occurred to me to copy [the Pentagon Papers]. His actions spoke to me as no mere words would have done. He put the right question in my mind at the right time.

After leaving RAND, Ellsberg was employed as a senior research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Center for International Studies from 1970 to 1972.

In a 2002 memoir, Ellsberg wrote about the Vietnam War, stating that:

It was no more a "civil war" after 1955 or 1960 than it had been during the U.S.–supported French attempt at colonial reconquest. A war in which one side was entirely equipped and paid by a foreign power – which dictated the nature of the local regime in its own interest – was not a civil war. To say that we had "interfered" in what is "really a civil war," as most American academic writers and even liberal critics of the war do to this day, simply screened a more painful reality and was as much a myth as the earlier official one of "aggression from the North." In terms of the UN Charter and of our own avowed ideals, it was a war of foreign aggression, American aggression.

The Pentagon Papers

In late 1969, with the assistance of his former RAND Corporation colleague Anthony Russo, Ellsberg secretly made several sets of photocopies of the classified documents to which he had access; these later became known as the Pentagon Papers. They revealed that, early on, the government had knowledge that the war as then resourced could most likely not be won. Further, as an editor of The New York Times was to write much later, these documents "demonstrated, among other things, that the Johnson Administration had systematically lied, not only to the public but also to Congress, about a subject of transcendent national interest and significance".

Shortly after Ellsberg copied the documents, he resolved to meet some of the people who had influenced both his change of heart on the war and his decision to act. One of them was Randy Kehler. Another was the poet Gary Snyder, whom he had met in Kyoto in 1960, and with whom he had argued about U.S. foreign policy; Ellsberg was finally prepared to concede that Snyder had been right, about both the situation and the need for action against it.

Release and publication

Throughout 1970, Ellsberg covertly attempted to persuade a few sympathetic U.S. Senators—among them J. William Fulbright, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and George McGovern, a leading opponent of the war—to release the papers on the Senate floor, because a Senator could not be prosecuted for anything he said on the record before the Senate.

Ellsberg allowed some copies of the documents to circulate privately, including among scholars at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), Marcus Raskin and Ralph Stavins. Ellsberg also shared the documents with The New York Times correspondent and former Vietnam-era acquaintance Neil Sheehan, who wrote a story based on what he had received both directly from Ellsberg and from contacts at IPS. While Ellsberg had asked him to only take notes of the documents in his apartment, Sheehan defied Ellsberg's wishes on March 2, by frantically copying them in various Boston-area shops while Ellsberg was vacationing in the West Indies. Sheehan then flew the copies to his home in Washington and then New York.

On Sunday, June 13, 1971, The New York Times published the first of nine excerpts from, and commentaries on, the 7,000-page collection. For 15 days, The New York Times was prevented from publishing its articles by court order requested by the Nixon administration. Meanwhile, while eluding an FBI manhunt for thirteen days, Ellsberg gave the documents to Ben Bagdikian, then-national editor of The Washington Post and former RAND Corporation colleague, in a Boston-area motel. On June 30, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the resumption of publication by The New York Times (New York Times Co. v. United States). Two days prior to the Supreme Court's decision, Ellsberg publicly admitted his role in releasing the Pentagon Papers to the press, and surrendered to federal authorities at the U.S. Attorney's office in Boston.

On June 29, 1971, U.S. Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska entered 4,100 pages of the Papers into the record of his Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds—pages which he had received from Ellsberg via Ben Bagdikian on June 26.

Fallout

The release of these papers was politically embarrassing not only to those involved in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, but also to the incumbent Nixon administration. Nixon's Oval Office tape from June 14, 1971, shows H. R. Haldeman describing the situation to Nixon:

Rumsfeld was making this point this morning... To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing.... You can't trust the government; you can't believe what they say; and you can't rely on their judgment; and the—the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because It shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it's wrong, and the president can be wrong.

John Mitchell, Nixon's Attorney General, almost immediately issued a telegram to The New York Times ordering that it halt publication. The New York Times refused, and the government brought suit against it.

Although The New York Times eventually won the case before the Supreme Court, prior to that, an appellate court ordered that the New York Times temporarily halt further publication. This was the first time the federal government was able to restrain the publication of a major newspaper since the presidency of Abraham Lincoln during the U.S. Civil War. Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers to seventeen other newspapers in rapid succession. The right of the press to publish the papers was upheld in New York Times Co. v. United States. The Supreme Court ruling has been called one of the "modern pillars" of First Amendment rights with respect to freedom of the press.

