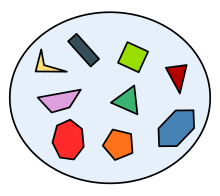

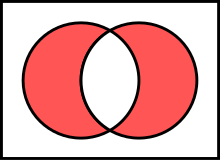

A set of polygons in an Euler diagram

In mathematics, a set is a well-defined collection of distinct objects, considered as an object in its own right.

The arrangement of the objects in the set does not matter. For

example, the numbers 2, 4, and 6 are distinct objects when considered

separately, but when they are considered collectively they form a single

set of size three, written as {2, 4, 6}, which could also be written as

{2, 6, 4}.

The concept of a set is one of the most fundamental in mathematics. Developed at the end of the 19th century, set theory is now a ubiquitous part of mathematics, and can be used as a foundation from which nearly all of mathematics can be derived.

Etymology

The German word Menge, rendered as "set" in English, was coined by Bernard Bolzano in his work The Paradoxes of the Infinite.

Definition

Passage with a translation of the original set definition of Georg Cantor. The German word Menge for set is translated with aggregate here.

A set is a well-defined collection of distinct objects. The objects that make up a set (also known as the set's elements or members) can be anything: numbers, people, letters of the alphabet, other sets, and so on. Georg Cantor, one of the founders of set theory, gave the following definition of a set at the beginning of his Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre:

A set is a gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception [Anschauung] or of our thought—which are called elements of the set.

Sets are conventionally denoted with capital letters. Sets A and B are equal if and only if they have precisely the same elements.

For technical reasons, Cantor's definition turned out to be

inadequate; today, in contexts where more rigor is required, one can use

axiomatic set theory, in which the notion of a "set" is taken as a primitive notion and the properties of sets are defined by a collection of axioms.

The most basic properties are that a set can have elements, and that

two sets are equal (one and the same) if and only if every element of

each set is an element of the other; this property is called the extensionality of sets.

Set notation

There are two common ways of describing, or specifying the members of, a set: roster notation and set builder notation. These are examples of extensional and intensional definitions of sets, respectively.

Roster notation

The Roster notation (or enumeration notation) method of defining a set consist of listing each member of the set. More specifically, in roster notation (an example of extensional definition), the set is denoted by enclosing the list of members in curly brackets:

- A = {4, 2, 1, 3}

- B = {blue, white, red}.

For sets with many elements, the enumeration of members can be abbreviated. For instance, the set of the first thousand positive integers may be specified in roster notation as

- {1, 2, 3, ..., 1000},

where the ellipsis ("...") indicates that the list continues in according to the demonstrated pattern.

In roster notation, listing a member repeatedly does not change

the set, for example, the set {11, 6, 6} is identical to the set {11,

6}. Moreover, the order in which the elements of a set are listed is irrelevant (unlike for a sequence or tuple), so {6, 11} is yet again the same set.

Set-builder notation

In set-builder notation, the set is specified as a subset of a larger set, where the subset is

determined by a statement or condition involving the elements. For example, a set F can be specified as follows:

In this notation, the vertical bar ("|") means "such that", and the description can be interpreted as "F is the set of all numbers n, such that n is an integer in the range from 0 to 19 inclusive". Sometimes the colon (":") is used instead of the vertical bar.

Set-builder notation is an example of intensional definition.

Other ways of defining sets

Another method is by using a rule or semantic description:

- A is the set whose members are the first four positive integers.

- B is the set of colors of the French flag.

This is another example of intensional definition.

Membership

If B is a set and x is one of the objects of B, this is denoted as x ∈ B, and is read as "x is an element of B", as "x belongs to B", or "x is in B". If y is not a member of B then this is written as y ∉ B, read as "y is not an element of B", or "y is not in B".

For example, with respect to the sets A = {1, 2, 3, 4}, B = {blue, white, red}, and F = {n | n is an integer, and 0 ≤ n ≤ 19},

- 4 ∈ A and 12 ∈ F; and

- 20 ∉ F and green ∉ B.

