Historical negationism, also called denialism, is falsification or distortion of the historical record. It should not be conflated with historical revisionism, a broader term that extends to newly evidenced, fairly reasoned academic reinterpretations of history. In attempting to revise the past, illegitimate historical revisionism may use techniques inadmissible in proper historical discourse, such as presenting known forged documents as genuine, inventing ingenious but implausible reasons for distrusting genuine documents, attributing conclusions to books and sources that report the opposite, manipulating statistical series to support the given point of view, and deliberately mistranslating texts.

Some countries, such as Germany, have criminalized the negationist revision of certain historical events, while others take a more cautious position for various reasons, such as protection of free speech; others mandate negationist views, such as California and Japan, where schoolchildren are explicitly prevented from learning about the California genocide and Japanese war crimes, respectively. Notable examples of negationism include Holocaust denial, Armenian genocide denial, the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, the myth of the clean Wehrmacht, Japanese history textbook controversies, and historiography in the Soviet Union during the Stalin era. Some notable historical negationists include Arthur Butz, David Irving, and Shinzo Abe. In literature, the consequences of historical negationism have been imaginatively depicted in some works of fiction, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, by George Orwell. In modern times, negationism may spread via new media, such as the Internet.

Origin of the term

The term negationism (négationnisme) was first coined by the French historian Henry Rousso in his 1987 book The Vichy Syndrome which looked at the French popular memory of Vichy France and the French Resistance. Rousso posited that it was necessary to distinguish between legitimate historical revisionism in Holocaust studies and politically motivated denial of the Holocaust, which he termed negationism.

Purposes

Usually, the purpose of historical negation is to achieve a national, political aim, by transferring war-guilt, demonizing an enemy, providing an illusion of victory, or preserving a friendship. Sometimes the purpose of a revised history is to sell more books or to attract attention with a newspaper headline. The historian James M. McPherson said that negationists would want revisionist history understood as, "a consciously-falsified or distorted interpretation of the past to serve partisan or ideological purposes in the present".

Ideological influence

The principal functions of negationist history are the abilities to control ideological influence and to control political influence. In "History Men Battle over Britain's Future", Michael d'Ancona said that historical negationists "seem to have been given a collective task in [a] nation's cultural development, the full significance of which is emerging only now: To redefine [national] status in a changing world". History is a social resource that contributes to shaping national identity, culture, and the public memory. Through the study of history, people are imbued with a particular cultural identity; therefore, by negatively revising history, the negationist can craft a specific, ideological identity. Because historians are credited as people who single-mindedly pursue truth, by way of fact, negationist historians capitalize on the historian's professional credibility, and present their pseudohistory as true scholarship. By adding a measure of credibility to the work of revised history, the ideas of the negationist historian are more readily accepted in the public mind. As such, professional historians recognize the revisionist practice of historical negationism as the work of "truth-seekers" finding different truths in the historical record to fit their political, social, and ideological contexts.

Political influence

History provides insight into past political policies and consequences, and thus assists people in extrapolating political implications for contemporary society. Historical negationism is applied to cultivate a specific political myth, sometimes with official consent from the government, whereby self-taught, amateur, and dissident academic historians either manipulate or misrepresent historical accounts to achieve political ends. Since the late 1930s in the Soviet Union, the ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and historiography in the Soviet Union treated reality and the party line as the same intellectual entity, especially in regards to the Russian Civil War and peasants rebellions; Soviet historical negationism advanced a specific, political, and ideological agenda about Russia and its place in world history.

Techniques

Historical negationism applies the techniques of research, quotation, and presentation for deception of the reader and denial of the historical record. In support of the "revised history" perspective, the negationist historian uses false documents as genuine sources, presents specious reasons to distrust genuine documents, exploits published opinions by quoting out of historical context, manipulates statistics, and mistranslates texts in other languages. The revision techniques of historical negationism operate in the intellectual space of public debate for the advancement of a given interpretation of history and the cultural perspective of the "revised history". As a document, the revised history is used to negate the validity of the factual, documentary record, and so reframe explanations and perceptions of the discussed historical event, to deceive the reader, the listener, and the viewer; therefore, historical negationism functions as a technique of propaganda. Rather than submit their works for peer review, negationist historians rewrite history and use logical fallacies to construct arguments that will obtain the desired results, a "revised history" that supports an agenda – political, ideological, religious, etc.

In the practice of historiography, the British historian Richard J. Evans describes the technical differences, between professional historians and negationist historians, commenting: "Reputable and professional historians do not suppress parts of quotations from documents that go against their own case, but take them into account, and, if necessary, amend their own case, accordingly. They do not present, as genuine, documents which they know to be forged, just because these forgeries happen to back up what they are saying. They do not invent ingenious, but implausible, and utterly unsupported reasons for distrusting genuine documents, because these documents run counter to their arguments; again, they amend their arguments, if this is the case, or, indeed, abandon them altogether. They do not consciously attribute their own conclusions to books and other sources, which, in fact, on closer inspection, actually say the opposite. They do not eagerly seek out the highest possible figures in a series of statistics, independently of their reliability, or otherwise, simply because they want, for whatever reason, to maximize the figure in question, but rather, they assess all the available figures, as impartially as possible, to arrive at a number that will withstand the critical scrutiny of others. They do not knowingly mistranslate sources in foreign languages to make them more serviceable to themselves. They do not willfully invent words, phrases, quotations, incidents and events, for which there is no historical evidence, to make their arguments more plausible."

Deception

Deception includes falsifying information, obscuring the truth, and lying to manipulate public opinion about the historical event discussed in the revised history. The negationist historian applies the techniques of deception to achieve either a political or an ideological goal, or both. The field of history distinguishes among history books based upon credible, verifiable sources, which were peer-reviewed before publication; and deceptive history books, based upon unreliable sources, which were not submitted for peer review. The distinction among types of history books rests upon the research techniques used in writing a history. Verifiability, accuracy, and openness to criticism are central tenets of historical scholarship. When these techniques are sidestepped, the presented historical information might be deliberately deceptive, a "revised history".

Denial

Denial is defensively protecting information from being shared with other historians, and claiming that facts are untrue, especially denial of the war crimes and crimes against humanity perpetrated in the course of the World War II (1939–45) and the Holocaust (1933–45). The negationist historian protects the historical-revisionism project by blame shifting, censorship, distraction, and media manipulation; occasionally, denial by protection includes risk management for the physical security of revisionist sources.

