In spirituality, nondualism, also called non-duality, means "not two" or "one undivided without a second". Nondualism primarily refers to a mature state of consciousness, in which the dichotomy of I-other is 'transcended', and awareness is described as 'centerless' and 'without dichotomies'. Although this state of consciousness may seem to appear spontaneous, it usually is the "result" of prolonged ascetic or meditative/contemplative practice, which includes ethical injunctions. While the term "nondualism" is derived from Advaita Vedanta, descriptions of nondual consciousness can be found within Hinduism (Turiya, sahaja), Buddhism (Buddha-nature, rigpa, shentong), and western Christian and neo-Platonic traditions (henosis, mystical union).

The Asian idea of nondualism developed in the Vedic and post-Vedic Hindu philosophies, as well as in the Buddhist traditions.[3] The oldest traces of nondualism in Indian thought are found as Advaita in the earlier Hindu Upanishads such as Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, as well as other pre-Buddhist Upanishads such as the Chandogya Upanishad, which emphasizes the unity of individual soul called Atman and the Supreme called Brahman. In Hinduism, nondualism has more commonly become associated with the Advaita Vedanta tradition of Adi Shankara.[4]

The Buddhist tradition added the teachings of śūnyatā; the two truths doctrine, the nonduality of the absolute and the relative truth,[5][6] and the Yogachara notion of "mind/thought only" (citta-matra) or "representation-only" (vijñaptimātra).[4] Vijñapti-mātra and the two truths doctrine, coupled with the concept of Buddha-nature, have also been influential concepts in the subsequent development of Mahayana Buddhism, not only in India, but also in China and Tibet, most notably the Chán (Zen) and Dzogchen traditions.

Western Neo-Platonism is an essential element of both Christian contemplation and mysticism, and of Western esotericism and modern spirituality, especially Unitarianism, Transcendentalism, Universalism and Perennialism.

Etymology

"Advaita" (अद्वैत) is from Sanskrit roots a, not; dvaita, dual, and is usually translated as "nondualism", "nonduality" and "nondual". The term "nondualism" and the term "advaita" from which it originates are polyvalent terms. The English word's origin is the Latin duo meaning "two" prefixed with "non-" meaning "not".

"Advaya" (अद्वय) is also a Sanskrit word that means "identity, unique, not two, without a second," and typically refers to the two truths doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism, especially Madhyamaka.

One of the earliest usage of the word Advaita is found in verse 4.3.32 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (~800 BCE), and in verses 7 and 12 of the Mandukya Upanishad (variously dated to have been composed between 500 BCE to 200 CE).[7] The term appears in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad in the section with a discourse of the oneness of Atman and Brahman, as follows:[8]

An ocean is that one seer, without any duality [Advaita]; this is the Brahma-world, O King. Thus did Yajnavalkya teach him. This is his highest goal, this is his highest success, this is his highest world, this is his highest bliss. All other creatures live on a small portion of that bliss.The English term "nondual" was also informed by early translations of the Upanishads in Western languages other than English from 1775. These terms have entered the English language from literal English renderings of "advaita" subsequent to the first wave of English translations of the Upanishads. These translations commenced with the work of Müller (1823–1900), in the monumental Sacred Books of the East (1879).

Max Müller rendered "advaita" as "Monism", as have many recent scholars.[12][13][14] However, some scholars state that "advaita" is not really monism.[15]

Definitions

Nondualism is a fuzzy concept, for which many definitions can be found.[note 2]According to Espín and Nickoloff, "nondualism" is the thought in some Hindu, Buddhist and Taoist schools, which

... teaches that the multiplicity of the universe is reducible to one essential reality."[16]According to Jeff Foster,

'Non-duality'[...] points to the essential oneness (wholeness, completeness, unity) of life, a wholeness which exists here and now, prior to any apparent separation [...] despite the compelling appearance of separation and diversity there is only one universal essence, one reality. Oneness is all there is – and we are included.[web 2]Jeff Foster further explains

What you are is simply this open space of awareness (consciousness, awakeness, Being) in which absolutely everything seems to come and go, and that space is already at rest; it’s already Home.[web 2]David Loy, who sees non-duality between subject and object as a common thread in Taoism, Mahayana Buddhism, and Advaita Vedanta,[17][note 3] distinguishes "Five Flavors Of Nonduality":[web 3]

- The negation of dualistic thinking in pairs of opposites. The Yin-Yang symbol of Taoism symbolises the transcendence of this dualistic way of thinking.[web 3]

- Monism, the nonplurality of the world. Although the phenomenal world appears as a plurality of "things", in reality they are "of a single cloth".[web 3]

- Advaita, the nondifference of subject and object, or nonduality between subject and object.[web 3]

- Advaya, the identity of phenomena and the Absolute, the "nonduality of duality and nonduality",[web 3] c.q. the nonduality of relative and ultimate truth as found in Madhyamaka and the two truths doctrine.

- Mysticism, a mystical unity between God and man.[web 3]

The idea of a "nondual consciousness" has gained attraction and popularity in western spirituality and New Age-thinking. It is recognized in the Asian traditions, but also in western and Mediterranean religious traditions, and in western philosophy.[22] Nondual consciousness is perceived in a wide variety of religious traditions:

- Hinduism:

- Buddhism:

- Sikhism[34]

- Taoism[35]

- Subud[22]

- Abrahamic traditions:

- Sufism[35]

- Western philosophy:

- Neo-platonism[citation needed]

Hinduism

"Advaita" refers to nondualism, non-distinction between realities, the oneness of Atman and Brahman, as in Vedanta, Shaktism and Shaivism.[36] Although the term is best known from the Advaita Vedanta school of Adi Shankara, "advaita" is used in treatises by numerous medieval era Indian scholars, as well as modern schools and teachers.[note 4]The Hindu concept of Advaita refers to the idea that all of the universe is one essential reality, and that all facets and aspects of the universe is ultimately an expression or appearance of that one reality.[36] According to Dasgupta and Mohanta, non-dualism developed in various strands of Indian thought, both Vedic and Buddhist, from the Upanishadic period onward.[3] The oldest traces of nondualism in Indian thought may be found in the Chandogya Upanishad, which pre-dates the earliest Buddhism. Pre-sectarian Buddhism may also have been responding to the teachings of the Chandogya Upanishad, rejecting some of its Atman-Brahman related metaphysics.[37][note 5]

Advaita appears in different shades in various schools of Hinduism such as in Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita Vedanta (Vaishnavism), Suddhadvaita Vedanta (Vaishnavism), Shaivism and Shaktism.[36][40][41] It implies, in Advaita Vedanta of Adi Shankara, that all of the reality is Brahman,[36] and that the Atman (soul, self) and Brahman (ultimate unchanging reality) are one.[42][43] Advaita ideas of schools within Hinduism contrasts with its Dvaita schools such as of Madhvacharya who stated that the experienced reality and God are two (dual) and distinct.[44][45]

Vedanta

Several schools of Vedanta teach a form of nondualism. The best-known is Advaita Vedanta, but other nondual Vedanta schools also have a significant influence and following, such as Vishishtadvaita Vedanta and Shuddhadvaita,[36] both of which are bhedabheda.Advaita Vedanta

Swans are important figures in Advaita

The nonduality of the Advaita Vedantins is of the identity of Brahman and the Atman.[46] Advaita has become a broad current in Indian culture and religions, influencing subsequent traditions like Kashmir Shaivism.

