A subculture is a group of people within a culture

that differentiates itself from the parent culture to which it belongs,

often maintaining some of its founding principles. Subcultures develop

their own norms and values regarding cultural, political and sexual

matters. Subcultures are part of society while keeping their specific

characteristics intact. Examples of subcultures include hippies, goths, bikers and skinheads. The concept of subcultures was developed in sociology and cultural studies. Subcultures differ from countercultures.

Definitions

While exact definitions vary, the Oxford English Dictionary defines a subculture as "a cultural group within a larger culture, often having beliefs or interests at variance with those of the larger culture."

As early as 1950, David Riesman distinguished between a majority, "which passively accepted commercially

provided styles and meanings, and a 'subculture' which actively sought a

minority style ... and interpreted it in accordance with subversive values". In his 1979 book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Dick Hebdige argued that a subculture is a subversion

to normalcy. He wrote that subcultures can be perceived as negative due

to their nature of criticism to the dominant societal standard.Hebdige

argued that subculture brings together like-minded individuals who feel

neglected by societal standards and allow them to develop a sense of

identity.

In 1995, Sarah Thornton, drawing on Pierre Bourdieu,

described "subcultural capital" as the cultural knowledge and

commodities acquired by members of a subculture, raising their status

and helping differentiate themselves from members of other groups. In 2007, Ken Gelder proposed to distinguish subcultures from countercultures based on the level of immersion in society. Gelder further proposed six key ways in which subcultures can be identified through their:

- often negative relations to work (as 'idle', 'parasitic', at play or at leisure, etc.);

- negative or ambivalent relation to class (since subcultures are not 'class-conscious' and don't conform to traditional class definitions);

- association with territory (the 'street', the 'hood', the club, etc.), rather than property;

- movement out of the home and into non-domestic forms of belonging (i.e. social groups other than the family);

- stylistic ties to excess and exaggeration (with some exceptions);

- refusal of the banalities of ordinary life and massification.

Sociologists Gary Alan Fine and Sherryl Kleinman

argued that their 1979 research showed that a subculture is a group

that serves to motivate a potential member to adopt the artifacts,

behaviors, norms, and values characteristic of the group.

History of studies

The evolution of subcultural studies has three main steps:

Subcultures and deviance

The

earliest subcultures studies came from the so-called Chicago School,

who interpreted them as forms of deviance and delinquency. Starting with

what they called Social Disorganization Theory, they claimed that

subcultures emerged on one hand because of some population sectors’ lack

of socialisation with the mainstream culture and, on the other, because

of their adoption of alternative axiological and normative models. As Robert E. Park, Ernest Burgess and Louis Wirth

suggested, by means of selection and segregation processes, there thus

appear in society natural areas or moral regions where deviant models

concentrate and are re-inforced; they do not accept objectives or means

of action offered by the mainstream culture, proposing different ones in

their place – thereby becoming, depending on circumstances, innovators,

rebels or retreatists (Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin).

Subcultures, however, are not only the result of alternative action

strategies but also of labelling processes on the basis of which, as Howard S. Becker

explains, society defines them as outsiders. As Cohen clarifies, every

subculture’s style, consisting of image, demeanour and language becomes

its recognition trait. And an individual’s progressive adoption of a

subcultural model will furnish him/her with growing status within this

context but it will often, in tandem, deprive him/her of status in the

broader social context outside where a different model prevails.

Cohen used the term 'Corner Boys' which were unable to compete with

their better secured and prepared peers. These lower-class boys did not

have equal access to resources, resulting in the status of frustration

and search for a solution.

Subcultures and resistance

In the work of John Clarke, Stuart Hall, Tony Jefferson and Brian Roberts of the Birmingham CCCS (Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies),

subcultures are interpreted as forms of resistance. Society is seen as

being divided into two fundamental classes, the working class and the

middle class, each with its own class culture, and middle-class culture

being dominant. Particularly in the working class, subcultures grow out

of the presence of specific interests and affiliations around which

cultural models spring up, in conflict with both their parent culture

and mainstream culture. Facing a weakening of class identity,

subcultures are then new forms of collective identification expressing

what Cohen called symbolic resistance against the mainstream culture and

developing imaginary solutions for structural problems. As Paul Willis and Dick Hebdige

underline, identity and resistance are expressed through the

development of a distinctive style which, by a re-signification and

‘bricolage’ operation, use cultural industry goods to communicate and

express one’s own conflict. Yet the cultural industry is often capable

of re-absorbing the components of such a style and once again

transforming them into goods. At the same time the mass media, while

they participate in building subcultures by broadcasting their images,

also weaken them by depriving them of their subversive content or by

spreading a stigmatized image of them.