Relativization and trivialization

Comparing certain historical atrocities to other crimes is the practice of relativization, interpretation by moral judgements, to alter public perception of the first historical atrocity. Although such comparisons often occur in negationist history, their pronouncement is not usually part of revisionist intentions upon the historical facts, but an opinion of moral judgement.

- The Holocaust and Nazism: The historian Deborah Lipstadt says that the concept of "comparable Allied wrongs", such as the expulsion of Germans after World War II from Nazi-colonized lands and the formal Allied war crimes, is at the centre of, and is a continually repeated theme of, contemporary Holocaust denial, and that such relativization presents "immoral equivalencies".

- Proponents of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy often use historical examples of non-chattel slavery to claim that enslaved white and black slaves faced the same conditions. While other forms are abhorrent, only the former involves legally-mandated generational slavery.

Book burning

Repositories of literature have been targeted throughout history (e.g., the Library of Alexandria, Grand Library of Baghdad), burning of the liturgical and historical books of the St. Thomas Christians by the archbishop of Goa Aleixo de Menezes, including recently, such as the 1981 Burning of Jaffna library and the destruction of Iraqi libraries by ISIS during the fall of Mosul in 2014.

Chinese book burning

The Burning of books and burying of scholars (traditional Chinese: 焚書坑儒; simplified Chinese: 焚书坑儒; pinyin: fénshū kēngrú; lit. 'burning of books and burying (alive) of (Confucian) scholars'), or "Fires of Qin", refers to the burning of writings and slaughter of scholars during the Qin Dynasty of Ancient China, between the period of 213 and 210 BC. "Books" at this point refers to writings on bamboo strips, which were then bound together. This contributed to the loss to history of many philosophical theories of proper government (known as "the Hundred Schools of Thought"). The official philosophy of government ("legalism") survived.

United States history

Confederate revisionism

The historical negationism of American Civil War revisionists and Neo-Confederates claims that the Confederate States (1861–65) were the defenders rather than the instigators of the American Civil War, and that the Confederacy's motivation for secession from the United States was the maintenance of the Southern states' rights and limited government, rather than the preservation and expansion of chattel slavery.

Regarding Neo-Confederate revisionism of the U.S. Civil War, the historian Brooks D. Simpson says: "This is an active attempt to reshape historical memory, an effort by white Southerners to find historical justifications for present-day actions. The neo–Confederate movement's ideologues have grasped that if they control how people remember the past, they'll control how people approach the present and the future. Ultimately, this is a very conscious war for memory and heritage. It's a quest for legitimacy, the eternal quest for justification."

In the early 20th century, Mildred Rutherford, the historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), led the attack against American history textbooks that did not present the "Lost Cause of the Confederacy" version of the history of the U.S. Civil War. To that pedagogical end, Rutherford assembled a "massive collection" of documents that included "essay contests on the glory of the Ku Klux Klan and personal tributes to faithful slaves". About the historical negationism of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the historian David Blight says: "All UDC members and leaders were not as virulently racist as Rutherford, but all, in the name of a reconciled nation, participated in an enterprise that deeply influenced the white supremacist vision of Civil War memory."

California genocide

Between 1846 and 1870, during and after the conquest of California by the United States, the region's Native American population plummeted from around 150,000 to around 30,000 due primarily to forced removals, slavery, and massacres perpetrated by both government forces and by white settlers in what most historians consider to be an act of genocide. Despite extremely well documented evidence of widespread mass murder and other atrocities perpetrated by American settlers during this time period, the public school curriculum and history textbooks approved by the California Department of Education ignore and omit the history of the California Genocide. Although many historians have strongly pushed for recognition of the genocide in public school curricula, government-approved textbooks deny it because of the dominance of conservative publishing companies with ideological impetus to deny the genocide, the fear of publishing companies being branded as un-American for discussing the genocide, and the unwillingness of state and federal government officials to acknowledge the genocide due to the possibility of having to pay reparations to indigenous communities affected by it.

War crimes

Japanese war crimes

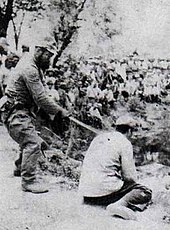

The post-war minimization of the war crimes of Japanese imperialism is an example of "illegitimate" historical revisionism; some contemporary Japanese revisionists, such as Yūko Iwanami (granddaughter of General Hideki Tojo), propose that Japan's invasion of China, and World War II, itself, were justified reactions to the racist Western imperialism of the time. On 2 March 2007, Japanese prime minister Shinzō Abe denied that the military had forced women into sexual slavery during the war, saying, "The fact is, there is no evidence to prove there was coercion". Before he spoke, some Liberal Democratic Party legislators also sought to revise Yōhei Kōno's apology to former comfort women in 1993; likewise, there was the controversial negation of the six-week Nanking Massacre in 1937–1938.

Shinzō Abe led the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform and headed the Diet antenna of Nippon Kaigi, two openly revisionist groups denying Japanese war crimes. Editor-in-chief of the conservative Yomiuri Shimbun Tsuneo Watanabe criticized the Yasukuni Shrine as a bastion of revisionism: "The Yasukuni Shrine runs a museum where they show items in order to encourage and worship militarism. It's wrong for the prime minister to visit such a place". Other critics note that men, who would contemporarily be perceived as "Korean" and "Chinese", are enshrined for the military actions they effected as Japanese Imperial subjects.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings

The Hibakusha ("explosion-affected people") of Hiroshima and Nagasaki seek compensation from their government and criticize it for failing to "accept responsibility for having instigated and then prolonged an aggressive war long after Japan's defeat was apparent, resulting in a heavy toll in Japanese, Asian and American lives". Historians Hill and Koshiro have stated that attempts to minimize the importance of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is revisionist history. EB Sledge expressed concern that such revisionism, in his words "mellowing", would allow the harsh facts of the history that led to the bombings to be forgotten.

