From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Thích Nhất Hạnh | |

|---|---|

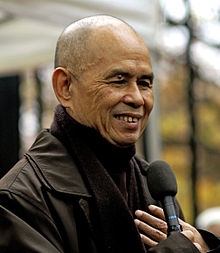

Thich Nhat Hanh in Paris in 2006.

|

|

| Religion | Zen (Thiền) Buddhist |

| School | Lâm Tế Dhyana (Línjì chán) Founder of the Order of Interbeing |

| Lineage | 42nd generation (Lâm Tế) 8th generation (Liễu Quán) |

| Other names | Thầy (teacher) |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Vietnamese |

| Born | October 11, 1926 Thừa Thiên Huế province, Vietnam |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Plum Village (Lang Mai) |

| Title | Thiền Sư (Zen master) |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Thích Chân Thật |

Thích Nhất Hạnh (/ˈtɪk ˈnjʌt ˈhʌn/; Vietnamese: [tʰǐk ɲɜ̌t hɐ̂ʔɲ] (

Nhất Hạnh has published more than 100 books, including more than 40 in English. Nhat Hanh is active in the peace movement, promoting non-violent solutions to conflict[5] and he also refrains from animal product consumption as a means of non-violence towards non-human animals.[6][7]

On 11 November 2014, Nhất Hạnh experienced a severe brain hemorrhage and was brought to a hospital.[8][9] On 3 January 2015 the doctors officially said that he was no longer in a coma and was able to recognize familiar faces.[10] As of 19 February 2015 staff at a rehab facility has reported being able to communicate with Thich Nhat Hanh through eye and arm movement.[11]

Biography

Born as Nguyễn Xuân Bảo, Nhất Hạnh was born in the city of Thừa Thiên Huế in Central Vietnam in 1926. At the age of 16 he entered the monastery at Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế, Vietnam, where his primary teacher was Dhyana (meditation Zen) Master Thanh Quý Chân Thật. [12][13][14] A graduate of Bao Quoc Buddhist Academy in Central Vietnam, Thich Nhat Hanh received training in Zen and the Mahayana school of Buddhism and was ordained as a monk in 1949.[3]

In 1956, he was named editor-in-chief of Vietnamese Buddhism, the periodical of the Unified Vietnam Buddhist Association (Giáo Hội Phật Giáo Việt Nam Thống Nhất). In the following years he founded Lá Bối Press, the Van Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon, and the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS), a neutral corps of Buddhist peaceworkers who went into rural areas to establish schools, build healthcare clinics, and help rebuild villages.[2]

Nhat Hanh is now recognized as a Dharmacharya and as the spiritual head of the Từ Hiếu Temple and associated monasteries.[12][15] On May 1, 1966 at Từ Hiếu Temple, he received the "lamp transmission", making him a Dharmacharya or Dharma Teacher, from Master Chân Thật.[12]

During the Vietnam War

In 1960, Nhat Hanh went to the U.S. to study comparative religion at Princeton University, and was subsequently appointed lecturer in Buddhism at Columbia University. By then he had gained fluency in French, Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali, Japanese and English, in addition to his native Vietnamese. In 1963, he returned to Vietnam to aid his fellow monks in their non-violent peace efforts.Nhat Hanh taught Buddhist psychology and Prajnaparamita literature at the Van Hanh Buddhist University, a private institution that focused on Buddhist studies, Vietnamese culture, and languages. At a meeting in April 1965 Van Hanh Union students issued a Call for Peace statement. It declared: "It is time for North and South Vietnam to find a way to stop the war and help all Vietnamese people live peacefully and with mutual respect." Nhat Hanh left for the U.S. shortly afterwards, leaving Sister Chan Khong in charge of the SYSS. Van Hanh University was taken over by one of the Chancellors who wished to sever ties with Thich Nhat Hanh and the SYSS, accusing Chan Khong of being a communist. From that point the SYSS struggled to raise funds and faced attacks on its members. The SYSS persisted in their relief efforts without taking sides in the conflict.[3]

Nhat Hanh returned to the US in 1966 to lead a symposium in Vietnamese Buddhism at Cornell University and to continue his work for peace. He had written a letter to Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1965 entitled: "In Search of the Enemy of Man". It was during his 1966 stay in the U.S. that Thich Nhat Hanh met with Martin Luther King, Jr. and urged him to publicly denounce the Vietnam War.[16] In 1967, Dr. King gave a famous speech at the Riverside Church in New York City, his first to publicly question the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.[17] Later that year Dr. King nominated Thich Nhat Hanh for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. In his nomination Dr. King said, "I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of [this prize] than this gentle monk from Vietnam. His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity".[18] The fact that King had revealed the candidate he had chosen to nominate and had made a "strong request" to the prize committee, was in sharp violation of the Nobel traditions and protocol.[19][20] The committee did not make an award that year.

