| Homo erectus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of Tautavel Man | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: |

H. erectus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Homo erectus

(Dubois, 1893)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Homo erectus (meaning 'upright man') were a species of archaic humans from the Pleistocene, earliest occurrence about 2 mya. They are proposed to be the direct ancestors to several human species, such as H. heidelbergensis, H. antecessor, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans. As a chronospecies, the time of its disappearance is thus a matter of contention or even convention. There are also several proposed subspecies with varying levels of recognition.

H. erectus appear to have been much more similar to modern humans than to their ancestors, the australopithecines, with a more humanlike gait, body proportions, height, and brain capacity. H. erectus are associated with the Acheulean stone tool industry, and is thought to be the earliest human ancestor capable of starting fires, speech, hunting and gathering in coordinated groups, caring for injured or sick group members, and possibly art-making.

Taxonomy

Naming

The first remains, Java Man, were described by Dutch anatomist Eugène Dubois in 1893, who set out to look for the "missing link" between apes and humans in Southeast Asia, because he believed gibbons to be the closest living relatives to humans in accordance with the "Out of Asia" hypothesis. H. erectus was the first fossil hominin found as a result of a directed expedition.

Excavated from the bank of the Solo River at Trinil, East Java, he first allocated the material to a genus of fossil chimpanzees as Anthropopithecus erectus, then the following year assigned it to a new genus as Pithecanthropus erectus (the genus name had been coined by Ernst Haeckel in 1868 for the hypothetical link between humans and fossil Apes). The species name erectus was given because the femur suggested that Java Man had been bipedal

and walked upright. However, few scientists recognized it as a "missing

link", and, consequently, Dubois' discovery had been largely

disregarded.

Forensic reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus.

In 1921, two teeth from Zhoukoudian, China discovered by Johan Gunnar Andersson had prompted widely publicized interest. When describing the teeth, Davidson Black named it a new species Sinanthropus pekinensis from Ancient Greek Σίνα sino- "China" and Latin pekinensis

"of Peking". Subsequent excavations uncovered about 200 human fossils

from more than 40 individuals including five nearly complete skullcaps.

Franz Weidenreich provided much of the detailed description of this material in several monographs published in the journal Palaeontologica Sinica (Series D). Nearly all of the original specimens were lost during World War II during an attempt to smuggle them out of China for safekeeping. However, casts were made by Weidenreich, which exist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

Similarities between Java Man and Peking Man led Ernst Mayr to rename both as Homo erectus in 1950. Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of H. erectus in human evolution.

Early in the century, due in part to the discoveries at Java and

Zhoukoudian, the belief that modern humans first evolved in Asia was

widely accepted. A few naturalists—Charles Darwin

the most prominent among them—theorized that humans' earliest ancestors

were African. Darwin pointed out that chimpanzees and gorillas, humans'

closest relatives, evolved and exist only in Africa.

Evolution

Forensic reconstruction of an adult male Homo erectus.

It has been proposed that H. erectus evolved from H. habilis

about 2 mya, though this has been called into question because they

coexisted for at least a half a million years. Alternatively, a group of

H. habilis may have been reproductively isolated, and only this group developed into H. erectus (cladogenesis).

Because the earliest remains of H. erectus are found in both Africa and East Asia (in China as early as 2.1 mya), it is debated where H. erectus evolved. A 2011 study suggested that it was H. habilis who reached West Asia, that early H. erectus developed there, and that early H. erectus would then have dispersed from West Asia to East Asia (Peking Man), Southeast Asia (Java Man), back to Africa (Homo ergaster), and to Europe (Tautavel Man), eventually evolving into modern humans in Africa. Others have suggested that H. erectus/H. ergaster developed in Africa, where it eventually evolved into modern humans.

Subspecies

- Homo erectus bilzingslebenensis (0.37 Ma)

- Homo erectus erectus (Java Man, 1.6–0.5 Ma)

- Homo erectus ergaster (1.9–1.4 Ma)

- Homo erectus georgicus (1.8–1.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus heidelbergensis (0.7–0.3 Ma), evidence exists of archaic human presence in Europe before 1 mya, as early as 1.6 mya.