The oldest surviving manuscript on Advaita Vedanta is by Gauḍapāda (6th century CE),[4] who has traditionally been regarded as the teacher of Govinda bhagavatpāda and the grandteacher of Shankara. Advaita is best known from the Advaita Vedanta tradition of Adi Shankara, who states that Brahman is pure Being, Consciousness and Bliss (Sat-cit-ananda).[47]

Advaita, states Murti, is the knowledge of Brahman and self-consciousness (Vijnana) without differences.[48] The goal of Vedanta is to know the "truly real" and thus become one with it.[49] According to Advaita Vedanta, Brahman is the highest Reality,[50][51][52] The universe, according to Advaita philosophy, does not simply come from Brahman, it is Brahman. Brahman is the single binding unity behind the diversity in all that exists in the universe.[51] Brahman is also that which is the cause of all changes.[51][53][54] Brahman is the "creative principle which lies realized in the whole world".[55]

The nondualism of Advaita, relies on the Hindu concept of Ātman which is a Sanskrit word that means "real self" of the individual,[56][57] "essence",[web 5] and soul.[56][58] Ātman is the first principle,[59] the true self of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual. Atman is the Universal Principle, one eternal undifferentiated self-luminous consciousness, asserts Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism.[60][61]

Advaita Vedanta philosophy considers Atman as self-existent awareness, limitless, non-dual and same as Brahman.[62] Advaita school asserts that there is "soul, self" within each living entity which is fully identical with Brahman.[63][64] This identity holds that there is One Soul that connects and exists in all living beings, regardless of their shapes or forms, there is no distinction, no superior, no inferior, no separate devotee soul (Atman), no separate God soul (Brahman).[63] The Oneness unifies all beings, there is the divine in every being, and all existence is a single Reality, state the Advaita Vedantins.[65] The nondualism concept of Advaita Vedanta asserts that each soul is non-different from the infinite Brahman.[66]

Advaita Vedanta – Three levels of reality

Advaita Vedanta adopts sublation as the criterion to postulate three levels of ontological reality:[67][68]- Pāramārthika (paramartha, absolute), the Reality that is metaphysically true and ontologically accurate. It is the state of experiencing that "which is absolutely real and into which both other reality levels can be resolved". This experience can't be sublated (exceeded) by any other experience.[67][68]

- Vyāvahārika (vyavahara), or samvriti-saya,[69] consisting of the empirical or pragmatic reality. It is ever-changing over time, thus empirically true at a given time and context but not metaphysically true. It is "our world of experience, the phenomenal world that we handle every day when we are awake". It is the level in which both jiva (living creatures or individual souls) and Iswara are true; here, the material world is also true.[68]

- Prāthibhāsika (pratibhasika, apparent reality, unreality), "reality based on imagination alone". It is the level of experience in which the mind constructs its own reality. A well-known example is the perception of a rope in the dark as being a snake.[68]

Similarities and differences with Buddhism

Scholars state that Advaita Vedanta was influenced by Mahayana Buddhism, given the common terminology and methodology and some common doctrines.[70][71] Eliot Deutsch and Rohit Dalvi state:In any event a close relationship between the Mahayana schools and Vedanta did exist, with the latter borrowing some of the dialectical techniques, if not the specific doctrines, of the former.[72]Advaita Vedanta is related to Madhyamaka via Gaudapada, who took over the Buddhist doctrine that ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra).[4] Shankara harmonised Gaudapada's ideas with the Upanishadic texts, and provided an orthodox hermeneutical basis for heterodox Buddhist phenomology.[73][74]

Gaudapada adopted the Buddhist concept of ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra).[4] The Buddhist term is often used interchangeably with the term citta-mātra, but they have different meanings. The standard translation of both terms is "consciousness-only" or "mind-only." Advaita Vedanta has been called "idealistic monism" by scholars, but some disagree with this label.[75][76] Another concept found in both Madhyamaka Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta is Ajativada ("ajāta"), which Gaudapada adopted from Nagarjuna's philosophy.[77][78][note 6] Gaudapada "wove [both doctrines] into a philosophy of the Mandukaya Upanisad, which was further developed by Shankara.[80][note 7]

Michael Comans states there is a fundamental difference between Buddhist thought and that of Gaudapada, in that Buddhism has as its philosophical basis the doctrine of Dependent Origination according to which "everything is without an essential nature (nissvabhava), and everything is empty of essential nature (svabhava-sunya)", while Gaudapada does not rely on this principle at all. Gaudapada's Ajativada is an outcome of reasoning applied to an unchanging nondual reality according to which "there exists a Reality (sat) that is unborn (aja)" that has essential nature (svabhava), and this is the "eternal, fearless, undecaying Self (Atman) and Brahman".[82] Thus, Gaudapada differs from Buddhist scholars such as Nagarjuna, states Comans, by accepting the premises and relying on the fundamental teaching of the Upanishads.[82] Among other things, Vedanta school of Hinduism holds the premise, "Atman exists, as self evident truth", a concept it uses in its theory of nondualism. Buddhism, in contrast, holds the premise, "Atman does not exist (or, An-atman) as self evident".[83][84][85]

Mahadevan suggests that Gaudapada adopted Buddhist terminology and adapted its doctrines to his Vedantic goals, much like early Buddhism adopted Upanishadic terminology and adapted its doctrines to Buddhist goals; both used pre-existing concepts and ideas to convey new meanings.[86] Dasgupta and Mohanta note that Buddhism and Shankara's Advaita Vedanta are not opposing systems, but "different phases of development of the same non-dualistic metaphysics from the Upanishadic period to the time of Sankara."[3]

Vishishtadvaita Vedanta

Ramanuja, founder of Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, taught 'qualified nondualism' doctrine.

Vishishtadvaita Vedanta is another main school of Vedanta and teaches the nonduality of the qualified whole, in which Brahman alone exists, but is characterized by multiplicity. It can be described as "qualified monism," or "qualified non-dualism," or "attributive monism."

According to this school, the world is real, yet underlying all the differences is an all-embracing unity, of which all "things" are an "attribute." Ramanuja, the main proponent of Vishishtadvaita philosophy contends that the Prasthana Traya ("The three courses") – namely the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras – are to be interpreted in a way that shows this unity in diversity, for any other way would violate their consistency.

Vedanta Desika defines Vishishtadvaita using the statement: Asesha Chit-Achit Prakaaram Brahmaikameva Tatvam – "Brahman, as qualified by the sentient and insentient modes (or attributes), is the only reality."