In 1969, Nhat Hanh was the delegate for the Buddhist Peace Delegation at the Paris Peace talks. When the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973, Thich Nhat Hanh was denied permission to return to Vietnam and he went into exile in France. From 1976-1977 he led efforts to help rescue Vietnamese boat people in the Gulf of Siam, eventually stopping under pressure from the governments of Thailand and Singapore.[21]

Establishing the Order of Interbeing

Nhat Hanh created the Order of Inter-Being in 1966. He heads this monastic and lay group, teaching Five Mindfulness Trainings and Fourteen Precepts. In 1969, Nhat Hanh established the Unified Buddhist Church (Église Bouddhique Unifiée) in France (not a part of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam). In 1975, he formed the Sweet Potatoes Meditation Center. The center grew and in 1982 he and his colleague Sister Chân Không founded Plum Village Buddhist Center (Làng Mai), a monastery and Practice Center in the Dordogne in the south of France.[2] The Unified Buddhist Church is the legally recognized governing body for Plum Village (Làng Mai) in France, for Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York, the Community of Mindful Living, Parallax Press, Deer Park Monastery in California, Magnolia Village in Batesville, Mississippi, and the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Waldbröl, Germany.[22][23]

He established two monasteries in Vietnam, at the original Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế and at Prajna Temple in the central highlands. Thich Nhat Hanh and the Order of Interbeing have established monasteries and Dharma centers in the United States at Deer Park Monastery (Tu Viện Lộc Uyển) in Escondido, California, Maple Forest Monastery (Tu Viện Rừng Phong) and Green Mountain Dharma Center (Ðạo Tràng Thanh Sơn) in Vermont both of which closed in 2007 and moved to the Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York, and Magnolia Village Practice Center (Đạo Tràng Mộc Lan) in Mississippi. These monasteries are open to the public during much of the year and provide on-going retreats for lay people. The Order of Interbeing also holds retreats for specific groups of lay people, such as families, teenagers, veterans, the entertainment industry, members of Congress, law enforcement officers and people of color.[24][24][25][26][27] He conducted a peace walk in Los Angeles in 2005, and again in 2007.[28]

Notable students of Thich Nhat Hanh include: Skip Ewing founder of the Nashville Mindfulness Center, Natalie Goldberg author and teacher, Joan Halifax founder of the Upaya Institute, Stephanie Kaza environmentalist, Sister Chan Khong Dharma teacher, Noah Levine author, Albert Low Zen teacher and author, Joanna Macy environmentalist and author, John Croft co-creator of Dragon Dreaming, Caitriona Reed Dharma teacher and co-founder of Manzanita Village Retreat Center, Leila Seth author and Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, and Pritam Singh real estate developer and editor of several of Nhat Hanh's books.

Return to Vietnam

In 2005, following lengthy negotiations, Nhat Hanh was given permission from the Vietnamese government to return for a visit. He was also allowed to teach there, publish four of his books in Vietnamese, and travel the country with monastic and lay members of his Order, including a return to his root temple, Tu Hieu Temple in Huế.[4][29] The trip was not without controversy. Thich Vien Dinh, writing on behalf of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (considered illegal by the Vietnamese government), called for Nhat Hanh to make a statement against the Vietnam government's poor record on religious freedom. Thich Vien Dinh feared that the trip would be used as propaganda by the Vietnamese government, suggesting to the world that religious freedom is improving there, while abuses continue.[30][31][32]

