An Egyptian stele thought to represent a polio victim. 18th Dynasty (1403–1365 BC).

The history of polio (poliomyelitis) infections extends into prehistory. Although major polio epidemics were unknown before the 20th century, the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Over millennia, polio survived quietly as an endemic pathogen until the 1900s when major epidemics began to occur in Europe;

soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the United States. By

1910, frequent epidemics became regular events throughout the developed

world, primarily in cities during the summer months. At its peak in the

1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyze or kill over half a million people

worldwide every year.

The fear and the collective response to these epidemics would

give rise to extraordinary public reaction and mobilization; spurring

the development of new methods to prevent and treat the disease, and

revolutionizing medical philanthropy. Although the development of two polio vaccines has eliminated poliomyelitis in all but three countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria), the legacy of poliomyelitis remains, in the development of modern rehabilitation therapy, and in the rise of disability rights movements worldwide.

Early history

Ancient Egyptian paintings and carvings depict otherwise healthy people with withered limbs, and children walking with canes at a young age. It is theorized that the Roman Emperor Claudius was stricken as a child, and this caused him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. Perhaps the earliest recorded case of poliomyelitis is that of Sir Walter Scott. In 1773 Scott was said to have developed "a severe teething fever which deprived him of the power of his right leg". At the time, polio was not known to medicine. A retrospective diagnosis of polio is considered to be strong due to the detailed account Scott later made, and the resultant lameness of his right leg had an important effect on his life and writing.

The symptoms of poliomyelitis have been described by many names.

In the early nineteenth century the disease was known variously as:

Dental Paralysis, Infantile Spinal Paralysis, Essential Paralysis of

Children, Regressive Paralysis, Myelitis of the Anterior Horns,

Tephromyelitis (from the Greek tephros, meaning "ash-gray") and Paralysis of the Morning. In 1789 the first clinical description of poliomyelitis was provided by the British physician Michael Underwood—he refers to polio as "a debility of the lower extremities". The first medical report on poliomyelitis was by Jakob Heine, in 1840; he called the disease Lähmungszustände der unteren Extremitäten ("Paralysis of the lower Extremities"). Karl Oskar Medin was the first to empirically study a poliomyelitis epidemic in 1890. This work, and the prior classification by Heine, led to the disease being known as Heine-Medin disease.

Epidemics

Major polio epidemics

were unknown before the 20th century; localized paralytic polio

epidemics began to appear in Europe and the United States around 1900. The first report of multiple polio cases was published in 1843 and described an 1841 outbreak in Louisiana. A fifty-year gap occurs before the next U.S. report—a cluster of 26 cases in Boston in 1893. The first recognized U.S. polio epidemic occurred the following year in Vermont with 132 total cases (18 deaths), including several cases in adults.

Numerous epidemics of varying magnitude began to appear throughout the

country; by 1907 approximately 2,500 cases of poliomyelitis were

reported in New York City.

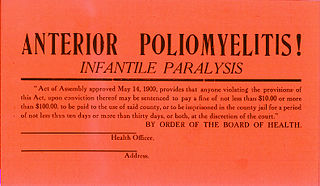

This

cardboard placard was placed in windows of residences where patients

were quarantined due to poliomyelitis. Violating the quarantine order or

removing the placard was punishable by a fine of up to US$100 in 1909

(equivalent to $2,789 in 2018).

Polio was a plague. One day you had a headache and an hour later you were paralyzed. How far the virus crept up your spine determined whether you could walk afterward or even breathe. Parents waited fearfully every summer to see if it would strike. One case turned up and then another. The count began to climb. The city closed the swimming pools and we all stayed home, cooped indoors, shunning other children. Summer seemed like winter then.

Richard Rhodes, A Hole in the World

On Saturday, June 17, 1916, an official announcement of the existence an epidemic polio infection was made in Brooklyn, New York.

That year, there were over 27,000 cases and more than 6,000 deaths due

to polio in the United States, with over 2,000 deaths in New York City

alone.