In response to the leaks, Nixon White House staffers began a campaign against further leaks and against Ellsberg personally. Aides Egil Krogh and David Young, under the supervision of John Ehrlichman, created the "White House Plumbers", which would later lead to the Watergate burglaries. Richard Holbrooke, a friend of Ellsberg, came to see him as "one of those accidental characters of history who show the pattern of a whole era" and thought that he was the "triggering mechanism for events which would link Vietnam and Watergate in one continuous 1961-to-1975 story."

Fielding break-in

In August 1971, Krogh and Young met with G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt in a basement office in the Old Executive Office Building. Hunt and Liddy recommended a "covert operation" to get a "mother lode" of information about Ellsberg's mental state to discredit him. Krogh and Young sent a memo to Ehrlichman seeking his approval for a "covert operation [to] be undertaken to examine all of the medical files still held by Ellsberg's psychiatrist", Lewis Fielding. Ehrlichman approved under the condition that it be "done under your assurance that it is not traceable."

On September 3, 1971, the burglary of Fielding's office—titled "Hunt/Liddy Special Project No. 1" in Ehrlichman's notes—was carried out by White House Plumbers Hunt, Liddy, Eugenio Martínez, Felipe de Diego, and Bernard Barker (the latter three were, or had been, recruited CIA agents). The Plumbers found Ellsberg's file, but it apparently did not contain the potentially embarrassing information they sought, as they left it discarded on the floor of Fielding's office. Hunt and Liddy subsequently planned to break into Fielding's home, but Ehrlichman did not approve the second burglary. The break-in was not known to Ellsberg or to the public until it came to light during Ellsberg's and Russo's trial in April 1973.

Trial and dismissal

On June 28, 1971, two days before a Supreme Court ruling saying that a federal judge had ruled incorrectly about the right of The New York Times to publish the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg publicly surrendered to the United States Attorney's Office for the District of Massachusetts in Boston. In admitting to giving the documents to the press, Ellsberg said:

I felt that as an American citizen, as a responsible citizen, I could no longer cooperate in concealing this information from the American public. I did this clearly at my own jeopardy and I am prepared to answer to all the consequences of this decision.

He and Russo faced charges under the Espionage Act of 1917 and other charges including theft and conspiracy, carrying a total maximum sentence of 115 years for Ellsberg and 35 years for Russo. Their trial commenced in Los Angeles on January 3, 1973, presided over by U.S. District Judge William Matthew Byrne Jr. Ellsberg tried to claim that the documents were "illegally" classified to keep them not from an enemy, but from the American public. However, that argument was ruled "irrelevant", and Ellsberg was silenced before he could begin. In a 2014 interview, Ellsberg stated that his "lawyer, exasperated, said he 'had never heard of a case where a defendant was not permitted to tell the jury why he did what he did.' The judge responded: 'Well, you're hearing one now'. And so it has been with every subsequent whistleblower under indictment".

In spite of being effectively denied a defense, Ellsberg began to see events turn in his favor when the break-in of Fielding's office was revealed to Judge Byrne in a memo on April 26; Byrne ordered that it be shared with the defense.

On May 9, further evidence of illegal wiretapping against Ellsberg was revealed in court. The FBI had recorded numerous conversations between Morton Halperin and Ellsberg without a court order, and furthermore the prosecution had failed to share this evidence with the defense. During the trial, Byrne also revealed that he personally met twice with John Ehrlichman, who offered him directorship of the FBI. Byrne said he refused to consider the offer while the Ellsberg case was pending, though he was criticized for even agreeing to meet with Ehrlichman during the case.

Because of the gross governmental misconduct and illegal evidence gathering, and the defense by Leonard Boudin and Harvard Law School professor Charles Nesson, Judge Byrne dismissed all charges against Ellsberg and Russo on May 11, 1973, after the government claimed it had lost records of wiretapping against Ellsberg. Byrne ruled: "The totality of the circumstances of this case which I have only briefly sketched offend a sense of justice. The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case."

