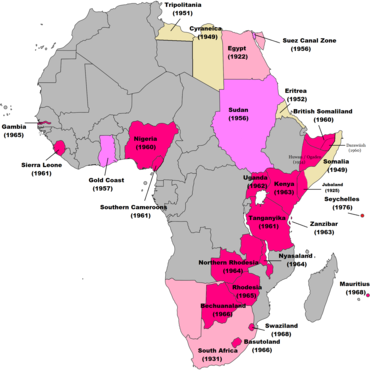

An animated map shows the order of independence of African nations, 1950–2011

The decolonisation of Africa took place in the mid-to-late 1950s to 1975, with sudden and radical regime changes on the continent as colonial governments made the transition to independent states;

this was often quite unorganized and marred with violence and political

turmoil. There was widespread unrest, with organized revolts in both

northern and sub-Saharan colonies including the Algerian War in French Algeria, the Angolan War of Independence in Portuguese Angola, the Congo Crisis in the Belgian Congo, and the Mau Mau Uprising in British Kenya.

Background

The "Scramble for Africa"

between 1870 and 1900 ended with almost all of Africa being controlled

by a small number of European states. Racing to secure as much land as

possible while avoiding conflict amongst themselves, the partition of

Africa was confirmed in the Berlin Agreement of 1885, with little regard to local differences. By 1905, control of almost all African soil was claimed by Western European governments, with the only exceptions being Liberia (which had been settled by African-American former slaves) and Ethiopia (then occupied by Italy in 1936). Britain and France had the largest holdings, but Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, and Portugal also had colonies. As a result of colonialism and imperialism,

a majority of Africa lost sovereignty and control of natural resources

such as gold and rubber. The introduction of imperial policies surfacing

around local economies led to the failing of local economies due to an

exploitation of resources and cheap labor.

Progress towards independence was slow up until the mid-20th century.

By 1977, 54 African countries had seceded from European colonial rulers.

Causes

External causes

During the world wars, African soldiers were conscripted into imperial militaries.

This led to a deeper political awareness and the expectation of greater

respect and self-determination, which was left largely unfulfilled.

During the 1941 Atlantic Conference, the British and the US leaders met

to discuss ideas for the post-war world. One of the provisions added by

President Roosevelt was that all people had the right to

self-determination, inspiring hope in British colonies.

On February 12, 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss the postwar world. The result was the Atlantic Charter. It was not a treaty and was not submitted to the British Parliament or the Senate of the United States for ratification, but it turned out to be a widely acclaimed document. One of the provisions, introduced by Roosevelt, was the autonomy of imperial colonies. After World War II,

the US and the African colonies put pressure on Britain to abide by the

terms of the Atlantic Charter. After the war, some Britons considered

African colonies to be childish and immature; British colonisers

introduced democratic government at local levels in the colonies.

Britain was forced to agree but Churchill rejected universal

applicability of self-determination for subject nations. He also stated

that the Charter was only applicable to German occupied states, not to

the British Empire.

Furthermore, colonies such as Nigeria, Senegal and Ghana pushed

for self-governance as colonial powers were exhausted by war efforts.

Internal causes

For early African nationalists, decolonisation was a moral imperative. In 1945 the Fifth Pan-African Congress demanded the end of colonialism. Delegates included future presidents of Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and national activists.

Colonial economic exploitation led to European extraction of

Ghana’s mining profits to shareholders, instead of internal development,

causing major local socioeconomic grievances. Nevertheless, local African industry and towns expanded when U-boats patrolling the Atlantic Ocean reduced raw material transportation to Europe.

In turn, urban communities, industries and trade unions grew, improving

literacy and education, leading to pro-independence newspaper

establishments.

Indeed, in the 1930s, the colonial powers had cultivated,

sometimes inadvertently, a small elite of leaders educated in Western

universities and familiar with ideas such as self-determination. In some cases where the road to independence was fought, settled arrangements with the colonial powers were also being placed. These leaders came to lead the struggles for independence, and included leading nationalists such as Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Kwame Nkrumah (Gold Coast, now Ghana), Julius Nyerere (Tanganyika, now Tanzania), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal), Nnamdi Azikiwe (Nigeria), and Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d'Ivoire).