The names and addresses of individuals with confirmed polio cases were

published daily in the press, their houses were identified with

placards, and their families were quarantined. Dr. Hiram M. Hiller, Jr.

was one of the physicians in several cities who realized what they were

dealing with, but the nature of the disease remained largely a mystery.

The 1916 epidemic caused widespread panic and thousands fled the city

to nearby mountain resorts; movie theaters were closed, meetings were

canceled, public gatherings were almost nonexistent, and children were

warned not to drink from water fountains, and told to avoid amusement

parks, swimming pools, and beaches.

From 1916 onward, a polio epidemic appeared each summer in at least one

part of the country, with the most serious occurring in the 1940s and

1950s.

In the epidemic of 1949, 2,720 deaths from the disease occurred in the

United States and 42,173 cases were reported and Canada and the United

Kingdom were also affected.

Prior to the 20th century polio infections were rarely seen in

infants before 6 months of age and most cases occurred in children 6

months to 4 years of age.

Young children who contract polio generally suffer only mild symptoms,

but as a result they become permanently immune to the disease. In developed countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, improvements were being made in community sanitation, including improved sewage

disposal and clean water supplies. Better hygiene meant that infants

and young children had fewer opportunities to encounter and develop

immunity to polio. Exposure to poliovirus was therefore delayed until

late childhood or adult life, when it was more likely to take the

paralytic form.

In children, paralysis due to polio occurs in one in 1000 cases, while in adults, paralysis occurs in one in 75 cases.

By 1950, the peak age incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis in the

United States had shifted from infants to children aged 5 to 9 years;

about one-third of the cases were reported in persons over 15 years of

age. Accordingly, the rate of paralysis and death due to polio infection also increased during this time.

In the United States, the 1952 polio epidemic was the worst outbreak

in the nation's history, and is credited with heightening parents’ fears

of the disease and focusing public awareness on the need for a vaccine. Of the 57,628 cases reported that year 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis.

Historical treatments

In

the early 20th century—in the absence of proven treatments—a number of

odd and potentially dangerous polio treatments were suggested. In John Haven Emerson's A Monograph on the Epidemic of Poliomyelitis (Infantile Paralysis) in New York City in 1916 one suggested remedy reads:

| “ | Give oxygen through the lower extremities, by positive electricity. Frequent baths using almond meal, or oxidising the water. Applications of poultices of Roman chamomile, slippery elm, arnica, mustard, cantharis, amygdalae dulcis oil, and of special merit, spikenard oil and Xanthoxolinum. Internally use caffeine, Fl. Kola, dry muriate of quinine, elixir of cinchone, radium water, chloride of gold, liquor calcis and wine of pepsin. | ” |

Following the 1916 epidemics and having experienced little success in

treating polio patients, researchers set out to find new and better

treatments for the disease. Between 1917 and the early 1950s several

therapies were explored in an effort to prevent deformities including hydrotherapy and electrotherapy.

In 1935 Claus Jungeblut reported that vitamin C treatment inactivates the polio virus in vitro, making it non-infectious when injected into monkeys.

In 1937, Jungeblut injected polio into the brains of monkeys, and found

that many more monkeys that also received vitamin C escaped paralysis

than controls - the results seemed to indicate that low doses were more

effective than high doses.

A subsequent study by Jungeblut demonstrated that polio infected

monkeys had lower vitamin C levels than others, and that the monkeys

that escaped paralysis had the highest vitamin C levels.

Jungeblut subsequently confirmed his findings in a larger study,

finding that natural vitamin C was more effective than synthetic vitamin

C, and as the disease progressed, larger and larger amounts of vitamin C

were needed for therapeutic effect.

In 1939, Albert Sabin reported that an experiment, employing the

technique of "forcefully expelling the total amount [of Polio] in the

direction of the olfactory mucosa, immediately drawing it back into the

pipette, and repeating the process 2 to 3 times",

was unable to confirm the results of Jungeblut, but found that "monkeys

on a scorbutic diet died of spontaneous acute infections, chiefly

pneumonia and enterocolitis, while their mates receiving an adequate

diet remained well."

