| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative name | sulphur (British spelling) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | lemon yellow sintered microcrystals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight (Ar, standard) | [32.059, 32.076] conventional: 32.06 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sulfur in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | reactive nonmetal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 388.36 K (115.21 °C, 239.38 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 717.8 K (444.6 °C, 832.3 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | alpha: 2.07 g/cm3 beta: 1.96 g/cm3 gamma: 1.92 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.819 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 1314 K, 20.7 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | mono: 1.727 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | mono: 45 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 22.75 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.58 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 105±3 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 180 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of sulfur | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | orthorhombic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.205 W/(m·K) (amorphous) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 2×1015 Ω·m (at 20 °C) (amorphous) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | (α) −15.5·10−6 cm3/mol (298 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 7.7 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7704-34-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Chinese (before 2000 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as an element by | Antoine Lavoisier (1777) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of sulfur | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sulfur or sulphur is a chemical element with symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent, and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula S8. Elemental sulfur is a bright yellow, crystalline solid at room temperature.

Sulfur is the tenth most common element by mass in the universe, and the fifth most common on Earth. Though sometimes found in pure, native form, sulfur on Earth usually occurs as sulfide and sulfate minerals. Being abundant in native form, sulfur was known in ancient times, being mentioned for its uses in ancient India, ancient Greece, China, and Egypt. In the Bible, sulfur is called brimstone. Today, almost all elemental sulfur is produced as a byproduct of removing sulfur-containing contaminants from natural gas and petroleum. The greatest commercial use of the element is the production of sulfuric acid for sulfate and phosphate fertilizers, and other chemical processes. The element sulfur is used in matches, insecticides, and fungicides. Many sulfur compounds are odoriferous, and the smells of odorized natural gas, skunk scent, grapefruit, and garlic are due to organosulfur compounds. Hydrogen sulfide gives the characteristic odor to rotting eggs and other biological processes.

Sulfur is an essential element for all life, but almost always in the form of organosulfur compounds or metal sulfides. Three amino acids (cysteine, cystine, and methionine) and two vitamins (biotin and thiamine) are organosulfur compounds. Many cofactors also contain sulfur including glutathione and thioredoxin and iron–sulfur proteins. Disulfides, S–S bonds, confer mechanical strength and insolubility of the protein keratin, found in outer skin, hair, and feathers. Sulfur is one of the core chemical elements needed for biochemical functioning and is an elemental macronutrient for all living organisms.

Characteristics

When burned, sulfur melts to a blood-red liquid and emits a blue flame that is best observed in the dark.

Physical properties

Sulfur forms polyatomic molecules with different chemical formulas, the best-known allotrope being octasulfur, cyclo-S8. The point group of cyclo-S8 is D4d and its dipole moment is 0 D. Octasulfur is a soft, bright-yellow solid that is odorless, but impure samples have an odor similar to that of matches. It melts at 115.21 °C (239.38 °F), boils at 444.6 °C (832.3 °F) and sublimes easily. At 95.2 °C (203.4 °F), below its melting temperature, cyclo-octasulfur changes from α-octasulfur to the β-polymorph. The structure of the S8

ring is virtually unchanged by this phase change, which affects the

intermolecular interactions. Between its melting and boiling

temperatures, octasulfur changes its allotrope again, turning from

β-octasulfur to γ-sulfur, again accompanied by a lower density but

increased viscosity due to the formation of polymers.

At higher temperatures, the viscosity decreases as depolymerization

occurs. Molten sulfur assumes a dark red color above 200 °C (392 °F).

The density of sulfur is about 2 g/cm3, depending on the allotrope; all of the stable allotropes are excellent electrical insulators.

Chemical properties

Sulfur burns with a blue flame with formation of sulfur dioxide, which has a suffocating and irritating odor. Sulfur is insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulfide and, to a lesser extent, in other nonpolar organic solvents, such as benzene and toluene.

The first and second ionization energies of sulfur are 999.6 and

2252 kJ/mol, respectively. Despite such figures, the +2 oxidation state

is rare, with +4 and +6 being more common. The fourth and sixth

ionization energies are 4556 and 8495.8 kJ/mol, the magnitude of the

figures caused by electron transfer between orbitals; these states are

only stable with strong oxidants such as fluorine, oxygen, and chlorine.

Sulfur reacts with nearly all other elements with the exception of the noble gases, even with the notoriously unreactive metal iridium (yielding iridium disulfide). Some of those reactions need elevated temperatures.

Allotropes

The structure of the cyclooctasulfur molecule, S8

Sulfur forms over 30 solid allotropes, more than any other element. Besides S8, several other rings are known. Removing one atom from the crown gives S7, which is more of a deep yellow than the S8. HPLC analysis of "elemental sulfur" reveals an equilibrium mixture of mainly S8, but with S7 and small amounts of S6. Larger rings have been prepared, including S12 and S18.