Croatian war crimes in World War II

Some Croats, including some high-ranked officials and political leaders during the 1990s and far-right organization members, have attempted to minimize the magnitude of the genocide perpetrated against Serbs and other ethnic minorities in the World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, the Independent State of Croatia. By 1989, the future President of Croatia Franjo Tuđman (who had been a Partisan during World War II), had embraced Croatian nationalism and published Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy, in which he questioned the official number of victims killed by the Ustaše during the Second World War, particularly at the Jasenovac concentration camp. Yugoslav and Serbian historiography had long exaggerated the number of victims at the camp. Tuđman criticized the long-standing figures, but also described the camp as a "work camp", giving an estimate of between 30,000 and 40,000 deaths. Tuđman's government's toleration of Ustaša symbols and their crimes often dismissed in public, frequently strained relations with Israel.

Croatia's far-right often advocates the false theory that Jasenovac was a "labour camp" where mass murder did not take place. In 2017, two videos of former Croatian president Stjepan Mesić from 1992 were made public in which he stated that Jasenovac wasn't a death camp. The far-right NGO "The Society for Research of the Threefold Jasenovac Camp" also advocates this disproven theory, in addition to claiming that the camp was used by the Yugoslav authorities following the war to imprison Ustasha members and regular Home Guard army troops until 1948, then alleged Stalinists until 1951. Its members include journalist Igor Vukić, who wrote his own book advocating the theory, Catholic priest Stjepan Razum and academic Josip Pečarić. The ideas promoted by its members have been amplified by mainstream media interviews and book tours. The last book, "The Jasenovac Lie Revealed" written by Vukić, prompted the Simon Wiesenthal Center to urge Croatian authorities to ban such works, noting that they "would immediately be banned in Germany and Austria and rightfully so". In 2016, Croatian filmmaker Jakov Sedlar released a documentary Jasenovac – The Truth which advocated the same theories, labeling the camp as a "collection and labour camp". The film contained alleged falsifications and forgeries, in addition to denial of crimes and hate speech towards politicians and journalists.

Serbian war crimes in World War II

Among far-right and nationalist groups, denial and revisionism of Serbian war crimes are carried out through the downplaying of Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić's roles in the extermination of Serbia's Jews in concentration camps, in the German-occupied territory of Serbia by a number of Serbian historians. Serbian collaborationist armed forces were involved, either directly or indirectly, in the mass killings of Jews as well as Roma and those Serbs who sided with any anti-German resistance and the killing of many Croats and Muslims. Since the end of the war, Serbian collaboration in the Holocaust has been the subject of historical revisionism by Serbian leaders. In 1993, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts listed Nedić among The 100 most prominent Serbs. There is also the denial of Chetnik collaboration with Axis forces and crimes committed during World War II. Serbian historian Jelena Djureinovic poists in her book The Politics of Memory of the Second World War in Contemporary Serbia: Collaboration, Resistance and Retribution that "during those years, the WWII nationalist Chetniks have been recast as an anti-fascist movement equivalent to Tito's Partisans, and as victims of communism". The glorification of the Chetnik movement has now become the central theme of Serbia's WWII memory politics. Chetnik leaders convicted under communist rule of collaboration with the Nazis have been rehabilitated by Serbian courts, and television programmes have contributed to spreading a positive image of the movement, "distorting the real picture of what happened during WWII".

Serbian war crimes in the Yugoslav wars

There have been a number of far-right and nationalist authors and political activists who have publicly disagreed with mainstream views of Serbian war crimes in the Yugoslav wars of 1991–1999. Some high-ranked Serbian officials and political leaders who categorically claimed that no genocide against Bosnian Muslims took place at all, include former president of Serbia Tomislav Nikolić, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, Serbian Minister of Defence Aleksandar Vulin and Serbian far-right leader Vojislav Šešelj. Among the points of contention are whether the victims of massacres such as the Račak massacre and Srebrenica massacre were unarmed civilians or armed resistance fighters, whether death and rape tolls were inflated, and whether prison camps such as Sremska Mitrovica camp were sites of mass war crimes. These authors are called "revisionists" by scholars and organizations, such as ICTY.

The Report about Case Srebrenica by Darko Trifunovic, commissioned by the government of the Republika Srpska, was described by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia as "one of the worst examples of revisionism in relation to the mass executions of Bosnian Muslims committed in Srebrenica in July 1995". Outrage and condemnation by a wide variety of Balkan and international figures eventually forced the Republika Srpska to disown the report. In 2017 legislation that banned the teaching of the Srebrenica genocide and Sarajevo siege in schools was introduced in Republika Srpska, initiated by President Milorad Dodik and his SNSD party, who stated that it was "impossible to use here the textbooks … which say the Serbs have committed genocide and kept Sarajevo under siege. This is not correct and this will not be taught here". In 2019 Republika Srpska authorities appointed Israeli historian Gideon Greif – who has worked at Yad Vashem for more than three decades - to head its own revisionist commission to "determine the truth" about Srebrenica.

Turkey and the Armenian genocide

Turkish laws such as Article 301, that state "a person who publicly insults Turkishness, or the Republic or [the] Turkish Grand National Assembly of Turkey, shall be punishable by imprisonment", were used to criminally charge the writer Orhan Pamuk with disrespecting Turkey, for saying that "Thirty thousand Kurds, and a million Armenians, were killed in these lands, and nobody, but me, dares to talk about it". The controversy occurred as Turkey was first vying for membership in the European Union (EU) where the suppression of dissenters is looked down upon. Article 301 originally was part of penal-law reforms meant to modernize Turkey to EU standards, as part of negotiating Turkey's membership to the EU. In 2006, the charges were dropped due to pressure from the European Union and United States on the Turkish government.

On 7 February 2006, five journalists were tried for insulting the judicial institutions of the State, and for aiming to prejudice a court case (per Article 288 of the Turkish penal code). The reporters were on trial for criticizing the court-ordered closing of a conference in Istanbul regarding the Armenian genocide during the time of the Ottoman Empire. The conference continued elsewhere, transferring locations from a state to a private university. The trial continued until 11 April 2006, when four of the reporters were acquitted. The case against the fifth journalist, Murat Belge, proceeded until 8 June 2006, when he was also acquitted. The purpose of the conference was to critically analyse the official Turkish view of the Armenian genocide in 1915; a taboo subject in Turkey. The trial proved to be a test case between Turkey and the European Union; the EU insisted that Turkey should allow increased freedom of expression rights, as a condition to membership.

