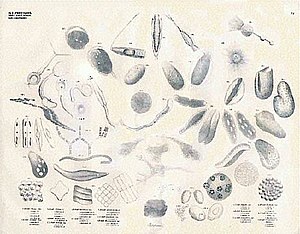

Clockwise from top left: Blepharisma japonicum, a ciliate; Giardia muris, a parasitic flagellate; Centropyxis aculeata, a testate (shelled) amoeba; Peridinium willei, a dinoflagellate; Chaos carolinense, a naked amoebozoan; Desmerella moniliformis, a choanoflagellate

Protozoa (also protozoan, plural protozoans) is an informal term for single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, which feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Historically, the protozoa were regarded as "one-celled animals", because they often possess animal-like behaviors, such as motility and predation, and lack a cell wall, as found in plants and many algae.

Although the traditional practice of grouping protozoa with animals is

no longer considered valid, the term continues to be used in a loose

way to identify single-celled organisms that can move independently and

feed by heterotrophy.

In some systems of biological classification, Protozoa is a high-level taxonomic group. When first introduced in 1818, Protozoa was erected as a taxonomic class, but in later classification schemes it was elevated to a variety of higher ranks, including phylum, subkingdom and kingdom. In a series of classifications proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith and his collaborators since 1981, Protozoa has been ranked as a kingdom. The seven-kingdom scheme presented by Ruggiero et al. in 2015, places eight phyla under Kingdom Protozoa: Euglenozoa, Amoebozoa, Metamonada, Choanozoa sensu Cavalier-Smith, Loukozoa, Percolozoa, Microsporidia and Sulcozoa.

Notably, this kingdom excludes several major groups of organisms

traditionally placed among the protozoa, including the ciliates, dinoflagellates, foraminifera, and the parasitic apicomplexans, all of which are classified under Kingdom Chromista. Kingdom Protozoa, as defined in this scheme, does not form a natural group or clade, but a paraphyletic group or evolutionary grade, within which the members of Fungi, Animalia and Chromista are thought to have evolved.

History

Class Protozoa, order Infusoria, family Monades by Georg August Goldfuss, c. 1844

The word "protozoa" (singular protozoon or protozoan) was coined in 1818 by zoologist Georg August Goldfuss, as the Greek equivalent of the German Urthiere, meaning "primitive, or original animals" (ur- ‘proto-’ + Thier ‘animal’). Goldfuss created Protozoa as a class containing what he believed to be the simplest animals. Originally, the group included not only single-celled microorganisms but also some "lower" multicellular animals, such as rotifers, corals, sponges, jellyfish, bryozoa and polychaete worms. The term Protozoa is formed from the Greek words πρῶτος (prôtos), meaning "first", and ζῶα (zôa), plural of ζῶον (zôon), meaning "animal". The use of Protozoa as a formal taxon has been discouraged by some researchers, mainly because the term implies kinship with animals (Metazoa) and promotes an arbitrary separation of "animal-like" from "plant-like" organisms.

In 1848, as a result of advancements in cell theory pioneered by Theodor Schwann and Matthias Schleiden, the anatomist and zoologist C. T. von Siebold proposed that the bodies of protozoans such as ciliates and amoebae consisted of single cells, similar to those from which the multicellular tissues of plants and animals were constructed. Von Siebold redefined Protozoa to include only such unicellular forms, to the exclusion of all metazoa (animals). At the same time, he raised the group to the level of a phylum containing two broad classes of microorganisms: Infusoria (mostly ciliates and flagellated algae), and Rhizopoda (amoeboid organisms). The definition of Protozoa as a phylum or sub-kingdom composed of "unicellular animals" was adopted by the zoologist Otto Bütschli—celebrated at his centenary as the "architect of protozoology"—and the term came into wide use.

John Hogg's

illustration of the Four Kingdoms of Nature, showing "Primigenal" as a

greenish haze at the base of the Animals and Plants, 1860

As a phylum under Animalia, the Protozoa were firmly rooted in the

old "two-kingdom" classification of life, according to which all living

beings were classified as either animals or plants. As long as this

scheme remained dominant, the protozoa were understood to be animals and

studied in departments of Zoology, while photosynthetic microorganisms

and microscopic fungi—the so-called Protophyta—were assigned to the

Plants, and studied in departments of Botany.