Amorphous or "plastic" sulfur is produced by rapid cooling of molten sulfur—for example, by pouring it into cold water. X-ray crystallography studies show that the amorphous form may have a helical structure with eight atoms per turn. The long coiled polymeric molecules make the brownish substance elastic, and in bulk this form has the feel of crude rubber. This form is metastable

at room temperature and gradually reverts to crystalline molecular

allotrope, which is no longer elastic. This process happens within a

matter of hours to days, but can be rapidly catalyzed.

Isotopes

Sulfur has 25 known isotopes, four of which are stable: 32S (94.99%±0.26%), 33S (0.75%±0.02%), 34S (4.25%±0.24%), and 36S (0.01%±0.01%). Other than 35S, with a half-life of 87 days and formed in cosmic ray spallation of 40Ar, the radioactive isotopes of sulfur have half-lives less than 3 hours.

When sulfide minerals

are precipitated, isotopic equilibration among solids and liquid may

cause small differences in the δS-34 values of co-genetic minerals. The

differences between minerals can be used to estimate the temperature of

equilibration. The δC-13 and δS-34 of coexisting carbonate minerals and sulfides can be used to determine the pH and oxygen fugacity of the ore-bearing fluid during ore formation.

In most forest

ecosystems, sulfate is derived mostly from the atmosphere; weathering

of ore minerals and evaporites contribute some sulfur. Sulfur with a

distinctive isotopic composition has been used to identify pollution

sources, and enriched sulfur has been added as a tracer in hydrologic studies. Differences in the natural abundances can be used in systems where there is sufficient variation in the 34S of ecosystem components. Rocky Mountain lakes thought to be dominated by atmospheric sources of sulfate have been found to have different δ34S values from lakes believed to be dominated by watershed sources of sulfate.

Natural occurrence

Sulfur vat from which railroad cars are loaded, Freeport Sulphur Co., Hoskins Mound, Texas (1943)

A man carrying sulfur blocks from Kawah Ijen, a volcano in East Java, Indonesia, 2009

32S is created inside massive stars, at a depth where the temperature exceeds 2.5×109 K, by the fusion of one nucleus of silicon plus one nucleus of helium. As this nuclear reaction is part of the alpha process that produces elements in abundance, sulfur is the 10th most common element in the universe.

Sulfur, usually as sulfide, is present in many types of meteorites.

Ordinary chondrites contain on average 2.1% sulfur, and carbonaceous

chondrites may contain as much as 6.6%. It is normally present as troilite (FeS), but there are exceptions, with carbonaceous chondrites containing free sulfur, sulfates and other sulfur compounds. The distinctive colors of Jupiter's volcanic moon Io are attributed to various forms of molten, solid, and gaseous sulfur.

It is the fifth most common element by mass in the Earth. Elemental sulfur can be found near hot springs and volcanic regions in many parts of the world, especially along the Pacific Ring of Fire;

such volcanic deposits are currently mined in Indonesia, Chile, and

Japan. These deposits are polycrystalline, with the largest documented

single crystal measuring 22×16×11 cm. Historically, Sicily was a major source of sulfur in the Industrial Revolution.

Native sulfur is synthesized by anaerobic bacteria acting on sulfate minerals such as gypsum in salt domes. Significant deposits in salt domes occur along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, and in evaporites

in eastern Europe and western Asia. Native sulfur may be produced by

geological processes alone. Fossil-based sulfur deposits from salt domes

were until recently the basis for commercial production in the United

States, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine.

Currently, commercial production is still carried out in the Osiek mine

in Poland. Such sources are now of secondary commercial importance, and

most are no longer worked.

Common naturally occurring sulfur compounds include the sulfide minerals, such as pyrite (iron sulfide), cinnabar (mercury sulfide), galena (lead sulfide), sphalerite (zinc sulfide) and stibnite (antimony sulfide); and the sulfates, such as gypsum (calcium sulfate), alunite (potassium aluminium sulfate), and barite

(barium sulfate). On Earth, just as upon Jupiter's moon Io, elemental

sulfur occurs naturally in volcanic emissions, including emissions from hydrothermal vents.

Compounds

Common oxidation states of sulfur range from −2 to +6. Sulfur forms stable compounds with all elements except the noble gases.

Sulfur polycations

Sulfur polycations, S82+, S42+ and S162+ are produced when sulfur is reacted with mild oxidizing agents in a strongly acidic solution. The colored solutions produced by dissolving sulfur in oleum

were first reported as early as 1804 by C.F. Bucholz, but the cause of

the color and the structure of the polycations involved was only

determined in the late 1960s. S82+ is deep blue, S42+ is yellow and S162+ is red.