As a result of the revelations involving the Watergate scandal, John Ehrlichman, H. R. Haldeman, Richard Kleindienst, and John Dean were forced out of office on April 30, and all would later be convicted of crimes related to Watergate. Egil Krogh later pleaded guilty to conspiracy, and White House counsel Charles Colson pleaded no contest for obstruction of justice in the burglary.

Halperin case

It was also revealed in 1973, during Ellsberg's trial, that the telephone calls of Morton Halperin, a member of the U.S. National Security Council staff suspected of leaking information about the secret U.S. bombing of Cambodia to The New York Times, were being recorded by the FBI at the request of Henry Kissinger to J. Edgar Hoover.

Halperin and his family sued several federal officials, claiming the wiretap violated their Fourth Amendment rights and Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. The court agreed that Richard Nixon, John Mitchell, and H. R. Haldeman had violated the Halperins' Fourth Amendment rights and awarded them $1 in nominal damages.

Plumbers' Ellsberg neutralization proposal

Ellsberg later claimed that after his trial ended, Watergate prosecutor William H. Merrill informed him of an aborted plot by Liddy and the "Plumbers" to have 12 Cuban Americans who had previously worked for the CIA "totally incapacitate" Ellsberg when he appeared at a public rally. It is unclear whether they were meant to assassinate Ellsberg or merely to hospitalize him. In his autobiography, Liddy describes an "Ellsberg neutralization proposal" originating from Howard Hunt, which involved drugging Ellsberg with LSD, by dissolving it in his soup, at a fund-raising dinner in Washington to "have Ellsberg incoherent by the time he was to speak" and thus "make him appear a near burnt-out drug case" and "discredit him". The plot involved waiters from the Miami Cuban community. According to Liddy, when the plan was finally approved, "there was no longer enough lead time to get the Cuban waiters up from their Miami hotels and into place in the Washington Hotel where the dinner was to take place" and the plan was "put into abeyance pending another opportunity."

Activism and views

Ellsberg's first published book was Papers on the War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972). The book included a revised version of Ellsberg's earlier award-winning "The Quagmire Myth and the Stalemate Machine", originally published in Public Policy, and ends with "The Responsibility of Officials in a Criminal War".

After the Vietnam War, Ellsberg continued his political activism, giving lecture tours and speaking out about current events. Reflecting on his time in government, Ellsberg said the following, based on his extensive access to classified material:

The public is lied to every day by the President, by his spokespeople, by his officers. If you can't handle the thought that the President lies to the public for all kinds of reasons, you couldn't stay in the government at that level, or you're made aware of it, a week. ... The fact is Presidents rarely say the whole truth—essentially, never say the whole truth—of what they expect and what they're doing and what they believe and why they're doing it and rarely refrain from lying, actually, about these matters.

Release of classified documents proposing 1958 nuclear attack on China

On May 22, 2021, during the Biden administration, The New York Times reported Ellsberg had released classified documents revealing the Pentagon in 1958 drew up plans to launch a nuclear attack on China amid tensions over the Taiwan Strait. According to the documents, US military leaders supported a first-use nuclear strike even though they believed China's ally, the Soviet Union, would retaliate and millions of people would perish. Ellsberg told The New York Times he copied the classified documents about the Taiwan Strait crisis fifty years earlier when he copied the Pentagon Papers, but chose not to release the documents then. Instead, Ellsberg released the documents in the spring of 2021 because he said he was concerned about mounting tensions between the U.S. and China over the fate of Taiwan. He assumed the Pentagon was involved again in contingency planning for a nuclear strike on China should a military conflict with conventional weapons fail to deliver a decisive victory. "I do not believe the participants were more stupid or thoughtless than those in between or in the current cabinet", said Ellsberg, who urged President Biden, Congress and the public to take notice.

In releasing the classified documents, Ellsberg offered himself as a defendant in a test case challenging the U.S. Justice Department's use of the Espionage Act of 1917 to punish whistleblowers. Ellsberg noted the Act applies to everyone, not just spies, and prohibits a defendant from explaining the reasons for revealing classified information in the public interest.

Anti-war activism

In an interview with Democracy Now on May 18, 2018, Ellsberg was critical of U.S. intervention overseas especially in the Middle East, stating, "I think, in Iraq, America has never faced up to the number of people who have died because of our invasion, our aggression against Iraq, and Afghanistan over the last 30 years, since we first inspired a CIA-sponsored jihad against the Soviets there, and led to the invasion by the Soviets. What we've done to the Middle East has been hell."

