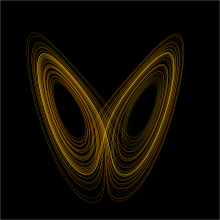

The Lorenz attractor arises in the study of the Lorenz Oscillator, a dynamical system.

In mathematics, a dynamical system is a system in which a function describes the time dependence of a point in a geometrical space. Examples include the mathematical models that describe the swinging of a clock pendulum, the flow of water in a pipe, and the number of fish each springtime in a lake.

At any given time, a dynamical system has a state given by a tuple of real numbers (a vector) that can be represented by a point in an appropriate state space (a geometrical manifold). The evolution rule of the dynamical system is a function that describes what future states follow from the current state. Often the function is deterministic, that is, for a given time interval only one future state follows from the current state. However, some systems are stochastic, in that random events also affect the evolution of the state variables.

In physics, a dynamical system

is described as a "particle or ensemble of particles whose state varies

over time and thus obeys differential equations involving time

derivatives."

In order to make a prediction about the system's future behavior, an

analytical solution of such equations or their integration over time

through computer simulation is realized.

The study of dynamical systems is the focus of dynamical systems theory, which has applications to a wide variety of fields such as mathematics, physics, biology, chemistry, engineering, economics, history, and medicine. Dynamical systems are a fundamental part of chaos theory, logistic map dynamics, bifurcation theory, the self-assembly and self-organization processes, and the edge of chaos concept.

Overview

The concept of a dynamical system has its origins in Newtonian mechanics.

There, as in other natural sciences and engineering disciplines, the

evolution rule of dynamical systems is an implicit relation that gives

the state of the system for only a short time into the future. (The

relation is either a differential equation, difference equation or other time scale.)

To determine the state for all future times requires iterating the

relation many times—each advancing time a small step. The iteration

procedure is referred to as solving the system or integrating the system.

If the system can be solved, given an initial point it is possible to

determine all its future positions, a collection of points known as a trajectory or orbit.

Before the advent of computers,

finding an orbit required sophisticated mathematical techniques and

could be accomplished only for a small class of dynamical systems.

Numerical methods implemented on electronic computing machines have

simplified the task of determining the orbits of a dynamical system.

For simple dynamical systems, knowing the trajectory is often

sufficient, but most dynamical systems are too complicated to be

understood in terms of individual trajectories. The difficulties arise

because:

- The systems studied may only be known approximately—the parameters of the system may not be known precisely or terms may be missing from the equations. The approximations used bring into question the validity or relevance of numerical solutions. To address these questions several notions of stability have been introduced in the study of dynamical systems, such as Lyapunov stability or structural stability. The stability of the dynamical system implies that there is a class of models or initial conditions for which the trajectories would be equivalent. The operation for comparing orbits to establish their equivalence changes with the different notions of stability.

- The type of trajectory may be more important than one particular trajectory. Some trajectories may be periodic, whereas others may wander through many different states of the system. Applications often require enumerating these classes or maintaining the system within one class. Classifying all possible trajectories has led to the qualitative study of dynamical systems, that is, properties that do not change under coordinate changes. Linear dynamical systems and systems that have two numbers describing a state are examples of dynamical systems where the possible classes of orbits are understood.

- The behavior of trajectories as a function of a parameter may be what is needed for an application. As a parameter is varied, the dynamical systems may have bifurcation points where the qualitative behavior of the dynamical system changes. For example, it may go from having only periodic motions to apparently erratic behavior, as in the transition to turbulence of a fluid.

- The trajectories of the system may appear erratic, as if random. In these cases it may be necessary to compute averages using one very long trajectory or many different trajectories. The averages are well defined for ergodic systems and a more detailed understanding has been worked out for hyperbolic systems. Understanding the probabilistic aspects of dynamical systems has helped establish the foundations of statistical mechanics and of chaos.

History

Many people regard French mathematician Henri Poincaré as the founder of dynamical systems.

Poincaré published two now classical monographs, "New Methods of

Celestial Mechanics" (1892–1899) and "Lectures on Celestial Mechanics"

(1905–1910). In them, he successfully applied the results of their

research to the problem of the motion of three bodies and studied in

detail the behavior of solutions (frequency, stability, asymptotic, and

so on). These papers included the Poincaré recurrence theorem,

which states that certain systems will, after a sufficiently long but

finite time, return to a state very close to the initial state.