Despite the controversy, Nhat Hanh again returned to Vietnam in 2007, while two senior officials of the banned Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV) remained under house arrest. The Unified Buddhist Church called Nhat Hanh's visit a betrayal, symbolizing Nhat Hanh's willingness to work with his co-religionists' oppressors. Vo Van Ai, a spokesman for the UBCV said "I believe Thich Nhat Hanh's trip is manipulated by the Hanoi government to hide its repression of the Unified Buddhist Church and create a false impression of religious freedom in Vietnam." [33] The Plum Village Website states that the three goals of his 2007 trip back to Vietnam were to support new monastics in his Order; to organize and conduct "Great Chanting Ceremonies" intended to help heal remaining wounds from the Vietnam War; and to lead retreats for monastics and lay people. The chanting ceremonies were originally called "Grand Requiem for Praying Equally for All to Untie the Knots of Unjust Suffering", but Vietnamese officials objected, saying it was unacceptable for the government to "equally" pray for soldiers in the South Vietnamese army or U.S. soldiers. Nhat Hanh agreed to change the name to "Grand Requiem For Praying".[33]

Other

In 2014, for the first time in history major Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox Christian leaders, as well as Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist leaders (including Chân Không, representing Nhất Hạnh), met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed calls for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by the year 2020.[34]Approach

Nhat Hanh's approach has been to combine a variety of traditional Zen teachings with insights from other Mahayana Buddhist traditions, methods from Theravada Buddhism, and ideas from Western psychology—to offer a modern light on meditation practice. Hanh's presentation of the Prajñāpāramitā in terms of "interbeing" has doctrinal antecedents in the Huayan school of thought,[35] which "is often said to provide a philosophical foundation" for Zen.[36]

Nhat Hanh has also been a leader in the Engaged Buddhism movement (he coined the term), promoting the individual's active role in creating change. He cites the 13th-century Vietnamese King Trần Nhân Tông with the origination of the concept. Trần Nhân Tông abdicated his throne to become a monk, and founded the Vietnamese Buddhist school in the Bamboo Forest tradition.

Names applied to him

The Vietnamese name Thích (釋) is from "Thích Ca" or "Thích Già" (釋迦), means "of the Shakya (Shakyamuni Buddha) clan."[12] All Buddhist monks and nuns within the East Asian tradition of Mahayana and Zen adopt this name as their "family" name or surname implying that their first family is the Buddhist community. In many Buddhist traditions, there is a progression of names that a person can receive. The first, the lineage name, is given when a person takes refuge in the Three Jewels. Thich Nhat Hanh's lineage name is Trừng Quang. The next is a Dharma name, given when a person, lay or monastic, takes additional vows or when one is ordained as a monastic. Thich Nhat Hanh's Dharma name is Phung Xuan. Additionally, Dharma titles are sometimes given, and Thich Nhat Hanh's Dharma title is "Nhat Hanh".[12]

Neither Nhất (一) nor Hạnh (行)—which approximate the roles of middle name or intercalary name and given name, respectively, when referring to him in English—was part of his name at birth. Nhất (一) means "one", implying "first-class", or "of best quality", in English; Hạnh (行) means "move", implying "right conduct" or "good nature." Thích Nhất Hạnh has translated his Dharma names as Nhất = One, and Hạnh = Action. Vietnamese names follow this naming convention, placing the family or surname first, then the middle or intercalary name which often refers to the person's position in the family or generation, followed by the given name.[37]

Thich Nhat Hanh is often referred to as "Thay" (Vietnamese: Thầy, "master; teacher") or Thay Nhat Hanh by his followers. On the Vietnamese version of the Plum Village website, he is also referred to as Thiền Sư Nhất Hạnh which can be translated as "Zen Master", or "Dhyana Master".[38] Any Vietnamese monk or nun in the Mahayana tradition can be addressed as "Thầy" ("teacher"). Vietnamese Buddhist monks are addressed "Thầy tu" ("monk") and nuns are addressed "Sư Cô" ("Sister") or "Sư Bà" ("Elder Sister").

Awards and honors

Nobel laureate Martin Luther King, Jr. nominated Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967.[18] However, the prize was not awarded to anybody that year.[39] Nhat Hanh was awarded the Courage of Conscience award in 1991.[40]He has been featured in many films, including The Power of Forgiveness showcased at the Dawn Breakers International Film Festival.[41]

Nhat Hanh, along with Alfred Hassler and Sister Chan Khong, became the subject of a graphic novel entitled The Secret of the 5 Powers in 2013.[42]

Writings

- Vietnam: Lotus in a sea of fire. New York, Hill and Wang. 1967.

