Immanuel Kant, 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher who is a central figure in modern philosophy. In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, he argued that space, time and causation are mere sensibilities; "things-in-themselves" exist, but their nature is unknowable. In his view, the mind shapes and structures experience, with all human experience sharing certain structural features. He drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposition that worldly objects can be intuited a priori ("beforehand"), and that intuition is therefore independent from objective reality. Kant believed that reason is the source of morality, and that aesthetics arise from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant's views continue to have a major influence on contemporary philosophy, especially the fields of epistemology, ethics, political theory, and post-modern aesthetics.

In one of Kant's major works, the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), he attempted to explain the relationship between reason and human experience and to move beyond the failures of traditional philosophy and metaphysics. Kant wanted to put an end to an era of futile and speculative theories of human experience, while resisting the skepticism of thinkers such as David Hume. Kant regarded himself as showing the way past the impasse between rationalists and empiricists which philosophy had led to, and is widely held to have synthesized both traditions in his thought.

Kant was an exponent of the idea that perpetual peace could be secured through universal democracy and international cooperation. He believed that this would be the eventual outcome of universal history, although it is not rationally planned. The nature of Kant's religious ideas continues to be the subject of philosophical dispute, with viewpoints ranging from the impression that he was an initial advocate of atheism who at some point developed an ontological argument for God, to more critical treatments epitomized by Nietzsche, who claimed that Kant had "theologian blood" and was merely a sophisticated apologist for traditional Christian faith.

Kant published other important works on ethics, religion, law, aesthetics, astronomy, and history. These include the Universal Natural History (1755), the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), the Metaphysics of Morals (1797), and the Critique of Judgment (1790), which looks at aesthetics and teleology.

Biography

Kant's mother, Anna Regina Reuter (1697–1737), was born in Königsberg (since 1946 the city of Kaliningrad, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia) to a father from Nuremberg.

(Her surname is sometimes erroneously given as Porter.) Kant's father,

Johann Georg Kant (1682–1746), was a German harness maker from Memel, at the time Prussia's most northeastern city (now Klaipėda, Lithuania). Immanuel Kant believed that his paternal grandfather Hans Kant was of Scottish origin.

While scholars of Kant's life long accepted the claim, there is no

evidence that Kant's paternal line was Scottish; it is more likely that

the Kants got their name from the village of Kantwaggen (today part of Priekulė) and were of Curonian origin. Kant was the fourth of nine children (four of whom reached adulthood).

Kant was born on April 22, 1724 into a Prussian German family of Lutheran Protestant faith in Königsberg, East Prussia. Baptized 'Emanuel', he later changed his name to 'Immanuel' after learning Hebrew. He was brought up in a Pietist household that stressed religious devotion, humility, and a literal interpretation of the Bible. His education was strict, punitive and disciplinary, and focused on Latin and religious instruction over mathematics and science. Kant maintained Christian ideals for some time, but struggled to reconcile the faith with his belief in science. In his Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, he reveals a belief in immortality as the necessary condition of humanity's approach to the highest morality possible. However, as Kant was skeptical about some of the arguments used prior to him in defense of theism and maintained that human understanding is limited and can never attain knowledge about God or the soul, various commentators have labelled him a philosophical agnostic.

Common myths about Kant's personal mannerisms are listed,

explained, and refuted in Goldthwait's introduction to his translation

of Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime.

It is often held that Kant lived a very strict and disciplined life,

leading to an oft-repeated story that neighbors would set their clocks

by his daily walks. He never married, but seemed to have a rewarding

social life — he was a popular teacher and a modestly successful author

even before starting on his major philosophical works. He had a circle

of friends with whom he frequently met, among them Joseph Green, an English merchant in Königsberg.

A common myth is that Kant never traveled more than 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) from Königsberg his whole life. In fact, between 1750 and 1754 he worked as a tutor (Hauslehrer) in Judtschen (now Veselovka, Russia, approximately 20 km) and in Groß-Arnsdorf (now Jarnołtowo near Morąg (German: Mohrungen), Poland, approximately 145 km).

Young scholar

Kant showed a great aptitude for study at an early age. He first attended the Collegium Fridericianum from which he graduated at the end of the summer of 1740. In 1740, aged 16, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg, where he spent his whole career. He studied the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and Christian Wolff under Martin Knutzen (Associate Professor of Logic and Metaphysics from 1734 until his death in 1751), a rationalist

who was also familiar with developments in British philosophy and

science and introduced Kant to the new mathematical physics of Isaac Newton. Knutzen dissuaded Kant from the theory of pre-established harmony, which he regarded as "the pillow for the lazy mind". He also dissuaded Kant from idealism,

the idea that reality is purely mental, which most philosophers in the

18th century regarded in a negative light. The theory of transcendental idealism that Kant later included in the Critique of Pure Reason was developed partially in opposition to traditional idealism.

His father's stroke and subsequent death in 1746 interrupted his studies. Kant left Königsberg shortly after August 1748—he would return there in August 1754.

He became a private tutor in the towns surrounding Königsberg, but

continued his scholarly research. In 1749, he published his first

philosophical work, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces (written in 1745–47).

Early work

Kant is best known for his work in the philosophy of ethics and metaphysics, but he made significant contributions to other disciplines. He won the Berlin Academy Prize in 1754 for his argument that the Moon's gravity would eventually cause its tidal locking to coincide with the Earth's rotation. The next year, he expanded this reasoning to the formation and evolution of the Solar System in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens.

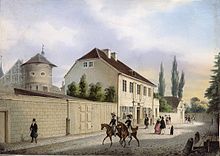

Kant's house in Königsberg

In the Universal Natural History, Kant laid out the Nebular hypothesis, in which he deduced that the Solar System had formed from a large cloud of gas, a nebula. Kant also correctly deduced that the Milky Way was a large disk of stars,

which he theorized formed from a much larger spinning gas cloud. He

further suggested that other distant "nebulae" might be other galaxies.

These postulations opened new horizons for astronomy, for the first time

extending it beyond the Solar System to galactic and intergalactic

realms. According to Thomas Huxley (1867), Kant also made contributions to geology in his Universal Natural History, and according to Lord Kelvin (1897), he made contributions useful to mathematicians and astronomers.

From then on, Kant turned increasingly to philosophical issues,

although he continued to write on the sciences throughout his life. In

the early 1760s, Kant produced a series of important works in

philosophy. The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures, a work in logic, was published in 1762. Two more works appeared the following year: Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy and The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God. In 1764, Kant wrote Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime and then was second to Moses Mendelssohn in a Berlin Academy prize competition with his Inquiry Concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality (often referred to as "The Prize Essay"). In 1766 Kant wrote Dreams of a Spirit-Seer which dealt with the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. The exact influence of Swedenborg on Kant, as well as the extent of Kant's belief in mysticism according to Dreams of a Spirit-Seer, remain controversial. On 31 March 1770, aged 45, Kant was finally appointed Full Professor of Logic and Metaphysics (Professor Ordinarius der Logic und Metaphysic) at the University of Königsberg. In defense of this appointment, Kant wrote his inaugural dissertation (Inaugural-Dissertation) De Mundi Sensibilis atque Intelligibilis Forma et Principiis (On the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World).

