| Transcription factor glossary | |

|---|---|

|

|

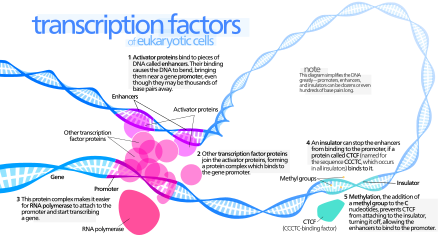

Illustration of an activator

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence.[1][2] The function of TFs is to regulate - turn on and off - genes in order to make sure that they are expressed in the right cell at the right time and in the right amount throughout the life of the cell and the organism. Groups of TFs function in a coordinated fashion to direct cell division, cell growth, and cell death throughout life; cell migration and organization (body plan) during embryonic development; and intermittently in response to signals from outside the cell, such as a hormone. There are up to 2600 TFs in the human genome.

TFs work alone or with other proteins in a complex, by promoting (as an activator), or blocking (as a repressor) the recruitment of RNA polymerase (the enzyme that performs the transcription of genetic information from DNA to RNA) to specific genes.[3][4][5]

A defining feature of TFs is that they contain at least one DNA-binding domain (DBD), which attaches to a specific sequence of DNA adjacent to the genes that they regulate.[6][7] TFs are grouped into classes based on their DBDs.[8][9] Other proteins such as coactivators, chromatin remodelers, histone acetyltransferases, histone deacetylases, kinases, and methylases are also essential to gene regulation, but lack DNA-binding domains, and therefore are not TFs.[10]

TFs are of interest in medicine because TF mutations can cause specific diseases, and medications can be potentially targeted toward them.

Number

Transcription factors are essential for the regulation of gene expression and are, as a consequence, found in all living organisms. The number of transcription factors found within an organism increases with genome size, and larger genomes tend to have more transcription factors per gene.[11]There are approximately 2600 proteins in the human genome that contain DNA-binding domains, and most of these are presumed to function as transcription factors,[12] though other studies indicate it to be a smaller number.[13] Therefore, approximately 10% of genes in the genome code for transcription factors, which makes this family the single largest family of human proteins. Furthermore, genes are often flanked by several binding sites for distinct transcription factors, and efficient expression of each of these genes requires the cooperative action of several different transcription factors (see, for example, hepatocyte nuclear factors). Hence, the combinatorial use of a subset of the approximately 2000 human transcription factors easily accounts for the unique regulation of each gene in the human genome during development.[10]

Mechanism

Transcription factors bind to either enhancer or promoter regions of DNA adjacent to the genes that they regulate. Depending on the transcription factor, the transcription of the adjacent gene is either up- or down-regulated. Transcription factors use a variety of mechanisms for the regulation of gene expression.[14] These mechanisms include:- stabilize or block the binding of RNA polymerase to DNA

- catalyze the acetylation or deacetylation of histone

proteins. The transcription factor can either do this directly or

recruit other proteins with this catalytic activity. Many transcription

factors use one or the other of two opposing mechanisms to regulate

transcription:[15]

- histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity – acetylates histone proteins, which weakens the association of DNA with histones, which make the DNA more accessible to transcription, thereby up-regulating transcription

- histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity – deacetylates histone proteins, which strengthens the association of DNA with histones, which make the DNA less accessible to transcription, thereby down-regulating transcription

- recruit coactivator or corepressor proteins to the transcription factor DNA complex[16]

Function

Transcription factors are one of the groups of proteins that read and interpret the genetic "blueprint" in the DNA. They bind to the DNA and help initiate a program of increased or decreased gene transcription. As such, they are vital for many important cellular processes. Below are some of the important functions and biological roles transcription factors are involved in:Basal transcription regulation

In eukaryotes, an important class of transcription factors called general transcription factors (GTFs) are necessary for transcription to occur.[17][18][19] Many of these GTFs do not actually bind DNA, but rather are part of the large transcription preinitiation complex that interacts with RNA polymerase directly. The most common GTFs are TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID (see also TATA binding protein), TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH.[20] The preinitiation complex binds to promoter regions of DNA upstream to the gene that they regulate.Differential enhancement of transcription

