Fossil of Microraptor gui includes impressions of feathered wings (see arrows)

Since scientific research began on dinosaurs in the early 1800s, they were generally believed to be closely related to modern reptiles, such as lizards. The word "dinosaur" itself, coined in 1842 by paleontologist Richard Owen, comes from the Greek for "fearsome lizard". This view began to shift during the so-called dinosaur renaissance

in scientific research in the late 1960s, and by the mid-1990s

significant evidence had emerged that dinosaurs were much more closely

related to birds, which descended directly from the theropod group of dinosaurs and are themselves a subgroup within the Dinosauria.

Knowledge of the origin of feathers developed as new fossils were

discovered throughout the 2000s and 2010s and as technology enabled

scientists to study fossils more closely. Among non-avian dinosaurs, feathers or feather-like integument have been discovered in dozens of genera via direct and indirect fossil evidence. Although the vast majority of feather discoveries have been in coelurosaurian theropods, feather-like integument has also been discovered in at least three ornithischians, suggesting that feathers may have been present on the last common ancestor of the Ornithoscelida, a dinosaur group including both theropods and ornithischians. It is possible that feathers first developed in even earlier archosaurs, in light of the discovery of highly feather-like pycnofibers in pterosaurs. Crocodilians also possess beta keratin similar to those of birds, which suggests that they evolved from common ancestral genes.

History of research

Early

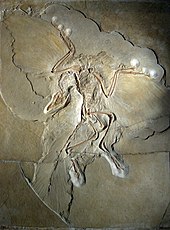

The Berlin Archaeopteryx

Shortly after the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, British biologist Thomas Henry Huxley proposed that birds were descendants of dinosaurs. He compared the skeletal structure of Compsognathus, a small theropod dinosaur, and the 'first bird' Archaeopteryx lithographica (both of which were found in the Upper Jurassic Bavarian limestone of Solnhofen). He showed that, apart from its hands and feathers, Archaeopteryx was quite similar to Compsognathus. Thus Archaeopteryx represents a transitional fossil. In 1868 he published On the Animals which are most nearly intermediate between Birds and Reptiles, making the case. The first restoration of a feathered dinosaur was Thomas Henry Huxley's depiction in 1876 of a feathered Compsognathus

to accompany a lecture on the evolution of birds he delivered in New

York in which he speculated that the aforementioned dinosaur might have

been in possession of feathers. The leading dinosaur expert of the time, Richard Owen, disagreed, claiming Archaeopteryx as the first bird outside dinosaur lineage. For the next century, claims that birds were dinosaur descendants faded, with more popular bird-ancestry hypotheses including 'crocodylomorph' and 'thecodont' ancestors, rather than dinosaurs or other archosaurs.

'Dinosaur renaissance'

In 1969, John Ostrom described Deinonychus antirrhopus, a theropod

that he had discovered in Montana in 1964 and whose skeletal

resemblance to birds seemed unmistakable. Ostrom became a leading

proponent of the theory that birds are direct descendants of dinosaurs.

Further comparisons of bird and dinosaur skeletons, as well as cladistic analysis strengthened the case for the link, particularly for a branch of theropods called maniraptors. Skeletal similarities include the neck, the pubis, the wrists (semi-lunate carpal), the 'arms' and pectoral girdle, the shoulder blade, the clavicle and the breast bone. In all, over a hundred distinct anatomical features are shared by birds and theropod dinosaurs.

Other researchers drew on these shared features and other aspects of

dinosaur biology and began to suggest that at least some theropod

dinosaurs were feathered.

At the same time, paleoartists began to create modern restorations of highly active dinosaurs. In 1969, Robert T. Bakker drew a running Deinonychus. His student Gregory S. Paul depicted non-avian maniraptoran

dinosaurs with feathers and protofeathers, starting in the late 1970s.

In 1975, Eleanor M. Kish began to paint accurate images of dinosaurs,

her Hypacrosaurus being the first one shown with its camouflage.

Before the discovery of feathered dinosaur fossils, the evidence was limited to Huxley and Ostrom's comparative anatomy. Some mainstream ornithologists, including Smithsonian Institution curator Storrs L. Olson, disputed the links, specifically citing the lack of fossil evidence for feathered dinosaurs.