This work saw the emergence of several central themes of his mature

work, including the distinction between the faculties of intellectual

thought and sensible receptivity. To miss this distinction would mean to

commit the error of subreption, and, as he says in the last chapter of the dissertation, only in avoiding this error does metaphysics flourish.

The issue that vexed Kant was central to what 20th-century scholars called "the philosophy of mind".

The flowering of the natural sciences had led to an understanding of

how data reaches the brain. Sunlight falling on an object is reflected

from its surface in a way that maps the surface features (color,

texture, etc.). The reflected light reaches the human eye, passes

through the cornea, is focused by the lens onto the retina where it

forms an image similar to that formed by light passing through a pinhole

into a camera obscura. The retinal cells send impulses through the optic nerve

and then they form a mapping in the brain of the visual features of the

object. The interior mapping is not the exterior object, and our belief

that there is a meaningful relationship between the object and the

mapping in the brain depends on a chain of reasoning that is not fully

grounded. But the uncertainty aroused by these considerations, by

optical illusions, misperceptions, delusions, etc., are not the end of

the problems.

Kant saw that the mind could not function as an empty container

that simply receives data from outside. Something must be giving order

to the incoming data. Images of external objects must be kept in the

same sequence in which they were received. This ordering occurs through

the mind's intuition of time. The same considerations apply to the

mind's function of constituting space for ordering mappings of visual

and tactile signals arriving via the already described chains of

physical causation.

It is often claimed that Kant was a late developer, that he only

became an important philosopher in his mid-50s after rejecting his

earlier views. While it is true that Kant wrote his greatest works

relatively late in life, there is a tendency to underestimate the value

of his earlier works. Recent Kant scholarship has devoted more attention

to these "pre-critical" writings and has recognized a degree of

continuity with his mature work.

Work hiatus

At age 46, Kant was an established scholar and an increasingly influential philosopher, and much was expected of him.

In correspondence with his ex-student and friend Markus Herz,

Kant admitted that, in the inaugural dissertation, he had failed to

account for the relation between our sensible and intellectual

faculties. He needed to explain how we combine what is known as sensory

knowledge with the other type of knowledge—i.e. reasoned knowledge—these

two being related but having very different processes.

Kant also credited David Hume with awakening him from a "dogmatic slumber".

Hume had stated that experience consists only of sequences of feelings,

images or sounds. Ideas such as "cause", goodness, or objects were not

evident in experience, so why do we believe in the reality of these?

Kant felt that reason could remove this skepticism, and he set himself

to solving these problems. He did not publish any work in philosophy for

the next 11 years.

Immanuel Kant

Although fond of company and conversation with others, Kant isolated

himself, and resisted friends' attempts to bring him out of his

isolation. It has been noted that in 1778, in response to one of these

offers by a former pupil, Kant wrote:

Any change makes me apprehensive, even if it offers the greatest promise of improving my condition, and I am persuaded by this natural instinct of mine that I must take heed if I wish that the threads which the Fates spin so thin and weak in my case to be spun to any length. My great thanks, to my well-wishers and friends, who think so kindly of me as to undertake my welfare, but at the same time a most humble request to protect me in my current condition from any disturbance.

When Kant emerged from his silence in 1781, the result was the Critique of Pure Reason. Although now uniformly recognized as one of the greatest works in the history of philosophy, this Critique

was largely ignored upon its initial publication. The book was long,

over 800 pages in the original German edition, and written in a

convoluted style. It received few reviews, and these granted it no

significance. Kant's former student, Johann Gottfried Herder

criticized it for placing reason as an entity worthy of criticism

instead of considering the process of reasoning within the context of

language and one's entire personality. Similar to Christian Garve and Johann Georg Heinrich Feder,

he rejected Kant's position that space and time possessed a form that

could be analyzed. Additionally, Garve and Feder also faulted Kant's

Critique for not explaining differences in perception of sensations. Its density made it, as Herder said in a letter to Johann Georg Hamann, a "tough nut to crack", obscured by "all this heavy gossamer". Its reception stood in stark contrast to the praise Kant had received for earlier works, such as his Prize Essay and shorter works that preceded the first Critique. These well-received and readable tracts include one on the earthquake in Lisbon that was so popular that it was sold by the page. Prior to the change in course documented in the first Critique, his books sold well, and by the time he published Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime in 1764 he had become a notable popular author.

Kant was disappointed with the first Critique's reception. Recognizing

the need to clarify the original treatise, Kant wrote the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics

in 1783 as a summary of its main views. Shortly thereafter, Kant's

friend Johann Friedrich Schultz (1739–1805) (professor of mathematics)

published Erläuterungen über des Herrn Professor Kant Critik der reinen Vernunft (Königsberg, 1784), which was a brief but very accurate commentary on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason.

Kant's reputation gradually rose through the latter portion of

the 1780s, sparked by a series of important works: the 1784 essay, "Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?"; 1785's Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (his first work on moral philosophy); and, from 1786, Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. But Kant's fame ultimately arrived from an unexpected source. In 1786, Karl Leonhard Reinhold

published a series of public letters on Kantian philosophy. In these

letters, Reinhold framed Kant's philosophy as a response to the central

intellectual controversy of the era: the Pantheism Dispute. Friedrich Jacobi had accused the recently deceased Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (a distinguished dramatist and philosophical essayist) of Spinozism. Such a charge, tantamount to atheism, was vigorously denied by Lessing's friend Moses Mendelssohn, leading to a bitter public dispute among partisans. The controversy gradually escalated into a debate about the values of the Enlightenment and the value of reason.

Reinhold maintained in his letters that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason could settle this dispute by defending the authority and bounds of reason. Reinhold's letters were widely read and made Kant the most famous philosopher of his era.

Later work and death

Kant published a second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (Kritik der reinen Vernunft)

in 1787, heavily revising the first parts of the book. Most of his

subsequent work focused on other areas of philosophy. He continued to

develop his moral philosophy, notably in 1788's Critique of Practical Reason (known as the second Critique) and 1797's Metaphysics of Morals. The 1790 Critique of Judgment (the third Critique) applied the Kantian system to aesthetics and teleology. It was in this critique where Kant wrote one of his most popular statements, "it

is absurd to hope that another Newton will arise in the future who will

make comprehensible to us the production of a blade of grass according

to natural laws".

In 1792, Kant's attempt to publish the Second of the four Pieces of Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason, in the journal Berlinische Monatsschrift, met with opposition from the King's censorship commission, which had been established that same year in the context of the French Revolution.

Kant then arranged to have all four pieces published as a book, routing

it through the philosophy department at the University of Jena to avoid

the need for theological censorship. This insubordination earned him a now famous reprimand from the King.

When he nevertheless published a second edition in 1794, the censor was

so irate that he arranged for a royal order that required Kant never to

publish or even speak publicly about religion. Kant then published his response to the King's reprimand and explained himself, in the preface of The Conflict of the Faculties.

Kant with friends, including Christian Jakob Kraus, Johann Georg Hamann, Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel and Karl Gottfried Hagen

He also wrote a number of semi-popular essays on history, religion,

politics and other topics. These works were well received by Kant's

contemporaries and confirmed his preeminent status in 18th-century

philosophy. There were several journals devoted solely to defending and

criticizing Kantian philosophy. Despite his success, philosophical

trends were moving in another direction. Many of Kant's most important

disciples and followers (including Reinhold, Beck and Fichte)

transformed the Kantian position into increasingly radical forms of

idealism. The progressive stages of revision of Kant's teachings marked

the emergence of German Idealism. Kant opposed these developments and publicly denounced Fichte in an open letter in 1799.