Subsets

If every element of set A is also in B, then A is said to be a subset of B, written A ⊆ B (pronounced A is contained in B). Equivalently, one can write B ⊇ A, read as B is a superset of A, B includes A, or B contains A. The relationship between sets established by ⊆ is called inclusion or containment. Two sets are equal if they contain each other: A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A is equivalent to A = B.

If A is a subset of B, but not equal to B, then A is called a proper subset of B, written A ⊊ B, or simply A ⊂ B (A is a proper subset of B), or B ⊋ A (B is a proper superset of A, B ⊃ A).

The expressions A ⊂ B and B ⊃ A are used differently by different authors; some authors use them to mean the same as A ⊆ B (respectively B ⊇ A), whereas others use them to mean the same as A ⊊ B (respectively B ⊋ A).

A is a subset of B

Examples:

- The set of all humans is a proper subset of the set of all mammals.

- {1, 3} ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4}.

- {1, 2, 3, 4} ⊆ {1, 2, 3, 4}.

There is a unique set with no members, called the empty set (or the null set), which is denoted by the symbol ∅ (other notations are used; see empty set).

The empty set is a subset of every set, and every set is a subset of itself:

- ∅ ⊆ A.

- A ⊆ A.

Partitions

A partition of a set S is a set of nonempty subsets of S such that every element x in S is in exactly one of these subsets. That is, the subsets are pairwise disjoint (meaning any two sets of the partition contain no element in common), and the union of all the subsets of the partition is S.

Power sets

The power set of a set S is the set of all subsets of S. The power set contains S itself and the empty set because these are both subsets of S.

For example, the power set of the set {1, 2, 3} is {{1, 2, 3}, {1, 2},

{1, 3}, {2, 3}, {1}, {2}, {3}, ∅}. The power set of a set S is usually written as P(S).

The power set of a finite set with n elements has 2n elements. For example, the set {1, 2, 3} contains three elements, and the power set shown above contains 23 = 8 elements.

The power set of an infinite (either countable or uncountable)

set is always uncountable. Moreover, the power set of a set is always

strictly "bigger" than the original set in the sense that there is no

way to pair every element of S with exactly one element of P(S). (There is never an onto map or surjection from S onto P(S).)

Cardinality

The cardinality of a set S, denoted |S|, is the number of members of S. For example, if B = {blue, white, red}, then |B| = 3. Repeated members in roster notation are not counted, so |{blue, white, red, blue, white}| = 3, too.

The cardinality of the empty set is zero.

Some sets have infinite cardinality. The set N of natural numbers, for instance, is infinite. Some infinite cardinalities are greater than others. For instance, the set of real numbers has greater cardinality than the set of natural numbers. However, it can be shown that the cardinality of (which is to say, the number of points on) a straight line is the same as the cardinality of any segment of that line, of the entire plane, and indeed of any finite-dimensional Euclidean space.

Special sets

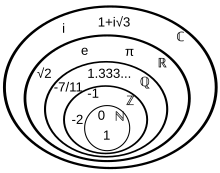

The natural numbers ℕ are contained in the integers ℤ, which are contained in the rational numbers ℚ, which are contained in the real numbers ℝ, which are contained in the complex numbers ℂ

There are some sets or kinds of sets that hold great mathematical

importance and are referred to with such regularity that they have

acquired special names and notational conventions to identify them. One

of these is the empty set, denoted { } or ∅. A set with exactly one element, x, is a unit set, or singleton, {x}.

Many of these sets are represented using bold (e.g. P) or blackboard bold (e.g. ℙ) typeface.

Special sets of numbers include

- P or ℙ, denoting the set of all primes: P = {2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, ...}.

- N or , denoting the set of all natural numbers: N = {0, 1, 2, 3, ...} (sometimes defined excluding 0).

- Z or , denoting the set of all integers (whether positive, negative or zero): Z = {..., −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, ...}.