Criticism of this system began in the latter half of the 19th

century, with the realization that many organisms met the criteria for

inclusion among both plants and animals. For example, the algae Euglena and Dinobryon have chloroplasts for photosynthesis, but can also feed on organic matter and are motile. In 1860, John Hogg

argued against the use of "protozoa", on the grounds that "naturalists

are divided in opinion—and probably some will ever continue so—whether

many of these organisms, or living beings, are animals or plants."

As an alternative, he proposed a new kingdom called Primigenum,

consisting of both the protozoa and unicellular algae (protophyta),

which he combined together under the name "Protoctista". In Hoggs's

conception, the animal and plant kingdoms were likened to two great

"pyramids" blending at their bases in the Kingdom Primigenum.

Six years later, Ernst Haeckel also proposed a third kingdom of life, which he named Protista.

At first, Haeckel included a few multicellular organisms in this

kingdom, but in later work he restricted the Protista to single-celled

organisms, or simple colonies whose individual cells are not

differentiated into different kinds of tissues.

Despite these proposals, Protozoa emerged as the preferred taxonomic placement for heterotrophic

microorganisms such as amoebae and ciliates, and remained so for more

than a century. In the course of the 20th century, however, the old "two

kingdom" system began to weaken, with the growing awareness that fungi

did not belong among the plants, and that most of the unicellular

protozoa were no more closely related to the animals than they were to

the plants. By mid-century, some biologists, such as Herbert Copeland, Robert H. Whittaker and Lynn Margulis,

advocated the revival of Haeckel's Protista or Hogg's Protoctista as a

kingdom-level eukaryotic group, alongside Plants, Animals and Fungi.[18] A variety of multi-kingdom systems were proposed, and Kingdoms Protista and Protoctista became well established in biology texts and curricula.

While many taxonomists have abandoned Protozoa as a high-level

group, Thomas Cavalier-Smith has retained it as a kingdom in the various

classifications he has proposed. As of 2015, Cavalier-Smith's Protozoa

excludes several major groups of organisms traditionally placed among

the protozoa, including the ciliates, dinoflagellates and foraminifera (all members of the SAR supergroup). In its current form, his kingdom Protozoa is a paraphyletic

group which includes a common ancestor and most of its descendants, but

excludes two important clades that branch within it: the animals and

fungi.

Since the protozoa, as traditionally defined, can no longer be

regarded as "primitive animals" the terms "protists", "Protista" or

"Protoctista" are sometimes preferred. In 2005, members of the Society

of Protozoologists voted to change its name to the International Society of Protistologists.

Characteristics

Size

Protozoa, as traditionally defined, range in size from as little as 1 micrometre to several millimetres, or more. Among the largest are the deep-sea–dwelling xenophyophores, single-celled foraminifera whose shells can reach 20 cm in diameter.

The ciliate Spirostomum ambiguum can attain 3 mm in length

| Species | Cell type | Size in micrometres |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium falciparum | malaria parasite, trophozoite phase | 1-2 |

| Massisteria voersi | free-living cercozoan amoeboid | 2.3–3 |

| Bodo saltans | free living kinetoplastid flagellate | 5-8 |

| Plasmodium falciparum | malaria parasite, gametocyte phase | 7-14 |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | parasitic kinetoplastid, Chagas disease | 14-24 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | parasitic amoebozoan | 15–60 |

| Balantidium coli | parasitic ciliate | 50-100 |

| Paramecium caudatum | free-living ciliate | 120-330 |

| Amoeba proteus | free-living amoebozoan | 220–760 |

| Noctiluca scintillans | free-living dinoflagellate | 700–2000 |

| Syringammina fragilissima | foraminiferan amoeboid | up to 200000 |

Habitat

Free-living

protozoans are common and often abundant in fresh, brackish and salt

water, as well as other moist environments, such as soils and mosses.

Some species thrive in extreme environments such as hot springs and hypersaline lakes and lagoons. All protozoa require a moist habitat; however, some can survive for long periods of time in dry environments, by forming resting cysts which enable them to remain dormant until conditions improve.