Soviet history

During the existence of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1917–1991) and the Soviet Union (1922–1991), the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) attempted to ideologically and politically control the writing of both academic and popular history. These attempts were most successful in the 1934–1952 period. According to Klaus Mehnert, the Soviets attempt to control academic historiography (the writing of history by academic historians) to promote ideological and ethno-racial imperialism by Russians. During the 1928–1956 period, modern and contemporary history was generally composed according to the wishes of the CPSU, not the requirements of accepted historiographic method.

During and after the rule of Nikita Khrushchev (1956–1964), Soviet historiographic practice was more complicated. Although not entirely corrupted, Soviet historiography was characterized by complex competition between Stalinist and anti-Stalinist Marxist historians. To avoid the professional hazard of politicized history, some historians chose pre-modern, medieval history or classical history, where ideological demands were relatively relaxed and conversation with other historians in the field could be fostered; nevertheless, despite the potential danger of proscribed ideology corrupting historians' work, not all of Soviet historiography was corrupt. Control over party history and the legal status of individual ex-party members played a large role in dictating the ideological diversity and thus the faction in power within the CPSU. The history of the Communist Party was revised to delete references to leaders purged from the party, especially during the rule of Joseph Stalin (1922–1953).

In the historiography of the Cold War, a controversy over negationist historical revisionism exists, where numerous revisionist scholars in the West have been accused of whitewashing the crimes of Stalinism, overlooking the Katyn massacre in Poland, disregarding the validity of the Venona messages with regards to Soviet espionage in the United States, as well as the denial of the Ukrainian Famine that took place during 1932–1933 (also known as denial of the Holodomor).

Azerbaijan

In relation to Armenia

Many scholars, among them Victor Schnirelmann, Willem Floor, Robert Hewsen, George Bournoutian and others state that in Soviet and post-Soviet Azerbaijan since the 1960s there is a practice of revising primary sources on the South Caucasus in which any mention about Armenians is removed. In the revised texts, Armenian is either simply removed or is replaced by Albanian; there are many other examples of such falsifications, all of which have the purpose of creating an impression that historically Armenians were not present in this territory. Willem M. Floor and Hasan Javadi in the English edition of "The Heavenly Rose-Garden: A History of Shirvan & Daghestan" by Abbasgulu Bakikhanov specifically point out to the instances of distortions and falsifications made by Ziya Bunyadov in his Russian translation of this book. According to Bournoutian and Hewsen these distortions are widespread in these works; they thus advise the readers in general to avoid the books produced in Azerbaijan in Soviet and post-Soviet times if these books do not contain the facsimile copy of original sources. Shnirelman thinks that this practice is being realized in Azerbaijan according to state order. Philip L. Kohl brings an example of a theory advanced by Azerbaijani archeologist Akhundov about Albanian origin of Khachkars as an example of patently false cultural origin myths.

The Armenian cemetery in Julfa, a cemetery near the town of Julfa, in the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan originally housed around 10,000 funerary monuments. The tombstones consisted mainly of thousands of khachkars, uniquely decorated cross-stones characteristic of medieval Christian Armenian art. The cemetery was still standing in the late 1990s, when the government of Azerbaijan began a systematic campaign to destroy the monuments. After studying and comparing satellite photos of Julfa taken in 2003 and 2009, the American Association for the Advancement of Science came to the conclusion in December 2010 that the cemetery was demolished and leveled. After the director of the Hermitage Museum Mikhail Piotrovsky expressed his protest about the destruction of Armenian khachkars in Julfa, he was accused by Azerbaijanis of supporting the "total falsification of the history and culture of Azerbaijan". Several appeals were filed by both Armenian and international organizations, condemning the Azerbaijani government and calling on it to desist from such activity. In 2006, Azerbaijan barred European Parliament members from investigating the claims, charging them with a "biased and hysterical approach" to the issue and stating that it would only accept a delegation if it visited Armenian-occupied territory as well. In the spring of 2006, a journalist from the Institute for War and Peace Reporting who visited the area reported that no visible traces of the cemetery remained. In the same year, photographs taken from Iran showed that the cemetery site had been turned into a military shooting range. The destruction of the cemetery has been widely described by Armenian sources, and some non-Armenian sources, as an act of "cultural genocide."

In Azerbaijan, the Armenian genocide is officially denied and is considered a hoax. According to the state ideology of Azerbaijan, a genocide of Azerbaijanis, carried out by Armenians and Russians, took place starting from 1813. Mahmudov has claimed that Armenians first appeared in Karabakh in 1828. Azerbaijani academics and politicians have claimed that foreign historians falsify the history of Azerbaijan and criticism was directed towards a Russian documentary about the regions of Karabakh and Nakhchivan and the historical Armenian presence in these areas. According to the institute director of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Yagub Mahmudov, prior to 1918 "there was never an Armenian state in the South Caucasus". According to Mahmudov, Ilham Aliyev's statement in which he said that "Irevan is our [Azerbaijan's] historic land, and we, Azerbaijanis must return to these historic lands", was based "historical facts" and "historical reality". Mahmudov also stated that the claim that Armenian's are the most ancient people in the region is based on propaganda, and said that Armenians are non-natives of the region, having only arrived in the area after Russian victories over Iran and the Ottoman Empire in the first half of the 19th century. The institute director also said: "The Azerbaijani soldier should know that the land under the feet of provocative Armenians is Azerbaijani land. The enemy can never defeat Azerbaijanis on Azerbaijani soil. Those who rule the Armenian state today must fundamentally change their political course. The Armenians cannot defeat us by sitting in our historic city of Irevan."

In relation to Iran

Historic falsifications in Azerbaijan, in relation to Iran and its history, are "backed by state and state backed non-governmental organizational bodies", ranging "from elementary school all the way to the highest level of universities". As a result of the two Russo-Iranian Wars of the 19th century, the border between what is present-day Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan was formed. Although there had not been a historical Azerbaijani state to speak of in history, the demarcation, set at the Aras river, left significant numbers of what were later coined "Azerbaijanis" to the north of the Aras river. During the existence of the Azerbaijan SSR, as a result of Soviet-era historical revionism and myth-building, the notion of a "northern" and "southern" Azerbaijan was formulated and spread throughout the Soviet Union. During the Soviet nation building campaign, any event, both past and present, that had ever occurred in what is the present-day Azerbaijan Republic and Iranian Azerbaijan were rebranded as phenomenons of "Azerbaijani culture". Any Iranian ruler or poet that had lived in the area was assigned to the newly rebranded identity of the Transcaucasian Turkophones, in other words "Azerbaijanis". According to Michael P. Croissant: "It was charged that the "two Azerbaijans", once united, were separated artificially by a conspiracy between imperial Russia and Iran". This notion based on illegitimate historic revisionism suited Soviet political purposes well (based on "anti-imperialism"), and became the basis for irredentism among Azerbaijani nationalists in the last years of the Soviet Union, shortly prior to the establishment of the Azerbaijan Republic in 1991.

