From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Discrete

categories of objects such as faces, body parts, tools, animals and

buildings have been associated with preferential activation in

specialised areas of the cerebral cortex, leading to the suggestion that they may be produced separately in discrete neural regions.

Several such regions have been identified within the visual cortex. The fusiform face area (FFA) was first described by Sergent et al.(1992) who conducted a PET (positron emission tomography)

study on subjects viewing gratings, faces, and objects. Facial

identification exclusively produced increased bilateral activation in

the fusiform gyrus,

highlighting the dissociation between faces and other object

processing. Similar results have also been reported for activation of

the parahippocampal place area (PPA) in response to stimuli depicting places and spatial layouts; and in the extrastriate body area (EBA) in response to human body parts.

Studies of patients with brain damage have revealed pure agnosic disorders that selectively impair recognition of specific object categories. Such agnosic disorders have been reported for faces (prosopagnosia),

living vs. nonliving stimuli, fruits, vegetables, tools, and musical

instruments among others, suggesting that such categories may be

processed independently within the brain.

Object-specific areas have been identified consistently across

subjects and studies, however their responses are not always exclusive.

Martin et al. (1996) found using fMRI that although object-specific responses for tools and animals were found in the left premotor cortex and left medial occipital lobes respectively, identification of both tools and animals produced increased bilateral activation of the ventral temporal lobes.

Thus it appears that tools and animals, at least, are not wholly

processed by discrete brain areas (despite selective impairment) and

alternative theories propose that rather that being object-specific,

cortical regions may show preferential activation as a result of greater

expertise in one category, greater homogeneity between category

members, task-related biases, and attentional preference amongst others.

It may be that the use of distinct brain regions for processing

different object categories results from different processing

requirements necessary for each class. Indeed, Malach et al. (2002)

detail findings that buildings and faces require processing at

different resolutions in order to be recognised - face recognition

requires the analysis of fine detail, while buildings can be recognised

using larger scale feature integration. As a result, faces are

associated with central visual field processing while buildings are

processed more peripherally. Malach et al. (2002) report that points on

the retina

sharing foveal centricity are mapped onto parallel cortical bands and

it therefore follows that object classes that are processed differently

by retinal cells should be represented distinctly within the brain.

Consistently, faces and buildings were found to be processed

independently of each other and in discrete cortical regions suggesting

that processing is facilitated by assigning object categories to

distinct cortical regions according to the level and type of processing

that they require.

Origins

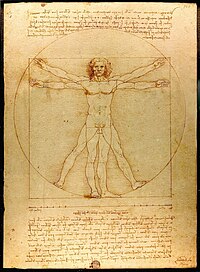

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the philosophy of humanism was a cornerstone of the Enlightenment. Human history was seen as a product of human thought and action, to be understood through the categories of "consciousness", "agency", "choice", "responsibility", "moral values". Human beings were viewed as possessing common essential features. From the belief in a universal moral core of humanity, it followed that all persons were inherently free and equal. For liberal humanists such as Immanuel Kant, the universal law of reason was a guide towards total emancipation from any kind of tyranny.

Criticism of humanism as over-idealistic began in the 19th century. For Friedrich Nietzsche, humanism was nothing more than an empty figure of speech – a secular version of theism. Max Stirner expressed a similar position in his book The Ego and Its Own, published several decades before Nietzsche's work. Nietzsche argues in Genealogy of Morals that human rights

exist as a means for the weak to constrain the strong; as such, they do

not facilitate the emancipation of life, but instead deny it.

The young Marx is sometimes considered a humanist, as he rejected the idea of human rights as a symptom of the very dehumanization they were intended to oppose. Given that capitalism

forces individuals to behave in an egoistic manner, they are in

constant conflict with one another, and are thus in need of rights to

protect themselves. True emancipation, he asserted, could only come

through the establishment of communism, which abolishes private property. According to many anti-humanists, such as Louis Althusser,

mature Marx sees the idea of "humanity" as an unreal abstraction that

masks conflicts between antagonistic classes; since human rights are

abstract, the justice and equality they protect is also abstract,

permitting extreme inequalities in reality.

In the 20th century, the view of humans as rationally autonomous was challenged by Sigmund Freud, who believed humans to be largely driven by unconscious irrational desires.