- Q or ℚ, denoting the set of all rational numbers (that is, the set of all proper and improper fractions): Q = {a/b | a, b ∈ Z, b ≠ 0}. For example, 1/4 ∈ Q and 11/6 ∈ Q. All integers are in this set since every integer a can be expressed as the fraction a/1 (Z ⊊ Q).

- R or , denoting the set of all real numbers. This set includes all rational numbers, together with all irrational numbers (that is, algebraic numbers that cannot be rewritten as fractions such as √2, as well as transcendental numbers such as π, e).

- C or ℂ, denoting the set of all complex numbers: C = {a + bi | a, b ∈ R}. For example, 1 + 2i ∈ C.

- H or ℍ, denoting the set of all quaternions: H = {a + bi + cj + dk | a, b, c, d ∈ R}. For example, 1 + i + 2j − k ∈ H.

Each of the above sets of numbers has an infinite number of elements,

and each can be considered to be a proper subset of the sets listed

below it. The primes are used less frequently than the others outside of

number theory and related fields.

Positive and negative sets are sometimes denoted by superscript plus and minus signs, respectively. For example, ℚ+ represents the set of positive rational numbers.

Basic operations

There are several fundamental operations for constructing new sets from given sets.

Unions

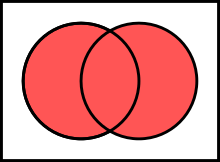

The union of A and B, denoted A ∪ B

Two sets can be "added" together. The union of A and B, denoted by A ∪ B, is the set of all things that are members of either A or B.

Examples:

- {1, 2} ∪ {1, 2} = {1, 2}.

- {1, 2} ∪ {2, 3} = {1, 2, 3}.

- {1, 2, 3} ∪ {3, 4, 5} = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

Some basic properties of unions:

- A ∪ B = B ∪ A.

- A ∪ (B ∪ C) = (A ∪ B) ∪ C.

- A ⊆ (A ∪ B).

- A ∪ A = A.

- A ∪ ∅ = A.

- A ⊆ B if and only if A ∪ B = B.

Intersections

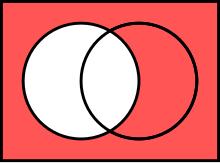

A new set can also be constructed by determining which members two sets have "in common". The intersection of A and B, denoted by A ∩ B, is the set of all things that are members of both A and B. If A ∩ B = ∅, then A and B are said to be disjoint.

The intersection of A and B, denoted A ∩ B.

Examples:

- {1, 2} ∩ {1, 2} = {1, 2}.

- {1, 2} ∩ {2, 3} = {2}.

- {1, 2} ∩ {3, 4} = ∅.

Some basic properties of intersections:

- A ∩ B = B ∩ A.

- A ∩ (B ∩ C) = (A ∩ B) ∩ C.

- A ∩ B ⊆ A.

- A ∩ A = A.

- A ∩ ∅ = ∅.

- A ⊆ B if and only if A ∩ B = A.

Complements

The relative complement

of B in A

of B in A

The complement of A in U

The symmetric difference of A and B

Two sets can also be "subtracted". The relative complement of B in A (also called the set-theoretic difference of A and B), denoted by A \ B (or A − B), is the set of all elements that are members of A but not members of B. It is valid to "subtract" members of a set that are not in the set, such as removing the element green from the set {1, 2, 3}; doing so has no effect.

In certain settings all sets under discussion are considered to be subsets of a given universal set U. In such cases, U \ A is called the absolute complement or simply complement of A, and is denoted by A′.

- A′ = U \ A

Examples:

- {1, 2} \ {1, 2} = ∅.

- {1, 2, 3, 4} \ {1, 3} = {2, 4}.

- If U is the set of integers, E is the set of even integers, and O is the set of odd integers, then U \ E = E′ = O.

Some basic properties of complements:

- A \ B ≠ B \ A for A ≠ B.

- A ∪ A′ = U.

- A ∩ A′ = ∅.

- (A′)′ = A.