Sulfides

Treatment of sulfur with hydrogen gives hydrogen sulfide. When dissolved in water, hydrogen sulfide is mildly acidic:

- H2S ⇌ HS− + H+

Hydrogen sulfide gas and the hydrosulfide anion are extremely toxic

to mammals, due to their inhibition of the oxygen-carrying capacity of

hemoglobin and certain cytochromes in a manner analogous to cyanide and azide.

Reduction of elemental sulfur gives polysulfides, which consist of chains of sulfur atoms terminated with S− centers:

- 2 Na + S8 → Na2S8

This reaction highlights a distinctive property of sulfur: its ability to catenate (bind to itself by formation of chains). Protonation of these polysulfide anions produces the polysulfanes, H2Sx where x = 2, 3, and 4. Ultimately, reduction of sulfur produces sulfide salts:

- 16 Na + S8 → 8 Na2S

The interconversion of these species is exploited in the sodium-sulfur battery.

The radical anion S3− gives the blue color of the mineral lapis lazuli.

Lapis lazuli owes its blue color to a trisulfur radical anion (S−

3)

3)

Two parallel sulfur chains grown inside a single-wall carbon nanotube (CNT, a). Zig-zag (b) and straight (c) S chains inside double-wall CNTs

Oxides, oxoacids and oxoanions

The principal sulfur oxides are obtained by burning sulfur:

- S + O2 → SO2 (sulfur dioxide)

- 2 SO2 + O2 → 2 SO3 (sulfur trioxide)

Multiple sulfur oxides are known; the sulfur-rich oxides include sulfur monoxide, disulfur monoxide, disulfur dioxides, and higher oxides containing peroxo groups.

Sulfur forms sulfur oxoacids, some of which cannot be isolated and are only known through the salts. Sulfur dioxide and sulfites (SO2−

3) are related to the unstable sulfurous acid (H2SO3). Sulfur trioxide and sulfates (SO2−

4) are related to sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Sulfuric acid and SO3 combine to give oleum, a solution of pyrosulfuric acid (H2S2O7) in sulfuric acid.

3) are related to the unstable sulfurous acid (H2SO3). Sulfur trioxide and sulfates (SO2−

4) are related to sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Sulfuric acid and SO3 combine to give oleum, a solution of pyrosulfuric acid (H2S2O7) in sulfuric acid.

Thiosulfate salts (S

2O2−

3), sometimes referred as "hyposulfites", used in photographic fixing (hypo) and as reducing agents, feature sulfur in two oxidation states. Sodium dithionite (Na

2S

2O

4), contains the more highly reducing dithionite anion (S

2O2−

4).

2O2−

3), sometimes referred as "hyposulfites", used in photographic fixing (hypo) and as reducing agents, feature sulfur in two oxidation states. Sodium dithionite (Na

2S

2O

4), contains the more highly reducing dithionite anion (S

2O2−

4).

Halides and oxyhalides

Several sulfur halides are important to modern industry. Sulfur hexafluoride is a dense gas used as an insulator gas in high voltage transformers; it is also a nonreactive and nontoxic propellant for pressurized containers. Sulfur tetrafluoride is a rarely used organic reagent that is highly toxic. Sulfur dichloride and disulfur dichloride are important industrial chemicals. Sulfuryl chloride and chlorosulfuric acid are derivatives of sulfuric acid; thionyl chloride (SOCl2) is a common reagent in organic synthesis.

Pnictides

An important S–N compound is the cage tetrasulfur tetranitride (S4N4). Heating this compound gives polymeric sulfur nitride ((SN)x), which has metallic properties even though it does not contain any metal atoms. Thiocyanates contain the SCN− group. Oxidation of thiocyanate gives thiocyanogen, (SCN)2 with the connectivity NCS-SCN. Phosphorus sulfides are numerous, the most important commercially being the cages P4S10 and P4S3.

Metal sulfides

The principal ores of copper, zinc, nickel, cobalt, molybdenum, and

other metals are sulfides. These materials tend to be dark-colored semiconductors that are not readily attacked by water or even many acids. They are formed, both geochemically and in the laboratory, by the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with metal salts. The mineral galena (PbS) was the first demonstrated semiconductor and was used as a signal rectifier in the cat's whiskers of early crystal radios. The iron sulfide called pyrite, the so-called "fool's gold", has the formula FeS2. Processing these ores, usually by roasting, is costly and environmentally hazardous. Sulfur corrodes many metals through tarnishing.

Organic compounds

- Illustrative organosulfur compounds

- Allicin, the active ingredient in garlic

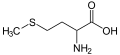

- (R)-cysteine, an amino acid containing a thiol group

- Methionine, an amino acid containing a thioether

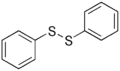

- Diphenyl disulfide, a representative disulfide

- Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, a controversial surfactant

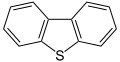

- Dibenzothiophene, a component of crude oil

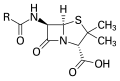

- Penicillin, an antibiotic where "R" is the variable group

Some of the main classes of sulfur-containing organic compounds include the following:

- Thiols or mercaptans (so called because they capture mercury as chelators) are the sulfur analogs of alcohols; treatment of thiols with base gives thiolate ions.