Martin Heidegger

viewed humanism as a metaphysical philosophy that ascribes to humanity a

universal essence and privileges it above all other forms of existence.

For Heidegger, humanism takes consciousness as the paradigm of philosophy, leading it to a subjectivism and idealism that must be avoided. Like Hegel before him, Heidegger rejected the Kantian notion of autonomy,

pointing out that humans were social and historical beings, as well as

rejecting Kant's notion of a constituting consciousness. In Heidegger's

philosophy, Being (Sein) and human Being (Dasein) are a

primary unity. Dualisms of subject and object, consciousness and being,

humanity and nature are inauthentic derivations from this. In the Letter on Humanism (1947), Heidegger distances himself from both humanism and existentialism.

He argues that existentialism does not overcome metaphysics, as it

merely reverses the basic metaphysical tenet that essence precedes

existence. These metaphysical categories must instead be dismantled.

Positivism and scientism

Positivism is a philosophy of science based on the view that in the social as well as natural sciences, information derived from sensory experience, and logical and mathematical treatments of such data, are together the exclusive source of all authoritative knowledge. Positivism assumes that there is valid knowledge (truth) only in scientific knowledge. Obtaining and verifying data that can be received from the senses is known as empirical evidence.

This view holds that society operates according to general laws that

dictate the existence and interaction of ontologically real objects in

the physical world. Introspective and intuitional attempts to gain

knowledge are rejected. Though the positivist approach has been a

recurrent theme in the history of Western thought, the concept was developed in the modern sense in the early 19th century by the philosopher and founding sociologist, Auguste Comte.

Comte argued that society operates according to its own quasi-absolute

laws, much as the physical world operates according to gravity and other

absolute laws of nature.

Humanist thinker Tzvetan Todorov has identified within modernity a trend of thought which emphasizes science and within it tends towards a deterministic view of the world. He clearly identifies positivist theorist Auguste Comte as an important proponent of this view. For Todorov,

"Scientism

does not eliminate the will but decides that since the results of

science are valid for everyone, this will must be something shared, not

individual. In practice, the individual must submit to the collectivity,

which 'knows' better than he does. The autonomy of the will is

maintained, but it is the will of the group, not the person

[…] scientism has flourished in two very different political contexts

[…] The first variant of scientism was put into practice by totalitarian regimes."

A similar criticism can be found in the work associated with the Frankfurt School of social research. Antipositivism would be further facilitated by rejections of scientism; or science as ideology. Jürgen Habermas argues, in his On the Logic of the Social Sciences (1967), that

"the positivist thesis of unified

science, which assimilates all the sciences to a natural-scientific

model, fails because of the intimate relationship between the social

sciences and history, and the fact that they are based on a

situation-specific understanding of meaning that can be explicated only hermeneutically ... access to a symbolically prestructured reality cannot be gained by observation alone."

Structuralism

Structuralism was developed in post-war Paris as a response to the perceived contradiction between the free subject of philosophy and the determined subject of the human sciences. It drew on the systematic linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure for a view of language and culture as a conventional system of signs preceding the individual subject's entry into them.

In the study of linguistics the structuralists saw an objectivity and

scientificity that contrasted with the humanist emphasis on creativity,

freedom and purpose.

Saussure held that individual units of linguistic signification -

signs - only enjoy their individuality and their power to signify by

virtue of their contrasts or oppositions with other units in the same

symbolic system. For Saussure, the sign is a mysterious unification of a

sound and a thought. Nothing links the two: each sound and thought is

in principle exchangeable for other sounds or concepts. A sign is only

significant as a result of the total system in which it functions. To communicate by particular forms of speech and action (parole) is itself to presuppose a general body of rules (langue).

The concrete piece of behaviour and the system that enables it to mean

something mutually entail each other. The very act of identifying what

they say already implies structures. Signs are thus not at the service

of a subject; they do not pre-exist the relations of difference between

them. We cannot seek an exit from this purely relational system. The

individual is always subordinate to the code. Linguistic study must

abstract from the subjective physical, physiological and psychological

aspects of language to concentrate on langue as a self-contained whole.

The structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss proclaimed that the goal of the human sciences was "not to constitute, but to dissolve man".