Aleksandr Lyapunov

developed many important approximation methods. His methods, which he

developed in 1899, make it possible to define the stability of sets of

ordinary differential equations. He created the modern theory of the

stability of a dynamic system.

In 1913, George David Birkhoff proved Poincaré's "Last Geometric Theorem", a special case of the three-body problem, a result that made him world-famous. In 1927, he published his Dynamical SystemsBirkhoff's most durable result has been his 1931 discovery of what is now called the ergodic theorem. Combining insights from physics on the ergodic hypothesis with measure theory, this theorem solved, at least in principle, a fundamental problem of statistical mechanics. The ergodic theorem has also had repercussions for dynamics.

Stephen Smale made significant advances as well. His first contribution is the Smale horseshoe that jumpstarted significant research in dynamical systems. He also outlined a research program carried out by many others.

Oleksandr Mykolaiovych Sharkovsky developed Sharkovsky's theorem on the periods of discrete dynamical systems in 1964. One of the implications of the theorem is that if a discrete dynamical system on the real line has a periodic point of period 3, then it must have periodic points of every other period.

In the late 20th century, Palestinian mechanical engineer Ali H. Nayfeh applied nonlinear dynamics in mechanical and engineering systems. His pioneering work in applied nonlinear dynamics has been influential in the construction and maintenance of machines and structures that are common in daily life, such as ships, cranes, bridges, buildings, skyscrapers, jet engines, rocket engines, aircraft and spacecraft.

Basic definitions

A dynamical system is a manifold M called the phase (or state) space endowed with a family of smooth evolution functions Φt that for any element of t ∈ T, the time, map a point of the phase space

back into the phase space. The notion of smoothness changes with

applications and the type of manifold. There are several choices for

the set T. When T is taken to be the reals, the dynamical system is called a flow; and if T is restricted to the non-negative reals, then the dynamical system is a semi-flow. When T is taken to be the integers, it is a cascade or a map; and the restriction to the non-negative integers is a semi-cascade.

Examples

The evolution function Φ t is often the solution of a differential equation of motion

The equation gives the time derivative, represented by the dot, of a trajectory x(t) on the phase space starting at some point x0. The vector field v(x) is a smooth function that at every point of the phase space M provides the velocity vector of the dynamical system at that point. (These vectors are not vectors in the phase space M, but in the tangent space TxM of the point x.) Given a smooth Φ t, an autonomous vector field can be derived from it.

There is no need for higher order derivatives in the equation, nor for time dependence in v(x) because these can be eliminated by considering systems of higher dimensions. Other types of differential equations can be used to define the evolution rule:

is an example of an equation that arises from the modeling of mechanical systems with complicated constraints.

The differential equations determining the evolution function Φ t are often ordinary differential equations; in this case the phase space M

is a finite dimensional manifold. Many of the concepts in dynamical

systems can be extended to infinite-dimensional manifolds—those that are

locally Banach spaces—in which case the differential equations are partial differential equations. In the late 20th century the dynamical system perspective to partial differential equations started gaining popularity.

Further examples

- Logistic map

- Complex quadratic polynomial

- Dyadic transformation

- Tent map

- Double pendulum

- Arnold's cat map

- Horseshoe map

- Baker's map is an example of a chaotic piecewise linear map

- Billiards and outer billiards

- Hénon map

- Lorenz system

- Circle map

- Rössler map

- Kaplan–Yorke map

- List of chaotic maps

- Swinging Atwood's machine

- Quadratic map simulation system

- Bouncing ball dynamics

Linear dynamical systems

Linear dynamical systems can be solved in terms of simple functions

and the behavior of all orbits classified. In a linear system the phase

space is the N-dimensional Euclidean space, so any point in phase space can be represented by a vector with N numbers. The analysis of linear systems is possible because they satisfy a superposition principle: if u(t) and w(t) satisfy the differential equation for the vector field (but not necessarily the initial condition), then so will u(t) + w(t).