- Thioethers are the sulfur analogs of ethers.

- Sulfonium ions have three groups attached to a cationic sulfur center. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) is one such compound, important in the marine organic sulfur cycle.

- Sulfoxides and sulfones are thioethers with one and two oxygen atoms attached to the sulfur atom, respectively. The simplest sulfoxide, dimethyl sulfoxide, is a common solvent; a common sulfone is sulfolane.

- Sulfonic acids are used in many detergents.

Compounds with carbon-sulfur multiple bonds are uncommon, an exception being carbon disulfide, a volatile colorless liquid that is structurally similar to carbon dioxide. It is used as a reagent to make the polymer rayon and many organosulfur compounds. Unlike carbon monoxide, carbon monosulfide is stable only as an extremely dilute gas, found between solar systems.

Organosulfur compounds are responsible for some of the unpleasant

odors of decaying organic matter. They are widely known as the odorant

in domestic natural gas, garlic odor, and skunk spray. Not all organic

sulfur compounds smell unpleasant at all concentrations: the

sulfur-containing monoterpenoid (grapefruit mercaptan) in small concentrations is the characteristic scent of grapefruit, but has a generic thiol odor at larger concentrations. Sulfur mustard, a potent vesicant, was used in World War I as a disabling agent.

Sulfur-sulfur bonds are a structural component used to stiffen

rubber, similar to the disulfide bridges that rigidify proteins (see

biological below). In the most common type of industrial "curing" or

hardening and strengthening of natural rubber, elemental sulfur is heated with the rubber to the point that chemical reactions form disulfide bridges between isoprene

units of the polymer. This process, patented in 1843, made rubber a

major industrial product, especially in automobile tires. Because of the

heat and sulfur, the process was named vulcanization, after the Roman god of the forge and volcanism.

History

Antiquity

Pharmaceutical container for sulfur from the first half of the 20th century. From the Museo del Objeto del Objeto collection

Being abundantly available in native form, sulfur was known in ancient times and is referred to in the Torah (Genesis). English translations of the Bible commonly referred to burning sulfur as "brimstone", giving rise to the term "fire-and-brimstone" sermons, in which listeners are reminded of the fate of eternal damnation that await the unbelieving and unrepentant. It is from this part of the Bible that Hell is implied to "smell of sulfur" (likely due to its association with volcanic activity). According to the Ebers Papyrus, a sulfur ointment was used in ancient Egypt to treat granular eyelids. Sulfur was used for fumigation in preclassical Greece; this is mentioned in the Odyssey. Pliny the Elder discusses sulfur in book 35 of his Natural History, saying that its best-known source is the island of Melos. He mentions its use for fumigation, medicine, and bleaching cloth.

A natural form of sulfur known as shiliuhuang (石硫黄) was known in China since the 6th century BC and found in Hanzhong. By the 3rd century, the Chinese discovered that sulfur could be extracted from pyrite. Chinese Daoists were interested in sulfur's flammability and its reactivity with certain metals, yet its earliest practical uses were found in traditional Chinese medicine. A Song dynasty military treatise of 1044 AD described different formulas for Chinese black powder, which is a mixture of potassium nitrate (KNO

3), charcoal, and sulfur. It remains an ingredient of black gunpowder.

3), charcoal, and sulfur. It remains an ingredient of black gunpowder.

Indian alchemists, practitioners of "the science of mercury" (sanskrit

rasaśāstra, रसशास्त्र), wrote extensively about the use of sulfur in

alchemical operations with mercury, from the eighth century AD onwards. In the rasaśāstra tradition, sulfur is called "the smelly" (sanskrit gandhaka, गन्धक).

Early European alchemists gave sulfur a unique alchemical symbol,

a triangle at the top of a cross. In traditional skin treatment,

elemental sulfur was used (mainly in creams) to alleviate such

conditions as scabies, ringworm, psoriasis, eczema, and acne.

The mechanism of action is unknown—though elemental sulfur does oxidize

slowly to sulfurous acid, which is (through the action of sulfite) a mild reducing and antibacterial agent.

Modern times

Sicilian kiln used to obtain sulfur from volcanic rock

In 1777, Antoine Lavoisier helped convince the scientific community that sulfur was an element, not a compound.

Sulfur deposits in Sicily

were the dominant source for more than a century. By the late 18th

century, about 2,000 tonnes per year of sulfur were imported into Marseilles, France, for the production of sulfuric acid for use in the Leblanc process. In industrializing Britain, with the repeal of tariffs

on salt in 1824, demand for sulfur from Sicily surged upward. The

increasing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and

transportation of the sulfur, coupled with the failure of this

lucrative export to transform Sicily's backward and impoverished

economy, led to the 'Sulfur Crisis' of 1840, when King Ferdinand II

gave a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French firm, violating an

earlier 1816 trade agreement with Britain. A peaceful solution was

eventually negotiated by France.