He systematised a structuralist analysis of culture that incorporated

ideas and methods from Saussure's model of language as a system of

signifiers and signifieds. His work employed Saussurean technical terms

such as langue and parole, as well as the distinction

between synchronic analysis (abstracting a system as if it were

timeless) and diachronic analysis (where temporal duration is factored

in). He paid little attention to the individual and instead concentrated

on systems of signs as they operated in primitive societies. For

Levi-Strauss, cultural choice was always pre-constrained by a signifying

convention.

Everything in experience was matter for communication codes. The

structure of this system was not devised by anyone and was not present

in the minds of its users, but nonetheless could be discerned by a

scientific observer.

The semiological work of Roland Barthes (1977) decried the cult of the author and indeed proclaimed his death.

Jacques Lacan's reformulation of psychoanalysis

based on linguistics inevitably led to a similar diminishment of the

concept of the autonomous individual: "man with a discourse on freedom

which must certainly be called delusional...produced as it is by an

animal at the mercy of language".

According to Lacan, an individual is not born human but only becomes so

through incorporation into a cultural order that Lacan terms The Symbolic. Access to this order proceeds by way of a "mirror stage", where a child models itself upon its own reflection in a mirror. Language allows us to impose order on our desires at this "Imaginary" stage of development. The unconscious,

which exists prior to this Symbolic Order, must submit to the Symbolic

Law. Since the unconscious is only accessible to the psychoanalyst in

language, the most he or she can do is decode the conscious statements

of the patient. This decoding can only take place within a signifying

chain; the signified of unconscious discourse remains unattainable. It

resides in a pre-signified dimension inaccessible to language that Lacan

calls "The Real". From this, it follows that it is impossible to express subjectivity. Conscious discourse is the effect of a meaning beyond the reach of a speaking subject. The ego is a fiction that covers over a series of effects arrived at independently of the mind itself.

Taking a lead from Brecht's twin attack on bourgeois and socialist humanism, structural Marxist Louis Althusser used the term "antihumanism" in an attack against Marxist humanists, whose position he considered a revisionist movement. He believed humanism to be a bourgeois individualist philosophy that posits a "human essence" through which there is potential for authenticity and common human purpose.

This essence does not exist: it is a formal structure of thought whose

content is determined by the dominant interests of each historical

epoch. Socialist humanism is similarly an ethical and thus ideological

phenomenon. Since its argument rests on a moral and ethical basis, it

reflects the reality of exploitation and discrimination that gives rise

to it but never truly grasps this reality in thought. Marxist theory

must go beyond this to a scientific analysis that directs to underlying

forces such as economic relations and social institutions.

Althusser considered "structure" and "social relations" to have primacy over individual consciousness, opposing the philosophy of the subject. For Althusser, individuals are not constitutive of the social process, but are instead its supports or effects. Society constructs the individual in its own image through its ideologies:

the beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements of the human

individual are the effects of social practices. Where Marxist humanists

such as Georg Lukács believed revolution was contingent on the development of the class consciousness of an historical subject - the proletariat - Althusser's antihumanism removed the role of human agency; history was a process without a subject.

Post-structuralism

Post-structuralist Jacques Derrida

continued structuralism's focus on language as key to understanding all

aspects of individual and social being, as well as its problematization

of the human subject, but rejected its commitment to scientific

objectivity.

Derrida argued that if signs of language are only significant by virtue

of their relations of difference with all other signs in the same

system, then meaning is based purely on the play of differences, and is

never truly present.

He claimed that the fundamentally ambiguous nature of language makes

human intention unknowable, attacked Enlightenment perfectionism, and

condemned as futile the existentialist quest for authenticity in the

face of the all-embracing network of signs. The world itself is text; a

reference to a pure meaning prior to language cannot be expressed in it. As he stressed, "the subject is not some meta-linguistic substance or identity, some pure cogito of self-presence; it is always inscribed in language".

Michel Foucault challenged the foundational aspects of Enlightenment humanism. He rejected absolute categories of epistemology

(truth or certainty) and philosophical anthropology (the subject,

influence, tradition, class consciousness), in a manner not unlike

Nietzsche's earlier dismissal of the categories of reason, morality,

spirit, ego, motivation as philosophical substitutes for God.