Other transcription factors differentially regulate the expression of various genes by binding to enhancer regions of DNA adjacent to regulated genes. These transcription factors are critical to making sure that genes are expressed in the right cell at the right time and in the right amount, depending on the changing requirements of the organism.Development

Many transcription factors in multicellular organisms are involved in development.[21] Responding to stimuli, these transcription factors turn on/off the transcription of the appropriate genes, which, in turn, allows for changes in cell morphology or activities needed for cell fate determination and cellular differentiation. The Hox transcription factor family, for example, is important for proper body pattern formation in organisms as diverse as fruit flies to humans.[22][23] Another example is the transcription factor encoded by the Sex-determining Region Y (SRY) gene, which plays a major role in determining sex in humans.[24]Response to intercellular signals

Cells can communicate with each other by releasing molecules that produce signaling cascades within another receptive cell. If the signal requires upregulation or downregulation of genes in the recipient cell, often transcription factors will be downstream in the signaling cascade.[25] Estrogen signaling is an example of a fairly short signaling cascade that involves the estrogen receptor transcription factor: Estrogen is secreted by tissues such as the ovaries and placenta, crosses the cell membrane of the recipient cell, and is bound by the estrogen receptor in the cell's cytoplasm. The estrogen receptor then goes to the cell's nucleus and binds to its DNA-binding sites, changing the transcriptional regulation of the associated genes.[26]Response to environment

Not only do transcription factors act downstream of signaling cascades related to biological stimuli but they can also be downstream of signaling cascades involved in environmental stimuli. Examples include heat shock factor (HSF), which upregulates genes necessary for survival at higher temperatures,[27] hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), which upregulates genes necessary for cell survival in low-oxygen environments,[28] and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP), which helps maintain proper lipid levels in the cell.[29]Cell cycle control

Many transcription factors, especially some that are proto-oncogenes or tumor suppressors, help regulate the cell cycle and as such determine how large a cell will get and when it can divide into two daughter cells.[30][31] One example is the Myc oncogene, which has important roles in cell growth and apoptosis.[32]Pathogenesis

Transcription factors can also be used to alter gene expression in a host cell to promote pathogenesis. A well studied example of this are the transcription-activator like effectors (TAL effectors) secreted by Xanthomonas bacteria. When injected into plants, these proteins can enter the nucleus of the plant cell, bind plant promoter sequences, and activate transcription of plant genes that aid in bacterial infection.[33] TAL effectors contain a central repeat region in which there is a simple relationship between the identity of two critical residues in sequential repeats and sequential DNA bases in the TAL effector’s target site.[34][35] This property likely makes it easier for these proteins to evolve in order to better compete with the defense mechanisms of the host cell.[36]Regulation

It is common in biology for important processes to have multiple layers of regulation and control. This is also true with transcription factors: Not only do transcription factors control the rates of transcription to regulate the amounts of gene products (RNA and protein) available to the cell but transcription factors themselves are regulated (often by other transcription factors). Below is a brief synopsis of some of the ways that the activity of transcription factors can be regulated:Synthesis

Transcription factors (like all proteins) are transcribed from a gene on a chromosome into RNA, and then the RNA is translated into protein. Any of these steps can be regulated to affect the production (and thus activity) of a transcription factor. An implication of this is that transcription factors can regulate themselves. For example, in a negative feedback loop, the transcription factor acts as its own repressor: If the transcription factor protein binds the DNA of its own gene, it down-regulates the production of more of itself. This is one mechanism to maintain low levels of a transcription factor in a cell.[37]Nuclear localization

In eukaryotes, transcription factors (like most proteins) are transcribed in the nucleus but are then translated in the cell's cytoplasm. Many proteins that are active in the nucleus contain nuclear localization signals that direct them to the nucleus. But, for many transcription factors, this is a key point in their regulation.[38] Important classes of transcription factors such as some nuclear receptors must first bind a ligand while in the cytoplasm before they can relocate to the nucleus.[38]Activation

Transcription factors may be activated (or deactivated) through their signal-sensing domain by a number of mechanisms including:- ligand binding – Not only is ligand binding able to influence where a transcription factor is located within a cell but ligand binding can also affect whether the transcription factor is in an active state and capable of binding DNA or other cofactors (see, for example, nuclear receptors).