- ∅ \ A = ∅.

- A \ ∅ = A.

- A \ A = ∅.

- A \ U = ∅.

- A \ A′ = A and A′ \ A = A′.

- U′ = ∅ and ∅′ = U.

- A \ B = A ∩ B′.

- if A ⊆ B then A \ B = ∅.

An extension of the complement is the symmetric difference, defined for sets A, B as

For example, the symmetric difference of {7, 8, 9, 10} and {9, 10,

11, 12} is the set {7, 8, 11, 12}. The power set of any set becomes a Boolean ring

with symmetric difference as the addition of the ring (with the empty

set as neutral element) and intersection as the multiplication of the

ring.

Cartesian product

A new set can be constructed by associating every element of one set with every element of another set. The Cartesian product of two sets A and B, denoted by A × B is the set of all ordered pairs (a, b) such that a is a member of A and b is a member of B.

Examples:

- {1, 2} × {red, white, green} = {(1, red), (1, white), (1, green), (2, red), (2, white), (2, green)}.

- {1, 2} × {1, 2} = {(1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 1), (2, 2)}.

- {a, b, c} × {d, e, f} = {(a, d), (a, e), (a, f), (b, d), (b, e), (b, f), (c, d), (c, e), (c, f)}.

Some basic properties of Cartesian products:

- A × ∅ = ∅.

- A × (B ∪ C) = (A × B) ∪ (A × C).

- (A ∪ B) × C = (A × C) ∪ (B × C).

Let A and B be finite sets; then the cardinality of the Cartesian product is the product of the cardinalities:

- | A × B | = | B × A | = | A | × | B |.

Applications

Set theory is seen as the foundation from which virtually all of mathematics can be derived. For example, structures in abstract algebra, such as groups, fields and rings, are sets closed under one or more operations.

One of the main applications of naive set theory is constructing relations. A relation from a domain A to a codomain B is a subset of the Cartesian product A × B. For example, considering the set S = { rock, paper, scissors } of shapes in the game of the same name, the relation "beats" from S to S is the set B = { (scissors,paper), (paper,rock), (rock,scissors) }; thus x beats y in the game if the pair (x,y) is a member of B. Another example is the set F of all pairs (x, x2), where x is real. This relation is a subset of R' × R, because the set of all squares is subset of the set of all real numbers. Since for every x in R, one, and only one, pair (x,...) is found in F, it is called a function. In functional notation, this relation can be written as F(x) = x2.

Axiomatic set theory

Although initially naive set theory, which defines a set merely as any well-defined collection, was well accepted, it soon ran into several obstacles. It was found that this definition spawned several paradoxes, most notably:

- Russell's paradox – It shows that the "set of all sets that do not contain themselves," i.e. the "set" {x|x is a set and x ∉ x} does not exist.

- Cantor's paradox – It shows that "the set of all sets" cannot exist.

The reason is that the phrase well-defined is not very

well-defined. It was important to free set theory of these paradoxes

because nearly all of mathematics was being redefined in terms of set

theory. In an attempt to avoid these paradoxes, set theory was

axiomatized based on first-order logic, and thus axiomatic set theory was born.

For most purposes, however, naive set theory is still useful.

Principle of inclusion and exclusion

The

inclusion-exclusion principle can be used to calculate the size of the

union of sets: the size of the union is the size of the two sets, minus

the size of their intersection.

The inclusion–exclusion principle is a counting technique that can be

used to count the number of elements in a union of two sets, if the

size of each set and the size of their intersection are known. It can be

expressed symbolically as

A more general form of the principle can be used to find the cardinality of any finite union of sets:

De Morgan's laws

Augustus De Morgan stated two laws about sets.

If A and B are any two sets then,

- (A ∪ B)′ = A′ ∩ B′

The complement of A union B equals the complement of A intersected with the complement of B.

- (A ∩ B)′ = A′ ∪ B′

The complement of A intersected with B is equal to the complement of A union to the complement of B.