Foucault argued that modern values either produced counter-emancipatory

results directly, or matched increased "freedom" with increased and

disciplinary normatization.

His anti-humanist skepticism extended to attempts to ground theory in

human feeling, as much as in human reason, maintaining that both were

historically contingent constructs, rather than the universals humanism

maintained. In The Archaeology of Knowledge,

Foucault dismissed history as "humanist anthropology". The methodology

of his work focused not on the reality that lies behind the categories

of "insanity", "criminality", "delinquency" and "sexuality", but on how

these ideas were constructed by discourses.

Cultural examples

The heroine of the novel Nice Work

begins by defining herself as a semiotic materialist, "a subject

position in an infinite web of discourses – the discourses of power,

sex, family, science, religion, poetry, etc."

Charged with taking a bleak deterministic view, she retorts,

"antihumanist, yes; inhuman, no...the truly determined subject is he who

is not aware of the discursive formations that determine him".

However, with greater life-experience, she comes closer to accepting

that post-structuralism is an intriguing philosophical game, but

probably meaningless to those who have not yet even gained awareness of

humanism itself.

In his critique of humanist approaches to popular film, Timothy Laurie suggests that in new animated films from DreamWorks and Pixar

"the 'human' is now able to become a site of amoral disturbance, rather

than – or at least, in addition to – being a model of exemplary

behaviour for junior audiences".

Origins

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the philosophy of humanism was a cornerstone of the Enlightenment. Human history was seen as a product of human thought and action, to be understood through the categories of "consciousness", "agency", "choice", "responsibility", "moral values". Human beings were viewed as possessing common essential features. From the belief in a universal moral core of humanity, it followed that all persons were inherently free and equal. For liberal humanists such as Immanuel Kant, the universal law of reason was a guide towards total emancipation from any kind of tyranny.

Criticism of humanism as over-idealistic began in the 19th century. For Friedrich Nietzsche, humanism was nothing more than an empty figure of speech – a secular version of theism. Max Stirner expressed a similar position in his book The Ego and Its Own, published several decades before Nietzsche's work. Nietzsche argues in Genealogy of Morals that human rights

exist as a means for the weak to constrain the strong; as such, they do

not facilitate the emancipation of life, but instead deny it.

The young Marx is sometimes considered a humanist, as he rejected the idea of human rights as a symptom of the very dehumanization they were intended to oppose. Given that capitalism

forces individuals to behave in an egoistic manner, they are in

constant conflict with one another, and are thus in need of rights to

protect themselves. True emancipation, he asserted, could only come

through the establishment of communism, which abolishes private property. According to many anti-humanists, such as Louis Althusser,

mature Marx sees the idea of "humanity" as an unreal abstraction that

masks conflicts between antagonistic classes; since human rights are

abstract, the justice and equality they protect is also abstract,

permitting extreme inequalities in reality.

In the 20th century, the view of humans as rationally autonomous was challenged by Sigmund Freud, who believed humans to be largely driven by unconscious irrational desires.

Martin Heidegger

viewed humanism as a metaphysical philosophy that ascribes to humanity a

universal essence and privileges it above all other forms of existence.

For Heidegger, humanism takes consciousness as the paradigm of philosophy, leading it to a subjectivism and idealism that must be avoided. Like Hegel before him, Heidegger rejected the Kantian notion of autonomy,

pointing out that humans were social and historical beings, as well as

rejecting Kant's notion of a constituting consciousness. In Heidegger's

philosophy, Being (Sein) and human Being (Dasein) are a

primary unity. Dualisms of subject and object, consciousness and being,

humanity and nature are inauthentic derivations from this. In the Letter on Humanism (1947), Heidegger distances himself from both humanism and existentialism.

He argues that existentialism does not overcome metaphysics, as it

merely reverses the basic metaphysical tenet that essence precedes

existence. These metaphysical categories must instead be dismantled.

Positivism and scientism

Positivism is a philosophy of science based on the view that in the social as well as natural sciences, information derived from sensory experience, and logical and mathematical treatments of such data, are together the exclusive source of all authoritative knowledge. Positivism assumes that there is valid knowledge (truth) only in scientific knowledge. Obtaining and verifying data that can be received from the senses is known as empirical evidence.