- Homo erectus lantianensis (Lantian Man, 1.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus nankinensis (Nanjing Man, 0.6 Ma)

- Homo erectus palaeojavanicus (Meganthropus, 1.4–0.9 Ma)

- Homo erectus pekinensis (Peking Man, 0.7 Ma)

- Homo erectus soloensis (Solo Man, 0.546–0.143 Ma)

- Homo erectus tautavelensis (Tautavel Man, 0.45 Ma)

- Homo erectus yuanmouensis (Yuanmou Man)

"Wushan Man" was proposed as Homo erectus wushanensis, but is now thought to be based upon fossilized fragments of an extinct non-hominin ape.

Since its discovery in 1893 (Java man), there has been a trend in palaeoanthropology of reducing the number of proposed species of Homo, to the point where H. erectus includes all early (Lower Paleolithic) forms of Homo sufficiently derived from H. habilis and

distinct from early H. heidelbergensis (in Africa also known as H. rhodesiensis). It is sometimes considered as a wide-ranging, polymorphous species.

Reconstruction of Homo georgicus based on D2700, by Élisabeth Daynès, Museo de la Evolución Humana, Spain.

Due to such a wide range of variation, it has been suggested that the ancient H. rudolfensis and H. habilis should be considered early varieties of H. erectus. The primitive H. e. georgicus from Dmanisi,

Georgia has the smallest brain capacity of any known Pleistocene

hominin (about 600 cc), and its inclusion in the species would greatly

expand the range of variation of H. erectus to perhaps include species as H. rudolfensis, H. gautengensis, H. ergaster, and perhaps H. habilis. However, a 2015 study suggested that H. georgicus represents an earlier, more primitive species of Homo derived from an older dispersal of hominins from Africa, with H. ergaster/erectus possibly deriving from a later dispersal. H. georgicus is sometimes not even regarded as H. erectus.

It is debated whether the African H. e. ergaster is a separate species (and that H. erectus evolved in Asia, then migrated to Africa), or is the African form (sensu lato) of H. erectus (sensu stricto). In the latter, H. ergaster has also been suggested to represent the immediate ancestor of H. erectus. It has also been suggested that H. ergaster instead of H. erectus, or some hybrid between the two, was the immediate ancestor of other archaic humans and modern humans.

In a wider sense, H. erectus had mostly been replaced by H. heidelbergensis by about 300 kya years ago, with possible late survival of H. erectus soloensis in Java an estimated 546–143 kya.

Dmanisi skull 3 (fossils skull D2700 and jaw D2735, two of several found in Dmanisi in the Georgian Transcaucasus)

Descendents and synonyms

Homo erectus is the most long-lived species of Homo, having survived for over a million years. By contrast, Homo sapiens emerged about a quarter million years ago.

Regarding many archaic humans, there is no definite consensus as to whether they should be classified as subspecies of H. erectus or H. sapiens or as separate species.

- African H. erectus candidates

- Homo ergaster ("African H. erectus")

- Homo naledi (or H. e. naledi)

- Eurasian H. erectus candidates:

- Homo antecessor (or H. e. antecessor)

- Homo heidelbergensis (or H. e. heidelbergensis)

- Homo cepranensis (or H. e. cepranensis)

- Homo floresiensis

- Homo sapiens candidates

- Homo neanderthalensis (or H. s. neanderthalensis)

- Homo denisova (or H. s. denisova or Homo sp. Altai, and Homo sapiens subsp. Denisova)

- Homo rhodesiensis (or H. s. rhodensis)

- Homo heidelbergensis (or H. s. heidelbergensis)

- Homo sapiens idaltu

- the Narmada fossil, discovered in 1982 in Madhya Pradesh, India, was at first suggested as H. erectus (Homo erectus narmadensis) but later recognized as H. sapiens.