It was one of his final acts expounding a stance on philosophical

questions. In 1800, a student of Kant named Gottlob Benjamin Jäsche

(1762–1842) published a manual of logic for teachers called Logik, which he had prepared at Kant's request. Jäsche prepared the Logik using a copy of a textbook in logic by Georg Friedrich Meier entitled Auszug aus der Vernunftlehre, in which Kant had written copious notes and annotations. The Logik

has been considered of fundamental importance to Kant's philosophy, and

the understanding of it. The great 19th-century logician Charles Sanders Peirce remarked, in an incomplete review of Thomas Kingsmill Abbott's English translation of the introduction to Logik, that "Kant's whole philosophy turns upon his logic." Also, Robert Schirokauer Hartman and Wolfgang Schwarz, wrote in the translators' introduction to their English translation of the Logik, "Its importance lies not only in its significance for the Critique of Pure Reason, the second part of which is a restatement of fundamental tenets of the Logic, but in its position within the whole of Kant's work."

Kant's health, long poor, worsened and he died at Königsberg on 12 February 1804, uttering "Es ist gut (It is good)" before expiring. His unfinished final work was published as Opus Postumum.

Kant wrote a book discussing his theory of virtue in terms of

independence which he believed was "a viable modern alternative to more

familiar Greek views about virtue". This book is often criticized for

its hostile tone and for not articulating his thoughts about autocracy

comprehensibly. In the self-governance model of Aristotelian virtue, the

non-rational part of the soul can be made to listen to reason through

training. Although Kantian self-governance appears to involve "a

rational crackdown on appetites and emotions" with lack of harmony

between reason and emotion, Kantian virtue denies requiring

"self-conquest, self-suppression, or self-silencing". They dispute that

"the self-mastery constitutive of virtue is ultimately mastery over our

tendency of will to give priority to appetite or emotion unregulated by

duty, it does not require extirpating, suppressing, or silencing

sensibility in general".

Philosophy

In Kant's essay "Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?",

Kant defined the Enlightenment as an age shaped by the Latin motto Sapere aude ("Dare to be wise"). Kant maintained that one ought to think autonomously, free of the dictates of external authority. His work reconciled many of the differences between the rationalist and empiricist traditions of the 18th century. He had a decisive impact on the Romantic and German Idealist philosophies of the 19th century. His work has also been a starting point for many 20th century philosophers.

Kant asserted that, because of the limitations of argumentation in the absence of irrefutable evidence,

no one could really know whether there is a God and an afterlife or

not. For the sake of morality and as a ground for reason, Kant asserted,

people are justified in believing in God, even though they could never

know God's presence empirically. He explained:

All the preparations of reason, therefore, in what may be called pure philosophy, are in reality directed to those three problems only [God, the soul, and freedom]. However, these three elements in themselves still hold independent, proportional, objective weight individually. Moreover, in a collective relational context; namely, to know what ought to be done: if the will is free, if there is a God, and if there is a future world. As this concerns our actions with reference to the highest aims of life, we see that the ultimate intention of nature in her wise provision was really, in the constitution of our reason, directed to moral interests only.

Immanuel Kant by Carle Vernet (1758–1836)

The sense of an enlightened approach and the critical method required that "If one cannot prove that a thing is, he may try to prove that it is not. If he fails to do either (as often occurs), he may still ask whether it is in his interest to accept

one or the other of the alternatives hypothetically, from the

theoretical or the practical point of view. Hence the question no longer

is as to whether perpetual peace

is a real thing or not a real thing, or as to whether we may not be

deceiving ourselves when we adopt the former alternative, but we must act on the supposition of its being real."

The presupposition of God, soul, and freedom was then a practical

concern, for "Morality, by itself, constitutes a system, but happiness

does not, unless it is distributed in exact proportion to morality.

This, however, is possible in an intelligible world only under a wise

author and ruler. Reason compels us to admit such a ruler, together with

life in such a world, which we must consider as future life, or else

all moral laws are to be considered as idle dreams... ."

Kant drew a parallel between the Copernican revolution and the epistemology of his new transcendental philosophy. He never used the "Copernican revolution" phrase about himself, but it has often been applied to his work by others.

Kant's Copernican revolution involved two interconnected foundations of his "critical philosophy":

- the epistemology of transcendental idealism and

- the moral philosophy of the autonomy of practical reason.

These teachings placed the active, rational human subject

at the center of the cognitive and moral worlds. Kant argued that the

rational order of the world as known by science was not just the

accidental accumulation of sense perceptions.

Conceptual unification and integration is carried out by the mind through concepts or the "categories of the understanding" operating on the perceptual manifold within space and time. The latter are not concepts, but are forms of sensibility that are a priori

necessary conditions for any possible experience. Thus the objective

order of nature and the causal necessity that operates within it depend

on the mind's processes, the product of the rule-based activity that

Kant called, "synthesis." There is much discussion among Kant scholars about the correct interpretation of this train of thought.

The 'two-world' interpretation regards Kant's position as a

statement of epistemological limitation, that we are not able to

transcend the bounds of our own mind, meaning that we cannot access the "thing-in-itself". However, Kant also speaks of the thing in itself or transcendental object

as a product of the (human) understanding as it attempts to conceive of

objects in abstraction from the conditions of sensibility. Following

this line of thought, some interpreters have argued that the thing in

itself does not represent a separate ontological domain but simply a way

of considering objects by means of the understanding alone – this is

known as the two-aspect view.

The notion of the "thing in itself"

was much discussed by philosophers after Kant. It was argued that

because the "thing in itself" was unknowable, its existence must not be

assumed. Rather than arbitrarily switching to an account that was

ungrounded in anything supposed to be the "real," as did the German

Idealists, another group arose to ask how our (presumably reliable)

accounts of a coherent and rule-abiding universe were actually grounded.

This new kind of philosophy became known as Phenomenology, and its founder was Edmund Husserl.

With regard to morality, Kant argued that the source of the good lies not in anything outside the human subject, either in nature or given by God,

but rather is only the good will itself. A good will is one that acts

from duty in accordance with the universal moral law that the autonomous

human being freely gives itself. This law obliges one to treat

humanity – understood as rational agency, and represented through

oneself as well as others – as an end in itself rather than (merely) as means to other ends the individual might hold. This necessitates practical self-reflection in which we universalize our reasons.

These ideas have largely framed or influenced all subsequent

philosophical discussion and analysis. The specifics of Kant's account

generated immediate and lasting controversy. Nevertheless, his theses –

that the mind itself necessarily makes a constitutive contribution to its knowledge,

that this contribution is transcendental rather than psychological,

that philosophy involves self-critical activity, that morality is rooted

in human freedom, and that to act autonomously is to act according to

rational moral principles – have all had a lasting effect on subsequent

philosophy.

Theory of perception

Kant defines his theory of perception in his influential 1781 work the Critique of Pure Reason, which has often been cited as the most significant volume of metaphysics and epistemology

in modern philosophy. Kant maintains that our understanding of the

external world had its foundations not merely in experience, but in both

experience and a priori concepts, thus offering a non-empiricist critique of rationalist philosophy, which is what has been referred to as his Copernican revolution.