Neo-Vedanta

Neo-Vedanta, also called "neo-Hinduism"[87] is a modern interpretation of Hinduism which developed in response to western colonialism and orientalism, and aims to present Hinduism as a "homogenized ideal of Hinduism"[88] with Advaita Vedanta as its central doctrine.[89]Neo-Vedanta, as represented by Vivekananda and Radhakrishnan, is indebted to Advaita vedanta, but also reflects Advaya-philosophy. A main influence on neo-Advaita was Ramakrishna, himself a bhakta and tantrika, and the guru of Vivekananda. According to Michael Taft, Ramakrishna reconciled the dualism of formlessness and form.[90] Ramakrishna regarded the Supreme Being to be both Personal and Impersonal, active and inactive:

When I think of the Supreme Being as inactive – neither creating nor preserving nor destroying – I call Him Brahman or Purusha, the Impersonal God. When I think of Him as active – creating, preserving and destroying – I call Him Sakti or Maya or Prakriti, the Personal God. But the distinction between them does not mean a difference. The Personal and Impersonal are the same thing, like milk and its whiteness, the diamond and its lustre, the snake and its wriggling motion. It is impossible to conceive of the one without the other. The Divine Mother and Brahman are one.[91]Radhakrishnan acknowledged the reality and diversity of the world of experience, which he saw as grounded in and supported by the absolute or Brahman.[web 6][note 8] According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda's neo-Advaita "reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism":[93]

The Neo-Vedanta is also Advaitic inasmuch as it holds that Brahman, the Ultimate Reality, is one without a second, ekamevadvitiyam. But as distinguished from the traditional Advaita of Sankara, it is a synthetic Vedanta which reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism and also other theories of reality. In this sense it may also be called concrete monism in so far as it holds that Brahman is both qualified, saguna, and qualityless, nirguna.[93]Radhakrishnan also reinterpreted Shankara's notion of maya. According to Radhakrishnan, maya is not a strict absolute idealism, but "a subjective misperception of the world as ultimately real."[web 6] According to Sarma, standing in the tradition of Nisargadatta Maharaj, Advaitavāda means "spiritual non-dualism or absolutism",[94] in which opposites are manifestations of the Absolute, which itself is immanent and transcendent:[95]

All opposites like being and non-being, life and death, good and evil, light and darkness, gods and men, soul and nature are viewed as manifestations of the Absolute which is immanent in the universe and yet transcends it.[96]

Kashmir Shaivism

Advaita is also a central concept in various schools of Shaivism, such as Kashmir Shaivism[36] and Shiva Advaita.Kashmir Shaivism is a school of Śaivism, described by Abhinavagupta[note 9] as "paradvaita", meaning "the supreme and absolute non-dualism".[web 7] It is categorized by various scholars as monistic[97] idealism (absolute idealism, theistic monism,[98] realistic idealism,[99] transcendental physicalism or concrete monism[99]).

Kashmir Saivism is based on a strong monistic interpretation of the Bhairava Tantras and its subcategory the Kaula Tantras, which were tantras written by the Kapalikas.[100] There was additionally a revelation of the Siva Sutras to Vasugupta.[100] Kashmir Saivism claimed to supersede the dualistic Shaiva Siddhanta.[101] Somananda, the first theologian of monistic Saivism, was the teacher of Utpaladeva, who was the grand-teacher of Abhinavagupta, who in turn was the teacher of Ksemaraja.[100][102]

The philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism can be seen in contrast to Shankara's Advaita.[103] Advaita Vedanta holds that Brahman is inactive (niṣkriya) and the phenomenal world is an illusion (māyā). In Kashmir Shavisim, all things are a manifestation of the Universal Consciousness, Chit or Brahman.[104][105] Kashmir Shavisim sees the phenomenal world (Śakti) as real: it exists, and has its being in Consciousness (Chit).[106]

Kashmir Shaivism was influenced by, and took over doctrines from, several orthodox and heterodox Indian religious and philosophical traditions.[107] These include Vedanta, Samkhya, Patanjali Yoga and Nyayas, and various Buddhist schools, including Yogacara and Madhyamika,[107] but also Tantra and the Nath-tradition.[108]

Contemporary vernacular Advaita

Advaita is also part of other Indian traditions, which are less strongly, or not all, organised in monastic and institutional organisations. Although often called "Advaita Vedanta," these traditions have their origins in vernacular movements and "householder" traditions, and have close ties to the Nath, Nayanars and Sant Mat traditions.Ramana Maharshi

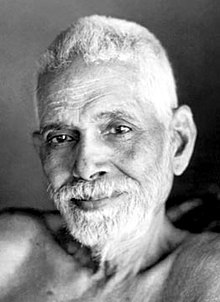

Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950) explained his insight using Shaiva Siddhanta, Advaita Vedanta and Yoga teachings.

Ramana Maharshi (30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950) is widely acknowledged as one of the outstanding Indian gurus of modern times.[109] Ramana's teachings are often interpreted as Advaita Vedanta, though Ramana Maharshi never "received diksha (initiation) from any recognised authority".[web 8] Ramana himself did not call his insights advaita:

D. Does Sri Bhagavan advocate advaita?

M. Dvaita and advaita are relative terms. They are based on the sense of duality. The Self is as it is. There is neither dvaita nor advaita. "I Am that I Am."[note 10] Simple Being is the Self.[111]

Neo-Advaita

Neo-Advaita is a New Religious Movement based on a modern, western interpretation of Advaita Vedanta, especially the teachings of Ramana Maharshi.[112] According to Arthur Versluis, neo-Advaita is part of a larger religious current which he calls immediatism,[113][web 11] "the assertion of immediate spiritual illumination without much if any preparatory practice within a particular religious tradition."[web 11] Neo-Advaita is criticized for this immediatism and its lack of preparatory practices.[114][note 11][116][note 12] Notable neo-advaita teachers are H. W. L. Poonja[117][112] and his students Gangaji,[118] Andrew Cohen,[note 13], and Eckhart Tolle.[112]Natha Sampradaya and Inchegeri Sampradaya

The Natha Sampradaya, with Nath yogis such as Gorakhnath, introduced Sahaja, the concept of a spontaneous spirituality. Sahaja means "spontaneous, natural, simple, or easy".[web 15] According to Ken Wilber, this state reflects nonduality.[120]Buddhism

The Advaya concept of nonduality refers to the "non-two" understanding of reality, which has its origins in Madhyamaka-thought, which in turn is built on earlier Buddhist thought, and expressed in the two truths doctrine. In Nagarjuna's interpretation it is the non-duality of conventional and ultimate truth, or the overcoming of dichotomies such as that between samsara (conditioned or relative reality, rebirth) and nirvana (unconditioned and absolute reality, liberation).[121][122]Nondualism in Buddhism is explicitly represented by the concept of Buddha-nature, and Tibetan concepts like rigpa and shentong. It has its roots in Buddhist ideas of luminous mind, the "pure" consciousness which shines through when purified from the defilements of hatred, anger and ignorance. Nondualism can also be found in Yogacara thought, and its concept of the alaija-vijnana. Subsequently, combinations of Buddha-nature thought and Yogacara, and also of Yogacara and Madhyamaka, developed in India, Tibet and China, and can be found in Tibetan Buddhism and Zen.