If considering Homo erectus in its strict sense (that is, as

referring to only the Asian variety) no consensus has been reached as to

whether it is ancestral to H. sapiens or any later human species. Similarly, H. antecessor and sisters, including modern humans, appear to have emerged specifically as sister of, for example, the Asian variety of H. erectus. Moreover, some late H. erectus varieties may have introgressed into the Denisovans, which then later introgressed into H. sapiens. However, it is conventional to label European archaic humans as H. heidelbergensis, the immediate predecessor of Neanderthals.

Meganthropus refers to a group of fossils found in Java, dated to between 1.4 and 0.9 Mya, which are tentatively grouped with H. erectus,

at least in the wider sense of the term in which "all earlier Homo

populations that are sufficiently derived from African early Homo belong to H. erectus", although older literature has placed the fossils outside of Homo altogether.

Anatomy

One of the features distinguishing H. erectus from H. sapiens is the size difference in teeth. H. erectus has large teeth while H. sapiens have smaller teeth. One theory for the reason of H. erectus having larger teeth is because of the requirements for eating raw meat instead of cooked meat like H. sapiens.

Foot tracks found in 2009 in Kenya confirmed that the gait of H. erectus was heel-to-toe, more like modern humans than australopithecines.

H. erectus fossils show a cranial capacity greater than that of Homo habilis

(although the Dmanisi specimens have distinctively small crania): the

earliest fossils show a cranial capacity of 850 cm³, while later Javan

specimens measure up to 1100 cm³, overlapping that of H. sapiens.

The frontal bone is less sloped and the dental arcade smaller than that of the australopithecines; the face is more prognathic (less protrusive) than australopithecines or H. habilis, with large brow-ridges and less prominent cheekbones.

H. erectus is estimated to have had an average height of 1.8 m (5.9 ft), similar to modern humans. Males were about 25% larger than females, a difference slightly greater than that seen in modern humans, but less than that of Australopithecus. H. erectus is thought to have been quite slender, with long arms and legs.

Throwing performance may have been an important mode for early hunting and defense in the genus Homo, linked to several anatomical shifts. H. erectus

may have had a shoulder configuration similar to humans,

laterally-facing with respect to the torso. This suggests that the

ability for high speed throwing can be dated back to nearly two million

years ago.

Culture

Technology

H. erectus is credited with inventing the Acheulean stone tool industry, succeeding the Oldowan industry,

and were the first to make hand axes out of stone. Though larger and

heavier, these hand axes had sharper, chiseled edges, likely used in

butchering. Such tools could indicate H. erectus had the ability of foresight and could plan steps ahead in order to create them.

The earliest record of Achuelean technology comes from West Turkana,

Kenya 1.76 mya. Oldowan lithics are also known from the site, and the

two seemed to coexist for some time. The earliest records of Achuelean

technology outside of Africa date to no older than 1 mya, indicating it

only became widespread after some secondary H. erectus dispersal from Africa.

It has been suggested that the Asian H. erectus may have been the first humans to use rafts to travel over bodies of water, including oceans. The oldest stone tool found in Turkey reveals that hominins passed through the Anatolian gateway from western Asia to Europe approximately 1.2 million years ago—much earlier than previously thought.

Use of fire

A site at Bnot Ya'akov Bridge, Israel is reported to show evidence that H. erectus or H. ergaster controlled fire there between 790,000 and 690,000 years ago; to date this claim has been widely accepted. Some evidence is found that H. erectus was controlling fire less than 250,000 years ago. Evidence also exists that H. erectus were cooking their food as early as 500,000 years ago. Re-analysis of burnt bone fragments and plant ashes from the Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, could be considered evidence of cooking as early as 1 mya.

Several East African sites show some evidence of early fire usage. At Chesowanja, there is evidence of 1.42 Ma fire-hardened clay heated to about 400 °C (752 °F), consistent with campfires. At two sites in Koobi Fora,

there is a reddening of sediment associated with heating the material

to 200–400 degrees Celsius (392–752 degrees Fahrenheit). There is a

hearth-like depression with traces of charcoal at Olorgesailie, but this could have resulted from a natural bush fire.