Following this, Jungeblut found that "with an infection of maximum

severity, induced by flooding the nasal portal of entry with large

amounts of virus, vitamin C administration fails to exert any

demonstrable influence on the course of the disease, but with a less

forceful method of droplet instillation, the picture of the disease in

control animals becomes so variable that the results cannot be easily

interpreted; but the available data suggest that vitamin C treatment may

be a factor in converting abortive attacks into an altogether

non-paralytic infection." In 1979, R.J. Salo and D.O. Cliver inactivated Poliovirus type 1 by sodium bisulfite and ascorbic acid in an experiment.

In 1949-1953 Fred R. Klenner published his own clinical experience with vitamin C in the treatment of polio, however his work was not well received and no large clinical trials were ever performed.

Surgical treatments such as nerve grafting, tendon lengthening, tendon transfers, and limb lengthening and shortening were used extensively during this time.

Patients with residual paralysis were treated with braces and taught to

compensate for lost function with the help of calipers, crutches and

wheelchairs. The use of devices such as rigid braces and body casts, which tended to cause muscle atrophy due to the limited movement of the user, were also touted as effective treatments. Massage and passive motion exercises were also used to treat polio victims.

Most of these treatments proved to be of little therapeutic value,

however several effective supportive measures for the treatment of polio

did emerge during these decades including the iron lung, an anti-polio antibody serum, and a treatment regimen developed by Sister Elizabeth Kenny.

Iron lung

This iron lung was donated to the CDC by the family of Barton Hebert of Covington, Louisiana, who had used the device from the late 1950s until his death in 2003.

The first iron lung used in the treatment of polio victims was invented by Philip Drinker, Louis Agassiz Shaw, and James Wilson at Harvard, and tested October 12, 1928, at Children's Hospital, Boston. The original Drinker iron lung was powered by an electric motor attached to two vacuum cleaners,

and worked by changing the pressure inside the machine. When the

pressure is lowered, the chest cavity expands, trying to fill this

partial vacuum. When the pressure is raised the chest cavity contracts.

This expansion and contraction mimics the physiology of normal

breathing. The design of the iron lung was subsequently improved by

using a bellows attached directly to the machine, and John Haven Emerson modified the design to make production less expensive. The Emerson Iron Lung was produced until 1970. Other respiratory aids were used such as the Bragg-Paul Pulsator, and the "rocking bed" for patients with less critical breathing difficulties.

During the polio epidemics, the iron lung saved many thousands of

lives, but the machine was large, cumbersome and very expensive: in the 1930s, an iron lung cost about $1,500—about the same price as the average home.

The cost of running the machine was also prohibitive, as patients were

encased in the metal chambers for months, years and sometimes for life: even with an iron lung the fatality rate for patients with bulbar polio exceeded 90%.

These drawbacks led to the development of more modern

positive-pressure ventilators and the use of positive-pressure

ventilation by tracheostomy. Positive pressure ventilators reduced mortality in bulbar patients from 90% to 20%.

In the Copenhagen epidemic of 1952, large numbers of patients were

ventilated by hand ("bagged") by medical students and anyone else on

hand, because of the large number of bulbar polio patients and the small

number of ventilators available.

Passive immunotherapy

In 1950 William Hammon at the University of Pittsburgh isolated serum, containing antibodies against poliovirus, from the blood of polio survivors. The serum, Hammon believed, would prevent the spread of polio and to reduce the severity of disease in polio patients. Between September 1951 and July 1952 nearly 55,000 children were involved in a clinical trial of the anti-polio serum.

The results of the trial were promising; the serum was shown to be

about 80% effective in preventing the development of paralytic

poliomyelitis, and protection was shown to last for 5 weeks if given

under tightly controlled circumstances. The serum was also shown to reduce the severity of the disease in patients who developed polio.

The large-scale use of antibody serum to prevent and treat polio

had a number of drawbacks, however, including the observation that the

immunity provided by the serum did not last long, and the protection

offered by the antibody was incomplete, that re-injection was required

during each epidemic outbreak, and that the optimal time frame for

administration was unknown.