In 1867, elemental sulfur was discovered in underground deposits in Louisiana and Texas. The highly successful Frasch process was developed to extract this resource.

In the late 18th century, furniture makers used molten sulfur to produce decorative inlays in their craft. Because of the sulfur dioxide

produced during the process of melting sulfur, the craft of sulfur

inlays was soon abandoned. Molten sulfur is sometimes still used for

setting steel bolts into drilled concrete holes where high shock

resistance is desired for floor-mounted equipment attachment points.

Pure powdered sulfur was used as a medicinal tonic and laxative. With the advent of the contact process, the majority of sulfur today is used to make sulfuric acid for a wide range of uses, particularly fertilizer.

Spelling and etymology

Sulfur is derived from the Latin word sulpur, which was Hellenized to sulphur. The spelling sulfur appears toward the end of the Classical period. (The true Greek word for sulfur, θεῖον, is the source of the international chemical prefix thio-.) In 12th-century Anglo-French, it was sulfre; in the 14th century the Latin -ph- was restored, for sulphre; and by the 15th century the full Latin spelling was restored, for sulfur, sulphur. The parallel f~ph spellings continued in Britain until the 19th century, when the word was standardized as sulphur. Sulfur was the form chosen in the United States, whereas Canada uses both. The IUPAC adopted the spelling sulfur in 1990, as did the Nomenclature Committee of the Royal Society of Chemistry in 1992, restoring the spelling sulfur to Britain. Oxford Dictionaries note that "in chemistry and other technical uses ... the -f-

spelling is now the standard form for this and related words in British

as well as US contexts, and is increasingly used in general contexts as

well."

Production

Traditional sulfur mining at Ijen Volcano,

East Java, Indonesia. This image shows the dangerous and rugged

conditions the miners face, including toxic smoke and high drops, as

well as their lack of protective equipment. The pipes over which they

are standing are for condensing sulfur vapors.

Sulfur may be found by itself and historically was usually obtained in this form; pyrite has also been a source of sulfur. In volcanic regions in Sicily, in ancient times, it was found on the surface of the Earth, and the "Sicilian process"

was used: sulfur deposits were piled and stacked in brick kilns built

on sloping hillsides, with airspaces between them. Then, some sulfur was

pulverized, spread over the stacked ore and ignited, causing the free

sulfur to melt down the hills. Eventually the surface-borne deposits

played out, and miners excavated veins that ultimately dotted the

Sicilian landscape with labyrinthine mines. Mining was unmechanized and

labor-intensive, with pickmen freeing the ore from the rock, and

mine-boys or carusi

carrying baskets of ore to the surface, often through a mile or more of

tunnels. Once the ore was at the surface, it was reduced and extracted

in smelting ovens. The conditions in Sicilian sulfur mines were

horrific, prompting Booker T. Washington

to write "I am not prepared just now to say to what extent I believe in

a physical hell in the next world, but a sulphur mine in Sicily is

about the nearest thing to hell that I expect to see in this life."

Elemental sulfur was extracted from salt domes

(in which it sometimes occurs in nearly pure form) until the late 20th

century. Sulfur is now produced as a side product of other industrial

processes such as in oil refining, in which sulfur is undesired. As a

mineral, native sulfur under salt domes is thought to be a fossil

mineral resource, produced by the action of ancient bacteria on sulfate

deposits. It was removed from such salt-dome mines mainly by the Frasch process.

In this method, superheated water was pumped into a native sulfur

deposit to melt the sulfur, and then compressed air returned the 99.5%

pure melted product to the surface. Throughout the 20th century this

procedure produced elemental sulfur that required no further

purification. Due to a limited number of such sulfur deposits and the

high cost of working them, this process for mining sulfur has not been

employed in a major way anywhere in the world since 2002.

Sulfur recovered from hydrocarbons in Alberta, stockpiled for shipment in North Vancouver, British Columbia

Today, sulfur is produced from petroleum, natural gas, and related fossil resources, from which it is obtained mainly as hydrogen sulfide. Organosulfur compounds, undesirable impurities in petroleum, may be upgraded by subjecting them to hydrodesulfurization, which cleaves the C–S bonds:

- R-S-R + 2 H2 → 2 RH + H2S

The resulting hydrogen sulfide from this process, and also as it

occurs in natural gas, is converted into elemental sulfur by the Claus process. This process entails oxidation of some hydrogen sulfide to sulfur dioxide and then the comproportionation of the two:

- 3 O2 + 2 H2S → 2 SO2 + 2 H2O

- SO2 + 2 H2S → 3 S + 2 H2O

Production and price (US market) of elemental sulfur

Owing to the high sulfur content of the Athabasca Oil Sands, stockpiles of elemental sulfur from this process now exist throughout Alberta, Canada. Another way of storing sulfur is as a binder for concrete, the resulting product having many desirable properties.