By the 1990s, however, most paleontologists considered birds to be

surviving dinosaurs and referred to 'non-avian dinosaurs' (all extinct),

to distinguish them from birds (Avialae).

Fossil discoveries

One of the earliest discoveries of possible feather impressions by non-avian dinosaurs is an ichnofossil (Fulicopus lyellii) of the 195-199 million year old Portland Formation

in the northeastern United States. Gierlinski (1996, 1997, 1998) and

Kondrat (2004) have interpreted traces between two footprints in this

fossil as feather impressions from the belly of a squatting dilophosaurid. Although some reviewers have raised questions about the naming and interpretation of this fossil, if correct, this early Jurassic fossil is the oldest known evidence of feathers, almost 30 million years older than the next-oldest-known evidence.

Sinosauropteryx fossil, the first fossil of a definitively non-avialan dinosaur with feathers

After a century of hypotheses without conclusive evidence,

well-preserved fossils of feathered dinosaurs were discovered during the

1990s, and more continue to be found. The fossils were preserved in a Lagerstätte—a sedimentary deposit exhibiting remarkable richness and completeness in its fossils—in Liaoning, China. The area had repeatedly been smothered in volcanic ash produced by eruptions in Inner Mongolia 124 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous

epoch. The fine-grained ash preserved the living organisms that it

buried in fine detail. The area was teeming with life, with millions of

leaves, angiosperms (the oldest known), insects, fish, frogs, salamanders, mammals, turtles, and lizards discovered to date.

The most important discoveries at Liaoning have been a host of

feathered dinosaur fossils, with a steady stream of new finds filling in

the picture of the dinosaur–bird connection and adding more to theories

of the evolutionary development of feathers and flight. Turner et al. (2007) reported quill knobs from an ulna of Velociraptor mongoliensis, and these are strongly correlated with large and well-developed secondary feathers.

Behavioural evidence, in the form of an oviraptorosaur on its nest, showed another link with birds. Its forearms were folded, like those of a bird. Although no feathers were preserved, it is likely that these would have been present to insulate eggs and juveniles.

Not all of the Chinese fossil discoveries proved valid however.

In 1999, a supposed fossil of an apparently feathered dinosaur named Archaeoraptor liaoningensis, found in Liaoning Province,

northeastern China, turned out to be a forgery. Comparing the

photograph of the specimen with another find, Chinese paleontologist Xu Xing came to the conclusion that it was composed of two portions of different fossil animals. His claim made National Geographic review their research and they too came to the same conclusion. The bottom portion of the "Archaeoraptor" composite came from a legitimate feathered dromaeosaurid now known as Microraptor, and the upper portion from a previously known primitive bird called Yanornis.

In 2011, samples of amber were discovered to contain preserved feathers from 75 to 80 million years ago during the Cretaceous

era, with evidence that they were from both dinosaurs and birds.

Initial analysis suggests that some of the feathers were used for

insulation, and not flight.

More complex feathers were revealed to have variations in coloration

similar to modern birds, while simpler protofeathers were predominantly

dark. Only 11 specimens are currently known. The specimens are too rare

to be broken open to study their melanosomes, but there are plans for using non-destructive high-resolution X-ray imaging.

In 2016, the discovery was announced of a feathered dinosaur tail

preserved in amber that is estimated to be 99 million years old. Lida

Xing, a researcher from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, found the specimen at an amber market in Myanmar. It is the first definitive discovery of dinosaur material in amber.

In March 2018, scientists reported that Archaeopteryx was likely capable of flight, but in a manner substantially different from that of modern birds.

Current knowledge

Non-avian dinosaur species preserved with evidence of feathers

Fossil of Sinornithosaurus millenii, the first evidence of feathers in dromaeosaurids

Cast of a Caudipteryx fossil with feather impressions and stomach content

Fossil cast of a Sinornithosaurus millenii

Jinfengopteryx elegans fossil

Several non-avian dinosaurs are now known to have been feathered. Direct evidence of feathers exists for several species.