Activism against US-led war against Iraq

During the runup to the 2003 invasion of Iraq he warned of a possible "Tonkin Gulf scenario" that could be used to justify going to war, and called on government "insiders" to go public with information to counter the Bush administration's pro-war propaganda campaign, praising Scott Ritter for his efforts in that regard. He later supported the whistleblowing efforts of British GCHQ translator Katharine Gun and called on others to leak any papers that reveal government deception about the invasion. Ellsberg also testified at the 2004 conscientious objector hearing of Camilo Mejia at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Ellsberg was arrested, in November 2005, for violating a county ordinance for trespassing while protesting against George W. Bush's conduct of the Iraq War.

Ellsberg criticized the arrest of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who had exposed U.S. war crimes in Iraq.

Activism against US military action against Iran

In September 2006, Ellsberg wrote in Harper's Magazine that he hoped someone would leak information about a potential U.S. invasion of Iran before the invasion happened, to stop the war.

In a speech on March 30, 2008, in San Francisco's Unitarian Universalist church, Ellsberg observed that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi does not have the authority to declare impeachment "off the table", as she had done with respect to George W. Bush. The oath of office taken by members of congress requires them to "defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic". He also pointed out that under Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, treaties, including the United Nations Charter and international labor rights accords that the United States has signed, become the supreme law of the land that neither the states, the president, nor the congress have the power to break. For example, if the Congress votes to authorize an unprovoked attack on a sovereign nation, that authorization would not make the attack legal. A president citing the authorization as just cause could be prosecuted in the International Criminal Court for war crimes.

Russian invasion of Ukraine

In April 2022, Ellsberg said that Russian President Vladimir Putin "is a bad guy, very clearly. His aggression is murderous and as illegitimate as the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Or the US invasion of Afghanistan or Iraq. Or Hitler's invasion of Poland." He compared Putin's nuclear threats to Richard Nixon's self-proclaimed "madman strategy". He expressed concern that global cooperation among major powers on climate change and nuclear arms reduction would be impossible.

In April 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ellsberg appeared on Al Jazeera's Upfront and stated that major arms manufacturers, such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin or General Electric, were profiting from the war in Ukraine and from the Saudi Arabian–led intervention in Yemen, saying that "A failing war is just as profitable as a winning one," "It's the old Latin slogan, Cui Bono, who benefits?", "We're not after all a European nation and we have no particular role in the European Union. But in NATO—that's as the Mafia says Cosa Nostra, our thing—we control NATO pretty much and NATO gives us an excuse and a reason to sell enormous amounts of arms to now to the formerly Warsaw Pact nations," and, "Russia is an indispensable enemy." He said both the United States and Russia have their military-industrial complexes.

In June 2022, he said that "The Russian invasion of Ukraine has made the world far more dangerous, not only in the short run, but in ways that may be irreversible. It is a tragic and criminal attack. We are seeing humanity at its almost worst, but not quite the worst — so far, since 1945 we haven't seen nuclear war."

Support for American whistleblowers

Ellsberg said that in regard to former FBI translator turned whistleblower Sibel Edmonds, what she has is "far more explosive than the Pentagon Papers". He also participated in the National Security Whistleblowers Coalition founded by Edmonds, and in 2008, he condemned many U.S. media outlets for purportedly ignoring articles about Edmonds's allegations regarding nuclear proliferation published in The Sunday Times.

On December 9, 2010, Ellsberg appeared on The Colbert Report where he commented that the existence of WikiLeaks helps to build a better government.

On March 21, 2011, Ellsberg, along with 35 other demonstrators, was arrested during a demonstration outside the Marine Corps Base Quantico, in protest of Chelsea Manning's current detention at Marine Corps Brig, Quantico.

On June 10, 2013, Ellsberg published an editorial in The Guardian newspaper praising the actions of former Booz Allen worker Edward Snowden in revealing top-secret surveillance programs of the NSA. Ellsberg believed that the United States had fallen into an "abyss" of total tyranny, but said that because of Snowden's revelations, "I see the unexpected possibility of a way up and out of the abyss."

In June 2013, Ellsberg and numerous celebrities appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning.