Sulfur is still mined from surface deposits in poorer nations with

volcanoes, such as Indonesia, and worker conditions have not improved

much since Booker T. Washington's days.

The world production of sulfur in 2011 amounted to 69 million

tonnes (Mt), with more than 15 countries contributing more than 1 Mt

each. Countries producing more than 5 Mt are China (9.6), US (8.8),

Canada (7.1) and Russia (7.1). Production has been slowly increasing from 1900 to 2010; the price was unstable in the 1980s and around 2010.

Applications

Sulfuric acid

Elemental sulfur is used mainly as a precursor to other chemicals. Approximately 85% (1989) is converted to sulfuric acid (H2SO4):

- 2 S + 3 O2 + 2 H2O → 2 H2SO4

- Sulfuric acid production in 2000

In 2010, the United States produced more sulfuric acid than any other inorganic industrial chemical.

The principal use for the acid is the extraction of phosphate ores for

the production of fertilizer manufacturing. Other applications of

sulfuric acid include oil refining, wastewater processing, and mineral

extraction.

Other important sulfur chemistry

Sulfur reacts directly with methane to give carbon disulfide, used to manufacture cellophane and rayon. One of the uses of elemental sulfur is in vulcanization of rubber, where polysulfide chains crosslink organic polymers. Large quantities of sulfites are used to bleach paper and to preserve dried fruit. Many surfactants and detergents (e.g. sodium lauryl sulfate) are sulfate derivatives. Calcium sulfate, gypsum, (CaSO4·2H2O) is mined on the scale of 100 million tonnes each year for use in Portland cement and fertilizers.

When silver-based photography was widespread, sodium and ammonium thiosulfate were widely used as "fixing agents". Sulfur is a component of gunpowder ("black powder").

Fertilizer

Sulfur is increasingly used as a component of fertilizers. The most important form of sulfur for fertilizer is the mineral calcium sulfate. Elemental sulfur is hydrophobic

(not soluble in water) and cannot be used directly by plants. Over

time, soil bacteria can convert it to soluble derivatives, which can

then be used by plants. Sulfur improves the efficiency of other

essential plant nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus.

Biologically produced sulfur particles are naturally hydrophilic due to

a biopolymer coating and are easier to disperse over the land in a

spray of diluted slurry, resulting in a faster uptake.

The botanical requirement for sulfur equals or exceeds the requirement for phosphorus. It is an essential nutrient for plant

growth, root nodule formation of legumes, and immunity and defense

systems. Sulfur deficiency has become widespread in many countries in

Europe.

Because atmospheric inputs of sulfur continue to decrease, the deficit

in the sulfur input/output is likely to increase unless sulfur

fertilizers are used.

Fine chemicals

A molecular model of the pesticide malathion

Organosulfur compounds are used in pharmaceuticals, dyestuffs, and agrochemicals. Many drugs contain sulfur, early examples being antibacterial sulfonamides, known as sulfa drugs. Sulfur is a part of many bacterial defense molecules. Most β-lactam antibiotics, including the penicillins, cephalosporins and monolactams contain sulfur.

Magnesium sulfate, known as Epsom salts when in hydrated crystal form, can be used as a laxative, a bath additive, an exfoliant, magnesium supplement for plants, or (when in dehydrated form) as a desiccant.

Fungicide and pesticide

Sulfur candle originally sold for home fumigation

Elemental sulfur is one of the oldest fungicides and pesticides.

"Dusting sulfur", elemental sulfur in powdered form, is a common

fungicide for grapes, strawberry, many vegetables and several other

crops. It has a good efficacy against a wide range of powdery mildew

diseases as well as black spot. In organic production, sulfur is the

most important fungicide. It is the only fungicide used in organically farmed apple production against the main disease apple scab

under colder conditions. Biosulfur (biologically produced elemental

sulfur with hydrophilic characteristics) can also be used for these

applications.

Standard-formulation dusting sulfur is applied to crops with a

sulfur duster or from a dusting plane. Wettable sulfur is the commercial

name for dusting sulfur formulated with additional ingredients to make

it water miscible. It has similar applications and is used as a fungicide against mildew and other mold-related problems with plants and soil.

Elemental sulfur powder is used as an "organic" (i.e., "green") insecticide (actually an acaricide) against ticks and mites. A common method of application is dusting the clothing or limbs with sulfur powder.

A diluted solution of lime sulfur (made by combining calcium hydroxide with elemental sulfur in water) is used as a dip for pets to destroy ringworm (fungus), mange, and other dermatoses and parasites.

Sulfur candles of almost pure sulfur were burned to fumigate structures and wine barrels, but are now considered too toxic for residences.