Firstly, Kant distinguishes between analytic and synthetic propositions:

- Analytic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is contained in its subject concept; e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried," or, "All bodies take up space."

- Synthetic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is not contained in its subject concept; e.g., "All bachelors are alone," or, "All bodies have weight."

An analytic proposition is true by nature of the meaning of the words

in the sentence — we require no further knowledge than a grasp of the

language to understand this proposition. On the other hand, a synthetic

statement is one that tells us something about the world. The truth or

falsehood of synthetic statements derives from something outside their

linguistic content. In this instance, weight is not a necessary predicate

of the body; until we are told the heaviness of the body we do not know

that it has weight. In this case, experience of the body is required

before its heaviness becomes clear. Before Kant's first Critique,

empiricists (cf. Hume) and rationalists (cf. Leibniz) assumed that all synthetic statements required experience to be known.

Kant contests this assumption by claiming that elementary mathematics, like arithmetic, is synthetic a priori, in that its statements provide new knowledge not derived from experience. This becomes part of his over-all argument for transcendental idealism. That is, he argues that the possibility of experience depends on certain necessary conditions — which he calls a priori forms — and that these conditions structure and hold true of the world of experience. His main claims in the "Transcendental Aesthetic" are that mathematic judgments are synthetic a priori and that space and time are not derived from experience but rather are its preconditions.

Once we have grasped the functions of basic arithmetic, we do not

need empirical experience to know that 100 + 100 = 200, and so it

appears that arithmetic is analytic. However, that it is analytic can be

disproved by considering the calculation 5 + 7 = 12: there is nothing

in the numbers 5 and 7 by which the number 12 can be inferred. Thus "5 +

7" and "the cube root of 1,728" or "12" are not analytic because their

reference is the same but their sense is not — the statement "5 + 7 =

12" tells us something new about the world. It is self-evident, and

undeniably a priori, but at the same time it is synthetic. Thus Kant proved that a proposition can be synthetic and a priori.

Kant asserts that experience is based on the perception of external objects and a priori knowledge.

The external world, he writes, provides those things that we sense. But

our mind processes this information and gives it order, allowing us to

comprehend it. Our mind supplies the conditions of space and time to

experience objects. According to the "transcendental unity of

apperception", the concepts of the mind (Understanding) and perceptions

or intuitions that garner information from phenomena (Sensibility) are

synthesized by comprehension. Without concepts, perceptions are

nondescript; without perceptions, concepts are meaningless — thus the

famous statement, "Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions

(perceptions) without concepts are blind."

Kant also claims that an external environment is necessary for

the establishment of the self. Although Kant would want to argue that

there is no empirical way of observing the self, we can see the logical

necessity of the self when we observe that we can have different

perceptions of the external environment over time. By uniting these

general representations into one global representation, we can see how a

transcendental self emerges. "I am therefore conscious of the identical

self in regard to the manifold of the representations that are given to

me in an intuition because I call them all together my

representations."

Categories of the Faculty of Understanding

Kant statue in Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Kant deemed it obvious that we have some objective knowledge of the

world, such as, say, Newtonian physics. But this knowledge relies on synthetic, a priori laws of nature, like causality and substance. How is this possible? Kant's solution was that the subject must supply laws that make experience of objects possible, and that these laws are synthetic, a priori

laws of nature that apply to all objects before we experience them. To

deduce all these laws, Kant examined experience in general, dissecting

in it what is supplied by the mind from what is supplied by the given

intuitions. This is commonly called a transcendental deduction.

To begin with, Kant's distinction between the a posteriori being contingent and particular knowledge, and the a priori

being universal and necessary knowledge, must be kept in mind. If we

merely connect two intuitions together in a perceiving subject, the

knowledge is always subjective because it is derived a posteriori,

when what is desired is for the knowledge to be objective, that is, for

the two intuitions to refer to the object and hold good of it for

anyone at any time, not just the perceiving subject in its current

condition. What else is equivalent to objective knowledge besides the a priori, (universal and necessary knowledge)? Before knowledge can be objective, it must be incorporated under an a priori category of understanding.

For example, if a subject says, "The sun shines on the stone; the

stone grows warm," all he perceives are phenomena. His judgment is

contingent and holds no necessity. But if he says, "The sunshine causes

the stone to warm," he subsumes the perception under the category of

causality, which is not found in the perception, and necessarily

synthesizes the concept sunshine with the concept heat, producing a

necessarily universally true judgment.

To explain the categories in more detail, they are the

preconditions of the construction of objects in the mind. Indeed, to

even think of the sun and stone presupposes the category of subsistence,

that is, substance. For the categories synthesize the random data of

the sensory manifold into intelligible objects. This means that the

categories are also the most abstract things one can say of any object

whatsoever, and hence one can have an a priori cognition of the

totality of all objects of experience if one can list all of them. To do

so, Kant formulates another transcendental deduction.

Judgments are, for Kant, the preconditions of any thought. Man

thinks via judgments, so all possible judgments must be listed and the

perceptions connected within them put aside, so as to make it possible

to examine the moments when the understanding is engaged in

constructing judgments. For the categories are equivalent to these

moments, in that they are concepts of intuitions in general, so far as

they are determined by these moments universally and necessarily. Thus

by listing all the moments, one can deduce from them all of the

categories.

One may now ask: How many possible judgments are there? Kant believed that all the possible propositions within Aristotle's syllogistic

logic are equivalent to all possible judgments, and that all the

logical operators within the propositions are equivalent to the moments

of the understanding within judgments. Thus he listed Aristotle's system

in four groups of three: quantity (universal, particular, singular),

quality (affirmative, negative, infinite), relation (categorical,

hypothetical, disjunctive) and modality (problematic, assertoric,

apodeictic). The parallelism with Kant's categories is obvious: quantity

(unity, plurality, totality), quality (reality, negation, limitation),

relation (substance, cause, community) and modality (possibility,

existence, necessity).

The fundamental building blocks of experience, i.e. objective

knowledge, are now in place. First there is the sensibility, which

supplies the mind with intuitions, and then there is the understanding,

which produces judgments of these intuitions and can subsume them under

categories. These categories lift the intuitions up out of the subject's

current state of consciousness and place them within consciousness in

general, producing universally necessary knowledge. For the categories

are innate in any rational being, so any intuition thought within a

category in one mind is necessarily subsumed and understood identically

in any mind. In other words, we filter what we see and hear.

Transcendental schema doctrine

Kant ran into a problem with his theory that the mind plays a part in

producing objective knowledge. Intuitions and categories are entirely

disparate, so how can they interact? Kant's solution is the

(transcendental) schema: a priori principles by which the transcendental

imagination connects concepts with intuitions through time. All the

principles are temporally bound, for if a concept is purely a priori, as

the categories are, then they must apply for all times. Hence there are

principles such as substance is that which endures through time, and the cause must always be prior to the effect.

Moral philosophy

Kant developed his moral philosophy in three works: Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785), Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and Metaphysics of Morals (1797).

In Groundwork, Kant' tries to convert our everyday, obvious, rational

knowledge of morality into philosophical knowledge. The latter two

works used "practical reason", which is based only on things about which

reason can tell us, and not deriving any principles from experience, to

reach conclusions which can be applied to the world of experience (in

the second part of The Metaphysic of Morals).