This view holds that society operates according to general laws that

dictate the existence and interaction of ontologically real objects in

the physical world. Introspective and intuitional attempts to gain

knowledge are rejected. Though the positivist approach has been a

recurrent theme in the history of Western thought, the concept was developed in the modern sense in the early 19th century by the philosopher and founding sociologist, Auguste Comte.

Comte argued that society operates according to its own quasi-absolute

laws, much as the physical world operates according to gravity and other

absolute laws of nature.

Humanist thinker Tzvetan Todorov has identified within modernity a trend of thought which emphasizes science and within it tends towards a deterministic view of the world. He clearly identifies positivist theorist Auguste Comte as an important proponent of this view. For Todorov,

"Scientism

does not eliminate the will but decides that since the results of

science are valid for everyone, this will must be something shared, not

individual. In practice, the individual must submit to the collectivity,

which 'knows' better than he does. The autonomy of the will is

maintained, but it is the will of the group, not the person

[…] scientism has flourished in two very different political contexts

[…] The first variant of scientism was put into practice by totalitarian regimes."

A similar criticism can be found in the work associated with the Frankfurt School of social research. Antipositivism would be further facilitated by rejections of scientism; or science as ideology. Jürgen Habermas argues, in his On the Logic of the Social Sciences (1967), that

"the positivist thesis of unified

science, which assimilates all the sciences to a natural-scientific

model, fails because of the intimate relationship between the social

sciences and history, and the fact that they are based on a

situation-specific understanding of meaning that can be explicated only hermeneutically ... access to a symbolically prestructured reality cannot be gained by observation alone."

Structuralism

Structuralism was developed in post-war Paris as a response to the perceived contradiction between the free subject of philosophy and the determined subject of the human sciences. It drew on the systematic linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure for a view of language and culture as a conventional system of signs preceding the individual subject's entry into them.

In the study of linguistics the structuralists saw an objectivity and

scientificity that contrasted with the humanist emphasis on creativity,

freedom and purpose.

Saussure held that individual units of linguistic signification -

signs - only enjoy their individuality and their power to signify by

virtue of their contrasts or oppositions with other units in the same

symbolic system. For Saussure, the sign is a mysterious unification of a

sound and a thought. Nothing links the two: each sound and thought is

in principle exchangeable for other sounds or concepts. A sign is only

significant as a result of the total system in which it functions. To communicate by particular forms of speech and action (parole) is itself to presuppose a general body of rules (langue).

The concrete piece of behaviour and the system that enables it to mean

something mutually entail each other. The very act of identifying what

they say already implies structures. Signs are thus not at the service

of a subject; they do not pre-exist the relations of difference between

them. We cannot seek an exit from this purely relational system. The

individual is always subordinate to the code. Linguistic study must

abstract from the subjective physical, physiological and psychological

aspects of language to concentrate on langue as a self-contained whole.

The structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss proclaimed that the goal of the human sciences was "not to constitute, but to dissolve man".

He systematised a structuralist analysis of culture that incorporated

ideas and methods from Saussure's model of language as a system of

signifiers and signifieds. His work employed Saussurean technical terms

such as langue and parole, as well as the distinction

between synchronic analysis (abstracting a system as if it were

timeless) and diachronic analysis (where temporal duration is factored

in). He paid little attention to the individual and instead concentrated

on systems of signs as they operated in primitive societies. For

Levi-Strauss, cultural choice was always pre-constrained by a signifying

convention.

Everything in experience was matter for communication codes. The

structure of this system was not devised by anyone and was not present

in the minds of its users, but nonetheless could be discerned by a

scientific observer.

The semiological work of Roland Barthes (1977) decried the cult of the author and indeed proclaimed his death.

Jacques Lacan's reformulation of psychoanalysis

based on linguistics inevitably led to a similar diminishment of the

concept of the autonomous individual: "man with a discourse on freedom

which must certainly be called delusional...produced as it is by an

animal at the mercy of language".