Parasitic and symbiotic protozoa live on or within other organisms, including vertebrates and invertebrates,

as well as plants and other single-celled organisms. Some are harmless

or beneficial to their host organisms; others may be significant causes

of diseases, such as babesia, malaria and toxoplasmosis.

Isotricha intestinalis, a ciliate present in the rumen of sheep.

Association between protozoan symbionts and their host organisms can be mutually beneficial. Flagellated protozoans such as Trichonympha and Pyrsonympha inhabit the guts of termites, where they enable their insect host to digest wood by helping to break down complex sugars into smaller, more easily digested molecules. A wide range of protozoans live commensally in the rumens of ruminant animals, such as cattle and sheep. These include flagellates, such as Trichomonas, and ciliated protozoa, such as Isotricha and Entodinium. The ciliate subclass Astomatia is composed entirely of mouthless symbionts adapted for life in the guts of annelid worms.

Feeding

All protozoans are heterotrophic,

deriving nutrients from other organisms, either by ingesting them whole

or consuming their organic remains and waste-products. Some protozoans

take in food by phagocytosis, engulfing organic particles with pseudopodia (as amoebae do), or taking in food through a specialized mouth-like aperture called a cytostome. Others take in food by osmotrophy, absorbing dissolved nutrients through their cell membranes.

Parasitic protozoans use a wide variety of feeding strategies,

and some may change methods of feeding in different phases of their life

cycle. For instance, the malaria parasite Plasmodium feeds by pinocytosis during its immature trophozoite stage of life (ring phase), but develops a dedicated feeding organelle (cytostome) as it matures within a host's red blood cell.

Paramecium bursaria, a ciliate which derives some of its nutrients from algal endosymbionts in the genus Chlorella

Protozoa may also live as mixotrophs, supplementing a heterotrophic diet with some form of autotrophy.

Some protozoa form close associations with symbiotic photosynthetic

algae, which live and grow within the membranes of the larger cell and

provide nutrients to the host. Others practice kleptoplasty, stealing chloroplasts

from prey organisms and maintaining them within their own cell bodies

as they continue to produce nutrients through photosynthesis. The

ciliate Mesodinium rubrum retains functioning plastids

from the cryptophyte algae on which it feeds, using them to nourish

themselves by autotrophy. These, in turn, may be passed along to

dinoflagellates of the genus Dinophysis , which prey on Mesodinium rubrum but keep the enslaved plastids for themselves. Within Dinophysis, these plastids can continue to function for months.

Motility

Organisms traditionally classified as protozoa are abundant in aqueous environments and soil, occupying a range of trophic levels. The group includes flagellates (which move with the help of whip-like structures called flagella), ciliates (which move by using hair-like structures called cilia) and amoebae (which move by the use of foot-like structures called pseudopodia). Some protozoa are sessile, and do not move at all.

Pellicle

Unlike plants, fungi and most types of algae, protozoans do not typically have a rigid cell wall,

but are usually enveloped by elastic structures of membranes that

permit movement of the cell. In some protozoans, such as the ciliates

and euglenozoans,

the cell is supported by a composite membranous envelope called the

"pellicle". The pellicle gives some shape to the cell, especially during

locomotion. Pellicles of protozoan organisms vary from flexible and

elastic to fairly rigid. In ciliates and Apicomplexa, the pellicle is supported by closely packed vesicles called alveoli. In euglenids, it is formed from protein strips arranged spirally along the length of the body. Familiar examples of protists with a pellicle are the euglenoids and the ciliate Paramecium. In some protozoa, the pellicle hosts epibiotic bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae (attachment pili).

Resting cyst of ciliated protozoan Dileptus viridis.

Life cycle

Life cycle of parasitic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii

Some protozoa have two-phase life cycles, alternating between proliferative stages (e.g., trophozoites) and dormant cysts.

As cysts, protozoa can survive harsh conditions, such as exposure to

extreme temperatures or harmful chemicals, or long periods without

access to nutrients, water, or oxygen for periods of time. Being a cyst

enables parasitic species to survive outside of a host, and allows their

transmission from one host to another. When protozoa are in the form of

trophozoites (Greek tropho

= to nourish), they actively feed. The conversion of a trophozoite to

cyst form is known as encystation, while the process of transforming

back into a trophozoite is known as excystation.