Flows

For a flow, the vector field Φ(x) is an affine function of the position in the phase space, that is,

with A a matrix, b a vector of numbers and x the position vector. The solution to this system can be found by using the superposition principle (linearity).

The case b ≠ 0 with A = 0 is just a straight line in the direction of b:

When b is zero and A ≠ 0 the origin is an equilibrium (or singular) point of the flow, that is, if x0 = 0, then the orbit remains there.

For other initial conditions, the equation of motion is given by the exponential of a matrix: for an initial point x0,

When b = 0, the eigenvalues of A determine the structure of the phase space. From the eigenvalues and the eigenvectors of A it is possible to determine if an initial point will converge or diverge to the equilibrium point at the origin.

The distance between two different initial conditions in the case A ≠ 0

will change exponentially in most cases, either converging

exponentially fast towards a point, or diverging exponentially fast.

Linear systems display sensitive dependence on initial conditions in the

case of divergence. For nonlinear systems this is one of the (necessary

but not sufficient) conditions for chaotic behavior.

Linear vector fields and a few trajectories.

Maps

with A a matrix and b a vector. As in the continuous case, the change of coordinates x → x + (1 − A) –1b removes the term b from the equation. In the new coordinate system, the origin is a fixed point of the map and the solutions are of the linear system A nx0.

The solutions for the map are no longer curves, but points that hop in

the phase space. The orbits are organized in curves, or fibers, which

are collections of points that map into themselves under the action of

the map.

As in the continuous case, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A determine the structure of phase space. For example, if u1 is an eigenvector of A, with a real eigenvalue smaller than one, then the straight lines given by the points along α u1, with α ∈ R, is an invariant curve of the map. Points in this straight line run into the fixed point.

There are also many other discrete dynamical systems.

Local dynamics

The

qualitative properties of dynamical systems do not change under a

smooth change of coordinates (this is sometimes taken as a definition of

qualitative): a singular point of the vector field (a point where v(x) = 0) will remain a singular point under smooth transformations; a periodic orbit

is a loop in phase space and smooth deformations of the phase space

cannot alter it being a loop. It is in the neighborhood of singular

points and periodic orbits that the structure of a phase space of a

dynamical system can be well understood. In the qualitative study of

dynamical systems, the approach is to show that there is a change of

coordinates (usually unspecified, but computable) that makes the

dynamical system as simple as possible.

Rectification

A flow in most small patches of the phase space can be made very simple. If y is a point where the vector field v(y) ≠ 0, then there is a change of coordinates for a region around y where the vector field becomes a series of parallel vectors of the same magnitude. This is known as the rectification theorem.

The rectification theorem says that away from singular points

the dynamics of a point in a small patch is a straight line. The patch

can sometimes be enlarged by stitching several patches together, and

when this works out in the whole phase space M the dynamical system is integrable.

In most cases the patch cannot be extended to the entire phase space.

There may be singular points in the vector field (where v(x) = 0);

or the patches may become smaller and smaller as some point is

approached. The more subtle reason is a global constraint, where the

trajectory starts out in a patch, and after visiting a series of other

patches comes back to the original one. If the next time the orbit loops

around phase space in a different way, then it is impossible to rectify

the vector field in the whole series of patches.

Near periodic orbits

In

general, in the neighborhood of a periodic orbit the rectification

theorem cannot be used. Poincaré developed an approach that transforms

the analysis near a periodic orbit to the analysis of a map. Pick a

point x0 in the orbit γ and consider the points in phase space in that neighborhood that are perpendicular to v(x0). These points are a Poincaré section S(γ, x0), of the orbit. The flow now defines a map, the Poincaré map F : S → S, for points starting in S and returning to S. Not all these points will take the same amount of time to come back, but the times will be close to the time it takes x0.

The intersection of the periodic orbit with the Poincaré section is a fixed point of the Poincaré map F. By a translation, the point can be assumed to be at x = 0. The Taylor series of the map is F(x) = J · x + O(x2), so a change of coordinates h can only be expected to simplify F to its linear part

This is known as the conjugation equation. Finding conditions for

this equation to hold has been one of the major tasks of research in

dynamical systems. Poincaré first approached it assuming all functions

to be analytic and in the process discovered the non-resonant condition.

