Stratospheric sulfur aerosols are sulfur-rich particles which exist in the stratosphere region of the Earth's atmosphere.

The layer of the atmosphere in which they exist is known as the Junge

layer, or simply the stratospheric aerosol layer. These particles

consist of a mixture of sulfuric acid and water. They are created naturally, such as by photochemical decomposition of sulfur-containing gases, e.g. carbonyl sulfide. When present in high levels, e.g. after a strong volcanic eruption such as Mount Pinatubo, they produce a cooling effect, by reflecting sunlight, and by modifying clouds as they fall out of the stratosphere. This cooling may persist for a few years before the particles fall out.

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in a gas. The sulfate particles or sulfuric acid droplets in the atmosphere are about 0.1 to 1.0 micrometer (a millionth of a meter) in diameter.

Sulfur aerosols are common in the troposphere as a result of pollution with sulfur dioxide from burning coal, and from natural processes. Volcanos are a major source of particles in the stratosphere as the force of the volcanic eruption propels sulfur-containing gases into the stratosphere. The relative influence of volcanoes on the Junge layer varies considerably according to the number and size of eruptions in any given time period, and also of quantities of sulfur compounds released. Only stratovolcanoes containing primarily granitic rocks are responsible for these fluxes, as basaltic rock erupted in shield volcanoes doesn't result in plumes which reach the stratosphere.

Creating stratospheric sulfur aerosols deliberately is a proposed geoengineering technique which offers a possible solution to some of the problems caused by global warming. However, this will not be without side effects and it has been suggested that the cure may be worse than the disease.

An aerosol is a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in a gas. The sulfate particles or sulfuric acid droplets in the atmosphere are about 0.1 to 1.0 micrometer (a millionth of a meter) in diameter.

Sulfur aerosols are common in the troposphere as a result of pollution with sulfur dioxide from burning coal, and from natural processes. Volcanos are a major source of particles in the stratosphere as the force of the volcanic eruption propels sulfur-containing gases into the stratosphere. The relative influence of volcanoes on the Junge layer varies considerably according to the number and size of eruptions in any given time period, and also of quantities of sulfur compounds released. Only stratovolcanoes containing primarily granitic rocks are responsible for these fluxes, as basaltic rock erupted in shield volcanoes doesn't result in plumes which reach the stratosphere.

Creating stratospheric sulfur aerosols deliberately is a proposed geoengineering technique which offers a possible solution to some of the problems caused by global warming. However, this will not be without side effects and it has been suggested that the cure may be worse than the disease.

Pinatubo

eruption cloud. This volcano released huge quantities of stratospheric

sulfur aerosols and contributed greatly to understanding of the subject.

Origins

Volcanic "injection"

Natural sulfur aerosols are formed in vast quantities from the SO2 ejected by volcanoes, which may be injected directly into the stratosphere during very large (Volcanic Explosivity Index, VEI, of 4 or greater) eruptions. A comprehensive analysis, dealing largely with tropospheric sulfur compounds in the atmosphere, is provided by Bates et al.

The IPCC AR4 says explosive volcanic events are episodic, but

the stratospheric aerosols resulting from them yield substantial

transitory perturbations to the radiative energy balance of the planet,

with both shortwave and longwave effects sensitive to the microphysical

characteristics of the aerosols.

During periods lacking volcanic activity (and thus direct injection of SO2 into the stratosphere), oxidation of COS (carbonyl sulfide) dominates the production of stratospheric sulfur aerosol.

Chemistry

The chemistry of stratospheric sulfur aerosols varies significantly

according to their source. Volcanic emissions vary significantly in

composition, and have complex chemistry due to the presence of ash

particulates and a wide variety of other elements in the plume.

The chemical reactions affecting both the formation and

elimination of sulfur aerosols are not fully understood. It is

difficult to estimate accurately, for example, whether the presence of

ash and water vapour is important for aerosol formation from volcanic

products, and whether high or low atmospheric concentrations of

precursor chemicals (such as SO2 and H2S) are

optimal for aerosol formation. This uncertainty makes it difficult to

determine a viable approach for geoengineering uses of sulfur aerosol

formation.

Scientific study

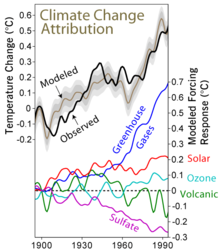

Stratospheric

sulfates from volcanic emissions cause transient cooling; the purple

line showing sustained cooling is from tropospheric sulfate

Understanding of these aerosols comes in large part from the study of volcanic eruptions, notably Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, which erupted in 1991 when scientific techniques were sufficiently far advanced to study the effects carefully.