According to Lacan, an individual is not born human but only becomes so

through incorporation into a cultural order that Lacan terms The Symbolic. Access to this order proceeds by way of a "mirror stage", where a child models itself upon its own reflection in a mirror. Language allows us to impose order on our desires at this "Imaginary" stage of development. The unconscious,

which exists prior to this Symbolic Order, must submit to the Symbolic

Law. Since the unconscious is only accessible to the psychoanalyst in

language, the most he or she can do is decode the conscious statements

of the patient. This decoding can only take place within a signifying

chain; the signified of unconscious discourse remains unattainable. It

resides in a pre-signified dimension inaccessible to language that Lacan

calls "The Real". From this, it follows that it is impossible to express subjectivity. Conscious discourse is the effect of a meaning beyond the reach of a speaking subject. The ego is a fiction that covers over a series of effects arrived at independently of the mind itself.

Taking a lead from Brecht's twin attack on bourgeois and socialist humanism, structural Marxist Louis Althusser used the term "antihumanism" in an attack against Marxist humanists, whose position he considered a revisionist movement. He believed humanism to be a bourgeois individualist philosophy that posits a "human essence" through which there is potential for authenticity and common human purpose.

This essence does not exist: it is a formal structure of thought whose

content is determined by the dominant interests of each historical

epoch. Socialist humanism is similarly an ethical and thus ideological

phenomenon. Since its argument rests on a moral and ethical basis, it

reflects the reality of exploitation and discrimination that gives rise

to it but never truly grasps this reality in thought. Marxist theory

must go beyond this to a scientific analysis that directs to underlying

forces such as economic relations and social institutions.

Althusser considered "structure" and "social relations" to have primacy over individual consciousness, opposing the philosophy of the subject. For Althusser, individuals are not constitutive of the social process, but are instead its supports or effects. Society constructs the individual in its own image through its ideologies:

the beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements of the human

individual are the effects of social practices. Where Marxist humanists

such as Georg Lukács believed revolution was contingent on the development of the class consciousness of an historical subject - the proletariat - Althusser's antihumanism removed the role of human agency; history was a process without a subject.

Post-structuralism

Post-structuralist Jacques Derrida

continued structuralism's focus on language as key to understanding all

aspects of individual and social being, as well as its problematization

of the human subject, but rejected its commitment to scientific

objectivity.

Derrida argued that if signs of language are only significant by virtue

of their relations of difference with all other signs in the same

system, then meaning is based purely on the play of differences, and is

never truly present.

He claimed that the fundamentally ambiguous nature of language makes

human intention unknowable, attacked Enlightenment perfectionism, and

condemned as futile the existentialist quest for authenticity in the

face of the all-embracing network of signs. The world itself is text; a

reference to a pure meaning prior to language cannot be expressed in it. As he stressed, "the subject is not some meta-linguistic substance or identity, some pure cogito of self-presence; it is always inscribed in language".

Michel Foucault challenged the foundational aspects of Enlightenment humanism. He rejected absolute categories of epistemology

(truth or certainty) and philosophical anthropology (the subject,

influence, tradition, class consciousness), in a manner not unlike

Nietzsche's earlier dismissal of the categories of reason, morality,

spirit, ego, motivation as philosophical substitutes for God.

Foucault argued that modern values either produced counter-emancipatory

results directly, or matched increased "freedom" with increased and

disciplinary normatization.

His anti-humanist skepticism extended to attempts to ground theory in

human feeling, as much as in human reason, maintaining that both were

historically contingent constructs, rather than the universals humanism

maintained. In The Archaeology of Knowledge,

Foucault dismissed history as "humanist anthropology". The methodology

of his work focused not on the reality that lies behind the categories

of "insanity", "criminality", "delinquency" and "sexuality", but on how

these ideas were constructed by discourses.

Cultural examples

The heroine of the novel Nice Work

begins by defining herself as a semiotic materialist, "a subject

position in an infinite web of discourses – the discourses of power,

sex, family, science, religion, poetry, etc."

Charged with taking a bleak deterministic view, she retorts,

"antihumanist, yes; inhuman, no...the truly determined subject is he who

is not aware of the discursive formations that determine him".

However, with greater life-experience, she comes closer to accepting

that post-structuralism is an intriguing philosophical game, but

probably meaningless to those who have not yet even gained awareness of

humanism itself.

In his critique of humanist approaches to popular film, Timothy Laurie suggests that in new animated films from DreamWorks and Pixar

"the 'human' is now able to become a site of amoral disturbance, rather

than – or at least, in addition to – being a model of exemplary

behaviour for junior audiences".