Economic legacy

There

is an extensive body of literature that has examined the legacy of

colonialism and colonial institutions on economic outcomes in Africa,

with numerous studies showing an adverse and persistent impact of

colonialism.

The economic legacy of colonialism is difficult to quantify but is likely to have been negative. Modernisation theory emphasises that colonial powers built infrastructure to integrate Africa into the world economy,

however, this was built mainly for extraction purposes. African

economies were structured to benefit the coloniser and any surplus was

likely to be ‘drained’, thereby stifling capital accumulation. Dependency theory

suggests that most African economies continued to occupy a subordinate

position in the world economy after independence with a reliance on

primary commodities such as copper in Zambia and tea in Kenya. Despite this continued reliance and unfair trading terms, a meta-analysis of 18 African countries found that a third of countries experienced increased economic growth post-independence.

Social legacy

Language

Scholars

including Dellal (2013), Miraftab (2012) and Bamgbose (2011) have

argued that Africa’s linguistic diversity has been eroded. Language has

been used by western colonial powers to divide territories and create

new identities which has led to conflicts and tensions between African

nations.

Transition to independence

Following World War II, rapid decolonisation swept across the

continent of Africa as many territories gained their independence from

European colonisation.

In August 1941, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met to discuss their post-war

goals. In that meeting, they agreed to the Atlantic Charter, which in

part stipulated that they would, "respect the right of all peoples to

choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish

to see sovereign rights and self government restored to those who have

been forcibly deprived of them." This agreement became the post-WWII stepping stone toward independence as nationalism grew throughout Africa.

Consumed with post-war debt, European powers were no longer able

to afford the resources needed to maintain control of their African

colonies. This allowed for African nationalists to negotiate

decolonisation very quickly and with minimal casualties. Some

territories, however, saw great death tolls as a result of their fight

for independence.

British Empire

British Empire by 1959

Ghana

On 6 March 1957, Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast) became the first

sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence from European

colonisation. Starting in 1945 Pan-African Congress, Gold Coast’s British- and American-educated independence leader Kwame Nkrumah

made his focus clear. In the conference’s declaration, he wrote, “we

believe in the rights of all peoples to govern themselves. We affirm the

right of all colonial peoples to control their own destiny. All

colonies must be free from foreign imperialist control, whether

political or economic.”

British decolonisation in Africa. By 1970 all but Rhodesia (the future Zimbabwe) and the South African mandate of South West Africa (Namibia) were decolonised.

In 1949, the conflict would ramp up when British troops opened fire

on African protesters. Riots broke out across the territory and while

Nkrumah and other leaders ended up in prison, the event became a

catalyst for the independence movement. After being released from

prison, Nkrumah founded the Convention People’s Party (CPP), which launched a mass-based campaign for independence with the slogan ‘Self Government Now!’” Heightened nationalism within the country grew their power and the political party widely expanded. In February of 1951, the Convention People's Party

gained political power by winning 34 of 38 elected seats, including one

for Nkrumah who was imprisoned at the time. London revised the Gold

Coast Constitution to give Blacks a majority in the legislature in 1951.

In 1956 they requested independence inside the Commonwealth, which was

granted peacefully in 1957 with Nkrumah as prime minister and Queen

Elizabeth as sovereign.

Winds of Change

Prime Minister Harold Macmillan gave the famous "Wind of Change" speech in South Africa in February 1960, where he spoke of "the wind of change blowing through this continent". Macmillan urgently wanted to avoid the same kind of colonial war that France was fighting in Algeria. Under his premiership decolonisation proceeded rapidly.

Britain's remaining colonies in Africa, except for Southern Rhodesia,

were all granted independence by 1968. British withdrawal from the

southern and eastern parts of Africa was not a peaceful process. Kenyan

independence was preceded by the eight-year Mau Mau Uprising. In Rhodesia, the 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence by the white minority resulted in a civil war that lasted until the Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which set the terms for recognised independence in 1980, as the new nation of Zimbabwe.