The nonduality of relative and ultimate truth was further developed and re-interpreted in Chinese Buddhism, where the two truths doctrine came to refer to the nonduality of nirvana and samsara, re-incorporating essentialist notions.

Indian Buddhism

Madhyamaka – nonduality of conventional and ultimate truth

In Madhyamaka Buddhism Advaya refers to the nonduality of conventional and ultimate truth,[123] or the relative (phenomenal) world and the Absolute, such as in samsara and nirvana.[36] Madhyamaka, also known as Śūnyavāda, refers primarily to a Mahāyāna Buddhist school of philosophy[124] founded by Nāgārjuna.

In Madhyamaka, the two truths refer to conventional and ultimate truth.[125] The ultimate truth is "emptiness", or non-existence of inherently existing "things",[126] and the "emptiness of emptiness": emptiness does not in itself constitute an absolute reality. Conventionally, "things" exist, but ultimately, they are "empty" of any existence on their own, as described in Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā:

The Buddha's teaching of the Dharma is based on two truths: a truth of worldly convention and an ultimate truth. Those who do not understand the distinction drawn between these two truths do not understand the Buddha's profound truth. Without a foundation in the conventional truth the significance of the ultimate cannot be taught. Without understanding the significance of the ultimate, liberation is not achieved.[note 14]"Emptiness" is a consequence of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent arising),[127] the teaching that no dharma ("thing") has an existence of its own, but always comes into existence in dependence on other dharmas. According to Madhyamaka all phenomena are empty of "substance" or "essence" (Sanskrit: svabhāva) because they are dependently co-arisen. Likewise it is because they are dependently co-arisen that they have no intrinsic, independent reality of their own. Madhyamaka also rejects the existence of an absolute reality or Self.[128] Ultimately, "absolute reality" is not an absolute, or the non-duality of a personal self and an absolute Self, but the deconstruction of such reifications.

It also means that there is no "transcendental ground," and that "ultimate reality" has no existence of its own, but is the negation of such a transcendental reality, and the impossibility of any statement on such an ultimately existing transcendental reality: it is no more than a fabrication of the mind.[web 16][note 15] Susan Kahn further explains:

Ultimate truth does not point to a transcendent reality, but to the transcendence of deception. It is critical to emphasize that the ultimate truth of emptiness is a negational truth. In looking for inherently existent phenomena it is revealed that it cannot be found. This absence is not findable because it is not an entity, just as a room without an elephant in it does not contain an elephantless substance. Even conventionally, elephantlessness does not exist. Ultimate truth or emptiness does not point to an essence or nature, however subtle, that everything is made of.[web 17]In Madhyamaka-Buddhism, "Advaya" is an epistemological approach.[48] It is the recognition that ultimately everything is impermanent (anicca) and devoid of "self" or "essence" (anatta),[129][130][131] and that this emptiness does not constitute an "absolute" reality in itself.[note 16].

The later Madhyamikas, states Yuichi Kajiyama, developed the Advaya definition as a means to Nirvikalpa-Samadhi by suggesting that "things arise neither from their own selves nor from other things, and that when subject and object are unreal, the mind, being not different, cannot be true either; thereby one must abandon attachment to cognition of nonduality as well, and understand the lack of intrinsic nature of everything". Thus, the Buddhist nondualism or Advaya concept became a means to realizing absolute emptiness.[132]

Yogacara

In Yogacara, adhyava may also refer to overcoming the dichotomies of cognitum and cognition imposed by conceptual thought.[36] Yogācāra (Sanskrit; literally: "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga")[133] is an influential school of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing phenomenology and (some argue)[clarification needed] ontology[134] through the interior lens of meditative and yogic practices. It developed within Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism in about the 4th century CE.[135]The concept of adyava in Yogacara is an epistemological stance on the nature of knowledge. Early Buddhism schools such as Sarvastivada and Sautrāntika, that thrived through the early centuries of the common era, postulated a dualism, dvaya, wherein grasping (grahaka, "cognition") and the grasped (gradya, "cognitum")[136] both are really existing.[132][136][137] Yogacara postulates an advaya of grasping and the grasped, stating that only the mind[132] (citta-mātra) or the representations we cognize (vijñapti-mātra),[138][note 17] really exist.[132][136][138]

In Yogacara-thought, cognition is a modification of the base-consciousness, alaya-vijnana. By the reification of these modifications into separate consciousnesses, the Eighth Consciousnesses of Yogacara came into existence.[139] In later Buddhist thought, which took an idealistic turn, the storehouse-consciousness or base-consciousness came to be seen as a pure consciousness, from which everything arises. According to the Lankavatara Sutra and the schools of Chan/Zen Buddhism, the alaya-vijnana is identical with the tathagata-garbha[note 18], and is fundamentally pure.[140] Vijñapti-mātra, coupled with Buddha-nature or tathagatagarba, has been an influential concept in the subsequent development of Mahayana Buddhism, not only in India, but also in China and Tibet, most notable in the Chán (Zen) and Dzogchen traditions.

According to Kochumuttom, Yogacara is a realistic pluralism. It does not deny the existence of individual beings, but denies the following:[76]

1. That the absolute mode of reality is consciousness/mind/ideas,Vijñapti-mātra, "consciousness-only" or "representation-only" is one of the main features of Yogācāra philosophy. It is often used interchangeably with the term citta-mātra, but they have different meanings. The standard translation of both terms is "consciousness-only" or "mind-only." Several modern researchers object to this translation, and the accompanying label of "absolute idealism" or "idealistic monism".[76] A better translation for vijñapti-mātra is representation-only.[138]

2. That the individual beings are transformations or evolutes of an absolute consciousness/mind/idea,

3. That the individual beings are but illusory appearances of a monistic reality.[141]

Vijñapti-mātra then means "mere representation of consciousness":

[T]he phrase vijñaptimātratā-vāda means a theory which says that the world as it appears to the unenlightened ones is mere representation of consciousness. Therefore, any attempt to interpret vijñaptimātratā-vāda as idealism would be a gross misunderstanding of it.[138]The term vijñapti-mātra replaced the "more metaphysical"[142] term citta-mātra used in the Lankavatara Sutra.[143] The Lankavatara Sutra "appears to be one of the earliest attempts to provide a philosophical justification for the Absolutism that emerged in Mahayana in relation to the concept of Buddha".[144] It uses the term citta-mātra, which means properly "thought-only". By using this term it develops an ontology, in contrast to the epistemology of the term vijñapti-mātra. The Lankavatara Sutra equates citta and the absolute. According to Kochumuttom, this is not the way Yogacara uses the term vijñapti:[145]

[T]he absolute state is defined simply as emptiness, namely the emptiness of subject–object distinction. Once thus defined as emptiness (sunyata), it receives a number of synonyms, none of which betray idealism.[146]The Yogācārins defined three basic modes by which we perceive our world. These are referred to in Yogācāra as the three natures of perception. They are:

- Parikalpita (literally, "fully conceptualized"): "imaginary nature", wherein things are incorrectly comprehended based on conceptual construction, through attachment and erroneous discrimination.