The formation of the aerosols and their effects on the atmosphere

can also be studied in the lab. Samples of actual particles can be

recovered from the stratosphere using balloons or aircraft.

Computer models can be used to understand the behavior of

aerosol particles, and are particularly useful in modelling their effect

on global climate.

Biological experiments in the lab, and field/ocean measurements

can establish the formation mechanisms of biologically derived volatile

sulfurous gases.

Effects

It has

been established that emission of precursor gases for sulfur aerosols is

the principal mechanism by which volcanoes cause episodic global cooling. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change AR4 regards stratospheric sulfate aerosols as having a low level of scientific understanding. The aerosol particles form a whitish haze in the sky. This creates a global dimming effect, where less of the sun's radiation is able to reach the surface of the Earth. This leads to a global cooling effect. In essence, they act as the reverse of a greenhouse gas, which tends to allow visible light from the sun through, whilst blocking infrared light

emitted from the Earth's surface and its atmosphere. The particles also

radiate infrared energy directly, as they lose heat into space.

Solar radiation reduction due to volcanic eruptions

All aerosols both absorb and scatter solar and terrestrial radiation. This is quantified in the Single Scattering Albedo (SSA), the ratio of scattering alone to scattering plus absorption (extinction)

of radiation by a particle. The SSA tends to unity if scattering

dominates, with relatively little absorption, and decreases as

absorption increases, becoming zero for infinite absorption. For

example, sea-salt aerosol has an SSA of 1, as a sea-salt particle only

scatters, whereas soot has an SSA of 0.23, showing that it is a major

atmospheric aerosol absorber.

Aerosols, natural and anthropogenic, can affect the climate by changing the way radiation

is transmitted through the atmosphere. Direct observations of the

effects of aerosols are quite limited so any attempt to estimate their

global effect necessarily involves the use of computer models. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, says: While the radiative forcing due to greenhouse gases

may be determined to a reasonably high degree of accuracy... the

uncertainties relating to aerosol radiative forcings remain large, and

rely to a large extent on the estimates from global modelling studies

that are difficult to verify at the present time. However, they are mostly talking about tropospheric aerosol.

The aerosols have a role in the destruction of ozone due to surface chemistry effects. Destruction of ozone has in recent years created large holes in the ozone layer, initially over the Antarctic and then the Arctic.

These holes in the ozone layer have the potential to expand to cover

inhabited and vegetative regions of the planet, leading to catastrophic

environmental damage.

Ozone destruction occurs principally in polar regions, but the formation of ozone occurs principally in the tropics. Ozone is distributed around the planet by the Brewer-Dobson circulation. Therefore, the source and dispersal pattern of aerosols is critical in understanding their effect on the ozone layer.

Turner was inspired by dramatic sunsets caused by volcanic aerosols

Aerosols scatter light, which affects the appearance of the sky and of sunsets. Changing the concentration of aerosols in the atmosphere can dramatically affect the appearance of sunsets. A change in sky appearance during 1816, "The Year Without A Summer" (attributed to the eruption of Mount Tambora), was the inspiration for the paintings of J. M. W. Turner. Further volcanic eruptions and geoengineering projects involving sulfur aerosols are likely to affect the appearance of sunsets significantly, and to create a haze in the sky.

Aerosol particles are eventually deposited from the stratosphere

onto land and ocean. Depending on the volume of particles descending,

the effects may be significant to ecosystems, or may not be. Modelling

of the quantities of aerosols used in likely geoengineering scenarios

suggest that effects on terrestrial ecosystems from deposition is not

likely to be significantly harmful.

Climate engineering

The ability of stratospheric sulfur aerosols to create this global dimming effect has made them a possible candidate for use in climate engineering projects to limit the effect and impact of climate change due to rising levels of greenhouse gases. Delivery of precursor gases such as H2S and SO2 by artillery, aircraft and balloons has been proposed.

Understanding of this proposed technique is partly based on the

fact that it is the adaptation of an existing atmospheric process.

The technique is therefore potentially better understood than are

comparable (but purely speculative) climate engineering proposals. It is

also partly based on the speed of action of any such solution deployed, in contrast to carbon sequestration projects such as carbon dioxide air capture which would take longer to work.

However, gaps in understanding of these processes exist, for example

the effect on stratospheric climate and on rainfall patterns, and further research is needed.