In Azerbaijan, periods and aspects of Iranian history are usually claimed as being an "Azerbaijani" product in a distortion of history, and historic Iranian figures, such as the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi are called "Azerbaijanis", contrary to universally acknowledged fact. In the Azerbaijan SSR, forgeries such as an allaged "Turkish divan" and falsified verses were published in order to "Turkify" Nizami Ganjavi. Although this type of irredentism was initially the result the nation building policy of the Soviets, it became an instrument for "biased, pseudo-academic approaches and political speculations" in the nationalistic aspirations of the young Azerbaijan Republic. In the modern Azerbaijan Repuiblic, historiography is written with the aim of retroactively Turkifying many of the peoples and kingdoms that existed prior to the arrival of Turks in the region, including the Iranian Medes. According to professor of history George Bournoutian:

As noted, in order to construct an Azerbaijani national history and identity based on the territorial definition of a nation, as well as to reduce the influence of Islam and Iran, the Azeri nationalists, prompted by Moscow devised an "Azeri" alphabet, which replaced the Arabo-Persian script. In the 1930s a number of Soviet historians, including the prominent Russian Orientalist, Ilya Petrushevskii, were instructed by the Kremlin to accept the totally unsubstantiated notion that the territory of the former Iranian khanates (except Yerevan, which had become Soviet Armenia) was part of an Azerbaijani nation. Petrushevskii's two important studies dealing with the South Caucasus, therefore, use the term Azerbaijan and Azerbaijani in his works on the history of the region from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Other Russian academics went even further and claimed that an Azeri nation had existed from ancient times and had continued to the present. Since all the Russian surveys and almost all nineteenth-century Russian primary sources referred to the Muslims who resided in the South Caucasus as "Tatars" and not "Azerbaijanis", Soviet historians simply substituted Azerbaijani for Tatars. Azeri historians and writers, starting in 1937, followed suit and began to view the three-thousand-year history of the region as that of Azerbaijan. The pre-Iranian, Iranian, and Arab eras were expunged. Anyone who lived in the territory of Soviet Azerbaijan was classified as Azeri; hence the great Iranian poet Nezami, who had written only in Persian, became the national poet of Azerbaijan.

Bournoutian adds:

Although after Stalin's death arguments rose between Azerbaijani historians and Soviet Iranologists dealing with the history of the region in ancient times (specifically the era of the Medes), no Soviet historian dared to question the use of the term Azerbaijan or Azerbaijani in modern times. As late as 1991, the Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, published a book by an Azeri historian, in which it noy only equated the "Tatars" with the present-day Azeris, but the author, discussing the population numbers in 1842, also included Nakhichevan and Ordubad in "Azerbaijan". The author, just like Petrushevskii, totally ignored the fact that between 1828 and 1921, Nakhichivan and Ordubad were first part of the Armenian Province and then part of the Yerevan guberniia and had only become part of Soviet Azerbaijan, some eight decades later ... Although the overwhelming number of nineteenth-century Russian and Iranian, as well as present-day European historians view the Iranian province of Azarbayjan and the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan as two separate geographical and political entities, modern Azeri historians and geographers view it as a single state that has been separated into "northern" and "southern" sectors and which will be united in the future. ... Since the collapse of the Soviet Union the current Azeri historians have not only continued to use the terms "northern" and "southern" Azerbaijan, but also assert that the present-day Armenian Republic was a part of northern Azerbaijan. In their fury over what they view as the "Armenian occupation" of Nagorno-Karabakh [which incidentally was an autonomous Armenian region within Soviet Azerbaijan], Azeri politicians and historians deny any historic Armenian presence in the South Caucasus and add that all Armenian architectural monuments located in the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan are not Armenian but [Caucasian] Albanian.

North Korea and the Korean War

Since the start of the Korean War (1950–53), the government of North Korea has consistently denied that the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) launched the attack with which it began the war for the Communist unification of Korea. The historiography of the DPRK maintains that the war was provoked by South Korea, at the instigation of the United States: "On June 17, Juche 39 [1950] the then U.S. President [Harry S.] Truman sent [John Foster] Dulles as his special envoy to South Korea to examine the anti-North war scenario and give an order to start the attack. On June 18, Dulles inspected the 38th parallel and the war preparations of the 'ROK Army' units. That day he told Syngman Rhee to start the attack on North Korea with the counter-propaganda that North Korea first 'invaded' the south."

Further North Korean pronouncements included the claim that the U.S. needed the peninsula of Korea as "a bridgehead, for invading the Asian continent, and as a strategic base, from which to fight against national-liberation movements and socialism, and, ultimately, to attain world supremacy." Likewise, the DPRK denied the war crimes committed by the North Korean army in the course of the war; nonetheless, in the 1951–1952 period, the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) privately admitted to the "excesses" of their earlier campaign against North Korean citizens who had collaborated with the enemy – either actually or allegedly – during the US–South Korean occupation of North Korea. Later, the WPK blamed every wartime atrocity upon the U.S. military, e.g. the Sinchon Massacre (17 October – 7 December 1950) occurred during the retreat of the DPRK government from Hwanghae Province, in the south-west of North Korea.

The campaign against "collaborators" was attributed to political and ideological manipulations by the U.S.; the high-rank leader Pak Chang-ok said that the American enemy had "started to use a new method, namely, it donned a leftist garb, which considerably influenced the inexperienced cadres of the Party and government organs." Kathryn Weathersby's Soviet Aims in Korea and the Origins of the Korean War, 1945–1950: New Evidence from Russian Archives (1993) confirmed that the Korean War was launched by order of Kim Il-sung (1912–1994); and also refuted the DPRK's allegations of biological warfare in the Korean War. The Korean Central News Agency dismissed the historical record of Soviet documents as "sheer forgery".

