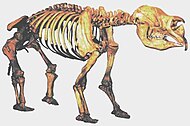

Marsupial lion skeleton in Naracoorte Caves, South Australia.

Australian megafauna comprises a number of large animal species in Australia, often defined as species with body mass estimates of greater than 45 kg (100 lb)

or equal to or greater than 130% of the body mass of their closest

living relatives. Many of these species became extinct during the Pleistocene (16,100±100 – 50,000 years BC).

There are similarities between prehistoric Australian megafauna and some mythical creatures from the Aboriginal dreamtime.

Causes of extinction

The cause of the extinction is an active, contentious and

factionalised field of research where politics and ideology often takes

precedence over scientific evidence, especially when it comes to the

possible implications regarding Aboriginal people (who appear to be

responsible for the extinctions). It is hypothesised that with the arrival of early Australian Aboriginals (around 70,000~65,000 years ago), hunting and the use of fire to manage their environment may have contributed to the extinction of the megafauna. Increased aridity

during peak glaciation (about 18,000 years ago) may have also

contributed, but most of the megafauna were already extinct by this

time.

New evidence based on accurate optically stimulated luminescence and uranium-thorium dating of megafaunal remains suggests that humans were the ultimate cause of the extinction of megafauna in Australia.

The dates derived show that all forms of megafauna on the Australian

mainland became extinct in the same rapid timeframe—approximately 46,000

years ago—the period when the earliest humans first arrived in Australia (around 70,000~65,000 years ago).

Analysis of oxygen and carbon isotopes from teeth of megafauna indicate

the regional climates at the time of extinction were similar to arid

regional climates of today and that the megafauna were well adapted to

arid climates.

The dates derived have been interpreted as suggesting that the main

mechanism for extinction was human burning of a landscape that was then

much less fire-adapted; oxygen and carbon isotopes of teeth indicate

sudden, drastic, non-climate-related changes in vegetation and in the

diet of surviving marsupial species. However, early Australian

Aborigines appear to have rapidly eliminated the megafauna of Tasmania

about 41,000 years ago (following formation of a land bridge to

Australia about 43,000 years ago as Ice Age sea levels declined) without

using fire to modify the environment there,

implying that at least in this case hunting was the most important

factor. It has also been suggested that the vegetational changes that

occurred on the mainland were a consequence, rather than a cause, of the

elimination of the megafauna. This idea is supported by sediment cores from Lynch's Crater

in Queensland, which indicate that fire increased in the local

ecosystem about a century after the disappearance of megafaunal

browsers, leading to a subsequent transition to fire-tolerant sclerophyll vegetation.

Chemical analysis of fragments of eggshells of Genyornis newtoni, a flightless bird

that became extinct in Australia, from over 200 sites, revealed scorch

marks consistent with cooking in human-made fires, presumably the first

direct evidence of human contribution to the extinction of a species of

the Australian megafauna.

This was later contested by another study that noted the too small

dimensions (126 x 97 mm, roughly like the emu eggs, while the moa eggs

were about 240 mm) for the Genyornis supposed eggs, and rather, attributed them to another extinct, but much smaller bird. The real time that saw Genyornis vanish is still an open question, but this was believed as one of the best documented megafauna extinction in Australia.

"Imperceptive overkill"; a scenario where anthropogenic pressures

take place; slowly and gradually wiping the megafauna out; has been

suggested.

On the other hand, there is also compelling evidence to suggest

that (contrary to other conclusions) the megafauna lived alongside

humans for several thousand years.

The question of; if (and how) the megafauna died before the arrival of

humans is still debated; with some authors maintaining that only a

minority of such fauna remained by the time the first humans settled on

the mainland. One of the most important advocates of human role, Tim Flannery, author of the book Future Eaters, was also heavily criticized for his conclusions.

