Cover of the first edition

| |

| Author | Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subjects | Sigmund Freud Freud's seduction theory |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus and Giroux |

Publication date

| 1984 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 308 (first edition) 343 (1998 Pocket books edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0345452795 |

The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory is a book by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, in which the author argues that Sigmund Freud deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because he refused to believe that children are the victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families. Masson reached this conclusion while he had access to some of Freud's unpublished letters as projects director of the Sigmund Freud Archives. The Assault on Truth was first published in 1984, and several revised editions have since been published.

The book aroused massive publicity and controversy. It received many negative reviews, several of which rejected Masson's reading of psychoanalytic history, was condemned by reviewers within the psychoanalytic profession, and came to be seen as the latest in a series of attacks on psychoanalysis and an expression of a widespread "anti-Freudian mood". Its overall reception has been described as mixed. Some feminists endorsed Masson's conclusions and other commentators have seen merit in his book despite its failings. Masson has been criticized for maintaining without evidence that the seduction theory was correct, for his discussion of Freud's treatment of his patient Emma Eckstein, for suggesting that children are by nature innocent and asexual, and for taking part in a reaction against the sexual revolution. Masson has also been blamed for encouraging the recovered memory movement by implying that a collective effort to retrieve painful memories of incest was required, although he has rejected the accusation as unfounded.

Background

Formerly

a Sanskrit professor, Masson retrained as a psychoanalyst, and in the

1970s found support within the psychoanalytic profession in the United

States. His relationship with the psychoanalyst Kurt R. Eissler

helped him become the projects director of the Freud Archives, where he

was entrusted with publishing the authorized edition of the

correspondence between Freud and Wilhelm Fliess.

Masson aroused controversy after presenting his views about the origins

of Freud's psychoanalytic theories in a paper delivered at a 1981

meeting of the Western New England Psychoanalytic Society. The New York Times printed two articles reporting Masson's views, as well as an interview with him. Eissler fired Masson, who retaliated with writs. The journalist Janet Malcolm published two long articles about the controversy in The New Yorker, which were later issued as a book, In the Freud Archives (1984).

Summary

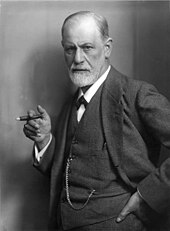

Sigmund

Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Masson argues that Freud

deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction

theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because

he refused to believe that children are abused within their own

families.

Masson argues that the accepted account of Sigmund Freud's abandonment of his seduction theory

is incorrect. According to Masson, Freud's female patients told him in

1895 and 1896 that they had been abused as children, but Freud later

came to disbelieve their accounts. He argues that Freud was wrong to

disbelieve his female patients and that the real reason Freud abandoned

the seduction theory is that he could not accept that children are "the

victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families". He suggests that Freud's theories of "internal fantasy and of spontaneous childhood sexuality",

which he developed after abandoning the seduction theory, allowed

sexual violence to be attributed to the victim's imagination, and

therefore posed no threat to the existing social order. Masson

acknowledges the tentative nature of his reinterpretation of Freud's

reasons for abandoning the seduction theory. He discusses Freud's 1896

essay "The Aetiology of Hysteria", which he provides in an appendix. He also discusses the work of the doctor Auguste Ambroise Tardieu, Freud's treatment of Emma Eckstein, Freud's theory of the Oedipus complex, and Freud's relationship with the psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi.

Publication history

The Assault on Truth was first published in 1984. Revised editions followed in 1985, 1992, 1998, and 2003.

Reception

Mainstream media

The Assault on Truth received negative reviews from the historian Peter Gay in The Philadelphia Inquirer, the psychoanalyst Anthony Storr in The New York Times Book Review, Stephen A. Mitchell in Library Journal, Herbert Wray in Psychology Today, the psychoanalyst Charles Rycroft in The New York Review of Books, the philosopher Arnold Davidson in the London Review of Books, the philosopher Frank Cioffi in The Times Literary Supplement, and a positive review from the psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman in The Nation. It was also reviewed by Paul Robinson in The New Republic, Elaine Hoffman Baruch in The New Leader, Michael Heffernan in New Statesman, Thomas H. Thompson in North American Review, F. S. Schwarzbach in The Southern Review, the psychiatrist Bob Johnson in New Scientist, and by Newsweek, Ms., The Economist, and Choice. The book was discussed by the critic Harold Bloom in The New York Times Book Review, Jenny Turner in New Statesman and Society, the critic Frederick Crews in The New York Review of Books, and by Maclean's.