- phosphorylation[39][40] – Many transcription factors such as STAT proteins must be phosphorylated before they can bind DNA.

- interaction with other transcription factors (e.g., homo- or hetero-dimerization) or coregulatory proteins

Accessibility of DNA-binding site

In eukaryotes, DNA is organized with the help of histones into compact particles called nucleosomes, where sequences of about 147 DNA base pairs make ~1.65 turns around histone protein octamers. DNA within nucleosomes is inaccessible to many transcription factors. Some transcription factors, so-called pioneering factors are still able to bind their DNA binding sites on the nucleosomal DNA. For most other transcription factors, the nucleosome should be actively unwound by molecular motors such as chromatin remodelers.[41] Alternatively, the nucleosome can be partially unwrapped by thermal fluctuations, allowing temporary access to the transcription factor binding site. In many cases, a transcription factor needs to compete for binding to its DNA binding site with other transcription factors and histones or non-histone chromatin proteins.[42] Pairs of transcription factors and other proteins can play antagonistic roles (activator versus repressor) in the regulation of the same gene.Availability of other cofactors/transcription factors

Most transcription factors do not work alone. Many large TF families form complex homotypic or heterotypic interactions through dimerization.[43] For gene transcription to occur, a number of transcription factors must bind to DNA regulatory sequences. This collection of transcription factors, in turn, recruit intermediary proteins such as cofactors that allow efficient recruitment of the preinitiation complex and RNA polymerase. Thus, for a single transcription factor to initiate transcription, all of these other proteins must also be present, and the transcription factor must be in a state where it can bind to them if necessary. Cofactors are proteins that modulate the effects of transcription factors. Cofactors are interchangeable between specific gene promoters; the protein complex that occupies the promoter DNA and the amino acid sequence of the cofactor determine its spatial conformation. For example, certain steroid receptors can exchange cofactors with NF-κB, which is a switch between inflammation and cellular differentiation; thereby steroids can affect the inflammatory response and function of certain tissues.[44]Structure

Schematic diagram of the amino acid sequence (amino terminus to the left

and carboxylic acid terminus to the right) of a prototypical

transcription factor that contains (1) a DNA-binding domain (DBD), (2)

signal-sensing domain (SSD), and a transactivation domain (TAD). The

order of placement and the number of domains may differ in various types

of transcription factors. In addition, the transactivation and

signal-sensing functions are frequently contained within the same

domain.

Transcription factors are modular in structure and contain the following domains:[1]

- DNA-binding domain (DBD), which attaches to specific sequences of DNA (enhancer or promoter. Necessary component for all vectors. Used to drive transcription of the vector's transgene promoter sequences) adjacent to regulated genes. DNA sequences that bind transcription factors are often referred to as response elements.

- Trans-activating domain (TAD), which contains binding sites for other proteins such as transcription coregulators. These binding sites are frequently referred to as activation functions (AFs).[45]

- An optional signal-sensing domain (SSD) (e.g., a ligand binding domain), which senses external signals and, in response, transmits these signals to the rest of the transcription complex, resulting in up- or down-regulation of gene expression. Also, the DBD and signal-sensing domains may reside on separate proteins that associate within the transcription complex to regulate gene expression.

Trans-activating domain

TAD is domain of the transcription factor that binds other proteins such as transcription coregulators. Proteins containing TADs are Gal4, Gcn4, Oaf1, Leu3, Rtg3, Pho4, Gln3 in yeast and p53, NFAT, NF-κB and VP16 in mammals.[46] Many TADs are as short as 9 amino acids (present in e.g., p53, VP16, MLL, E2A, HSF1, NF-IL6, NFAT1 and NF-κB Gal4, Pdr1, Oaf1, Gcn4, VP16, Pho4, Msn2, Ino2 and P201).DNA-binding domain

Domain architecture example: Lactose Repressor (LacI). The N-terminal DNA binding domain (labeled) of the lac repressor binds its target DNA sequence (gold) in the major groove using a helix-turn-helix

motif. Effector molecule binding (green) occurs in the core domain

(labeled), a signal sensing domain. This triggers an allosteric response

mediated by the linker region (labeled).