Kant is known for his theory that there is a single moral obligation, which he called the "Categorical Imperative", and is derived from the concept of duty.

Kant defines the demands of moral law as "categorical imperatives".

Categorical imperatives are principles that are intrinsically valid;

they are good in and of themselves; they must be obeyed in all

situations and circumstances, if our behavior is to observe the moral

law. The Categorical Imperative provides a test against which moral

statements can be assessed. Kant also stated that the moral means and

ends can be applied to the categorical imperative, that rational beings

can pursue certain "ends" using the appropriate "means". Ends based on

physical needs or wants create hypothetical imperatives.

The categorical imperative can only be based on something that is an

"end in itself", that is, an end that is not a means to some other need,

desire, or purpose. Kant believed that the moral law is a principle of reason

itself, and is not based on contingent facts about the world, such as

what would make us happy, but to act on the moral law which has no other

motive than "worthiness of being happy". Accordingly, he believed that moral obligation applies only to rational agents.

Unlike a hypothetical imperative, a categorical imperative is an

unconditional obligation; it has the force of an obligation regardless

of our will or desires In Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785) Kant enumerated three formulations of the categorical imperative that he believed to be roughly equivalent. In the same book, Kant stated:

- Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.

According to Kant, one cannot make exceptions for oneself. The

philosophical maxim on which one acts should always be considered to be a

universal law without exception. One cannot allow oneself to do a

particular action unless one thinks it appropriate that the reason for

the action should become a universal law. For example, one should not

steal, however dire the circumstances—because, by permitting oneself to

steal, one makes stealing a universally acceptable act. This is the

first formulation of the categorical imperative, often known as the

universalizability principle.

Kant believed that, if an action is not done with the motive of

duty, then it is without moral value. He thought that every action

should have pure intention behind it; otherwise, it is meaningless. The

final result is not the most important aspect of an action; rather, how

the person feels while carrying out the action is the time when value

is attached to the result.

In Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, Kant also posited the "counter-utilitarian

idea that there is a difference between preferences and values, and

that considerations of individual rights temper calculations of

aggregate utility", a concept that is an axiom in economics:

Everything has either a price or a dignity. Whatever has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; on the other hand, whatever is above all price, and therefore admits of no equivalent, has a dignity. But that which constitutes the condition under which alone something can be an end in itself does not have mere relative worth, i.e., price, but an intrinsic worth, i.e., a dignity. (p. 53, italics in original).

A phrase quoted by Kant, which is used to summarize the counter-utilitarian nature of his moral philosophy, is Fiat justitia, pereat mundus,

("Let justice be done, though the world perish"), which he translates

loosely as "Let justice reign even if all the rascals in the world

should perish from it". This appears in his 1795 Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch ("Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf"), Appendix 1.

First formulation

In his Metaphysics, Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law."

The first formulation (Formula of Universal Law) of the moral

imperative "requires that the maxims be chosen as though they should

hold as universal laws of nature" .

This formulation in principle has as its supreme law the creed "Always

act according to that maxim whose universality as a law you can at the

same time will" and is the "only condition under which a will can never

come into conflict with itself [....]"

One interpretation of the first formulation is called the "universalizability test".

An agent's maxim, according to Kant, is his "subjective principle of

human actions": that is, what the agent believes is his reason to act. The universalizability test has five steps:

- Find the agent's maxim (i.e., an action paired with its motivation). Take, for example, the declaration "I will lie for personal benefit". Lying is the action; the motivation is to fulfill some sort of desire. Together, they form the maxim.

- Imagine a possible world in which everyone in a similar position to the real-world agent followed that maxim.

- Decide if contradictions or irrationalities would arise in the possible world as a result of following the maxim.

- If a contradiction or irrationality would arise, acting on that maxim is not allowed in the real world.

- If there is no contradiction, then acting on that maxim is permissible, and is sometimes required.

Second formulation

The

second formulation (or Formula of the End in Itself) holds that "the

rational being, as by its nature an end and thus as an end in itself,

must serve in every maxim as the condition restricting all merely

relative and arbitrary ends".

The principle dictates that you "[a]ct with reference to every rational

being (whether yourself or another) so that it is an end in itself in

your maxim", meaning that the rational being is "the basis of all maxims

of action" and "must be treated never as a mere means but as the

supreme limiting condition in the use of all means, i.e., as an end at

the same time".

Third formulation

The

third formulation (i.e. Formula of Autonomy) is a synthesis of the

first two and is the basis for the "complete determination of all

maxims". It states "that all maxims which stem from autonomous

legislation ought to harmonize with a possible realm of ends as with a

realm of nature".

In principle, "So act as if your maxims should serve at the same

time as the universal law (of all rational beings)", meaning that we

should so act that we may think of ourselves as "a member in the

universal realm of ends", legislating universal laws through our maxims (that is, a universal code of conduct), in a "possible realm of ends". No one may elevate themselves above the universal law, therefore it is one's duty to follow the maxim(s).

Religion Within the Limits of Reason

Commentators,

starting in the 20th century, have tended to see Kant as having a

strained relationship with religion, though this was not the prevalent

view in the 19th century. Karl Leonhard Reinhold,

whose letters first made Kant famous, wrote "I believe that I may infer

without reservation that the interest of religion, and of Christianity

in particular, accords completely with the result of the Critique of

Reason.". Johann Schultz,

who wrote one of the first Kant commentaries, wrote "And does not this

system itself cohere most splendidly with the Christian religion? Do not

the divinity and beneficence of the latter become all the more

evident?" This view continued throughout the 19th century, as noted by Friedrich Nietzsche, who said "Kant's success is merely a theologian's success."

The reason for these views was Kant's moral theology, and the

widespread belief that his philosophy was the great antithesis to Spinozism, which had been convulsing the European academy for much of the 18th century. Spinozism was widely seen as the cause of the Pantheism controversy,

and as a form of sophisticated pantheism or even atheism. As Kant's

philosophy disregarded the possibility of arguing for God through pure

reason alone, for the same reasons it also disregarded the possibility

of arguing against God through pure reason alone. This, coupled with his

moral philosophy (his argument that the existence of morality is a

rational reason why God and an afterlife do and must exist), was the

reason he was seen by many, at least through the end of the 19th

century, as a great defender of religion in general and Christianity in

particular.

Kant articulates his strongest criticisms of the organization and

practices of religious organizations to those that encourage what he

sees as a religion of counterfeit service to God.

Among the major targets of his criticism are external ritual,

superstition and a hierarchical church order. He sees these as efforts

to make oneself pleasing to God in ways other than conscientious

adherence to the principle of moral rightness in choosing and acting

upon one's maxims. Kant's criticisms on these matters, along with his

rejection of certain theoretical proofs grounded in pure reason

(particularly the ontological argument)

for the existence of God and his philosophical commentary on some

Christian doctrines, have resulted in interpretations that see Kant as

hostile to religion in general and Christianity in particular (e.g.,

Walsh 1967). Nevertheless, other interpreters consider that Kant was

trying to mark off defensible from indefensible Christian belief. Kant sees in Jesus Christ the affirmation of a "pure moral disposition of the heart" that "can make man well-pleasing to God". Regarding Kant's conception of religion, some critics have argued that he was sympathetic to deism. Other critics have argued that Kant's moral conception moves from deism to theism (as moral theism), for example Allen W. Wood and Merold Westphal. As for Kant's book Religion within the Boundaries of bare Reason, it was emphasized that Kant reduced religiosity to rationality, religion to morality and Christianity to ethics.