In all examples, the evidence described consists of feather

impressions, except those genera inferred to have had feathers based on

skeletal or chemical evidence, such as the presence of quill knobs (the

anchor points for wing feathers on the forelimb) or a pygostyle (the fused vertebrae at the tail tip which often supports large feathers).

Primitive feather types

Integumentary

structures that gave rise to the feathers of birds are seen in the

dorsal spines of reptiles and fish. A similar stage in their evolution

to the complex coats of birds and mammals can be observed in living

reptiles such as iguanas and Gonocephalus

agamids. Feather structures are thought to have proceeded from simple

hollow filaments through several stages of increasing complexity, ending

with the large, deeply rooted feathers with strong pens (rachis), barbs and barbules that birds display today.

According to Prum's (1999) proposed model, at stage I, the

follicle originates with a cylindrical epidermal depression around the

base of the feather papilla. The first feather resulted when

undifferentiated tubular follicle collar developed out of the old

keratinocytes being pushed out. At stage II, the inner, basilar layer of

the follicle collar differentiated into longitudinal barb ridges with

unbranched keratin filaments, while the thin peripheral layer of the

collar became the deciduous sheath, forming a tuft of unbranched barbs

with a basal calamus. Stage III consists of two developmental novelties,

IIIa and IIIb, as either could have occurred first. Stage IIIa involves

helical displacement of barb ridges arising within the collar. The barb

ridges on the anterior midline of the follicle fuse together, forming

the rachis. The creation of a posterior barb locus follows, giving an

indeterminate number of barbs. This resulted in a feather with a

symmetrical, primarily branched structure with a rachis and unbranched

barbs. In stage IIIb, barbules paired within the peripheral barbule

plates of the barb ridges, create branched barbs with rami and barbules.

This resulting feather is one with a tuft of branched barbs without a

rachis. At stage IV, differentiated distal and proximal barbules produce

a closed, pennaceous vane. A closed vane develops when pennulae on the

distal barbules form a hooked shape to attach to the simpler proximal

barbules of the adjacent barb. Stage V developmental novelties gave rise

to additional structural diversity in the closed pennaceous feather.

Here, asymmetrical flight feathers, bipinnate plumulaceous feathers,

filoplumes, powder down, and bristles evolved.

Some evidence suggests that the original function of simple

feathers was insulation. In particular, preserved patches of skin in

large, derived, tyrannosauroids show scutes,

while those in smaller, more primitive, forms show feathers. This may

indicate that the larger forms had complex skins, with both scutes and

filaments, or that tyrannosauroids may be like rhinos and elephants, having filaments at birth and then losing them as they developed to maturity. An adult Tyrannosaurus rex weighed about as much as an African elephant. If large tyrannosauroids were endotherms, they would have needed to radiate heat efficiently. However, due to the different structural properties of feathers compared to fur, as well as a larger surface area per cubic square meter, it is extremely unlikely even the largest theropods would suffer overheating issues from an extensive feather coat.

There is an increasing body of evidence that supports the display

hypothesis, which states that early feathers were colored and increased

reproductive success.

Coloration could have provided the original adaptation of feathers,

implying that all later functions of feathers, such as thermoregulation

and flight, were co-opted. This hypothesis has been supported by the discovery of pigmented feathers in multiple species.

Supporting the display hypothesis is the fact that fossil feathers have

been observed in a ground-dwelling herbivorous dinosaur clade, making

it unlikely that feathers functioned as predatory tools or as a means of

flight. Additionally, some specimens have iridescent feathers.

Pigmented and iridescent feathers may have provided greater

attractiveness to mates, providing enhanced reproductive success when

compared to non-colored feathers. Current research shows that it is

plausible that theropods would have had the visual acuity necessary to

see the displays. In a study by Stevens (2006), the binocular field of

view for Velociraptor has been estimated to be 55 to 60 degrees, which is about that of modern owls. Visual acuity for Tyrannosaurus has been predicted to be anywhere from about that of humans to 13 times that of humans. However, as both Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus

have a rather extended evolutionary relationship with the more basal

theropods, it is unclear how much of this visual acuity data can be

extrapolated.

The idea that precursors of feathers appeared before they were

co-opted for insulation is already stated in Gould and Vrba, 1982.