Holocaust denial

Holocaust deniers usually reject the term Holocaust denier as an inaccurate description of their historical point of view, instead preferring the term Holocaust revisionist; nonetheless, scholars prefer "Holocaust denier" to differentiate deniers from legitimate historical revisionists, whose goal is to accurately analyse historical evidence with established methods. Historian Alan Berger reports that Holocaust deniers argue in support of a preconceived theory – that the Holocaust either did not occur or was mostly a hoax – by ignoring extensive historical evidence to the contrary.

When the author David Irving lost his English libel case against Deborah Lipstadt, and her publisher, Penguin Books, and thus was publicly discredited and identified as a Holocaust denier, the trial judge, Justice Charles Gray, concluded that "Irving has, for his own ideological reasons, persistently and deliberately misrepresented and manipulated historical evidence; that, for the same reasons, he has portrayed Hitler in an unwarrantedly favorable light, principally in relation to his attitude towards, and responsibility for, the treatment of the Jews; that he is an active Holocaust denier; that he is anti-semitic and racist, and that he associates with right-wing extremists who promote neo-Nazism."

On 20 February 2006, Irving was found guilty, and sentenced to three years imprisonment for Holocaust denial, under Austria's 1947 law banning Nazi revivalism and criminalizing the "public denial, belittling or justification of National Socialist crimes". Besides Austria, eleven other countries – including Belgium, France, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, and Switzerland – have criminalized Holocaust denial as punishable with imprisonment.

Poland

The Act on the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation is a 1998 Polish law that created the Institute of National Remembrance. The 2018 amendment, article 55a, referred to by critics variously as the "Polish Holocaust bill", the "Poland Holocaust law", etc., has caused international controversy. Article 55a banned harming the "good name" of Poland, which critics asserted would stifle debate about Polish collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Systematic efforts have been made by Polish nationalists to exaggerate the number of Poles who were murdered by Nazi Germany. These include the conspiracy theory that the Warsaw concentration camp had been an extermination camp in which 200,000 mainly non-Jewish Poles had been murdered using gas chambers. The Wikipedia article on the camp was edited to reflect these claims, a hoax that lasted for 15 years before the claims were detected and removed.

1989 Tiananmen Square protests

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests were a series of pro-democracy demonstrations that were put down violently on 4 June 1989, by the Chinese government via the People's Liberation Army, resulting in estimated casualties of over 10,000 deaths and 40,000 injured, obtained via later declassified documents.

North Macedonia

According to Eugene N. Borza, the Macedonians are in search of their past to legitimize their unsure present, in the disorder of the Balkan politics. Ivaylo Dichev claims that the Macedonian historiography has the impossible task of filling the huge gaps between the ancient kingdom of Macedon, that collapsed in 2nd century BC, the 10th–11th century state of the Cometopuls, and the Yugoslav Macedonia established in the middle of the 20th century. According to Ulf Brunnbauer, modern Macedonian historiography is highly politicized, because the Macedonian nation-building process is still in development. The recent nation-building project imposes the idea of a "Macedonian nation" with unbroken continuity from the antiquity (Ancient Macedonians) to the modern times, which has been criticized by some domestic and foreign scholars for ahistorically projecting modern ethnic distinctions into the past. In this way generations of students were educated in pseudohistory.

In textbooks

Japan

The history textbook controversy centres upon the secondary school history textbook Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho ("New History Textbook") said to minimize the nature of Japanese militarism in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), in annexing Korea in 1910, in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), and in the Pacific Theater of World War II (1941–45). The conservative Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform commissioned the Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho textbook with the purpose of traditional national and international view of that Japanese historical period. The Ministry of Education vets all history textbooks, and those that do not mention Japanese war crimes and atrocities are not vetted; however, the Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho de-emphasizes aggressive Japanese Imperial wartime behaviour and the matter of Chinese and Korean comfort women. It has even been denied that the Nanking massacre (a series of murders and rapes committed by the Japanese army against Chinese civilians during the Second Sino-Japanese War) ever took place (see Nanking massacre denial). In 2007, the Ministry of Education attempted to revise textbooks regarding the Battle of Okinawa, lessening the involvement of the Japanese military in Okinawan civilian mass suicides.

Pakistan

Allegations of historical revisionism have been made regarding Pakistani textbooks in that they are laced with Indophobic and Islamist bias. Pakistan's use of officially published textbooks has been criticized for using schools to more subtly foster religious extremism, whitewashing Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent and promoting "expansive pan-Islamic imaginings" that "detect the beginnings of Pakistan in the birth of Islam on the Arabian peninsula". Since 2001, the Pakistani government has stated that curriculum reforms have been underway by the Ministry of Education.

South Korea

12 October 2015, South Korea's government has announced controversial plans to control the history textbooks used in secondary schools despite oppositional concerns of people and academics that the decision is made to glorify the history of those who served the Imperial Japanese government (Chinilpa). Section and the authoritarian dictatorships in South Korea during 1960s–1980s.The Ministry of Education announced that it would put the secondary-school history textbook under state control; "This was an inevitable choice in order to straighten out historical errors and end the social dispute caused by ideological bias in the textbooks," Hwang Woo-yea, education minister said on 12 October 2015. According to the government's plan, the current history textbooks of South Korea will be replaced by a single textbook written by a panel of government-appointed historians and the new series of publications would be issued under the title The Correct Textbook of History and are to be issued to the public and private primary and secondary schools in 2017 onwards.

The move has sparked fierce criticism from academics who argue that the system can be used to distort the history and glorify the history of those who served the Imperial Japanese government (Chinilpa) and of the authoritarian dictatorships. Moreover, 466 organizations including Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union formed History Act Network in solidarity and have staged protests: "The government's decision allows the state too much control and power and, therefore, it is against political neutrality that is certainly the fundamental principle of education." Many South Korean historians condemned Kyohaksa for their text glorifying those who served the Imperial Japanese government (Chinilpa) and the authoritarian dictatorship with a far-right political perspective. On the other hand, New Right supporters welcomed the textbook, saying that "the new textbook finally describes historical truths contrary to the history textbooks published by left-wing publishers", and the textbook issue became intensified as a case of ideological conflict. In Korean history, the history textbook was once put under state control during the authoritarian regime under Park Chung-hee (1963–1979), who is a father of Park Geun-hye, former President of South Korea, and was used as a means to keep the Yushin Regime, also known as the Yushin Dictatorship; however, there had been continuous criticisms about the system especially from the 1980s when Korea experienced a dramatic democratic development. In 2003, liberalization of textbook began when the textbooks on Korean modern and contemporary history were published though the Textbook Screening System, which allows textbooks to be published not by a single government body but by many different companies, for the first time.