Idea of freedom

In the Critique of Pure Reason,

Kant distinguishes between the transcendental idea of freedom, which as

a psychological concept is "mainly empirical" and refers to "the

question whether we must admit a power of spontaneously beginning a

series of successive things or states" as a real ground of necessity in

regard to causality,

and the practical concept of freedom as the independence of our will

from the "coercion" or "necessitation through sensuous impulses". Kant

finds it a source of difficulty that the practical idea of freedom is

founded on the transcendental idea of freedom,

but for the sake of practical interests uses the practical meaning,

taking "no account of... its transcendental meaning," which he feels was

properly "disposed of" in the Third Antinomy, and as an element in the

question of the freedom of the will is for philosophy "a real

stumbling-block" that has "embarrassed speculative reason".

Kant calls practical "everything that is possible through

freedom", and the pure practical laws that are never given through

sensuous conditions but are held analogously with the universal law of

causality are moral laws. Reason can give us only the "pragmatic laws of

free action through the senses", but pure practical laws given by

reason a priori dictate "what ought to be done".

Categories of freedom

In the Critique of Practical Reason, at the end of the second Main Part of the Analytics,

Kant introduces the categories of freedom, in analogy with the

categories of understanding their practical counterparts. Kant's

categories of freedom apparently function primarily as conditions for

the possibility for actions (i) to be free, (ii) to be understood as

free and (iii) to be morally evaluated. For Kant, although actions as

theoretical objects are constituted by means of the theoretical

categories, actions as practical objects (objects of practical use of

reason, and which can be good or bad) are constituted by means of the

categories of freedom. Only in this way can actions, as phenomena, be a

consequence of freedom, and be understood and evaluated as such.

Aesthetic philosophy

Kant discusses the subjective nature of aesthetic qualities and experiences in Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764). Kant's contribution to aesthetic theory is developed in the Critique of Judgment

(1790) where he investigates the possibility and logical status of

"judgments of taste." In the "Critique of Aesthetic Judgment," the first

major division of the Critique of Judgment, Kant used the term "aesthetic" in a manner that, according to Kant scholar W.H. Walsh, differs from its modern sense. In the Critique of Pure Reason,

to note essential differences between judgments of taste, moral

judgments, and scientific judgments, Kant abandoned the term "aesthetic"

as "designating the critique of taste," noting that judgments of taste

could never be "directed" by "laws a priori." After A. G. Baumgarten, who wrote Aesthetica (1750–58),

Kant was one of the first philosophers to develop and integrate

aesthetic theory into a unified and comprehensive philosophical system,

utilizing ideas that played an integral role throughout his philosophy.

In the chapter "Analytic of the Beautiful" in the Critique of Judgment,

Kant states that beauty is not a property of an artwork or natural

phenomenon, but is instead consciousness of the pleasure that attends

the 'free play' of the imagination and the understanding. Even though it

appears that we are using reason to decide what is beautiful, the

judgment is not a cognitive judgment,

"and is consequently not logical, but aesthetical" (§ 1). A pure

judgement of taste is subjective since it refers to the emotional

response of the subject and is based upon nothing but esteem for an

object itself: it is a disinterested pleasure, and we feel that pure

judgements of taste (i.e. judgements of beauty), lay claim to universal

validity (§§ 20–22). It is important to note that this universal

validity is not derived from a determinate concept of beauty but from common sense

(§40). Kant also believed that a judgement of taste shares

characteristics engaged in a moral judgement: both are disinterested,

and we hold them to be universal. In the chapter "Analytic of the

Sublime" Kant identifies the sublime as an aesthetic quality that, like

beauty, is subjective, but unlike beauty refers to an indeterminate

relationship between the faculties of the imagination and of reason, and

shares the character of moral judgments in the use of reason. The

feeling of the sublime, divided into two distinct modes (the

mathematical and the dynamical sublime), describes two subjective

moments that concern the relationship of the faculty of the imagination

to reason. Some commentators

argue that Kant's critical philosophy contains a third kind of the

sublime, the moral sublime, which is the aesthetic response to the moral

law or a representation, and a development of the "noble" sublime in

Kant's theory of 1764. The mathematical sublime results from the failure

of the imagination to comprehend natural objects that appear boundless

and formless, or appear "absolutely great" (§§ 23–25). This imaginative

failure is then recuperated through the pleasure taken in reason's

assertion of the concept of infinity. In this move the faculty of reason

proves itself superior to our fallible sensible self (§§ 25–26). In the

dynamical sublime there is the sense of annihilation of the sensible

self as the imagination tries to comprehend a vast might. This power of

nature threatens us but through the resistance of reason to such

sensible annihilation, the subject feels a pleasure and a sense of the

human moral vocation. This appreciation of moral feeling through

exposure to the sublime helps to develop moral character.

Kant developed a distinction between an object of art as a

material value subject to the conventions of society and the

transcendental condition of the judgment of taste as a "refined" value

in the propositions of his Idea of A Universal History (1784). In

the Fourth and Fifth Theses of that work he identified all art as the

"fruits of unsociableness" due to men's "antagonism in society"

and, in the Seventh Thesis, asserted that while such material property

is indicative of a civilized state, only the ideal of morality and the

universalization of refined value through the improvement of the mind

"belongs to culture".

Political philosophy

In Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,

Kant listed several conditions that he thought necessary for ending

wars and creating a lasting peace. They included a world of

constitutional republics. His classical republican theory was extended in the Science of Right, the first part of the Metaphysics of Morals (1797). Kant believed that universal history

leads to the ultimate world of republican states at peace, but his

theory was not pragmatic. The process was described in "Perpetual Peace"

as natural rather than rational:

The guarantee of perpetual peace is nothing less than that great artist, nature...In her mechanical course we see that her aim is to produce a harmony among men, against their will, and indeed through their discord. As a necessity working according to laws we do not know, we call it destiny. But, considering its designs in universal history, we call it "providence," inasmuch as we discern in it the profound wisdom of a higher cause which predetermines the course of nature and directs it to the objective final end of the human race.

Kant's political thought can be summarized as republican government

and international organization. "In more characteristically Kantian

terms, it is doctrine of the state based upon the law (Rechtsstaat)

and of eternal peace. Indeed, in each of these formulations, both terms

express the same idea: that of legal constitution or of 'peace through

law'. Kant's political philosophy, being essentially a legal doctrine,

rejects by definition the opposition between moral education and the

play of passions as alternate foundations for social life. The state is

defined as the union of men under law. The state is constituted by laws

which are necessary a priori because they flow from the very concept of

law. "A regime can be judged by no other criteria nor be assigned any

other functions, than those proper to the lawful order as such."

He opposed "democracy," which at his time meant direct democracy,

believing that majority rule posed a threat to individual liberty. He

stated, "...democracy is, properly speaking, necessarily a despotism,

because it establishes an executive power in which 'all' decide for or

even against one who does not agree; that is, 'all,' who are not quite

all, decide, and this is a contradiction of the general will with itself

and with freedom." As with most writers at the time, he distinguished three forms of government i.e. democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy with mixed government as the most ideal form of it.