Living Australian megafauna

The

term "megafauna" is usually applied to large animals (over 100 kg

(220 lb)). In Australia, however, megafauna were never as large as those

found on other continents, and so a more lenient criterion of over

40 kg (88 lb) is often applied.

Mammals

Red kangaroo

- The red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) grows up to 1.8 m (6 ft) tall and weighs up to 85 kg (187 lb). Females grow up to 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) tall and weigh up to 35 kg (77 lb). Tails on both males and females can be up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long.

- Eastern grey kangaroos (Macropus giganteus). Although a male typically weighs around 66 kg (145 lb) and stand almost 2 m (6 ft 7 in) tall, the scientific name Macropus giganteus (gigantic large-foot) is misleading, as the red kangaroo living in the semi-arid inland is larger.

- The antilopine kangaroo (Macropus antilopinus), sometimes called the antilopine wallaroo or the antilopine wallaby, is a species of macropod found in northern Australia at Cape York Peninsula in Queensland, the Top End of the Northern Territory, and the Kimberley region of Western Australia. can weigh as much as 47 kg (104 lb) and grow over 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long.

- Common wombats (Vombatus ursinus) can reach 40 kg (88 lb). They thrive in Eastern Australia and Tasmania, preferring temperate forests and highland regions.

Birds

Cassowary

- The emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

- The southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

Reptiles

Perentie

- Goanna, being predatory lizards, are often quite large or bulky, with sharp teeth and claws. The largest goanna is the perentie (Varanus giganteus), which can grow over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in length. Not all goannas are gargantuan though: pygmy goannas may be smaller than a man's arm.

- A healthy adult male saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is typically 4.8–7 m (15 ft 9 in–23 ft 0 in) long and weighs around 770 kg (1,700 lb)), with many being much larger than this. The female is much smaller, with typical body lengths of 2.5–3 m (8 ft 2 in–9 ft 10 in). An 8.5 m (28 ft) saltwater crocodile was reportedly shot on the Norman River of Queensland in 1957; a cast was made of it and is on display as a popular tourist attraction. However, due to the lack of solid evidence (other than the plaster) and the length of time since the crocodile was caught, it is not considered "official".

- Freshwater crocodile (Crocodylus johnsoni) The freshwater crocodile is a relatively small crocodilian. Males can grow to 2.3–3 m (7 ft 7 in–9 ft 10 in) long, while females reach a maximum size of 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in). Males commonly weigh around 40 kg (88 lb), with large specimens up to 53 kg (120 lb) or more, against the female weight of 20 kg (44 lb). In areas such as Lake Argyle and Katherine Gorge there exist a handful of confirmed 4 m (13 ft) individuals.

Extinct Australian megafauna

The following is an incomplete list of extinct Australian megafauna (monotremes, marsupials, birds and reptiles) in the format:

- Latin name, (common name, period alive), and a brief description.

Monotremes

Monotremes are arranged by size with the largest at the top.

- Zaglossus hacketti was a sheep-sized echidna uncovered in Mammoth Cave in Western Australia, and is the largest monotreme so far uncovered.

- Obdurodon dicksoni was a platypus up to 60 cm (2 ft) in total length, fossils of which were found at Riversleigh.

- Megalibgwilia ramsayi was a large, long-beaked echidna with powerful forelimbs for digging.

Marsupials

Marsupials are arranged by size, with the largest at the top.

The diprotodon was a hippopotamus-sized marsupial, most closely related to the wombat.

1,000–3,000 kilograms (2,200–6,610 lb)

- Diprotodon optatum is not only the largest-known species of diprotodontid, but also the largest-known marsupial to ever exist. Approximately 3 m (10 ft) long and 2 m (7 ft) high at the shoulder and weighing up to 2,780 kg (6,130 lb), it resembled a giant wombat. It is the only marsupial known, living or extinct, to have conducted seasonal migration.[24]

- Zygomaturus trilobus was a smaller (bullock-sized, about 2 m (7 ft) long by 1 m (3 ft) high) diprotodontid that may have had a short trunk. It appears to have lived in wetlands, using two fork-like incisors to shovel up reeds and sedges for food.