Turkey

Education in Turkey is centralized, and its policy, administration, and content are each determined by the Turkish government. Textbooks taught in schools are either prepared directly by the Ministry of National Education (MEB) or must be approved by its Instruction and Education Board. In practice, this means that the Turkish government is directly responsible for what textbooks are taught in schools across Turkey. In 2014, Taner Akçam, writing for the Armenian Weekly, discussed 2014–2015 Turkish elementary and middle school textbooks that the MEB had made available on the internet. He found that Turkish history textbooks are filled with the message that Armenians are people "who are incited by foreigners, who aim to break apart the state and the country, and who murdered Turks and Muslims." The Armenian genocide is referred to as the "Armenian matter", and is described as a lie perpetrated to further the perceived hidden agenda of Armenians. Recognition of the Armenian genocide is defined as the "biggest threat to Turkish national security".

Akçam summarized one textbook that claims the Armenians had sided with the Russians during the war. The 1909 Adana massacre, in which as many as 20,000–30,000 Armenians were massacred, is identified as "The Rebellion of Armenians of Adana". According to the book, the Armenian Hnchak and Dashnak organizations instituted rebellions in many parts of Anatolia, and "didn't hesitate to kill Armenians who would not join them," issuing instructions that "if you want to survive you have to kill your neighbor first." Claims highlighted by Akçam: "[The Armenians murdered] many people living in villages, even children, by attacking Turkish villages, which had become defenseless because all the Turkish men were fighting on the war fronts. ... They stabbed the Ottoman forces in the back. They created obstacles for the operations of the Ottoman units by cutting off their supply routes and destroying bridges and roads. ... They spied for Russia and by rebelling in the cities where they were located, they eased the way for the Russian invasion. ... Since the Armenians who engaged in massacres in collaboration with the Russians created a dangerous situation, this law required the migration of [Armenian people] from the towns they were living in to Syria, a safe Ottoman territory. ... Despite being in the midst of war, the Ottoman state took precautions and measures when it came to the Armenians who were migrating. Their tax payments were postponed, they were permitted to take any personal property they wished, government officials were assigned to ensure that they were protected from attacks during the journey and that their needs were met, police stations were established to ensure that their lives and properties were secure."

Similar revisionist claims found in other textbooks by Akçam included that Armenian "back-stabbing" was the reason the Ottomans lost the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 (similar to the post-War German stab-in-the-back myth), that the Hamidian massacres never happened, that the Armenians were armed by the Russians during late World War I to fight the Ottomans (in reality they had already been nearly annihilated from the area by this point), that Armenians killed 600,000 Turks during said war, that the deportation were to save Armenians from other violent Armenian gangs, and that Armenians who were deported were later able to return to Turkey unscathed and reclaim their properties. As of 2015, Turkish textbooks still describe the Armenians as "traitors", call the Armenian genocide a lie and say that the Ottoman Turks "took necessary measures to counter Armenian separatism." Armenians are also characterized as "dishonorable and treacherous," and students are taught that Armenians were forcibly relocated to protect Turkish citizens from attacks.

Yugoslavia

Throughout the post war era, though Tito denounced nationalist sentiments in historiography, those trends continued with Croat and Serbian academics at times accusing each other of misrepresenting each other's histories, especially in relation to the Croat-Nazi alliance. Communist historiography was challenged in the 1980s and a rehabilitation of Serbian nationalism by Serbian historians began. Historians and other members of the intelligentsia belonging to the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) and the Writers Association played a significant role in the explanation of the new historical narrative. The process of writing a "new Serbian history" paralleled alongside the emerging ethno-nationalist mobilization of Serbs with the objective of reorganizing the Yugoslav federation. Using ideas and concepts from Holocaust historiography, Serbian historians alongside church leaders applied it to World War Two Yugoslavia and equated the Serbs with Jews and Croats with Nazi Germans.

Chetniks along with the Ustashe were vilified by Tito era historiography within Yugoslavia. In the 1980s, Serbian historians initiated the process of re-examining the narrative of how World War Two was told in Yugoslavia which was accompanied by the rehabilitation of Četnik leader Draža Mihailović. Monographs relating to Mihailović and the Četnik movement were produced by some younger historians who were ideologically close to it towards the end of the 1990s. Being preoccupied with the era, Serbian historians have looked to vindicate the history of the Chetniks by portraying them as righteous freedom fighters battling the Nazis while removing from history books the ambiguous alliances with the Italians and Germans. Whereas the crimes committed by Chetniks against Croats and Muslims in Serbian historiography are overall "cloaked in silence". During the Milošević era, Serbian history was falsified to obscure the role Serbian collaborators Milan Nedić and Dimitrije Ljotić played in cleansing Serbia's Jewish community, killing them in the country or deporting them to Eastern European concentration camps.

In the 1990s following a massive Western media coverage of the Yugoslav civil war, there was a rise of the publications considering the matter on historical revisionism of former Yugoslavia. One of the most prominent authors on the field of historical revisionism in the 1990s considering the newly emerged republics is Noel Malcolm and his works Bosnia: A Short History (1994) and Kosovo: A Short History (1998), that have seen a robust debate among historians following their release; following the release of the latter, the merits of the book were the subject of an extended debate in Foreign Affairs. Critics said that the book was "marred by his sympathies for its ethnic Albanian separatists, anti-Serbian bias, and illusions about the Balkans". In late 1999, Thomas Emmert of the history faculty of Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota reviewed the book in Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans Online and while praising aspects of the book also asserted that it was "shaped by the author's overriding determination to challenge Serbian myths", that Malcolm was "partisan", and also complained that the book made a "transparent attempt to prove that the main Serbian myths are false". In 2006, a study by Frederick Anscombe looked at issues surrounding scholarship on Kosovo such as Noel Malcolm's work Kosovo: A Short History. Anscombe noted that Malcolm offered a "a detailed critique of the competing versions of Kosovo's history" and that his work marked a "remarkable reversal" of previous acceptance by Western historians of the "Serbian account" regarding the migration of the Serbs (1690) from Kosovo. Malcolm has been criticized for being "anti-Serbian" and selective like the Serbs with the sources, while other more restrained critics note that "his arguments are unconvincing". Anscombe noted that Malcolm, like Serbian and Yugoslav historians who have ignored his conclusions sideline and are unwilling to consider indigenous evidence such as that from the Ottoman archive when composing national history.