In June 2010, Ellsberg was interviewed regarding the parallels between his actions in releasing the Pentagon Papers and those of Manning, who was arrested by the U.S. military in Iraq after allegedly providing to WikiLeaks a classified video showing U.S. military helicopter gunships strafing and killing Iraqis alleged to be civilians. Ellsberg said that he fears for Manning and for Julian Assange, as he feared for himself after the initial publication of the Pentagon Papers. WikiLeaks initially said it had not received the cables, but did plan to post the video of an attack that killed 86 to 145 Afghan civilians in the village of Garani. Ellsberg expressed hope that either Assange or President Obama would post the video, and expressed his strong support for Assange and Manning, whom he called "two new heroes of mine".

Democracy Now! devoted a substantial portion of its July 4, 2013, program to "How the Pentagon Papers Came to be Published By the Beacon Press Told by Daniel Ellsberg & Others." Ellsberg said there are hundreds of public officials right now who know that the public is being lied to about Iran. If they follow orders, they may become complicit in starting an unnecessary war. If they are faithful to their oath to protect the Constitution of the United States, they could prevent that war. Exposing official lies could however carry a heavy personal cost as they could be imprisoned for unlawful disclosure of classified information.

In 2012, Ellsberg co-founded the Freedom of the Press Foundation. In September 2015, Ellsberg and 27 members of the Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity steering group wrote a letter to the president challenging a recently published book that claimed to rebut the report of the United States Senate Intelligence Committee on the Central Intelligence Agency's use of torture.

In 2020, Ellsberg testified in defense of Assange during Assange's extradition hearings. Ellsberg spoke out vociferously against the threats to press freedom from such whistleblower prosecution.

In a December 2022 interview with BBC News, Ellsberg said that he was given all of the Manning information before it came out in the press by Assange.

Support for Occupy Movement

On November 16, 2011, Ellsberg camped on the UC Berkeley Sproul Plaza as part of an effort to support the Occupy Cal movement.

The Doomsday Machine

In December 2017, Ellsberg published The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. He said that his primary job from 1958 until releasing the Pentagon Papers in 1971 was as a nuclear war planner for United States presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. He concluded that United States nuclear war policy was completely crazy and he could no longer live with himself without doing what he could to expose it, even if it meant he would spend the rest of his life in prison. However, he also felt that as long as the U.S. was still involved in the Vietnam War, the United States electorate would not likely listen to a discussion of nuclear war policy. He therefore copied two sets of documents, planning to release first the Pentagon Papers and later documentation of nuclear war plans. However, the nuclear planning materials were hidden in a landfill and then lost during an unexpected tropical storm.

His overriding concerns were as follows:

- As long as the world maintains large nuclear arsenals, it is not a matter of if, but when, a nuclear war will occur.

- The vast majority of the population of an initiator state would likely starve to death during a "nuclear autumn" or "nuclear winter" if they did not die earlier from retaliation or fallout. If the nuclear war dropped only roughly 100 nuclear weapons on cities, as in a war between India and Pakistan, the effect would be similar to the "Year Without a Summer" that followed the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, except that it would last more like a decade, because soot would not settle out of the stratosphere as quickly as the volcanic debris, and roughly a third of the people worldwide not killed by the nuclear exchange would starve to death, because of the resulting crop failures. However, if more than roughly 2 percent of the U.S. nuclear arsenal were used, the results would more likely be a nuclear winter, leading to the deaths from starvation of 98 percent of people worldwide not killed by the nuclear exchange.

- To preserve the ability of a nuclear-weapon state to retaliate from a "decapitation" attack, every country with nuclear weapons seems to have delegated broadly the authority to respond to an apparent nuclear attack.

As an example of the third concern, Ellsberg discussed an interview he had in 1958 with a major, who commanded a squadron of 12 F-100 fighter-bombers at Kunsan Air Base, South Korea. His aircraft were equipped with Mark 28 thermonuclear weapons with a yield of 1.1 megatons each, roughly half the explosive power of all the bombs dropped by the U.S. in World War II both in Europe and the Pacific. The major said his official orders were to wait for orders from his superiors in Osan Air Base, South Korea, or in Japan before ordering his F-100s into the air. However, the major also said that standard military doctrine required him to protect his forces. That meant that if he had reason to believe that a war had already begun when his communications with Osan and Japan were broken, he was required to launch his dozen F-100s with their thermonuclear weapons. They never practiced that launch, because the risk of an accident was too great. Ellsberg then asked what might happen if he gave such launch orders and the sixth plane succumbed to a thermonuclear accident on the runway. After some thought, the major agreed that the five planes already in the air would likely conclude that a nuclear war had begun, and they would likely deliver their warheads to their preassigned targets.