If λ1, ..., λν are the eigenvalues of J they will be resonant if one eigenvalue is an integer linear combination of two or more of the others. As terms of the form λi – ∑ (multiples of other eigenvalues) occurs in the denominator of the terms for the function h, the non-resonant condition is also known as the small divisor problem.

Conjugation results

The results on the existence of a solution to the conjugation equation depend on the eigenvalues of J and the degree of smoothness required from h. As J does not need to have any special symmetries, its eigenvalues will typically be complex numbers. When the eigenvalues of J are not in the unit circle, the dynamics near the fixed point x0 of F is called hyperbolic and when the eigenvalues are on the unit circle and complex, the dynamics is called elliptic.

In the hyperbolic case, the Hartman–Grobman theorem

gives the conditions for the existence of a continuous function that

maps the neighborhood of the fixed point of the map to the linear map J · x. The hyperbolic case is also structurally stable.

Small changes in the vector field will only produce small changes in

the Poincaré map and these small changes will reflect in small changes

in the position of the eigenvalues of J in the complex plane, implying that the map is still hyperbolic.

The Kolmogorov–Arnold–Moser (KAM) theorem gives the behavior near an elliptic point.

Bifurcation theory

When the evolution map Φt (or the vector field

it is derived from) depends on a parameter μ, the structure of the

phase space will also depend on this parameter. Small changes may

produce no qualitative changes in the phase space until a special value μ0

is reached. At this point the phase space changes qualitatively and

the dynamical system is said to have gone through a bifurcation.

Bifurcation theory considers a structure in phase space (typically a fixed point, a periodic orbit, or an invariant torus) and studies its behavior as a function of the parameter μ.

At the bifurcation point the structure may change its stability, split

into new structures, or merge with other structures. By using Taylor

series approximations of the maps and an understanding of the

differences that may be eliminated by a change of coordinates, it is

possible to catalog the bifurcations of dynamical systems.

The bifurcations of a hyperbolic fixed point x0 of a system family Fμ can be characterized by the eigenvalues of the first derivative of the system DFμ(x0) computed at the bifurcation point. For a map, the bifurcation will occur when there are eigenvalues of DFμ

on the unit circle. For a flow, it will occur when there are

eigenvalues on the imaginary axis. For more information, see the main

article on Bifurcation theory.

Some bifurcations can lead to very complicated structures in phase space. For example, the Ruelle–Takens scenario describes how a periodic orbit bifurcates into a torus and the torus into a strange attractor. In another example, Feigenbaum period-doubling describes how a stable periodic orbit goes through a series of period-doubling bifurcations.

Ergodic systems

In many dynamical systems, it is possible to choose the coordinates

of the system so that the volume (really a ν-dimensional volume) in

phase space is invariant. This happens for mechanical systems derived

from Newton's laws as long as the coordinates are the position and the

momentum and the volume is measured in units of (position) × (momentum).

The flow takes points of a subset A into the points Φ t(A) and invariance of the phase space means that

In the Hamiltonian formalism,

given a coordinate it is possible to derive the appropriate

(generalized) momentum such that the associated volume is preserved by

the flow. The volume is said to be computed by the Liouville measure.

In a Hamiltonian system, not all possible configurations of

position and momentum can be reached from an initial condition. Because

of energy conservation, only the states with the same energy as the

initial condition are accessible. The states with the same energy form

an energy shell Ω, a sub-manifold of the phase space. The volume of the

energy shell, computed using the Liouville measure, is preserved under

evolution.

For systems where the volume is preserved by the flow, Poincaré discovered the recurrence theorem: Assume the phase space has a finite Liouville volume and let F be a phase space volume-preserving map and A a subset of the phase space. Then almost every point of A returns to A infinitely often. The Poincaré recurrence theorem was used by Zermelo to object to Boltzmann's derivation of the increase in entropy in a dynamical system of colliding atoms.

One of the questions raised by Boltzmann's work was the possible

equality between time averages and space averages, what he called the ergodic hypothesis. The hypothesis states that the length of time a typical trajectory spends in a region A is vol(A)/vol(Ω).