- Being Peace, Parallax Press, 1987, ISBN 0-938077-00-7

- The Sun My Heart', Parallax Press, 1988, ISBN 0-938077-12-0

- Our Appointment with Life: Sutra on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone , Parallax Press, 1990, ISBN 1-935209-79-5

- The Miracle of Mindfulness, Rider Books, 1991, ISBN 978-0-7126-4787-8

- Old Path White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha, Parallax Press, 1991, ISBN 81-216-0675-6

- Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life, Bantam reissue, 1992, ISBN 0-553-35139-7

- The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusion, Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita [[Diamond Sutra]]], Parallax Press, 1992, ISBN 0-938077-51-1

- 'Hermitage Among the Clouds', Parallax Press, 1993, ISBN 0-938077-56-2

- Zen Keys: A Guide to Zen Practice, Three Leaves, 1994, ISBN 0-385-47561-6

- Cultivating The Mind Of Love, Full Circle, 1996, ISBN 81-216-0676-4

- The Heart Of Understanding, Full Circle, 1997, ISBN 81-216-0703-5

- Transformation and Healing: Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness, Full Circle, 1997, ISBN 81-216-0696-9

- Living Buddha, Living Christ, Riverhead Trade, 1997, ISBN 1-57322-568-1

- True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart, Shambhala, 1997, ISBN 1-59030-404-7

- Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals, 1962-1966, Riverhead Trade, 1999, ISBN 1-57322-796-X

- Going Home: Jesus and Buddha as Brothers, Riverhead Books, 1999, ISBN 1-57322-145-7

- The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching, Broadway Books, 1999, ISBN 0-7679-0369-2

- The Miracle of Mindfulness: A Manual on Meditation, Beacon Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8070-1239-4 (Vietnamese: Phép lạ c̉ua sư t̉inh thưc).

- The Raft Is Not the Shore: Conversations Toward a Buddhist/Christian Awareness, Daniel Berrigan (Co-author), Orbis Books, 2000, ISBN 1-57075-344-X

- The Path of Emancipation: Talks from a 21-Day Mindfulness Retreat, Unified Buddhist Church, 2000, ISBN 81-7621-189-3

- A Pebble in Your Pocket, Full Circle, 2001, ISBN 81-7621-188-5

- Essential Writings, Robert Ellsberg (Editor), Orbis Books, 2001, ISBN 1-57075-370-9

- Anger, Riverhead Trade, 2002, ISBN 1-57322-937-7

- Be Free Where You Are, Parallax Press, 2002, ISBN 1-888375-23-X

- No Death, No Fear, Riverhead Trade reissue, 2003, ISBN 1-57322-333-6

- Touching the Earth: Intimate Conversations with the Buddha, Parallax Press, 2004, ISBN 1-888375-41-8

- Teachings on Love, Full Circle, 2005, ISBN 81-7621-167-2

- Understanding Our Mind, HarperCollins, 2006, ISBN 978-81-7223-796-7

- Buddha Mind, Buddha Body: Walking Toward Enlightenment, Parallax Press, 2007, ISBN 1-888375-75-2

- The Art of Power, HarperOne, 2007, ISBN 0-06-124234-9

- Under the Banyan Tree, Full Circle, 2008, ISBN 81-7621-175-3

- Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life. HarperOne. 2010. ISBN 978-0-06-169769-2.

- Reconciliation: Healing the Inner Child, Parallax Press, 2010, ISBN 1-935209-64-7

- The Novice: A Story of True Love, Unified Buddhist Church, 2011, ISBN 978-0-06-200583-0

- Works by or about Thích Nhất Hạnh in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Your True Home: The Everyday Wisdom of Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Publications, 2011, ISBN 978-1-59030-926-1

- The Pocket Thich Nhat Hanh, Shambhala Pocket Classics, 2012, ISBN 978-1-59030-936-0

- The Art of Communicating, HarperOne, 2013, ISBN 978-0-06-222467-5

- Blooming of a Lotus, Beacon, 2009, ISBN 9780807012383

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering, Parallax Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1937006853