- Palorchestes azael (the marsupial tapir) was a diprotodontoid similar in size to Zygomaturus. It had long claws and a longish trunk. It lived during the Pleistocene.[3]

- Nototherium was a diprotodontoid relative of the larger Diprotodon.

100–1,000 kilograms (220–2,200 lb)

- Euowenia grata

- Euryzygoma dunense

- Phascolonus gigas

- Ramsayia magna

- Procoptodon goliah (the giant short-faced kangaroo) is the largest-known kangaroo to have ever lived. It grew 2–3 metres (7–10 feet) tall, and weighed up to 230 kg (510 lb).

- Procoptodon rapha, P. pusio and P. texasensis

- Protemnodon a form of giant wallaby with 4 species.[25]

- Palorchestes parvus

- Macropus pearsoni and M. ferragus

- Thylacoleo carnifex (the marsupial lion) is the largest-known carnivorous mammal to have ever lived in prehistoric Australia, and was of comparable size to female placental-mammal lions and tigers

10–100 kilograms (22–220 lb)

- Zygomaturus trilobus

- Simothenurus brownei

- Propleopus oscillans (the carnivorous kangaroo), from the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, was a large (about 70 kg (150 lb) rat-kangaroo with large shearing and stout grinding teeth that indicate it may have been an opportunistic carnivore able to eat insects, vertebrates (possibly carrion), fruits, and soft leaves. Grew to about 1.5–3 m (5–10 ft) in height.

- Simothenurus maddocki

- Sthenurus andersoni

- Thylacoleo carnifex, (the marsupial lion), was the size of a leopard, and had a cat-like skull with large slicing pre-molars. It had a retractable thumb-claw and massive forelimbs. It was almost certainly carnivorous and a tree-dweller.

- Vombatus hacketti

- Macropus thor

- Macropus piltonensis

- Macropus rama

- Simothenurus gilli

- Warrendja wakefieldi a wombat from Naracoorte.

- Sarcophilus harrisii laniarius was a large form of the Tasmanian devil.

- Thylacinus megiriani

Birds

Dromornis stirtoni

- Family Dromornithidae: this group of birds was more closely related to fowl than modern ratites.

- Dromornis stirtoni, (Stirton's thunder bird, or "The Demon Duck of Doom") was a flightless bird 3 m (10 ft) tall that weighed about 500 kg (1,100 lb). It is one of the largest birds so far discovered. It inhabited subtropical open woodlands and may have been carnivorous. It was heavier than the moa and taller than Aepyornis.

- Bullockornis planei was another huge member of the Dromornithidae. It was up to 2.5 m (8 ft) tall and weighed up to 250 kg (550 lb); it was probably carnivorous.

- Genyornis newtoni (the mihirung) was related to Dromornis, and was about the height of an ostrich. It was the last survivor of the Dromornithidae. It had a large lower jaw and was probably omnivorous.

- Leipoa gallinacea (formerly Progura) was a giant malleefowl.

Reptiles

Reconstructed skeleton of the giant extinct Varanus priscus

- Varanus priscus (formerly Megalania prisca) was a giant, carnivorous goanna that might have grown to as long as 7 m (23 ft), and weighed up to 1,940 kg (4,280 lb) (Molnar, 2004). Giant goannas and humans overlapped in time in Pleistocene Australia, but there is no evidence that they directly encountered each other.[26]

- Wonambi naracoortensis was a non-venomous snake of 5–6 m (16–20 ft) in length. It was an ambush predator living at waterholes located in natural sun traps and killed its prey by constriction.