The ergodic hypothesis turned out not to be the essential property needed for the development of statistical mechanics and a series of other ergodic-like properties were introduced to capture the relevant aspects of physical systems. Koopman approached the study of ergodic systems by the use of functional analysis. An observable a

is a function that to each point of the phase space associates a number

(say instantaneous pressure, or average height). The value of an

observable can be computed at another time by using the evolution

function φ t. This introduces an operator U t, the transfer operator,

By studying the spectral properties of the linear operator U it becomes possible to classify the ergodic properties of Φ t.

In using the Koopman approach of considering the action of the flow on

an observable function, the finite-dimensional nonlinear problem

involving Φ t gets mapped into an infinite-dimensional linear problem involving U.

The Liouville measure restricted to the energy surface Ω is the basis for the averages computed in equilibrium statistical mechanics. An average in time along a trajectory is equivalent to an average in space computed with the Boltzmann factor exp(−βH).

This idea has been generalized by Sinai, Bowen, and Ruelle (SRB) to a

larger class of dynamical systems that includes dissipative systems. SRB measures replace the Boltzmann factor and they are defined on attractors of chaotic systems.

Nonlinear dynamical systems and chaos

Simple nonlinear dynamical systems and even piecewise linear systems

can exhibit a completely unpredictable behavior, which might seem to be

random, despite the fact that they are fundamentally deterministic. This

seemingly unpredictable behavior has been called chaos. Hyperbolic systems

are precisely defined dynamical systems that exhibit the properties

ascribed to chaotic systems. In hyperbolic systems the tangent space

perpendicular to a trajectory can be well separated into two parts: one

with the points that converge towards the orbit (the stable manifold) and another of the points that diverge from the orbit (the unstable manifold).

This branch of mathematics

deals with the long-term qualitative behavior of dynamical systems.

Here, the focus is not on finding precise solutions to the equations

defining the dynamical system (which is often hopeless), but rather to

answer questions like "Will the system settle down to a steady state in the long term, and if so, what are the possible attractors?" or "Does the long-term behavior of the system depend on its initial condition?"

Note that the chaotic behavior of complex systems is not the issue. Meteorology

has been known for years to involve complex—even chaotic—behavior.

Chaos theory has been so surprising because chaos can be found within

almost trivial systems. The logistic map is only a second-degree polynomial; the horseshoe map is piecewise linear.

Geometrical definition

A dynamical system is the tuple , with a manifold (locally a Banach space or Euclidean space), the domain for time (non-negative reals, the integers, ...) and f an evolution rule t → f t (with ) such that f t is a diffeomorphism of the manifold to itself. So, f is a mapping of the time-domain into the space of diffeomorphisms of the manifold to itself. In other terms, f(t) is a diffeomorphism, for every time t in the domain .

Measure theoretical definition

A dynamical system may be defined formally, as a measure-preserving transformation of a sigma-algebra, the quadruplet (X, Σ, μ, τ). Here, X is a set, and Σ is a sigma-algebra on X, so that the pair (X, Σ) is a measurable space. μ is a finite measure on the sigma-algebra, so that the triplet (X, Σ, μ) is a probability space. A map τ: X → X is said to be Σ-measurable if and only if, for every σ ∈ Σ, one has . A map τ is said to preserve the measure if and only if, for every σ ∈ Σ, one has . Combining the above, a map τ is said to be a measure-preserving transformation of X , if it is a map from X to itself, it is Σ-measurable, and is measure-preserving. The quadruple (X, Σ, μ, τ), for such a τ, is then defined to be a dynamical system.

The map τ embodies the time evolution of the dynamical system. Thus, for discrete dynamical systems the iterates for integer n

are studied. For continuous dynamical systems, the map τ is understood

to be a finite time evolution map and the construction is more

complicated.

Examples of dynamical systems

- Arnold's cat map

- Baker's map is an example of a chaotic piecewise linear map

- Circle map

- Double pendulum

- Billiards and Outer billiards

- Hénon map

- Horseshoe map

- Irrational rotation

- List of chaotic maps

- Logistic map

- Lorenz system

- Rossler map

Multidimensional generalization

Dynamical

systems are defined over a single independent variable, usually thought

of as time. A more general class of systems are defined over multiple

independent variables and are therefore called multidimensional systems. Such systems are useful for modeling, for example, image processing.