All protozoans reproduce (not all) asexually by binary fission or multiple fission. Many protozoan species exchange genetic material by sexual means (typically, through conjugation);

however, sexuality is generally decoupled from the process of

reproduction, and does not immediately result in increased population.

Although meiotic sex is widespread among present day eukaryotes,

it has, until recently, been unclear whether or not eukaryotes were

sexual early in their evolution. Due to recent advances in gene

detection and other techniques, evidence has been found for some form

of meiotic sex in an increasing number of protozoans of ancient lineage

that diverged early in eukaryotic evolution. Thus, such findings suggest that meiotic sex arose early in eukaryotic

evolution. Examples of protozoan meiotic sexuality are described in the

articles Amoebozoa, Giardia lamblia, Leishmania, Plasmodium falciparum biology, Paramecium, Toxoplasma gondii, Trichomonas vaginalis and Trypanosoma brucei.

Classification

Historically,

the Protozoa were classified as "unicellular animals", as distinct from

the Protophyta, single-celled photosynthetic organisms (algae) which

were considered primitive plants. Both groups were commonly given the

rank of phylum, under the kingdom Protista.

In older systems of classification, the phylum Protozoa was commonly

divided into several sub-groups, reflecting the means of locomotion. Classification schemes differed, but throughout much of the 20th century the major groups of Protozoa included:

- Flagellates, or Mastigophora (motile cells equipped with whiplike organelles of locomotion, e.g., Giardia lamblia)

- Amoebae or Sarcodina (cells that move by extending pseudopodia or lamellipodia, e.g., Entamoeba histolytica)

- Sporozoans, or Sporozoa (parasitic, spore-producing cells, whose adult form lacks organs of motility, e.g., Plasmodium knowlesi)

- Apicomplexa (now in Alveolata)

- Microsporidia (now in Fungi)

- Ascetosporea (now in Rhizaria)

- Myxosporidia (now in Cnidaria)

- Ciliates, or Ciliophora (cells equipped with large numbers of short hairlike organs of locomotion, e.g., Balantidium coli

With the emergence of molecular phylogenetics

and tools enabling researchers to directly compare the DNA of different

organisms, it became evident that, of the main sub-groups of Protozoa,

only the ciliates (Ciliophora) formed a natural group, or monophyletic clade (that is, a distinct lineage of organisms sharing common ancestry). The other classes or subphyla of Protozoa were all polyphyletic

groups composed of organisms that, despite similarities of appearance

or way of life, were not necessarily closely related to one another. In

the system of eukaryote

classification currently endorsed by the International Society of

Protistologists, members of the old phylum Protozoa have been

distributed among a variety of supergroups.

Ecology

As components of the micro- and meiofauna, protozoa are an important food source for microinvertebrates. Thus, the ecological role of protozoa in the transfer of bacterial and algal production to successive trophic levels is important. As predators, they prey upon unicellular or filamentous algae, bacteria, and microfungi. Protozoan species include both herbivores and consumers in the decomposer link of the food chain. They also control bacteria populations and biomass to some extent.

Disease

Trophozoites of the amoebic dysentery pathogen Entamoeba histolytica with ingested human red blood cells (dark circles)

A number of protozoan pathogens are human parasites, causing diseases such as malaria (by Plasmodium), amoebiasis, giardiasis, toxoplasmosis, cryptosporidiosis, trichomoniasis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), amoebic dysentery, acanthamoeba keratitis, and primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (naegleriasis).

The protozoan Ophryocystis elektroscirrha is a parasite of butterfly larvae, passed from female to caterpillar. Severely infected individuals are weak, unable to expand their wings, or unable to eclose, and have shortened lifespans, but parasite levels vary in populations. Infection creates a culling

effect, whereby infected migrating animals are less likely to complete

the migration. This results in populations with lower parasite loads at

the end of the migration. This is not the case in laboratory or commercial rearing, where after a few generations, all individuals can be infected.