The portion (domain) of the transcription factor that binds DNA is called its DNA-binding domain. Below is a partial list of some of the major families of DNA-binding domains/transcription factors:

| Family | InterPro | Pfam | SCOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| basic helix-loop-helix[47] | InterPro: IPR001092 | Pfam PF00010 | SCOP 47460 |

| basic-leucine zipper (bZIP)[48] | InterPro: IPR004827 | Pfam PF00170 | SCOP 57959 |

| C-terminal effector domain of the bipartite response regulators | InterPro: IPR001789 | Pfam PF00072 | SCOP 46894 |

| AP2/ERF/GCC box | InterPro: IPR001471 | Pfam PF00847 | SCOP 54176 |

| helix-turn-helix[49] | |||

| homeodomain proteins, which are encoded by homeobox genes, are transcription factors. Homeodomain proteins play critical roles in the regulation of development.[50][51] | InterPro: IPR009057 | Pfam PF00046 | SCOP 46689 |

| lambda repressor-like | InterPro: IPR010982 | SCOP 47413 | |

| srf-like (serum response factor) | InterPro: IPR002100 | Pfam PF00319 | SCOP 55455 |

| paired box[52] | |||

| winged helix | InterPro: IPR013196 | Pfam PF08279 | SCOP 46785 |

| zinc fingers[53] | |||

| * multi-domain Cys2His2 zinc fingers[54] | InterPro: IPR007087 | Pfam PF00096 | SCOP 57667 |

| * Zn2/Cys6 | SCOP 57701 | ||

| * Zn2/Cys8 nuclear receptor zinc finger | InterPro: IPR001628 | Pfam PF00105 | SCOP 57716 |

Response elements

The DNA sequence that a transcription factor binds to is called a transcription factor-binding site or response element.[55]Transcription factors interact with their binding sites using a combination of electrostatic (of which hydrogen bonds are a special case) and Van der Waals forces. Due to the nature of these chemical interactions, most transcription factors bind DNA in a sequence specific manner. However, not all bases in the transcription factor-binding site may actually interact with the transcription factor. In addition, some of these interactions may be weaker than others. Thus, transcription factors do not bind just one sequence but are capable of binding a subset of closely related sequences, each with a different strength of interaction.

For example, although the consensus binding site for the TATA-binding protein (TBP) is TATAAAA, the TBP transcription factor can also bind similar sequences such as TATATAT or TATATAA.

Because transcription factors can bind a set of related sequences and these sequences tend to be short, potential transcription factor binding sites can occur by chance if the DNA sequence is long enough. It is unlikely, however, that a transcription factor will bind all compatible sequences in the genome of the cell. Other constraints, such as DNA accessibility in the cell or availability of cofactors may also help dictate where a transcription factor will actually bind. Thus, given the genome sequence it is still difficult to predict where a transcription factor will actually bind in a living cell.

Additional recognition specificity, however, may be obtained through the use of more than one DNA-binding domain (for example tandem DBDs in the same transcription factor or through dimerization of two transcription factors) that bind to two or more adjacent sequences of DNA.

Clinical significance

Transcription factors are of clinical significance for at least two reasons: (1) mutations can be associated with specific diseases, and (2) they can be targets of medications.Disorders

Due to their important roles in development, intercellular signaling, and cell cycle, some human diseases have been associated with mutations in transcription factors.[56]Many transcription factors are either tumor suppressors or oncogenes, and, thus, mutations or aberrant regulation of them is associated with cancer. Three groups of transcription factors are known to be important in human cancer: (1) the NF-kappaB and AP-1 families, (2) the STAT family and (3) the steroid receptors.[57]