The antibody serum was widely administered, but obtaining the serum was

an expensive and time-consuming process, and the focus of the medical

community soon shifted to the development of a polio vaccine.

Kenny regimen

Early

management practices for paralyzed muscles emphasized the need to rest

the affected muscles and suggested that the application of splints would prevent tightening of muscle, tendons, ligaments,

or skin that would prevent normal movement. Many paralyzed polio

patients lay in plaster body casts for months at a time. This prolonged

casting often resulted in atrophy of both affected and unaffected muscles.

In 1940, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian bush nurse from Queensland,

arrived in North America and challenged this approach to treatment. In

treating polio cases in rural Australia between 1928 and 1940, Kenny had

developed a form of physical therapy

that—instead of immobilizing afflicted limbs—aimed to relieve pain and

spasms in polio patients through the use of hot, moist packs to relieve

muscle spasm and early activity and exercise to maximize the strength of

unaffected muscle fibers and promote the neuroplastic recruitment of remaining nerve cells that had not been killed by the virus. Sister Kenny later settled in Minnesota where she established the Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute,

beginning a world-wide crusade to advocate her system of treatment.

Slowly, Kenny's ideas won acceptance, and by the mid-20th century had

become the hallmark for the treatment of paralytic polio. In combination with antispasmodic medications to reduce muscular contractions, Kenny's therapy is still used in the treatment of paralytic poliomyelitis.

In 2009 as part of the Q150 celebrations, the Kenny regimen for polio treatment was announced as one of the Q150 Icons of Queensland for its role as an iconic "innovation and invention".

Vaccine development

People in Columbus, Georgia, awaiting polio vaccination during the early days of the National Polio Immunization Program.

In 1935 Maurice Brodie, a research assistant at New York University, attempted to produce a polio vaccine, procured from virus in ground up monkey spinal cords, and killed by formaldehyde.

Brodie first tested the vaccine on himself and several of his

assistants. He then gave the vaccine to three thousand children. Many

developed allergic reactions, but none of the children developed an

immunity to polio. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, a research group, headed by John Enders at the Boston Children's Hospital, successfully cultivated the poliovirus

in human tissue. This significant breakthrough ultimately allowed for

the development of the polio vaccines. Enders and his colleagues, Thomas H. Weller and Frederick C. Robbins, were recognized for their labors with the Nobel Prize in 1954.

Two vaccines are used throughout the world to combat polio. The first was developed by Jonas Salk, first tested in 1952, and announced to the world by Salk on April 12, 1955. The Salk vaccine, or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), consists of an injected dose of killed poliovirus.

In 1954, the vaccine was tested for its ability to prevent polio; the

field trials involving the Salk vaccine would grow to be the largest

medical experiment in history. Immediately following licensing, vaccination campaigns were launched, by 1957, following mass immunizations promoted by the March of Dimes the annual number of polio cases in the United States was reduced, from a peak of nearly 58,000 cases, to 5,600 cases.

Eight years after Salk's success, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using live but weakened (attenuated) virus. Human trials

of Sabin's vaccine began in 1957 and it was licensed in 1962.

Following the development of oral polio vaccine, a second wave of mass

immunizations led to a further decline in the number of cases: by 1961,

only 161 cases were recorded in the United States. The last cases of paralytic poliomyelitis caused by endemic transmission of poliovirus in the United States were in 1979, when an outbreak occurred among the Amish in several Midwestern states.

Legacy

Early in the twentieth century polio became the world's most feared disease.[citation needed] The disease hit without warning, tended to strike white, affluent individuals, required long quarantine

periods during which parents were separated from children: it was

impossible to tell who would get the disease and who would be spared. The consequences of the disease left polio victims marked for life, leaving behind vivid images of wheelchairs,

crutches, leg braces, breathing devices, and deformed limbs. However,

polio changed not only the lives of those who survived it, but also

affected profound cultural changes: the emergence of grassroots fund-raising campaigns that would revolutionize medical philanthropy,

the rise of rehabilitation therapy and, through campaigns for the

social and civil rights of the disabled, polio survivors helped to spur

the modern disability rights movement.