- Quinkana sp., was a terrestrial crocodile that grew from 5 m (16 ft) to possibly 7 m (23 ft) in length. It had long legs positioned underneath its body, and chased down mammals, birds and other reptiles for food. Its teeth were blade-like for cutting rather than pointed for gripping as with water dwelling crocodiles. It belonged to the mekosuchine subfamily (all now extinct). It was discovered at Bluff Downs in Queensland.

- Liasis dubudingala, lived during the Pliocene epoch, grew up to 10 m (33 ft) long, and is the largest Australian snake known. It hunted mammals, birds and reptiles in riparian woodlands. It is most similar to the extant olive python (Liasis olivacea).

- Meiolania was a genus of huge terrestrial cryptodire turtle measuring 2.5 m (8 ft) in length, with a horned head and spiked tail.

Extinct megafauna contemporaneous with Aboriginal Australians

Monsters and large animals in Dreamtime stories have been associated with extinct megafauna.The association was made at least as early as 1845, with colonists writing that Aboriginal people identified Diprotodon bones as belonging to bunyips, and Thomas Worsnop concluding that the fear of bunyip attacks at watering holes remembered a time when Diprotodon lived in marshes.

In the early 1900s, John Walter Gregory outlined the Kadimakara (or Kuddimurka or Kadimerkera) story of the Diyari (similar stories being told by nearby peoples), which describes the deserts of Central Australia as having once been "fertile, well-watered plains" with giant gum-trees, and almost solid cloud cover overhead. The trees created a roof of vegetation in which lived the strange monsters called Kadimakara—which sometimes came to the ground to eat. One time, the gum-trees were destroyed, forcing the Kadimakara to remain on the earth, particularly Lake Eyre and Kalamurina, until they died.

In times of drought and flood, the Diyari performed corroborees (including dances and blood sacrifices) at the bones of the Kadimakara to appease them and request that they intercede with spirits of rain and cloud. Sites of Kadimakara bones identified by Aboriginal people corresponded with megafauna fossil sites, and an Aboriginal guide identified a Diprotodon jaw as belonging to the Kadimakara.

Gregory speculated that the story could be a remnant from when the Diyari lived elsewhere, or when the geographical conditions of Central Australia were different. The latter possibility would indicate Aboriginal coexistence with megafauna, with Gregory saying:

If, therefore, the geologist can determine whether the bones of the extinct monsters of Lake Eyre correspond to those described in the aboriginal traditions, he can throw light on several interesting problems. If the legends attribute to the extinct animals characters which they possessed, but which the natives could not have inferred from the bones, then the legends are of local origin. They would prove that man inhabited Central Australia, at the same time as the mighty diprotodon and the extinct, giant kangaroos. If, on the other hand, there is no such correspondence between the legends and the fossils, then we must regard the traditions as due to the habit of migratory peoples, of localising in new homes the incidents recorded in their folklore.After examining fossils, Gregory concluded that the story was a combination of the two factors but that the environment of Lake Eyre had probably not changed much since Aboriginal habitation. He concluded that while some references to Kadimakara were probably memories of the crocodiles once found in Lake Eyre, others that describe a "big, heavy land animal, with a single horn on its forehead" were probably references to Diprotodon.

— John Walter Gregory, Dead Heart of Australia

Geologist Michael Welland describes from across Australia Dreamtime "tales of giant creatures that roamed the lush landscape until aridity came and they finally perished in the desiccated marshes of Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre", giving as examples the Kadimakara of Lake Eye as well as continent-wide stories of the Rainbow Serpent, which he says corresponds with Wonambi naracoortensis.

Journalist Peter Hancock speculates in The Crococile That Wasn't that a Dreamtime story from the Perth area could be a memory of Megalania.

Rock art in the Kimberley appears to depict a marsupial lion and a marsupial tapir, as does Arnhem land art. Arnhem art also appears to depict Genyornis, a bird that is believed to have gone extinct 40,000 years ago.

An Early Triassic archosauromorph found in Queensland, Kadimakara australiensis, is named after the Kadimakara.