- Paratantra (literally, "other dependent"): "dependent nature", by which the correct understanding of the dependently originated nature of things is understood.

- Pariniṣpanna (literally, "fully accomplished"): "absolute nature", through which one comprehends things as they are in themselves, uninfluenced by any conceptualization at all.

Buddha-nature

Vijñapti-mātra and the two truths doctrine, as understood in Chinese Buddhism, are closely linked to Buddha-nature. Those teachings have had a profound influence on Mahayana Buddhism, not only in India, but also in China and Tibet, most notably the Chán (Zen) and Dzogchen traditions. They may be related to an archaic form of Buddhism which is close to Brahmanical beliefs, elements of which are preserved in the Nikayas,[147][148][149][150] and survived in the Mahayana tradition.[151][152] Contrary to popular opinion, the Theravada and Mahayana traditions may be "divergent, but equally reliable records of a pre-canonical Buddhism which is now lost forever."[151] The Mahayana tradition may have preserved a very old, "pre-Canonical" tradition, which was largely, but not completely, left out of the Theravada-canon.[152]The Buddhist teachings on the Buddha-nature may be regarded as a form of nondualism.[153] Buddha-nature is the essential element that allows sentient beings to become Buddhas.[154] The term, Buddha nature, is a translation of the Sanskrit coinage, 'Buddha-dhātu', which seems first to have appeared in the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra,[155] where it refers to 'a sacred nature that is the basis for [beings'] becoming buddhas.'[156] The term seems to have been used most frequently to translate the Sanskrit "Tathāgatagarbha". The Sanskrit term "tathāgatagarbha" may be parsed into tathāgata ("the one thus gone", referring to the Buddha) and garbha ("womb").[note 19] The tathagatagarbha, when freed from avidya ("ignorance"), is the dharmakaya, the Absolute.

Tantric Buddhism

Tantra is a religious tradition that originated in India in the middle of the first millennium CE, and has been practiced by Buddhists, Hindus and Jains throughout south and southeast Asia.[157] It views humans as a microcosmos which mirrors the macrocosmos.[158] Its aim is to gain access to the energy or enlightened consciousness of the godhead or absolute, by embodying this energy or consciousness through rituals.[158] It views the godhead as both transcendent and immanent, and views the world as real, and not as an illusion:[159]Rather than attempting to see through or transcend the world, the practitioner comes to recognize "that" (the world) as "I" (the supreme egoity of the godhead): in other words, s/he gains a "god's eye view" of the universe, and recognizes it to be nothing other than herself/himself. For East Asian Buddhist Tantra in particular, this means that the totality of the cosmos is a "realm of Dharma", sharing an underlying common principle.[160]Ramakrishna too was a tantric adherent, although his tantric background was overlaid and smoothed with an Advaita interpretation by his student Vivekananda.[161]

East-Asian Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism – nonduality of mundane and highest reality

In Chinese Buddhism the Two truths doctrine was interpreted as an ontological teaching of three truths,[162] states Whalen Lai, wherein "samsaric being and nirvanic emptiness as well any and all distinctions are not two".[163] The Chinese Buddhist scholars posited that there is a third truth above the mundane truth of samsaric being and the highest truth nirvanic emptiness (sunyata).[164][162] In one description, everything is posited to be simultaneously "empty, real and neither".[163] According to Lai, most scholars of Chinese Buddhism, unlike Nagarjuna, failed to realize that the two truths were epistemic, not ontological.[164] This mistake was identified and discussed by Jizang of Sanlun school.[164]Chinese Buddhism evolved over time.[165] Before 400 CE, states Lai, the Chinese understood the Buddhist doctrine to be that "karmic rebirth entailed the transmigration of soul".[165] It was monk Mindu who understood that the Buddha taught a no soul doctrine, and he tried to explain this to his Buddhist sangha, but was vilified for denying the existence of soul.[165] Mindu's ideas, however, began a momentum that led to the emergence of six prajna schools in the 4th and 5th century CE.[165] In the 6th century CE it became clear that anatman and sunyata are central Buddhist teachings, which make the postulation of an eternal self problematic.[166][167]

Another point of confusion was the Two truths doctrine of Madhyamaka, the mundane truth and the highest truth. Chinese thinking took this to refer to two ontological truths: reality exists at two levels, the mundane level of samsara and the highest level of nirvana emptiness. But in Madhyamaka these are two epistemological truths, two different ways to look at reality. The early Chinese scholars supposed that there is an essential truth above the two truths, which unites both these.[164][167] This three truths doctrine was different from a similarly named doctrine of Yogacara and Indian Buddhism.[167]

Hua-yen Buddhism

The Huayan school or Flower Garland is a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy that flourished in China during the Tang period particularly with Fazang (~700 CE). It is based on the Sanskrit Flower Garland Sutra (S. Avataṃsaka Sūtra, C. Huayan Jing) and on a lengthy Chinese interpretation of it, the Huayan Lun. The name Flower Garland is meant to suggest the crowning glory of profound understanding. Huayan teaches the Four Dharmadhatu, four ways to view reality:- All dharmas are seen as particular separate events;

- All events are an expression of the absolute;

- Events and essence interpenetrate;

- All events interpenetrate.[168]

Zen Buddhism

The Buddha-nature and Yogacara philosophies have had a strong influence on Chán and Zen. The teachings of Zen are expressed by a set of polarities: Buddha-nature – sunyata;[169][170] absolute-relative;[171] sudden and gradual enlightenment.[172]

The Lankavatara-sutra, a popular sutra in Zen, endorses the Buddha-nature and emphasizes purity of mind, which can be attained in gradations. The Diamond-sutra, another popular sutra, emphasizes sunyata, which "must be realized totally or not at all".[173] The Prajnaparamita Sutras emphasize the non-duality of form and emptiness: form is emptiness, emptiness is form, as the Heart Sutra says.[171] According to Chinul, Zen points not to mere emptiness, but to suchness or the dharmadhatu.[174]

The idea that the ultimate reality is present in the daily world of relative reality fitted into the Chinese culture which emphasized the mundane world and society. But this does not explain how the absolute is present in the relative world. This question is answered in such schemata as the Five Ranks of Tozan[175] and the Oxherding Pictures.