Subcultures and distinction

The

most recent interpretations see subcultures as forms of distinction. In

an attempt to overcome the idea of subcultures as forms of deviance or

resistance, they describe subcultures as collectivities which, on a

cultural level, are sufficiently homogeneous internally and

heterogeneous with respect to the outside world to be capable of

developing, as Paul Hodkinson points out, consistent distinctiveness,

identity, commitment and autonomy. Defined by Sarah Thornton

as taste cultures, subcultures are endowed with elastic, porous

borders, and are inserted into relationships of interaction and

mingling, rather than independence and conflict, with the cultural

industry and mass media, as Steve Redhead

and David Muggleton emphasize. The very idea of a unique, internally

homogeneous, dominant culture is explicitly criticized. Thus forms of

individual involvement in subcultures are fluid and gradual,

differentiated according to each actor’s investment, outside clear

dichotomies. The ideas of different levels of subcultural capital (Sarah Thornton) possessed by each individual, of the supermarket of style (Ted Polhemus)

and of style surfing (Martina Böse) replace that of the subculture’s

insiders and outsiders – with the perspective of subcultures supplying

resources for the construction of new identities going beyond strong,

lasting identifications.

Identifying

Members of the seminal punk rock band Ramones wearing early punk fashion items such as Converse sneakers, black leather jackets and blue jeans.

The study of subcultures often consists of the study of symbolism attached to clothing, music

and other visible affectations by members of subcultures, and also of

the ways in which these same symbols are interpreted by members of the

dominant culture. Dick Hebdige writes that members of a subculture often

signal their membership through a distinctive and symbolic use of

style, which includes fashions, mannerisms and argot.

Subcultures can exist at all levels of organizations, highlighting

the fact that there are multiple cultures or value combinations usually

evident in any one organization that can complement but also compete

with the overall organisational culture. In some instances, subcultures have been legislated against, and their activities regulated or curtailed. British youth subcultures had been described as a moral problem that ought to be handled by the guardians of the dominant culture within the post-war consensus.

Relationships with mainstream culture

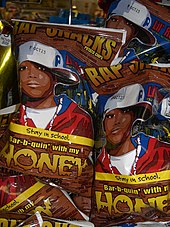

Potato chip packages featuring hip hop subcultural designs in a case of mainstream commercial cultural merging

It may be difficult to identify certain subcultures because their

style (particularly clothing and music) may be adopted by mass culture

for commercial purposes. Businesses often seek to capitalize on the

subversive allure of subcultures in search of Cool, which remains valuable in the selling of any product. This process of cultural appropriation

may often result in the death or evolution of the subculture, as its

members adopt new styles that appear alien to mainstream society.

Music-based subcultures are particularly vulnerable to this

process; what may be considered subcultures at one stage in their

histories – such as jazz, goth, punk, hip hop and rave cultures – may represent mainstream taste within a short period. Some subcultures reject or modify the importance of style, stressing membership through the adoption of an ideology which may be much more resistant to commercial exploitation. The punk subculture's

distinctive (and initially shocking) style of clothing was adopted by

mass-market fashion companies once the subculture became a media

interest. Dick Hebdige argues that the punk subculture shares the same "radical aesthetic practices" as Dada and surrealism:

Like Duchamp's 'ready mades' - manufactured objects which qualified as art because he chose to call them such, the most unremarkable and inappropriate items - a pin, a plastic clothes peg, a television component, a razor blade, a tampon - could be brought within the province of punk (un)fashion ... Objects borrowed from the most sordid of contexts found a place in punks' ensembles; lavatory chains were draped in graceful arcs across chests in plastic bin liners. Safety pins were taken out of their domestic 'utility' context and worn as gruesome ornaments through the cheek, ear or lip ... fragments of school uniform (white bri-nylon shirts, school ties) were symbolically defiled (the shirts covered in graffiti, or fake blood; the ties left undone) and juxtaposed against leather drains or shocking pink mohair tops.