Anthropology

5 DM 1974 D silver coin commemorating the 250th birthday of Immanuel Kant in Königsberg

Kant lectured on anthropology for over 25 years. His Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View was published in 1798. (This was the subject of Michel Foucault's secondary dissertation for his State doctorate, Introduction to Kant's Anthropology.) Kant's Lectures on Anthropology were published for the first time in 1997 in German. Introduction to Kant's Anthropology was translated into English and published by the Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy series in 2006.

Kant was among the first people of his time to introduce

anthropology as an intellectual area of study long before the field

gained popularity. As a result, his texts are considered to have

advanced the field. Kant's point of view also influenced the works of

philosophers after him such as Martin Heidegger, Paul Ricoeur, and Jean

Greisch.

Kant viewed anthropology in two broad categories. One category

was the physiological approach which he referred to as "what nature

makes of the human being". The other category was the pragmatic approach

which explored the things a human "can and should make of himself".

Influence

Kant's influence on Western thought has been profound.

Over and above his influence on specific thinkers, Kant changed the

framework within which philosophical inquiry has been carried out. He

accomplished a paradigm shift;

very little philosophy is now carried out in the style of pre-Kantian

philosophy. This shift consists in several closely related innovations

that have become foundational in philosophy itself and in the social

sciences and humanities generally:

- Kant's "Copernican revolution", that placed the role of the human subject or knower at the center of inquiry into our knowledge, such that it is impossible to philosophize about things as they are independently of us or of how they are for us;

- His invention of critical philosophy, that is of the notion of being able to discover and systematically explore possible inherent limits to our ability to know through philosophical reasoning;

- The notion of the "categorical imperative," an assertion that people are naturally endowed with the ability and obligation toward right reason and acting;

- His creation of the concept of "conditions of possibility", as in his notion of "the conditions of possible experience" – that is that things, knowledge, and forms of consciousness rest on prior conditions that make them possible, so that, to understand or to know them, we must first understand these conditions;

- The theory that objective experience is actively constituted or constructed by the functioning of the human mind;

- His notion of moral autonomy as central to humanity;

- His assertion of the principle that human beings should be treated as ends rather than as means.

Kant's ideas have been incorporated into a variety of schools of thought. These include German Idealism, Marxism, positivism, phenomenology, existentialism, critical theory, linguistic philosophy, structuralism, post-structuralism, and deconstructionism.

Historical influence

During his own life, there was much critical attention paid to his thought. He had an influence on Reinhold, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, and Novalis during the 1780s and 1790s. The school of thinking known as German Idealism

developed from his writings. The German Idealists Fichte and Schelling,

for example, tried to bring traditional "metaphysically" laden notions

like "the Absolute", "God", and "Being" into the scope of Kant's critical thought. In so doing, the German Idealists tried to reverse Kant's view that we cannot know what we cannot observe.

Statue of Immanuel Kant in Kaliningrad (Königsberg), Russia. Replica by Harald Haacke of the original by Christian Daniel Rauch lost in 1945.

Hegel was one of Kant's first major critics. In response to what he

saw as Kant's abstract and formal account, Hegel brought about an ethic

focused on the "ethical life" of the community. But Hegel's notion of "ethical life" is meant to subsume, rather than replace, Kantian ethics.

And Hegel can be seen as trying to defend Kant's idea of freedom as

going beyond finite "desires", by means of reason. Thus, in contrast to

later critics like Nietzsche or Russell, Hegel shares some of Kant's

most basic concerns.

Kant's thinking on religion was used in Britain to challenge the

decline in religious faith in the nineteenth century. British Catholic

writers, notably G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc, followed this approach. Ronald Englefield debated this movement, and Kant's use of language. Criticisms of Kant were common in the realist views of the new positivism at that time.

Arthur Schopenhauer was strongly influenced by Kant's transcendental idealism. He, like G.E. Schulze, Jacobi,

and Fichte before him, was critical of Kant's theory of the thing in

itself. Things in themselves, they argued, are neither the cause of what

we observe nor are they completely beyond our access. Ever since the

first Critique of Pure Reason philosophers have been critical of

Kant's theory of the thing in itself. Many have argued, if such a thing

exists beyond experience then one cannot posit that it affects us

causally, since that would entail stretching the category 'causality'

beyond the realm of experience.

For Schopenhauer things in themselves do not exist outside the

non-rational will. The world, as Schopenhauer would have it, is the

striving and largely unconscious will. Michael Kelly, in the preface to

his 1910 book Kant's Ethics and Schopenhauer's Criticism, stated:

"Of Kant it may be said that what is good and true in his philosophy

would have been buried with him, were it not for Schopenhauer...."

With the success and wide influence of Hegel's writings, Kant's

influence began to wane, though there was in Germany a movement that

hailed a return to Kant in the 1860s, beginning with the publication of Kant und die Epigonen in 1865 by Otto Liebmann. His motto was "Back to Kant", and a re-examination of his ideas began. During the turn of the 20th century there was an important revival of Kant's theoretical philosophy, known as the Marburg School, represented in the work of Hermann Cohen, Paul Natorp, Ernst Cassirer, and anti-Neo-Kantian Nicolai Hartmann.

Kant's notion of "Critique" has been quite influential. The Early German Romantics, especially Friedrich Schlegel in his "Athenaeum Fragments", used Kant's self-reflexive conception of criticism in their Romantic theory of poetry. Also in Aesthetics, Clement Greenberg,

in his classic essay "Modernist Painting", uses Kantian criticism, what

Greenberg refers to as "immanent criticism", to justify the aims of Abstract painting, a movement Greenberg saw as aware of the key limitiaton—flatness—that makes up the medium of painting. French philosopher Michel Foucault

was also greatly influenced by Kant's notion of "Critique" and wrote

several pieces on Kant for a re-thinking of the Enlightenment as a form

of "critical thought". He went so far as to classify his own philosophy

as a "critical history of modernity, rooted in Kant".

Kant believed that mathematical truths were forms of synthetic a priori knowledge, which means they are necessary and universal, yet known through intuition. Kant's often brief remarks about mathematics influenced the mathematical school known as intuitionism, a movement in philosophy of mathematics opposed to Hilbert's formalism, and Frege and Bertrand Russell's logicism.

Influence on modern thinkers

West German postage stamp, 1974, commemorating the 250th anniversary of Kant's birth

With his Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch, Kant is considered to have foreshadowed many of the ideas that have come to form the democratic peace theory, one of the main controversies in political science.

Prominent recent Kantians include the British philosophers P.F. Strawson, Onora O'Neill, and Quassim Cassam and the American philosophers Wilfrid Sellars and Christine Korsgaard.

Due to the influence of Strawson and Sellars, among others, there has

been a renewed interest in Kant's view of the mind. Central to many

debates in philosophy of psychology and cognitive science is Kant's conception of the unity of consciousness.

Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls are two significant political and moral philosophers whose work is strongly influenced by Kant's moral philosophy. They argued against relativism,

supporting the Kantian view that universality is essential to any

viable moral philosophy. Jean-Francois Lyotard, however, emphasized the

indeterminacy in the nature of thought and language and has engaged in

debates with Habermas based on the effects this indeterminacy has on

philosophical and political debates.