Storr dismissed the book and denied that Freud would have

abandoned a theory "because it was unacceptable to the medical

establishment".

Mitchell wrote that while Masson provided fascinating excerpts from

important documents relating to Freud that had previously been carefully

guarded, his conclusions were "characterized by a bitter

tendentiousness, simplistic rhetoric, and a serious lack of

comprehension of the subtleties of later psychoanalyic theorizing." Wray dismissed Masson's arguments as "speculative".

Rycroft maintained that because Masson chose to present his work as a

polemical attack on Freud, it did not qualify as a contribution to the

early history of psychoanalysis. He accused Masson of ignoring contrary

evidence and presenting unconvincing evidence, and of being unable to

"distinguish between "facts, inferences, and speculations", but granted

that Masson had discovered some information likely to permanently damage

Freud's image, including evidence that Freud was more familiar with the

forensic literature on child abuse than his works suggested, which

showed that Freud's "eventual incredulity about the stories his

hysterical patients had told him cannot have derived from the

sentimental idea that such things just don’t happen." It also included

details about Freud and Fliess's bungled treatment of Eckstein, and

evidence that Freud’s repudiation of Ferenczi and his 1932 paper

“Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child” "was provoked by

Ferenczi’s having rediscovered the truth of the seduction theory that he

had suppressed thirty-five years." He criticized Masson for wanting to

re-establish the truth of the seduction theory without presenting

evidence that it was actually correct, and concluded that his work was

"distasteful, misguided, and at times silly." Masson replied to Rycroft's review, defending his work and accusing Rycroft of various errors.

Herman described the book as well-documented, well-written,

carefully reasoned, and fascinating. However, she suggested that

Masson's charge that Freud abandoned the seduction theory out of

personal cowardice might be overly harsh, arguing that it overstated the

role of Freud as an individual and ignored the general secrecy

surrounding the issues of rape and incest. She wrote that while Masson

did not definitively resolve the question of why Freud abandoned the

seduction theory, he was right to reopen the issue. She credited Masson

with demonstrating that once Freud abandoned the seduction theory, any

further consideration of its possible validity became "a heresy" within

psychoanalysis. She also praised Masson for documenting Freud's attempt

to stop Ferenczi from publicizing his rediscovery of "the kind of

clinical data on which the seduction theory was based". She criticized

the press coverage that The Assault on Truth had received,

writing that the press had attempted to defend a "psychoanalytic

establishment" that had been rendered "speechless" by it. According to

Herman, reviews of The Assault on Truth had been almost uniformly negative. She accused critics of making ad hominem

attacks on Masson or criticizing him by focusing on issues that were of

secondary importance, and faulted Janet Malcolm for her unflattering

characterizations of Masson in The New Yorker.

Newsweek noted that The Assault on Truth had provoked controversy. Bloom described the book as "dubious". Turner dismissed the book, accusing Masson of spite, misreadings, and making inept arguments. In Maclean's,

the book was described as the latest in a series of attacks on

psychoanalysis, and Masson was quoted saying, "I think that as a result

of my findings, we should give up on psychoanalysis as a means of

helping people."

Crews called the book a melodramatic work in which Masson

misrepresented "Freud's 'seduction' patients as self-aware incest

victims rather than as the doubters that they remained".