The continuous pondering of the break-through kōan (shokan[176]) or Hua Tou, "word head",[177] leads to kensho, an initial insight into "seeing the (Buddha-)nature.[178] According to Hori, a central theme of many koans is the "identity of opposites", and point to the original nonduality.[179][180] Victor Sogen Hori describes kensho, when attained through koan-study, as the absence of subject–object duality.[181] The aim of the so-called break-through koan is to see the "nonduality of subject and object", [179][180] in which "subject and object are no longer separate and distinct."[182]

Zen Buddhist training does not end with kenshō. Practice is to be continued to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life,[183][184][185][186] to fully manifest the nonduality of absolute and relative.[187][188] To deepen the initial insight of kensho, shikantaza and kōan-study are necessary. This trajectory of initial insight followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji Yixuan in his Three Mysterious Gates, the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin,[189] the Five Ranks, and the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures[190] which detail the steps on the Path.

Essence-function in Korean Buddhism

The polarity of absolute and relative is also expressed as "essence-function". The absolute is essence, the relative is function. They can't be seen as separate realities, but interpenetrate each other. The distinction does not "exclude any other frameworks such as neng-so or 'subject-object' constructions", though the two "are completely different from each other in terms of their way of thinking".[191] In Korean Buddhism, essence-function is also expressed as "body" and "the body's functions".[192] A metaphor for essence-function is "a lamp and its light", a phrase from the Platform Sutra, where Essence is lamp and Function is light.[193]Tibetan Buddhism

Adyava: Gelugpa Prasangika-Madhyamaka

The Gelugpa school, following Tsongkhapa, adheres to the adyava Prasaṅgika Mādhyamaka view, which states that all phenomena are sunyata, empty of self-nature, and that this "emptiness" is itself only a qualification, not a concretely existing "absolute" reality.[194]This view is reiterated by some western Madhyamaka-inspired writers,[web 19][web 20][web 21] stressing that there is no transcendental reality beyond this phenomenal world.[web 22][note 20]

Buddha-nature and the nature of mind

Shentong

In Tibetan Buddhism, the essentialist position is represented by shentong, while the nominalist, or non-essentialist position, is represented by rangtong.Shentong is a philosophical sub-school found in Tibetan Buddhism. Its adherents generally hold that the nature of mind, the substratum of the mindstream, is "empty" (Wylie: stong) of "other" (Wylie: gzhan), i.e., empty of all qualities other than an inherently existing, ineffable nature. Shentong has often been incorrectly associated with the Cittamātra (Yogacara) position, but is in fact also Madhyamaka,[195] and is present primarily as the main philosophical theory of the Jonang school, although it is also taught by the Sakya[196] and Kagyu schools.[197][198] According to Shentongpa (proponents of shentong), the emptiness of ultimate reality should not be characterized in the same way as the emptiness of apparent phenomena because it is prabhāśvara-saṃtāna, or "luminous mindstream" endowed with limitless Buddha qualities.[199] It is empty of all that is false, not empty of the limitless Buddha qualities that are its innate nature.

The contrasting Prasaṅgika view that all phenomena are sunyata, empty of self-nature, and that this "emptiness" is not a concretely existing "absolute" reality, is labeled rangtong, "empty of other."[194]

The shentong-view is related to the Ratnagotravibhāga sutra and the Yogacara-Madhyamaka synthesis of Śāntarakṣita. The truth of sunyata is acknowledged, but not considered to be the highest truth, which is the empty nature of mind. Insight into sunyata is preparatory for the recognition of the nature of mind.

Dzogchen

Dzogchen is concerned with the "natural state" and emphasizes direct experience. The state of nondual awareness is called rigpa.[citation needed] This primordial nature is clear light, unproduced and unchanging, free from all defilements. Through meditation, the Dzogchen practitioner experiences that thoughts have no substance. Mental phenomena arise and fall in the mind, but fundamentally they are empty. The practitioner then considers where the mind itself resides. Through careful examination one realizes that the mind is emptiness.[200]Karma Lingpa (1326–1386) revealed "Self-Liberation through seeing with naked awareness" (rigpa ngo-sprod,[note 21]) which is attributed to Padmasambhava.[201][note 22] The text gives an introduction, or pointing-out instruction (ngo-spro), into rigpa, the state of presence and awareness.[201] In this text, Karma Lingpa writes the following regarding the unity of various terms for nonduality:

With respect to its having a name, the various names that are applied to it are inconceivable (in their numbers).

Some call it "the nature of the mind"[note 23] or "mind itself."

Some Tirthikas call it by the name Atman or "the Self."

The Sravakas call it the doctrine of Anatman or "the absence of a self."

The Chittamatrins call it by the name Chitta or "the Mind."

Some call it the Prajnaparamita or "the Perfection of Wisdom."

Some call it the name Tathagata-garbha or "the embryo of Buddhahood."

Some call it by the name Mahamudra or "the Great Symbol."

Some call it by the name "the Unique Sphere."[note 24]

Some call it by the name Dharmadhatu or "the dimension of Reality."

Some call it by the name Alaya or "the basis of everything."

And some simply call it by the name "ordinary awareness."[206][note 25]

Other eastern religions

Apart from Hinduism and Buddhism, self-proclaimed nondualists have also discerned nondualism in other religious traditions.Sikhism

Sikh theology suggests human souls and the monotheistic God are two different realities (dualism),[207] distinguishing it from the monistic and various shades of nondualistic philosophies of other Indian religions.[208] However, Sikh scholars have attempted to explore nondualism exegesis of Sikh scriptures, such as during the neocolonial reformist movement by Bhai Vir Singh of the Singh Sabha. According to Mandair, Singh interprets the Sikh scriptures as teaching nonduality.[209]Taoism

Taoism's wu wei (Chinese wu, not; wei, doing) is a term with various translations[note 26] and interpretations designed to distinguish it from passivity. The concept of Yin and Yang, often mistakenly conceived of as a symbol of dualism, is actually meant to convey the notion that all apparent opposites are complementary parts of a non-dual whole.[210]

Western traditions

A modern strand of thought sees "nondual consciousness" as a universal psychological state, which is a common stratum and of the same essence in different spiritual traditions.[2] It is derived from Neo-Vedanta and neo-Advaita, but has historical roots in neo-Platonism, Western esotericism, and Perennialism. The idea of nondual consciousness as "the central essence"[211] is a universalistic and perennialist idea, which is part of a modern mutual exchange and synthesis of ideas between western spiritual and esoteric traditions and Asian religious revival and reform movements.[note 27]Central elements in the western traditions are Neo-Platonism, which had a strong influence on Christian contemplation c.q. mysticism, and it's accompanying apophatic theology; and Western esotericism, which also incorporated Neo-Platonism and Gnostic elements including Hermeticism. Western traditions are, among others, the idea of a Perennial Philosophy, Swedenborgianism, Unitarianism, Orientalism, Transcendentalism, Theosophy, and New Age.[213]

Eastern movements are the Hindu reform movements such as Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta and Aurobindo's Integral Yoga, the Vipassana movement, and Buddhist modernism.[note 28]

Roman world

Gnosticism

Since its beginning, Gnosticism has been characterized by many dualisms and dualities, including the doctrine of a separate God and Manichaean (good/evil) dualism.[214] Ronald Miller interprets the Gospel of Thomas as a teaching of "nondualistic consciousness".[215]Neoplatonism