Urban tribes

In 1985, French sociologist Michel Maffesoli coined the term urban tribe. It gained widespread use after the publication of his Le temps des tribus: le déclin de l'individualisme dans les sociétés postmodernes (1988). Eight years later, this book was published in the United Kingdom as The Time of the Tribes: The Decline of Individualism in Mass Society.

According to Maffesoli, urban tribes are microgroups of people

who share common interests in urban areas. The members of these

relatively small groups tend to have similar worldviews, dress styles

and behavioral patterns. Their social interactions are largely informal and emotionally laden, different from late capitalism's corporate-bourgeoisie cultures, based on dispassionate logic. Maffesoli claims that punks are a typical example of an "urban tribe".

Five years after the first English translation of Le temps des tribus, writer Ethan Watters claims to have coined the same neologism in a New York Times Magazine article. This was later expanded upon the idea in his book Urban Tribes: A Generation Redefines Friendship, Family, and Commitment. According to Watters, urban tribes are groups of never-marrieds between the ages of 25 and 45 who gather in common-interest groups and enjoy an urban lifestyle, which offers an alternative to traditional family structures.

Sexual

'Bears' celebrating the 2007 International Bear Rendezvous, an annual gathering of fans of the sexual subculture in San Francisco, CA

The sexual revolution

of the 1960s led to a countercultural rejection of the established

sexual and gender norms, particularly in the urban areas of Europe,

North and South America, Australia, and white South Africa. A more

permissive social environment in these areas led to a proliferation of sexual subcultures—cultural expressions of non-normative sexuality.

As with other subcultures, sexual subcultures adopted certain styles of

fashion and gestures to distinguish them from the mainstream.

Homosexuals expressed themselves through the gay culture,

considered the largest sexual subculture of the 20th century. With the

ever-increasing acceptance of homosexuality in the early 21st century,

including its expressions in fashion, music, and design, the gay culture

can no longer be considered a subculture in many parts of the world,

although some aspects of gay culture like leathermen, bears, and feeders are considered subcultures within the gay movement itself. The butch and femme identities or roles among some lesbians also engender their own subculture with stereotypical attire, for instance drag kings. A late 1980s development, the queer

movement can be considered a subculture broadly encompassing those that

reject normativity in sexual behavior, and who celebrate visibility and

activism. The wider movement coincided with growing academic interests

in queer studies and queer theory. Aspects of sexual subcultures can vary along other cultural lines. For instance, in the United States, down-low refers to African-American men who do not identify themselves with the gay or queer cultures, but who practice gay cruising, and adopt a specific hip-hop attire during this activity.

Social media

In

a 2011 study, Brady Robards and Andy Bennett said that online identity

expression has been interpreted as exhibiting subcultural qualities.

However, they argue it is more in line with neotribalism than with what is often classified as subculture. Social networking websites

are quickly becoming the most used form of communication and means to

distribute information and news. They offer a way for people with

similar backgrounds, lifestyles, professions or hobbies to connect.

According to a co-founder and executive creative strategist for RE-UP,

as technology becomes a "life force," subcultures become the main bone

of contention for brands as networks rise through cultural mash-ups and

phenomenons.

Where social media is concerned, there seems to be a growing interest

among media producers to use subcultures for branding. This is seen most

actively on social network sites with user-generated content, such as YouTube.

Social media expert Scott Huntington cites one of the ways in

which subcultures have been and can be successfully targeted to generate

revenue: "It’s common to assume that subcultures aren’t a major market

for most companies. Online apps for shopping, however, have made

significant strides. Take Etsy, for example. It only allow vendors to

sell handmade or vintage items, both of which can be considered a rather

"hipster" subculture. However, retailers on the site made almost $900

million in sales."

Discrimination

Discrimination is sometimes directed towards a person based on their culture or subculture. In 2013, the Greater Manchester Police in the United Kingdom began to classify attacks on subcultures such as goths, emos, punks and metalheads

as hate crimes, in the same way they record abuse against people

because of their religion, race, disability, sexual orientation or

transgender identity. The decision followed the murder of Sophie Lancaster and beating of her boyfriend in 2007, who were attacked because they were goths.

In 2012, emo killings in Iraq

occurred, which consisted of between at least 6 and up to 70 teenage

boys who were kidnapped, tortured and murdered in Baghdad and Iraq, due

to being targeted because they dressed in a Westernized emo style.