The original benefit might have been metabolic. Feathers are largely

made of the keratin protein complex, which has disulfide bonds between

amino acids that give it stability and elasticity. The metabolism of

amino acids containing sulfur can be toxic; however, if the sulfur amino

acids are not catabolized at the final products of urea or uric acid

but used for the synthesis of keratin instead, the release of hydrogen

sulfide is extremely reduced or avoided. For an organism whose

metabolism works at high internal temperatures of 40 °C or greater, it

can be extremely important to prevent the excess production of hydrogen

sulfide. This hypothesis could be consistent with the need for high

metabolic rate of theropod dinosaurs.

It is not known with certainty at what point in archosaur phylogeny

the earliest simple "protofeathers" arose, or whether they arose once

or independently multiple times. Filamentous structures are clearly

present in pterosaurs, and long, hollow quills have been reported in specimens of the ornithischian dinosaurs Psittacosaurus and Tianyulong. In 2009, Xu et al. noted that the hollow, unbranched, stiff integumentary structures found on a specimen of Beipiaosaurus were strikingly similar to the integumentary structures of Psittacosaurus and pterosaurs. They suggested that all of these structures may have been inherited from a common ancestor much earlier in the evolution of archosaurs, possibly in an ornithodire from the Middle Triassic or earlier. More recently, findings in Russia of the basal neornithischian Kulindadromeus

report that although the lower leg and tail seemed to be scaled,

"varied integumentary structures were found directly associated with

skeletal elements, supporting the hypothesis that simple filamentous

feathers, as well as compound feather-like structures comparable to

those in theropods, were widespread amongst the whole dinosaur clade."

Display feathers are also known from dinosaurs that are very primitive members of the bird lineage, or Avialae. The most primitive example is Epidexipteryx,

which had a short tail with extremely long, ribbon-like feathers. Oddly

enough, the fossil does not preserve wing feathers, suggesting that Epidexipteryx was either secondarily flightless, or that display feathers evolved before flight feathers in the bird lineage. Plumaceous feathers are found in nearly all lineages of Theropoda common in the northern hemisphere, and pennaceous feathers are attested as far down the tree as the Ornithomimosauria. The fact that only adult Ornithomimus had wing-like structures suggests that pennaceous feathers evolved for mating displays.

Phylogeny and the inference of feathers in other dinosaurs

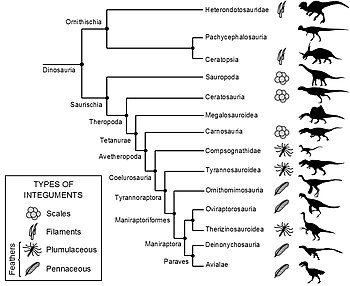

Cladogram showing distribution of feathers in Dinosauria, as of 2015

Fossil feather impressions are extremely rare and they require

exceptional preservation conditions to form. Therefore, only a few

non-avian feathered dinosaur genera

have been identified. All fossil feather specimens have been found to

show certain similarities. Due to these similarities and through

developmental research, many scientists believe that feathers have only

evolved once in dinosaurs.

Feathers would then have been passed down to all later, more derived

species, unless some lineages lost feathers secondarily. If a dinosaur

falls at a point on an evolutionary tree within the known

feather-bearing lineages, then its ancestors had feathers, and it is

quite possible that it did as well. This technique, called phylogenetic bracketing,

can also be used to infer the type of feathers a species may have had,

since the developmental history of feathers is now reasonably

well-known. All feathered species had filamentaceous or plumaceous

(downy) feathers, with pennaceous feathers found among the more

bird-like groups. The following cladogram is adapted from Godefroit et al., 2013.

Phylogenetic bracketing can also be used to evidence the lack of

feathered integument by inference. For example, the presence of scaly

integument in a specific clade would be a strong indicator that members

in the clade would share similar integument, as independent evolution of

feathers multiple times is unlikely, regardless if fossil evidence is

present for all genera within the clade.

Grey denotes a clade that is not

known to contain any feathered specimen at the time of writing, some of

which have fossil evidence of scales. The presence or lack of feathered

specimens in a given clade does not confirm that all members in a clade

have the specified integument, unless corroborated with representative

fossil evidence within clade members.