Below are a few of the more well-studied examples:

| Condition | Description | Locus |

|---|---|---|

| Rett syndrome | Mutations in the MECP2 transcription factor are associated with Rett syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder.[58][59] | Xq28 |

| Diabetes | A rare form of diabetes called MODY (Maturity onset diabetes of the young) can be caused by mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factors (HNFs)[60] or insulin promoter factor-1 (IPF1/Pdx1).[61] | multiple |

| Developmental verbal dyspraxia | Mutations in the FOXP2 transcription factor are associated with developmental verbal dyspraxia, a disease in which individuals are unable to produce the finely coordinated movements required for speech.[62] | 7q31 |

| Autoimmune diseases | Mutations in the FOXP3 transcription factor cause a rare form of autoimmune disease called IPEX.[63] | Xp11.23-q13.3 |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | Caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor p53.[64] | 17p13.1 |

| Breast cancer | The STAT family is relevant to breast cancer.[65] | multiple |

| Multiple cancers | The HOX family are involved in a variety of cancers.[66] | multiple |

Potential drug targets

Approximately 10% of currently prescribed drugs directly target the nuclear receptor class of transcription factors.[67] Examples include tamoxifen and bicalutamide for the treatment of breast and prostate cancer, respectively, and various types of anti-inflammatory and anabolic steroids.[68] In addition, transcription factors are often indirectly modulated by drugs through signaling cascades. It might be possible to directly target other less-explored transcription factors such as NF-κB with drugs.[69][70][71][72] Transcription factors outside the nuclear receptor family are thought to be more difficult to target with small molecule therapeutics since it is not clear that they are "drugable" but progress has been made on Pax2[73] [74] and the notch pathway.[75]Role in evolution

Gene duplications have played a crucial role in the evolution of species. This applies particularly to transcription factors. Once they occur as duplicates, accumulated mutations encoding for one copy can take place without negatively affecting the regulation of downstream targets. However, changes of the DNA binding specificities of the single-copy LEAFY transcription factor, which occurs in most land plants, have recently been elucidated. In that respect, a single-copy transcription factor can undergo a change of specificity through a promiscuous intermediate without losing function. Similar mechanisms have been proposed in the context of all alternative phylogenetic hypotheses, and the role of transcription factors in the evolution of all species.[76][77]Analysis

There are different technologies available to analyze transcription factors. On the genomic level, DNA-sequencing[78] and database research are commonly used[79] The protein version of the transcription factor is detectable by using specific antibodies. The sample is detected on a western blot. By using electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA),[80] the activation profile of transcription factors can be detected. A multiplex approach for activation profiling is a TF chip system where several different transcription factors can be detected in parallel. This technology is based on DNA microarrays, providing the specific DNA-binding sequence for the transcription factor protein on the array surface.[81]Classes

As described in more detail below, transcription factors may be classified by their (1) mechanism of action, (2) regulatory function, or (3) sequence homology (and hence structural similarity) in their DNA-binding domains.Mechanistic

There are two mechanistic classes of transcription factors:- General transcription factors are involved in the formation of a preinitiation complex. The most common are abbreviated as TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH. They are ubiquitous and interact with the core promoter region surrounding the transcription start site(s) of all class II genes.[82]

- Upstream transcription factors are proteins that bind somewhere upstream of the initiation site to stimulate or repress transcription. These are roughly synonymous with specific transcription factors, because they vary considerably depending on what recognition sequences are present in the proximity of the gene.[83]

| Examples of specific transcription factors[83] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Structural type | Recognition sequence | Binds as |

| SP1 | Zinc finger | 5'-GGGCGG-3' | Monomer |

| AP-1 | Basic zipper | 5'-TGA(G/C)TCA-3' | Dimer |

| C/EBP | Basic zipper | 5'-ATTGCGCAAT-3' | Dimer |

| Heat shock factor | Basic zipper | 5'-XGAAX-3' | Trimer |

| ATF/CREB | Basic zipper | 5'-TGACGTCA-3' | Dimer |

| c-Myc | Basic helix-loop-helix | 5'-CACGTG-3' | Dimer |

| Oct-1 | Helix-turn-helix | 5'-ATGCAAAT-3' | Monomer |

| NF-1 | Novel | 5'-TTGGCXXXXXGCCAA-3' | Dimer |

| (G/C) = G or C X = A, T, G or C |

|||

Functional

Transcription factors have been classified according to their regulatory function:[10]- I. constitutively active – present in all cells at all times – general transcription factors, Sp1, NF1, CCAAT

- II. conditionally active – requires activation

- II.A developmental (cell specific) – expression is tightly controlled, but, once expressed, require no additional activation – GATA, HNF, PIT-1, MyoD, Myf5, Hox, Winged Helix