Kant's influence also has extended to the social, behavioral, and physical sciences, as in the sociology of Max Weber, the psychology of Jean Piaget, and the linguistics of Noam Chomsky. Kant's work on mathematics and synthetic a priori knowledge is also cited by theoretical physicist Albert Einstein as an early influence on his intellectual development.

Because of the thoroughness of the Kantian paradigm shift, his

influence extends to thinkers who neither specifically refer to his work

nor use his terminology.

Personal legacy

Kant

always cut a curious figure in his lifetime for his modest, rigorously

scheduled habits, which have been referred to as clocklike. But Heinrich Heine

noted the magnitude of "his destructive, world-crushing thoughts" and

considered him a sort of philosophical "executioner", comparing him to Robespierre

with the observation that both men "represented in the highest the type

of provincial bourgeois. Nature had destined them to weigh coffee and

sugar, but Fate determined that they should weigh other things and

placed on the scales of the one a king, on the scales of the other a

god."

When his body was transferred to a new burial spot, his skull was

measured during the exhumation and found to be larger than the average

German male's with a "high and broad" forehead.

His forehead has been an object of interest ever since it became

well-known through his portraits: "In Döbler's portrait and in Kiefer's

faithful if expressionistic reproduction of it — as well as in many of

the other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century portraits of

Kant — the forehead is remarkably large and decidedly retreating. Was

Kant's forehead shaped this way in these images because he was a

philosopher, or, to follow the implications of Lavater's system, was he a

philosopher because of the intellectual acuity manifested by his

forehead? Kant and Johann Kaspar Lavater were correspondents on

theological matters, and Lavater refers to Kant in his work

"Physiognomic Fragments, for the Education of Human Knowledge and Love

of People" (Leipzig & Winterthur, 1775–1778).

Tomb and statue

Kant's tomb in Kaliningrad, Russia

Kant's mausoleum adjoins the northeast corner of Königsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad, Russia. The mausoleum was constructed by the architect Friedrich Lahrs

and was finished in 1924 in time for the bicentenary of Kant's birth.

Originally, Kant was buried inside the cathedral, but in 1880 his

remains were moved to a neo-Gothic

chapel adjoining the northeast corner of the cathedral. Over the years,

the chapel became dilapidated and was demolished to make way for the

mausoleum, which was built on the same location.

The tomb and its mausoleum are among the few artifacts of German times preserved by the Soviets after they conquered and annexed the city. Today, many newlyweds bring flowers to the mausoleum.

Artifacts previously owned by Kant, known as Kantiana, were included in the Königsberg City Museum. However, the museum was destroyed during World War II.

A replica of the statue of Kant that stood in German times in front of the main University of Königsberg building was donated by a German entity in the early 1990s and placed in the same grounds.

After the expulsion of Königsberg's German population at the end of World War II,

the University of Königsberg where Kant taught was replaced by the

Russian-language Kaliningrad State University, which appropriated the

campus and surviving buildings. In 2005, the university was renamed Immanuel Kant State University of Russia. The name change was announced at a ceremony attended by President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of Germany, and the university formed a Kant Society, dedicated to the study of Kantianism.

In the late November 2018, his tomb and statue were vandalized

with paint by unknown assailants, who also scattered leaflets glorifying

Rus' and denouncing Kant as a "traitor". The incident is apparently connected with a recent vote to rename Khrabrovo Airport, where Kant was in the lead for a while, prompting nationalist resentment.

Bibliography

List of major works

- (1749) Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces (Gedanken von der wahren Schätzung der lebendigen Kräfte)

- (March 1755) Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels)

- (April 1755) Brief Outline of Certain Meditations on Fire (Meditationum quarundam de igne succinta delineatio (master's thesis under Johann Gottfried Teske))

- (September 1755) A New Elucidation of the First Principles of Metaphysical Cognition (Principiorum primorum cognitionis metaphysicae nova dilucidatio (doctoral thesis))

- (1756) The Use in Natural Philosophy of Metaphysics Combined with Geometry, Part I: Physical Monadology (Metaphysicae cum geometrica iunctae usus in philosophin naturali, cuius specimen I. continet monadologiam physicam, abbreviated as Monadologia Physica (thesis as a prerequisite of associate professorship))

- (1762) The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures (Die falsche Spitzfindigkeit der vier syllogistischen Figuren)

- (1763) The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God (Der einzig mögliche Beweisgrund zu einer Demonstration des Daseins Gottes)

- (1763) Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy (Versuch den Begriff der negativen Größen in die Weltweisheit einzuführen)

- (1764) Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (Beobachtungen über das Gefühl des Schönen und Erhabenen)

- (1764) Essay on the Illness of the Head (Über die Krankheit des Kopfes)

- (1764) Inquiry Concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality (the Prize Essay) (Untersuchungen über die Deutlichkeit der Grundsätze der natürlichen Theologie und der Moral)

- (1766) Dreams of a Spirit-Seer (Träume eines Geistersehers)

- (1768) On the Ultimate Ground of the Differentiation of Regions in Space (Von dem ersten Grunde des Unterschiedes der Gegenden im Raume)

- (August 1770) Dissertation on the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World (De mundi sensibilis atque intelligibilis forma et principiis (doctoral thesis))

- (1775) On the Different Races of Man (Über die verschiedenen Rassen der Menschen)

- (1781) First edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (Kritik der reinen Vernunft)

- (1783) Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics (Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik)

- (1784) "An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment?" ("Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?")

- (1784) "Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose" ("Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlicher Absicht")

- (1785) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten)

- (1786) Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft)

- (1786) "What does it mean to orient oneself in thinking?" ("Was heißt: sich im Denken orientieren?")

- (1786) Conjectural Beginning of Human History (Mutmaßlicher Anfang der Menschengeschichte)

- (1787) Second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason (Kritik der reinen Vernunft)

- (1788) Critique of Practical Reason (Kritik der praktischen Vernunft)

- (1790) Critique of Judgment (Kritik der Urteilskraft)

- (1793) Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone (Die Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft)

- (1793) On the Old Saw: That May be Right in Theory But It Won't Work in Practice (Über den Gemeinspruch: Das mag in der Theorie richtig sein, taugt aber nicht für die Praxis)

- (1795) Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch[180] ("Zum ewigen Frieden")

- (1797) Metaphysics of Morals (Metaphysik der Sitten). First part is The Doctrine of Right, which has often been published separately as The Science of Right.

- (1798) Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht)

- (1798) The Contest of Faculties (Der Streit der Fakultäten)

- (1800) Logic (Logik)

- (1803) On Pedagogy (Über Pädagogik)

- (1804) Opus Postumum

- (1817) Lectures on Philosophical Theology (Immanuel Kants Vorlesungen über die philosophische Religionslehre edited by K.H.L. Pölitz) [The English edition of A.W. Wood & G.M. Clark (Cornell, 1978) is based on Pölitz' second edition, 1830, of these lectures.]

Collected works in German

Wilhelm Dilthey inaugurated the Academy edition (the Akademie-Ausgabe abbreviated as AA or Ak) of Kant's writings (Gesammelte Schriften, Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin, 1902–38) in 1895, and served as its first editor. The volumes are grouped into four sections:

- I. Kant's published writings (vols. 1–9),

- II. Kant's correspondence (vols. 10–13),

- III. Kant's literary remains, or Nachlass (vols. 14–23), and

- IV. Student notes from Kant's lectures (vols. 24–29).