The precepts of Neoplatonism of Plotinus (2nd century) assert nondualism.[216] Neoplatonism had a strong influence on Christian mysticism.Some scholars suggest a possible link of more ancient Indian philosophies on Neoplatonism, while other scholars consider these claims as unjustified and extravagant with the counter hypothesis that nondualism developed independently in ancient India and Greece.[217] The nondualism of Advaita Vedanta and Neoplatonism have been compared by various scholars,[218] such as J. F. Staal,[219] Frederick Copleston,[220] Aldo Magris and Mario Piantelli,[221] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,[222] Gwen Griffith-Dickson,[223] John Y. Fenton[224] and Dale Riepe.[225]

Medieval Abrahamic religions

Christian contemplation and mysticism

The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine, St John the Baptist, St Antony Abbot

In Christian mysticism, contemplative prayer and Apophatic theology are central elements. In contemplative prayer, the mind is focused by constant repetition a phrase or word. Saint John Cassian recommended use of the phrase "O God, make speed to save me: O Lord, make haste to help me".[226][227] Another formula for repetition is the name of Jesus.[228][229] or the Jesus Prayer, which has been called "the mantra of the Orthodox Church",[227] although the term "Jesus Prayer" is not found in the Fathers of the Church.[230] The author of The Cloud of Unknowing recommended use of a monosyllabic word, such as "God" or "Love".[231]

Apophatic theology is derived from Neo-Platonism via Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. In this approach, the notion of God is stripped from all positive qualifications, leaving a "darkness" or "unground." It had a strong influence on western mysticism. A notable example is Meister Eckhart, who also attracted attention from Zen-Buddhists like D.T. Suzuki in modern times, due to the similarities between Buddhist thought and Neo-Platonism.

The Cloud of Unknowing – an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century – advocates a mystic relationship with God. The text describes a spiritual union with God through the heart. The author of the text advocates centering prayer, a form of inner silence. According to the text, God can not be known through knowledge or from intellection. It is only by emptying the mind of all created images and thoughts that we can arrive to experience God. Continuing on this line of thought, God is completely unknowable by the mind. God is not known through the intellect but through intense contemplation, motivated by love, and stripped of all thought.[232]

Thomism, though not non-dual in the ordinary sense, considers the unity of God so absolute that even the duality of subject and predicate, to describe him, can be true only by analogy. In Thomist thought, even the Tetragrammaton is only an approximate name, since "I am" involves a predicate whose own essence is its subject.[233]

The former nun and contemplative Bernadette Roberts is considered a nondualist by Jerry Katz.[2]

Jewish Hasidism and Kabbalism

According to Jay Michaelson, nonduality begins to appear in the medieval Jewish textual tradition which peaked in Hasidism.[216] According to Michaelson:Judaism has within it a strong and very ancient mystical tradition that is deeply nondualistic. "Ein Sof" or infinite nothingness is considered the ground face of all that is. God is considered beyond all proposition or preconception. The physical world is seen as emanating from the nothingness as the many faces "partsufim" of god that are all a part of the sacred nothingness.[234]One of the most striking contributions of the Kabbalah, which became a central idea in Chasidic thought, was a highly innovative reading of the monotheistic idea. The belief in "one G-d" is no longer perceived as the mere rejection of other deities or intermediaries, but a denial of any existence outside of G-d.[note 29]

Western esotericism

Western esotericism (also called esotericism and esoterism) is a scholarly term for a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements which have developed within Western society. They are largely distinct both from orthodox Judeo-Christian religion and from Enlightenment rationalism. The earliest traditions which later analysis would label as forms of Western esotericism emerged in the Eastern Mediterranean during Late Antiquity, where Hermetism, Gnosticism, and Neoplatonism developed as schools of thought distinct from what became mainstream Christianity. In Renaissance Europe, interest in many of these older ideas increased, with various intellectuals seeking to combine "pagan" philosophies with the Kabbalah and with Christian philosophy, resulting in the emergence of esoteric movements like Christian theosophy.Perennial philosophy

The Perennial philosophy has its roots in the Renaissance interest in neo-Platonism and its idea of The One, from which all existence emanates. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) sought to integrate Hermeticism with Greek and Jewish-Christian thought,[235] discerning a Prisca theologia which could be found in all ages.[236] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–94) suggested that truth could be found in many, rather than just two, traditions. He proposed a harmony between the thought of Plato and Aristotle, and saw aspects of the Prisca theologia in Averroes, the Koran, the Cabala and other sources.[237] Agostino Steuco (1497–1548) coined the term philosophia perennis.[238]Orientalism

The western world has been exposed to Indian religions since the late 18th century.[239] The first western translation of a Sanskrit text was made in 1785.[239] It marked a growing interest in Indian culture and languages.[240] The first translation of the dualism and nondualism discussing Upanishads appeared in two parts in 1801 and 1802[241] and influenced Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them "the consolation of my life".[242] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[243]Transcendentalism and Unitarian Universalism

Transcendentalism was an early 19th-century liberal Protestant movement that developed in the 1830s and 1840s in the Eastern region of the United States. It was rooted in English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume.[web 28]The Transcendentalists emphasised an intuitive, experiential approach of religion.[web 29] Following Schleiermacher,[244] an individual's intuition of truth was taken as the criterion for truth.[web 29] In the late 18th and early 19th century, the first translations of Hindu texts appeared, which were read by the Transcendentalists and influenced their thinking.[web 29] The Transcendentalists also endorsed universalist and Unitarianist ideas, leading to Unitarian Universalism, the idea that there must be truth in other religions as well, since a loving God would redeem all living beings, not just Christians.[web 29][web 30]

Among the transcendentalists' core beliefs was the inherent goodness of both people and nature. Transcendentalists believed that society and its institutions—particularly organized religion and political parties—ultimately corrupted the purity of the individual. They had faith that people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent. It is only from such real individuals that true community could be formed.

The major figures in the movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Margaret Fuller and Amos Bronson Alcott.