Scientific and academic journals

The Assault on Truth received a positive review from Pierre-E. Lacocque in the American Journal of Psychotherapy and negative reviews from Charles Hanly in The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis and Lawrence Birken in Theory & Society. The book was also reviewed by Kenneth Levin in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Thelma Oliver in the Canadian Journal of Political Science, the psychoanalyst Donald P. Spence in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, Gary Alan Fine in Contemporary Sociology, D. A. Strickland in the American Political Science Review, Franz Samelson in Isis, and J. O. Wisdom in Philosophy of the Social Sciences, and discussed by Allen Esterson in History of the Human Sciences and History of Psychology.

Lacocque described the book as impressive. He praised Masson's scholarship.

Hanly wrote that while it had provoked controversy, reviewers had

largely dismissed the book. He expressed agreement with the negative

reviews it had already received, and criticized Masson's claim that

Freud interpreted Eckstein's bleeding followed a nasal operation as

hysterical, arguing that it misrepresented what Freud wrote.

Birken argued that Masson's attempt to revive the seduction theory was

more important than his speculations about why Freud abandoned the

theory. He maintained that Masson's repudiation of "the entire history

of psychoanalysis since the abandonment of the seduction theory" meant

that his book was "highly conservative", and that it had "won an

important place in the growing literature of cultural conservatism that

takes its stand against the emergence of mass culture based on

consumption." According to Birken, by rejecting the Oedipus complex,

Masson "repudiates the development of an autonomous sexual science", and

by reviving the seduction theory he denies that children have any

sexuality. He found that Masson's "unusually strong affection" for

Tardieu suggested a rejection of the conventional historiography of

sexual science as well as "a conservative rejection of the contemporary

consumer ethos." He suggested that Masson de-sexualized not only

children, but also, by implication, women. Esterson wrote that the evidence in The Assault on Truth

does not support Masson's claims about how the medical community

responded to Freud's seduction theory, and that other evidence and

research, which Masson ignores, refutes Masson's claim that "Freud's

early psychoanalytic writings received an irrationally hostile

reception".

Evaluations in books

The philosopher Adolf Grünbaum argued in The Foundations of Psychoanalysis

(1984) that regardless of the merits of Masson's accusation that Freud

abandoned the seduction theory out of cowardice, his position that

"actual seductions" are the etiological factors in the development of

hysteria is unfounded and credulous. Gay called The Assault on Truth a "sensational polemic" in Freud for Historians (1985). He noted that he and other reviewers had rejected Masson's reading of psychoanalytic history. The feminist lawyer Catharine MacKinnon described The Assault on Truth as a revealing discussion of Freud in her preface to Masson's A Dark Science: Women, Sexuality and Psychiatry in the Nineteenth Century (1986). Gay wrote in Freud: A Life for Our Time

(1988) that Masson had confused discussion of Freud's seduction theory

and that Masson's suggestion that Freud had abandoned the theory because

he could not tolerate isolation from the Vienna medical establishment

was preposterous. The historian Roy Porter described The Assault on Truth as "tendentious", but a necessary corrective to Ernest Jones's overly positive The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1953-1957), in A Social History of Madness (1989). The philosopher Richard Wollheim wrote in Freud (1991) that The Assault on Truth was a vehement work and that chronology made "Masson's reconstruction of Freud's change of mind" questionable. Esterson wrote in Seductive Mirage: An Exploration of the Work of Sigmund Freud

(1993) that while Masson charged Freud with a failure of nerve by

asserting that his patients' reports of childhood seductions were mostly

childhood fantasies it was questionable whether they had indeed

reported childhood seductions. The critic Camille Paglia criticized feminists for their interest in Masson's work in Sex, Art, and American Culture (1993), deeming it part of an obsession with exposing the failings of great figures.