French law recognizing colonialism's positive value

On 23 February 2005, the Union for a Popular Movement conservative majority at the French National Assembly voted a law compelling history textbooks and teachers to "acknowledge and recognize in particular the positive role of the French presence abroad, especially in North Africa". It was criticized by historians and teachers, among them Pierre Vidal-Naquet, who refused to recognize the French Parliament's right to influence the way history is written (despite the French Holocaust denial laws, see Loi Gayssot). That law was also challenged by left-wing parties and the former French colonies; critics argued that the law was tantamount to refusing to acknowledge the racism inherent to French colonialism, and that the law proper is a form of historical revisionism.

Marcos martial law negationism in the Philippines

In the Philippines, the biggest examples of historical negationism are linked to the Marcos family dynasty, usually Imelda Marcos, Bongbong Marcos, and Imee Marcos specifically. They have been accused of denying or trivializing the human rights violations during martial law and the plunder of the Philippines' coffers while Ferdinand Marcos was president.

Denial of the Muslim conquest of the Iberian peninsula

A spin-off of the vision of history espoused by the "inclusive Spanish nationalism" built in opposition to the National-Catholic brand of Spanish nationalism, it was first coined by Ignacio Olagüe (a dilettante historian connected to the early Spanish fascism) particularly in the former's 1974 work La revolución islámica en Occidente ("The Islamic revolution in the West"). The negationist postulates of Olagüe were later adopted by certain sectors within Andalusian nationalism. These ideas were resurrected in the early 21st century by the Arabist Emilio González Ferrín.

Ramifications and judicature

Some countries have criminalized historical revisionism of historic events such as the Holocaust. The Council of Europe defines it as the "denial, gross minimisation, approval or justification of genocide or crimes against humanity" (article 6, Additional Protocol to the Convention on cybercrime).

International law

Some council-member states proposed an additional protocol to the Council of Europe Cybercrime Convention, addressing materials and "acts of racist or xenophobic nature committed through computer networks"; it was negotiated from late 2001 to early 2002, and, on 7 November 2002, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers adopted the protocol's final text titled Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cyber-crime, Concerning the Criminalisation of Acts of a Racist and Xenophobic Nature Committed through Computer Systems, ("Protocol"). It opened on 28 January 2003, and became current on 1 March 2006; as of 30 November 2011, 20 States have signed and ratified the Protocol, and 15 others have signed, but not yet ratified it (including Canada and South Africa).

The Protocol requires participant States to criminalize the dissemination of racist and xenophobic material, and of racist and xenophobic threats and insults through computer networks, such as the Internet. Article 6, Section 1 of the Protocol specifically covers Holocaust Denial, and other genocides recognized as such by international courts, established since 1945, by relevant international legal instruments. Section 2 of Article 6 allows a Party to the Protocol, at their discretion, only to prosecute the violator if the crime is committed with the intent to incite hatred or discrimination or violence; or to use a reservation, by allowing a Party not to apply Article 6 – either partly or entirely.[184] The Council of Europe's Explanatory Report of the Protocol says that the "European Court of Human Rights has made it clear that the denial or revision of 'clearly established historical facts – such as the Holocaust – ... would be removed from the protection of Article 10 by Article 17' of the European Convention on Human Rights" (see the Lehideux and Isorni judgement of 23 September 1998).

Two of the English-speaking states in Europe, Ireland and the United Kingdom, have not signed the additional protocol, (the third, Malta, signed on 28 January 2003, but has not yet ratified it). On 8 July 2005 Canada became the only non-European state to sign the convention. They were joined by South Africa in April 2008. The United States government does not believe that the final version of the Protocol is consistent with the United States' First Amendment Constitutional rights and has informed the Council of Europe that the United States will not become a Party to the protocol.

Domestic law

There are domestic laws against negationism and hate speech (which may encompass negationism) in several countries, including:

- Austria (Article I §3 Verbotsgesetz 1947 with its 1992 updates and added paragraph §3h).

- Belgium (Belgian Holocaust denial law).

- Czech Republic.

- France (Gayssot Act).

- Germany (§130(3) of the penal code).

- Hungary.

- Israel.

- Lithuania.

- Luxembourg.

- Poland (Article 55 of the law establishing the Institute of National Remembrance 1998).

- Portugal.

- Romania.

- Slovakia.

- Switzerland (Article 261bis of the Penal Code).

Additionally, the Netherlands considers denying the Holocaust as a hate crime – which is a punishable offence. Wider use of domestic laws include the 1990 French Gayssot Act that prohibits any "racist, anti-Semitic or xenophobic" speech, and the Czech Republic and Ukraine have criminalized the denial and the minimization of Communist-era crimes.

In fiction

In the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) by George Orwell, the government of Oceania continually revises historical records to concord with the contemporary political explanations of The Party. When Oceania is at war with Eurasia, the public records (newspapers, cinema, television) indicate that Oceania has been always at war with Eurasia; yet, when Eurasia and Oceania are no longer fighting each other, the historical records are subjected to negationism; thus, the populace are brainwashed to believe that Oceania and Eurasia always have been allies against Eastasia. The protagonist of the story, Winston Smith, is an editor in the Ministry of Truth, responsible for effecting the continual historical revisionism that will negate the contradictions of the past upon the contemporary world of Oceania. To cope with the psychological stresses of life during wartime, Smith begins a diary, in which he observes that "He who controls the present, controls the past. He who controls the past, controls the future", and so illustrates the principal, ideological purpose of historical negationism.

Franz Kurowski was an extremely prolific right-wing German writer who dedicated his entire career to the production of Nazi military propaganda, followed by post-war military pulp fiction and revisionist histories of World War II, claiming the humane behaviour and innocence of war crimes of the Wehrmacht, glorifying war as a desirable state, while fabricating eyewitness reports of atrocities allegedly committed by the Allies, especially Bomber Command and the air raids on Cologne and Dresden as a planned genocide of the civilian population.