Neo-Vedanta

Unitarian Universalism had a strong impact on Ram Mohan Roy and the Brahmo Samaj, and subsequently on Swami Vivekananda. Vivekananda was one of the main representatives of Neo-Vedanta, a modern interpretation of Hinduism in line with western esoteric traditions, especially Transcendentalism, New Thought and Theosophy.[245] His reinterpretation was, and is, very successful, creating a new understanding and appreciation of Hinduism within and outside India,[245] and was the principal reason for the enthusiastic reception of yoga, transcendental meditation and other forms of Indian spiritual self-improvement in the West.[246]Narendranath Datta (Swami Vivekananda) became a member of a Freemasonry lodge "at some point before 1884"[247] and of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj in his twenties, a breakaway faction of the Brahmo Samaj led by Keshab Chandra Sen and Debendranath Tagore.[248] Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, had a strong sympathy for the Unitarians,[249] who were closely connected to the Transcendentalists, who in turn were interested in and influenced by Indian religions early on.[250] It was in this cultic[251] milieu that Narendra became acquainted with Western esotericism.[252] Debendranath Tagore brought this "neo-Hinduism" closer in line with western esotericism, a development which was furthered by Keshubchandra Sen,[253] who was also influenced by transcendentalism, which emphasised personal religious experience over mere reasoning and theology.[254] Sen's influence brought Vivekananda fully into contact with western esotericism, and it was also via Sen that he met Ramakrishna.[255]

Vivekananda's acquaintance with western esotericism made him very successful in western esoteric circles, beginning with his speech in 1893 at the Parliament of Religions. Vivekananda adapted traditional Hindu ideas and religiosity to suit the needs and understandings of his western audiences, who were especially attracted by and familiar with western esoteric traditions and movements like Transcendentalism and New thought.[256]

In 1897 he founded the Ramakrishna Mission, which was instrumental in the spread of Neo-Vedanta in the west, and attracted people like Alan Watts. Aldous Huxley, author of The Perennial Philosophy, was associated with another neo-Vedanta organisation, the Vedanta Society of Southern California, founded and headed by Swami Prabhavananda. Together with Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood, and other followers he was initiated by the Swami and was taught meditation and spiritual practices.[257]

Theosophical Society

A major force in the mutual influence of eastern and western ideas and religiosity was the Theosophical Society.[258][259] It searched for ancient wisdom in the east, spreading eastern religious ideas in the west.[260] One of its salient features was the belief in "Masters of Wisdom",[261][note 30] "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of knowledge, and who make their wisdom available to others".[261] The Theosophical Society also spread western ideas in the east, aiding a modernisation of eastern traditions, and contributing to a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[212][note 31]New Age

The New Age movement is a Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational psychology, holistic health, parapsychology, consciousness research and quantum physics".[266] The New Age aims to create "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas" that is inclusive and pluralistic.[267] It holds to "a holistic worldview",[268] emphasising that the Mind, Body and Spirit are interrelated[269] and that there is a form of monism and unity throughout the universe.[web 31] It attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality"[270] and embraces a number of forms of mainstream science as well as other forms of science that are considered fringe.[citation needed]Scholarly debates

Nondual consciousness and mystical experience

Insight (prajna, kensho, satori, gnosis, theoria, illumination), especially enlightenment or the realization of the illusory nature of the autonomous "I" or self, is a key element in modern western nondual thought. It is the personal realization that ultimate reality is nondual, and is thought to be a validating means of knowledge of this nondual reality. This insight is interpreted as a psychological state, and labeled as religious or mystical experience.Development

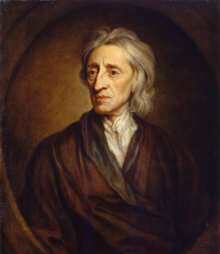

According to Hori, the notion of "religious experience" can be traced back to William James, who used the term "religious experience" in his book, The Varieties of Religious Experience.[271] The origins of the use of this term can be dated further back.[272]In the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, several historical figures put forth very influential views that religion and its beliefs can be grounded in experience itself. While Kant held that moral experience justified religious beliefs, John Wesley in addition to stressing individual moral exertion thought that the religious experiences in the Methodist movement (paralleling the Romantic Movement) were foundational to religious commitment as a way of life.[273]

Wayne Proudfoot traces the roots of the notion of "religious experience" to the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), who argued that religion is based on a feeling of the infinite. The notion of "religious experience" was used by Schleiermacher and Albert Ritschl to defend religion against the growing scientific and secular critique, and defend the view that human (moral and religious) experience justifies religious beliefs.[272]

Such religious empiricism would be later seen as highly problematic and was – during the period in-between world wars – famously rejected by Karl Barth.[274] In the 20th century, religious as well as moral experience as justification for religious beliefs still holds sway. Some influential modern scholars holding this liberal theological view are Charles Raven and the Oxford physicist/theologian Charles Coulson.[275]

The notion of "religious experience" was adopted by many scholars of religion, of which William James was the most influential.[276][note 32]

Criticism

The notion of "experience" has been criticised.[280][281][282] Robert Sharf points out that "experience" is a typical Western term, which has found its way into Asian religiosity via western influences.[280][note 33]Insight is not the "experience" of some transcendental reality, but is a cognitive event, the (intuitive) understanding or "grasping" of some specific understanding of reality, as in kensho[284] or anubhava.[285]

"Pure experience" does not exist; all experience is mediated by intellectual and cognitive activity.[286][287] A pure consciousness without concepts, reached by "cleaning the doors of perception",[note 34] would be an overwhelming chaos of sensory input without coherence.[288]

Nondual consciousness as common essence

Common essence

A main modern proponent of perennialism was Aldous Huxley, who was influenced by Vivekanda's Neo-Vedanta and Universalism.[257] This popular approach finds supports in the "common-core thesis". According to the "common-core thesis",[289] different descriptions can mask quite similar if not identical experiences:[290]According to Elias Amidon there is an "indescribable, but definitely recognizable, reality that is the ground of all being."[291] According to Renard, these are based on an experience or intuition of "the Real".[292] According to Amidon, this reality is signified by "many names" from "spiritual traditions throughout the world":[291]

[N]ondual awareness, pure awareness, open awareness, presence-awareness, unconditioned mind, rigpa, primordial experience, This, the basic state, the sublime, buddhanature, original nature, spontaneous presence, the oneness of being, the ground of being, the Real, clarity, God-consciousness, divine light, the clear light, illumination, realization and enlightenment.[291]According to Renard, nondualism as common essence prefers the term "nondualism", instead of monism, because this understanding is "nonconceptual", "not graspapable in an idea".[292][note 35] Even to call this "ground of reality", "One", or "Oneness" is attributing a characteristic to that ground of reality. The only thing that can be said is that it is "not two" or "non-dual":[web 33][293] According to Renard, Alan Watts has been one of the main contributors to the popularisation of the non-monistic understanding of "nondualism".[292][note 36]

Criticism

The "common-core thesis" is criticised by "diversity theorists" such as S.T Katz and W. Proudfoot.[290] They argue that[N]o unmediated experience is possible, and that in the extreme, language is not simply used to interpret experience but in fact constitutes experience.[290]The idea of a common essence has been questioned by Yandell, who discerns various "religious experiences" and their corresponding doctrinal settings, which differ in structure and phenomenological content, and in the "evidential value" they present.[295] Yandell discerns five sorts:[296]

- Numinous experiences – Monotheism (Jewish, Christian, Vedantic)[297]

- Nirvanic experiences – Buddhism,[298] "according to which one sees that the self is but a bundle of fleeting states"[299]

- Kevala experiences[300] – Jainism,[301] "according to which one sees the self as an indestructible subject of experience"[301]

- Moksha experiences[302] – Hinduism,[301] Brahman "either as a cosmic person, or, quite differently, as qualityless"[301]

- Nature mystical experience[300]