- II.B signal-dependent – requires external signal for activation

- II.B.1 extracellular ligand (endocrine or paracrine)-dependent – nuclear receptors

- II.B.2 intracellular ligand (autocrine)-dependent - activated by small intracellular molecules – SREBP, p53, orphan nuclear receptors

- II.B.3 cell membrane receptor-dependent – second messenger signaling cascades resulting in the phosphorylation of the transcription factor

Structural

Transcription factors are often classified based on the sequence similarity and hence the tertiary structure of their DNA-binding domains:[84][9][85][8]- 1 Superclass: Basic Domains

- 1.1 Class: Leucine zipper factors (bZIP)

- 1.2 Class: Helix-loop-helix factors (bHLH)

- 1.2.1 Family: Ubiquitous (class A) factors

- 1.2.2 Family: Myogenic transcription factors (MyoD)

- 1.2.3 Family: Achaete-Scute

- 1.2.4 Family: Tal/Twist/Atonal/Hen

- 1.3 Class: Helix-loop-helix / leucine zipper factors (bHLH-ZIP)

- 1.4 Class: NF-1

- 1.5 Class: RF-X

- 1.6 Class: bHSH

- 2 Superclass: Zinc-coordinating DNA-binding domains

- 2.1 Class: Cys4 zinc finger of nuclear receptor type

- 2.1.1 Family: Steroid hormone receptors

- 2.1.2 Family: Thyroid hormone receptor-like factors

- 2.2 Class: diverse Cys4 zinc fingers

- 2.2.1 Family: GATA-Factors

- 2.3 Class: Cys2His2 zinc finger domain

- 2.4 Class: Cys6 cysteine-zinc cluster

- 2.5 Class: Zinc fingers of alternating composition

- 2.1 Class: Cys4 zinc finger of nuclear receptor type

- 3 Superclass: Helix-turn-helix

- 3.1 Class: Homeo domain

- 3.1.1 Family: Homeo domain only; includes Ubx

- 3.1.2 Family: POU domain factors; includes Oct

- 3.1.3 Family: Homeo domain with LIM region

- 3.1.4 Family: homeo domain plus zinc finger motifs

- 3.2 Class: Paired box

- 3.2.1 Family: Paired plus homeo domain

- 3.2.2 Family: Paired domain only

- 3.3 Class: Fork head / winged helix

- 3.3.1 Family: Developmental regulators; includes forkhead

- 3.3.2 Family: Tissue-specific regulators

- 3.3.3 Family: Cell-cycle controlling factors

- 3.3.0 Family: Other regulators

- 3.4 Class: Heat Shock Factors

- 3.4.1 Family: HSF

- 3.5 Class: Tryptophan clusters

- 3.5.1 Family: Myb

- 3.5.2 Family: Ets-type

- 3.5.3 Family: Interferon regulatory factors

- 3.6 Class: TEA ( transcriptional enhancer factor) domain

- 3.1 Class: Homeo domain

- 4 Superclass: beta-Scaffold Factors with Minor Groove Contacts

- 4.1 Class: RHR (Rel homology region)

- 4.2 Class: STAT

- 4.2.1 Family: STAT

- 4.3 Class: p53

- 4.3.1 Family: p53

- 4.4 Class: MADS box

- 4.4.1 Family: Regulators of differentiation; includes (Mef2)

- 4.4.2 Family: Responders to external signals, SRF (serum response factor) (SRF)

- 4.4.3 Family: Metabolic regulators (ARG80)

- 4.5 Class: beta-Barrel alpha-helix transcription factors

- 4.6 Class: TATA binding proteins

- 4.6.1 Family: TBP

- 4.7 Class: HMG-box

- 4.8 Class: Heteromeric CCAAT factors

- 4.8.1 Family: Heteromeric CCAAT factors

- 4.9 Class: Grainyhead

- 4.9.1 Family: Grainyhead

- 4.10 Class: Cold-shock domain factors

- 4.10.1 Family: csd

- 4.11 Class: Runt

- 4.11.1 Family: Runt

- 0 Superclass: Other Transcription Factors