Bactericide in winemaking and food preservation

Small amounts of sulfur dioxide gas addition (or equivalent potassium metabisulfite addition) to fermented wine to produce traces of sulfurous acid (produced when SO2 reacts with water) and its sulfite salts in the mixture, has been called "the most powerful tool in winemaking". After the yeast-fermentation stage in winemaking, sulfites absorb oxygen and inhibit aerobic

bacterial growth that otherwise would turn ethanol into acetic acid,

souring the wine. Without this preservative step, indefinite

refrigeration of the product before consumption is usually required.

Similar methods go back into antiquity but modern historical mentions of

the practice go to the fifteenth century. The practice is used by large

industrial wine producers and small organic wine producers alike.

Sulfur dioxide and various sulfites have been used for their

antioxidant antibacterial preservative properties in many other parts of

the food industry. The practice has declined since reports of an

allergy-like reaction of some persons to sulfites in foods.

Pharmaceuticals

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | Topical, rarely oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ChEBI | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.839 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | S8 |

| Molar mass | 256.52 g/mol g·mol−1 |

Sulfur (specifically octasulfur, S8) is used in pharmaceutical skin preparations for the treatment of acne and other conditions. It acts as a keratolytic agent and also kills bacteria, fungi, scabies mites and other parasites. Precipitated sulfur and colloidal sulfur are used, in form of lotions, creams, powders, soaps, and bath additives, for the treatment of acne vulgaris, acne rosacea, and seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Common adverse effects include irritation of the skin at the application site, such as dryness, stinging, itching and peeling.

Mechanism of action

Sulfur is converted to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) through reduction, partly by bacteria. H2S kills bacteria (possibly including Propionibacterium acnes which plays a role in acne,) fungi, and parasites such as scabies mites. Sulfur's keratolytic action is also mediated by H2S; in this case, the hydrogen sulfide is produced by direct interaction with the target keratinocytes themselves.

Furniture

Sulfur can be used to create decorative inlays

in wooden furniture. After a design has been cut into the wood, molten

sulfur is poured in and then scraped away so it is flush. Sulfur inlays

were particularly popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries,

notably among Pennsylvania German

cabinetmakers. The practice soon died out, as less toxic and flammable

substances were substituted. However, some modern craftsmen have

occasionally revived the technique in the creation of replica pieces.

Biological role

Protein and organic cofactors

Sulfur is an essential component of all living cells. It is either the seventh or eighth most abundant element in the human body by weight, about equal in abundance to potassium, and slightly greater than sodium and chlorine. A 70 kg (150 lb) human body contains about 140 grams of sulfur.

In plants and animals, the amino acids cysteine and methionine contain most of the sulfur, and the element is present in all polypeptides, proteins, and enzymes

that contain these amino acids. In humans, methionine is an essential

amino acid that must be ingested. However, save for the vitamins biotin and thiamine, cysteine and all sulfur-containing compounds in the human body can be synthesized from methionine. The enzyme sulfite oxidase is needed for the metabolism of methionine and cysteine in humans and animals.

Disulfide bonds

(S-S bonds) between cysteine residues in peptide chains are very

important in protein assembly and structure. These covalent bonds

between peptide chains confer extra toughness and rigidity.

For example, the high strength of feathers and hair is due in part to

the high content of S-S bonds with cysteine and sulfur. Eggs are high in

sulfur to nourish feather formation in chicks, and the characteristic

odor of rotting eggs is due to hydrogen sulfide.

The high disulfide bond content of hair and feathers contributes to

their indigestibility and to their characteristic disagreeable odor when

burned.

Homocysteine and taurine are other sulfur-containing acids that are similar in structure, but not coded by DNA, and are not part of the primary structure

of proteins. Many important cellular enzymes use prosthetic groups

ending with -SH moieties to handle reactions involving acyl-containing

biochemicals: two common examples from basic metabolism are coenzyme A and alpha-lipoic acid. Two of the 13 classical vitamins, biotin and thiamine, contain sulfur, with the latter being named for its sulfur content.

In intracellular chemistry, sulfur operates as a carrier of

reducing hydrogen and its electrons for cellular repair of oxidation.

Reduced glutathione, a sulfur-containing tripeptide, is a reducing agent through its sulfhydryl (-SH) moiety derived from cysteine. The thioredoxins,

a class of small proteins essential to all known life, use neighboring

pairs of reduced cysteines to work as general protein reducing agents,

with similar effect.

Methanogenesis, the route to most of the world's methane, is a multistep biochemical transformation of carbon dioxide. This conversion requires several organosulfur cofactors. These include coenzyme M, CH3SCH2CH2SO3−, the immediate precursor to methane.