In Gadeb, Ethiopia, fragments of welded tuff that appeared to have been burned or scorched were found alongside Acheulean artifacts. However, such re-firing of the rocks may have been caused by local volcanic activity. In the Middle Awash

River Valley, cone-shaped depressions of reddish clay were found that

could have been created only by temperatures of 200 °C (392 °F) or

greater. These depressions may have been burnt tree stumps, and the fire

made far from the habitation site. Burnt stones are found in the Awash Valley, but naturally burnt (volcanic) welded tuff is also found in the area.

Encampments

Remains of H. erectus have more consistently been found in lake beds and in stream sediments. This suggest that H. erectus also lived in open encampments near streams and lakes.

There has been evidence of H. erectus inhabiting a cave in Zhoukoudian, China.

This evidence consisted of remains, stones, charred animal bones,

collections of seeds, and possibly ancient hearths and charcoal. Although this does not prove that H. erectus lived in caves, it does show that H. erectus spent periods of time in caves of Zhoukoudian.

Engravings

Shell from Trinil, Java with geometric incisions, dated ca. 500,000 BP, has been claimed as an early expression of art. Now in the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Netherlands.

An engraved shell with geometric markings could possibly be evidence

of the earliest art-making, dating back to 546–436 kya. Art-making

capabilities could be considered evidence of symbolic thinking, which is

associated with modern cognition and behavior.

Sociality

Homo erectus was probably the first hominin to live in a hunter-gatherer society, and anthropologists such as Richard Leakey believe that H. erectus

was socially more like modern humans than australopithecines. Likewise,

increased cranial capacity generally correlates to the more

sophisticated tools H. erectus are associated with.

The discovery of Turkana boy (H. ergaster) in 1984 evidenced that, despite its Homo sapiens-like anatomy, ergaster may not have been capable of producing sounds comparable to modern human speech. It likely communicated in a proto-language, lacking the fully developed structure of modern human language, but more developed than the non-verbal communication used by chimpanzees. This inference is challenged by the find in Dmanisi,

Georgia, of a vertebra (at least 150,000 years earlier than the Turkana

Boy) that reflects vocal capabilities within the range of H. sapiens. Both brain size and the presence of the Broca's area also support the use of articulate language.

H. erectus was probably the first hominin to live in small, familiar band-societies similar to modern hunter-gatherers,

and is thought to be the first hominin species to hunt in coordinated

groups, to use complex tools, and to care for infirm or weak companions.

It is unknown if they wore clothes and had tools such as bowls and

utensils.

Fossils

The lower cave of the Zhoukoudian cave, China, is one of the most important archaeological sites worldwide. There have been remains of 45 homo erectus individuals found and thousands of tools recovered.

Most of these remains were lost during World War 2, with the exception

of two postcranial elements that were rediscovered in China in 1951 and

four human teeth from 'Dragon Bone Hill'.

New evidence has shown that Homo erectus does not have uniquely thick vault bones, like what was previously thought. Testing showed that neither Asian or African Homo erectus had uniquely large vault bones.

Individual fossils

Some of the major Homo erectus fossils:

- Indonesia (island of Java): Trinil 2 (holotype), Sangiran collection, Sambungmachan collection, Ngandong collection

- China ("Peking Man"): Lantian (Gongwangling and Chenjiawo), Yunxian, Zhoukoudian, Nanjing, Hexian

- Kenya: KNM ER 3883, KNM ER 3733

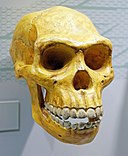

Homo erectus KNM ER 3733 actual skull

- Vietnam: Northern, Tham Khuyen, Hoa Binh

- Republic of Georgia: Dmanisi collection ("Homo erectus georgicus")

- Ethiopia: Daka calvaria

- Eritrea: Buia cranium (possibly H. ergaster)

- Denizli Province, Turkey: Kocabas fossil