According to Ellsberg the "nuclear football" carried by an aide near the U.S. president at all times is primarily a piece of political theater, a hoax, to keep the public ignorant of the real problems of nuclear command and control.

In Russia, this included a semi-automatic "Dead Hand" system, whereby a nuclear explosion in Moscow, whether accidental or by a foreign state or terrorists, would induce low-level officers to launch ICBMs toward targets in the U.S., presumed to be the origin of such attacks. The first ICBMs launched in this way "would beep a Go signal to any ICBM sites they passed over", which would launch those other ICBMs without further human intervention.

Nuclear threats by the United States

Ellsberg wrote in his 1981 essay Call to Mutiny that, "every president from Truman to Reagan, with the possible exception of Ford, has felt compelled to consider or direct serious preparations for possible imminent U.S. initiation of tactical or strategic nuclear warfare". Some of these threats were implicit; many were explicit. Many governmental officials and authors claimed that those threats made major contributions to achieving important policy objectives. Ellsberg's examples are summarized in the following table:

| President | Target | Incident |

|---|---|---|

| Truman (1945–1953) | Berlin Blockade (June 24, 1948 – May 12, 1949). | |

| Chinese intervention in the Korean War (October 1950). | ||

| Eisenhower (1953–1961) | Korean War, and Taiwan Strait crises of 1954–55 and 1958. | |

| U.S. offers nuclear support to the French at Dien Bien Phu (1954). | ||

| 1956 Suez Crisis and the 1958–59 Berlin crisis. | ||

| To deter an invasion of Kuwait during the 1958 Lebanon crisis. | ||

| Kennedy (1961–1963) | Berlin Crisis of 1961 and 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. | |

| Johnson (1963–1969) | Battle of Khe Sanh, Vietnam, 1968. | |

| Nixon (1969–1974) | To deter an attack on Chinese nuclear capability, 1969–70, or a Soviet response to possible Chinese intervention against India in the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971, or an intervention in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. | |

| Secret threats of massive escalation of the Vietnam War, including possible use of nuclear weapons, 1969–1972. | ||

| Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 | ||

| Ford (1974–1977) | Korean axe murder incident, in which two US army officers were killed while trying to trim a tree blocking open observation of the Demilitarized Zone. Two days later, the tree was cut to a stump 6 meters tall in a massive show of force that included a B-52 nuclear-capable bomber flying straight toward Pyongyang escorted by high performance fighter aircraft, while a US aircraft carrier task force moved into station just offshore. Ellsberg noted that it might be more accurate to classify this incident not as "nuclear threat" but a "show of force". | |

| Carter (1977–1981) | The Carter Doctrine on the Middle East to deter the Soviets, already in Afghanistan, from moving next door into Iran to try to control the Persian Gulf, through which the majority of the world's oil flowed at that time. | |

| Reagan (1981–1989) | ||

| G. H. W. Bush (1989–1993) | Operation Desert Storm. | |

| Clinton (1993–2001) | Secret threats in 1995 on its nuclear reactor program. | |

| Public warning of a nuclear option against Libya's underground chemical weapons facility in 1996. | ||

| G. W. Bush (2001–2009) and all presidents and leading candidates since | Threats of a nuclear attack against Iran's nuclear program. |

Ellsberg Papers

The University of Massachusetts Amherst acquired Ellsberg's papers.

Personal life and death

Ellsberg was married twice. His first marriage was in 1952 to Carol Cummings, a graduate of Radcliffe (now Harvard College) whose father was a Marine Corps brigadier general. It lasted 13 years before ending in divorce (at her request, as he stated in his memoir Secrets). They have two children, Robert Ellsberg and Mary Ellsberg. In 1970, he married Patricia Marx, daughter of toy maker Louis Marx. They lived for some time afterward in Mill Valley, California. They have a son, Michael Ellsberg, who is an author and journalist.

In February 2023, Ellsberg was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given three to six months to live; he publicly disclosed his diagnosis the following month. Ellsberg died at his home in Kensington, California, on June 16, 2023, at the age of 92.