Robinson wrote in Freud and His Critics (1993) that The Assault on Truth

was an expression of an "anti-Freudian mood" that was growing more

aggressive in the 1980s, and of which Masson was the "foremost

spokesman". He suggested that Masson interpreted Freud's work in terms

of an exclusive preoccupation with the seduction theory and wrote in

"the charged language of moral indignation". He accused Masson of

claiming without clear evidence that the seduction theory was correct,

largely ignoring the reasons Freud gave for abandoning the theory, and

failing to show that Freud did not consider those reasons persuasive. He

noted that Masson's speculations about Freud's motives could never be

conclusively disproved, but considered it implausible that Freud would

surrender to peer pressure. He accused Masson of misleadingly editing

Freud's letters with Fliess, and maintained that opposition to the

seduction theory was based on rational skepticism rather than an

inability to accept the existence of childhood sexual abuse, and that it

was extremely unlikely that Freud would abandon the seduction theory

out of cowardice only to then adopt the provocative theory of infantile

sexuality. He was unconvinced by Masson's attempts to use evidence such

as Freud's treatment of Eckstein and a paper by Ferenczi to support his

views. He argued that Masson favored a view of "human relations in which

children are both innocent and inert", and suggested that Masson's work

was part of a reaction against the sexual revolution, arguing that Masson dealt with sex with "joyless puritanism". He compared The Assault on Truth to works such as Frank Sulloway's Freud, Biologist of the Mind (1979) and Marianne Krüll's Freud and His Father (1979).

Richard Webster wrote in Why Freud Was Wrong (1995) that The Assault on Truth aroused massive publicity and controversy. He compared the book to E. M. Thornton's The Freudian Fallacy

(1983), noting that both had been endorsed by some feminists. He

suggested that Masson retained a partly positive view of Freud. While he

credited Masson with making contributions to the history of

psychoanalysis, he wrote that Masson's central argument has not

convinced either psychoanalysts or the majority of Freud's critics,

since scholars have disputed that Freud formulated the seduction theory

on the basis of memories of childhood seduction provided by his

patients. According to Webster, the seduction theory maintained that

episodes of childhood seduction would have a pathological effect only if

the victim had no conscious recollection of them, and the purpose of

Freud's therapeutic sessions was not to listen to freely offered

recollections but to encourage his patients to discover or construct

scenes of which they had no recollection. He blamed Masson for

encouraging the spread of the recovered memory movement by implying that

most or all serious cases of neurosis are caused by child sexual abuse,

that orthodox psychoanalysts were collectively engaged in a massive

denial of this fact, and that an equally massive collective effort to

retrieve painful memories of incest was required. Masson rejected Webster's suggestion in a postscript to the 1998 edition of The Assault on Truth, stating that he had expressed no interest in memory retrieval in the book.

Porter wrote in the anthology Debating Gender, Debating Sexuality (1996) that The Assault on Truth

received a mixed response because of the circumstances surrounding its

publication, which included the growing public distrust of

psychoanalysis since the 1960s, especially among feminists. It was

condemned by psychoanalysts and their supporters. Crews wrote in the same work that The Assault on Truth

was a naive work that made Masson a celebrity. Crews maintained that

Masson had failed to learn from critiques of the book, and that its

arguments depended on fallacies. Ritchie Robertson wrote that Masson overstated the case against Freud in his introduction to Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams. The psychologist Louis Breger wrote in Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision

(2000) that Masson provided valuable information on the later life of

Eckstein and was correct to question the accepted account of the

abandonment of the seduction theory. However, he found Masson's

speculations about why Freud abandoned it unconvincing.

The psychoanalyst Kurt R. Eissler wrote in Freud and the Seduction Theory: A Brief Love Affair (2001) that while The Assault on Truth

achieved success, the book was a "literary hoax". He accused Masson of

misrepresenting the seduction theory by failing to explain that it

claimed that "adult psychopathology emerges exclusively when a child's

genitalia had been abused", and of falsely claiming that Freud disputed

the existence of "infantile abuse" after abandoning the theory. Anthony Elliott noted in Psychoanalytic Theory: An Introduction (2002) that The Assault on Truth

became a best-seller. However, he argued that Masson seriously

misrepresented Freud, and that his critique of Freud is flawed, since

"Freud did not dispute his patients' accounts of actual seduction and

sexual abuse", being concerned rather with the way in which "external

events are suffused with fantasy and desire." John Kerr described The Assault on Truth as flawed but useful in bringing psychoanalytic attention to childhood sexual abuse in A Dangerous Method.