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire began to fall during the Second World War

when the Vichy France regime controlled the Empire. But one after

another most of the colonies were occupied by foreign powers (Japan in

Indochina, Britain in Syria, Lebanon, and Madagascar, the United States and Britain in Morocco and Algeria, and Germany and Italy in Tunisia). However, control was gradually reestablished by Charles de Gaulle,

who uses colonial base as a launching point to expel Vichy from

Metropolitan France. De Gaulle together with most Frenchmen was

committed to preserving the Empire in the new form. The French Union, included in the Constitution of 1946,

nominally replaced the former colonial empire, but officials in Paris

remained in full control. The colonies were given local assemblies with

only limited local power and budgets. There emerged a group of elites,

known as evolués, who were natives of the overseas territories but lived

in metropolitan France.

De Gaulle assembled a major conference of Free France colonies

in Brazzaville, in Africa, in January–February, 1944. The survival of

France depended on support from these colonies, and De Gaulle made

numerous concessions. They included the end of forced labor, the end of

special legal restrictions that apply to natives but not to whites, the

establishment of elected territorial assemblies, representation in Paris

in a new "French Federation", and the eventual representation of

Sub-Saharan Africans in the French Assembly. However, Independence was

explicitly rejected as a future possibility:

- The ends of the civilizing work accomplished by France in the colonies excludes any idea of autonomy, all possibility of evolution outside the French bloc of the Empire; the eventual Constitution, even in the future of self-government in the colonies is denied.

Conflict

France was immediately confronted with the beginnings of the decolonisation movement. In Algeria demonstrations in May 1945 were repressed with an estimated 6,000 Algerians killed. Unrest in Haiphong, Indochina, in November 1945 was met by another warship bombarding the city. Paul Ramadier's (SFIO) cabinet repressed the Malagasy Uprising

in Madagascar in 1947. French officials estimated the number of

Malagasy killed from a low of 11,000 to a French Army estimate of

89,000.

In France's African colonies, Cameroun, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon's insurrection, started in 1955 and headed by Ruben Um Nyobé, was violently repressed over a two-year period, with perhaps as many as 100 people killed.

Algeria

French involvement in Algeria stretched back a century. Ferhat Abbas and Messali Hadj's movements had marked the period between the two wars, but both sides radicalised after the Second World War. In 1945, the Sétif massacre was carried out by the French army. The Algerian War started in 1954. Atrocities characterized both sides, and the number killed became highly controversial estimates that were made for propaganda purposes. Algeria was a three-way conflict due to the large number of "pieds-noirs" (Europeans who had settled there in the 125 years of French rule). The political crisis in France caused the collapse of the Fourth Republic, as Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958 and finally pulled the French soldiers and settlers out of Algeria by 1962. Lasting more than eight years, the estimated death toll typically falls between 300,000 and 400,000 people. By 1958, the FLN

was able to negotiate peace accord with French President Charles de

Gaulle and nearly 90% of all Europeans had left the territory.

French Community

The special territories of the European Union c. 2011

The French Union was replaced in the new 1958 Constitution of 1958 by the French Community. Only Guinea

refused by referendum to take part in the new colonial organisation.

However, the French Community dissolved itself in the midst of the

Algerian War; almost all of the other African colonies were granted

independence in 1960, following local referendums. Some few colonies

chose instead to remain part of France, under the status of overseas départements (territories). Critics of neocolonialism claimed that the Françafrique

had replaced formal direct rule. They argued that while de Gaulle was

granting independence on one hand, he was creating new ties with the

help of Jacques Foccart, his counsellor for African matters. Foccart supported in particular the Nigerian Civil War during the late 1960s.

Robert Aldrich argues that with Algerian independence in 1962, it

appeared that the Empire practically had come to an end, as the

remaining colonies were quite small and lacked active nationalist

movements. However, there was trouble in French Somaliland (Djibouti), which became independent in 1977. There also were complications and delays in the New Hebrides Vanuatu, which was the last to gain independence in 1980. New Caledonia remains a special case under French suzerainty. The Indian Ocean island of Mayotte voted in referendum in 1974 to retain its link with France and forgo independence.