Metalloproteins and inorganic cofactors

Inorganic sulfur forms a part of iron–sulfur clusters as well as many copper, nickel, and iron proteins. Most pervasive are the ferrodoxins, which serve as electron shuttles in cells. In bacteria, the important nitrogenase enzymes contains an Fe–Mo–S cluster and is a catalyst that performs the important function of nitrogen fixation,

converting atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia that can be used by

microorganisms and plants to make proteins, DNA, RNA, alkaloids, and the

other organic nitrogen compounds necessary for life.

Sulfur metabolism and the sulfur cycle

The sulfur cycle was the first of the biogeochemical cycles to be discovered. In the 1880s, while studying Beggiatoa (a bacterium living in a sulfur rich environment), Sergei Winogradsky found that it oxidized hydrogen sulfide (H2S)

as an energy source, forming intracellular sulfur droplets. Winogradsky

referred to this form of metabolism as inorgoxidation (oxidation of

inorganic compounds). He continued to study it together with Selman Waksman until the 1950s.

Sulfur oxidizers can use as energy sources reduced sulfur compounds, including hydrogen sulfide, elemental sulfur, sulfite, thiosulfate, and various polythionates (e.g., tetrathionate). They depend on enzymes such as sulfur oxygenase and sulfite oxidase to oxidize sulfur to sulfate. Some lithotrophs can even use the energy contained in sulfur compounds to produce sugars, a process known as chemosynthesis. Some bacteria and archaea use hydrogen sulfide in place of water as the electron donor in chemosynthesis, a process similar to photosynthesis that produces sugars and utilizes oxygen as the electron acceptor. The photosynthetic green sulfur bacteria and purple sulfur bacteria and some lithotrophs use elemental oxygen to carry out such oxidization of hydrogen sulfide to produce elemental sulfur (S0), oxidation state = 0. Primitive bacteria that live around deep ocean volcanic vents oxidize hydrogen sulfide in this way with oxygen; the giant tube worm is an example of a large organism that uses hydrogen sulfide (via bacteria) as food to be oxidized.

The so-called sulfate-reducing bacteria,

by contrast, "breathe sulfate" instead of oxygen. They use organic

compounds or molecular hydrogen as the energy source. They use sulfur as

the electron acceptor, and reduce various oxidized sulfur compounds

back into sulfide, often into hydrogen sulfide. They can grow on other

partially oxidized sulfur compounds (e.g. thiosulfates, thionates,

polysulfides, sulfites). The hydrogen sulfide produced by these bacteria

is responsible for some of the smell of intestinal gases (flatus) and decomposition products.

Sulfur is absorbed by plants roots from soil as sulfate and transported as a phosphate ester. Sulfate is reduced to sulfide via sulfite before it is incorporated into cysteine and other organosulfur compounds.

- SO42− → SO32− → H2S → cysteine → methionine

Precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS signal word | Warning |

| H315 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

Effect of acid rain on a forest, Jizera Mountains, Czech Republic

Elemental sulfur is non-toxic, as are most of the soluble sulfate salts, such as Epsom salts.

Soluble sulfate salts are poorly absorbed and laxative. When injected

parenterally, they are freely filtered by the kidneys and eliminated

with very little toxicity in multi-gram amounts.

When sulfur burns in air, it produces sulfur dioxide.

In water, this gas produces sulfurous acid and sulfites; sulfites are

antioxidants that inhibit growth of aerobic bacteria and a useful food additive in small amounts. At high concentrations these acids harm the lungs, eyes or other tissues. In organisms without lungs such as insects or plants, sulfite in high concentration prevents respiration.

Sulfur trioxide (made by catalysis from sulfur dioxide) and sulfuric acid

are similarly highly acidic and corrosive in the presence of water.

Sulfuric acid is a strong dehydrating agent that can strip available

water molecules and water components from sugar and organic tissue.

The burning of coal and/or petroleum by industry and power plants generates sulfur dioxide (SO2) that reacts with atmospheric water and oxygen to produce sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and sulfurous acid (H2SO3). These acids are components of acid rain, lowering the pH of soil and freshwater bodies, sometimes resulting in substantial damage to the environment and chemical weathering of statues and structures. Fuel standards increasingly require that fuel producers extract sulfur from fossil fuels

to prevent acid rain formation. This extracted and refined sulfur

represents a large portion of sulfur production. In coal-fired power

plants, flue gases are sometimes purified. More modern power plants that use synthesis gas extract the sulfur before they burn the gas.

Hydrogen sulfide is as toxic as hydrogen cyanide, and kills by the same mechanism (inhibition of the respiratory enzyme cytochrome oxidase),

though hydrogen sulfide is less likely to cause surprise poisonings

from small inhaled amounts because of its disagreeable odor. Hydrogen

sulfide quickly deadens the sense of smell and a victim may breathe

increasing quantities without noticing the increase until severe

symptoms cause death. Dissolved sulfide and hydrosulfide salts are toxic by the same mechanism.