In addition, the occurrence of polio epidemics led to a number of

public health innovations. One of the most widespread was the

proliferation of "no spitting" ordinances in the United States and

elsewhere.

Philanthropy

In 1921 Franklin D. Roosevelt became totally and permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Although the paralysis (whether from poliomyelitis, as diagnosed at the time, or from Guillain–Barré syndrome)

had no cure at the time, Roosevelt, who had planned a life in politics,

refused to accept the limitations of his disease. He tried a wide

range of therapies, including hydrotherapy in Warm Springs, Georgia. In 1938 Roosevelt helped to found the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the March of Dimes), that raised money for the rehabilitation of victims of paralytic polio, and was instrumental in funding the development of polio vaccines.

The March of Dimes changed the way it approached fund-raising. Rather

than soliciting large contributions from a few wealthy individuals, the

March of Dimes sought small donations from millions of individuals. Its

hugely successful fund-raising campaigns collected hundreds of millions

of dollars—more than all of the U.S. charities at the time combined (with the exception of the Red Cross). By 1955 the March of Dimes had invested $25.5 million in research;

funding both Jonas Salk's and Albert Sabin's vaccine development; the

1954–55 field trial of vaccine, and supplies of free vaccine for

thousands of children.

In 1952, during the worst recorded epidemic, 3,145 people in the United States died from polio. That same year over 200,000 people (including 4,000 children) died of cancer and 20,000 (including 1,500 children) died of tuberculosis. According to David Oshinsky's book Polio: An American Story:

"There is evidence that the March of Dimes over-hyped polio, and

promoted an image of immediately curable polio victims, which was not

true. The March of Dimes refused to partner with other charity

organizations like the United Way."

Rehabilitation therapy

A physical therapist assists two polio-stricken children while they exercise their lower limbs.

Prior to the polio scares of the twentieth century, most rehabilitation therapy

was focused on treating injured soldiers returning from war. The

crippling effects of polio led to heightened awareness and public

support of physical rehabilitation, and in response a number of

rehabilitation centers specifically aimed at treating polio patients

were opened, with the task of restoring and building the remaining

strength of polio victims and teaching new, compensatory skills to large

numbers of newly paralyzed individuals.

In 1926, Franklin Roosevelt, convinced of the benefits of hydrotherapy, bought a resort at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he founded the first modern rehabilitation center for treatment of polio patients which still operates as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation.

The cost of polio rehabilitation was often more than the average

family could afford, and more than 80% of the nation's polio patients

would receive funding through the March of Dimes. Some families also received support through philanthropic organizations such as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine fraternity, which established a network of pediatric hospitals in 1919, the Shriners Hospitals for Children, to provide care free of charge for children with polio.

Disability rights movement

As

thousands of polio survivors with varying degrees of paralysis left the

rehabilitation hospitals and went home, to school and to work, many

were frustrated by a lack of accessibility and discrimination they experienced in their communities. In the early twentieth century the use of a wheelchair at home or out in public was a daunting prospect as no public transportation

system accommodated wheelchairs and most public buildings including

schools, were inaccessible to those with disabilities. Many children

left disabled by polio were forced to attend separate institutions for "crippled children" or had to be carried up and down stairs.

As people who had been paralyzed by polio matured, they began to

demand the right to participate in the mainstream of society. Polio

survivors were often in the forefront of the disability rights movement that emerged in the United States during the 1970s, and pushed legislation such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 which protected qualified individuals from discrimination based on their disability, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Other political movements led by polio survivors include the Independent Living and Universal design movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

Polio survivors are one of the largest disabled groups in the world. The World Health Organization estimates that there are 10 to 20 million polio survivors worldwide.

In 1977, the National Health Interview Survey reported that there were

254,000 people living in the United States who had been paralyzed by

polio.

According to local polio support groups and doctors, some 40,000 polio

survivors with varying degrees of paralysis live in Germany, 30,000 in

Japan, 24,000 in France, 16,000 in Australia, 12,000 in Canada and

12,000 in the United Kingdom.