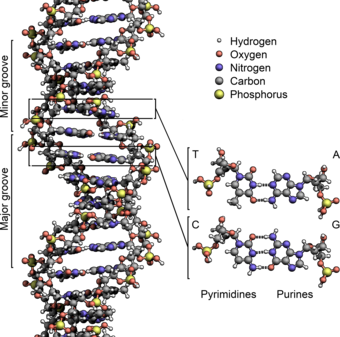

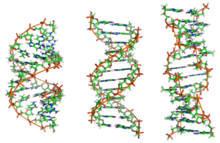

The structure of the DNA double helix. The atoms in the structure are colour-coded by element and the detailed structures of two base pairs are shown in the bottom right.

The structure of part of a DNA double helix

Deoxyribonucleic acid (/diˈɒksɪraɪboʊnjuːkliːɪk,

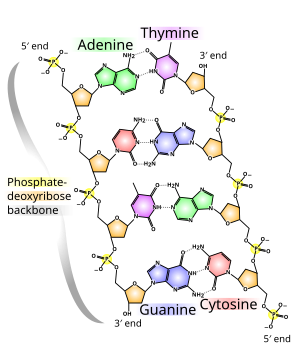

The two DNA strands are also known as polynucleotides as they are composed of simpler monomeric units called nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of one of four nitrogen-containing nucleobases (cytosine [C], guanine [G], adenine [A] or thymine [T]), a sugar called deoxyribose, and a phosphate group. The nucleotides are joined to one another in a chain by covalent bonds between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the next, resulting in an alternating sugar-phosphate backbone. The nitrogenous bases of the two separate polynucleotide strands are bound together, according to base pairing rules (A with T and C with G), with hydrogen bonds to make double-stranded DNA.

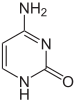

The complementary nitrogenous bases are divided into two groups, pyrimidines and purines. In DNA, the pyrimidines are thymine and cytosine; the purines are adenine and guanine.

Both strands of double-stranded DNA store the same biological information. This information is replicated as and when the two strands separate. A large part of DNA (more than 98% for humans) is non-coding, meaning that these sections do not serve as patterns for protein sequences.

The two strands of DNA run in opposite directions to each other and are thus antiparallel. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of nucleobases (informally, bases). It is the sequence of these four nucleobases along the backbone that encodes genetic information. RNA strands are created using DNA strands as a template in a process called transcription. Under the genetic code, these RNA strands specify the sequence of amino acids within proteins in a process called translation.

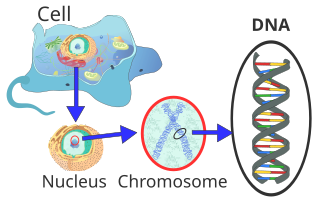

Within eukaryotic cells, DNA is organized into long structures called chromosomes. Before typical cell division, these chromosomes are duplicated in the process of DNA replication, providing a complete set of chromosomes for each daughter cell. Eukaryotic organisms (animals, plants, fungi and protists) store most of their DNA inside the cell nucleus and some in organelles, such as mitochondria or chloroplasts. In contrast, prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) store their DNA only in the cytoplasm. Within eukaryotic chromosomes, chromatin proteins, such as histones,

compact and organize DNA. These compact structures guide the

interactions between DNA and other proteins, helping control which parts

of the DNA are transcribed.

DNA was first isolated by Friedrich Miescher in 1869. Its molecular structure was first identified by James Watson and Francis Crick at the Cavendish Laboratory within the University of Cambridge in 1953, whose model-building efforts were guided by X-ray diffraction data acquired by Raymond Gosling, who was a post-graduate student of Rosalind Franklin. DNA is used by researchers as a molecular tool to explore physical laws and theories, such as the ergodic theorem and the theory of elasticity.

The unique material properties of DNA have made it an attractive

molecule for material scientists and engineers interested in micro- and

nano-fabrication. Among notable advances in this field are DNA origami and DNA-based hybrid materials.

Properties

Chemical structure of DNA; hydrogen bonds shown as dotted lines

DNA is a long polymer made from repeating units called nucleotides. The structure of DNA is dynamic along its length, being capable of coiling into tight loops and other shapes. In all species it is composed of two helical chains, bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. Both chains are coiled around the same axis, and have the same pitch of 34 ångströms (3.4 nanometres). The pair of chains has a radius of 10 ångströms (1.0 nanometre).

According to another study, when measured in a different solution, the

DNA chain measured 22 to 26 ångströms wide (2.2 to 2.6 nanometres), and

one nucleotide unit measured 3.3 Å (0.33 nm) long.

Although each individual nucleotide repeating unit is very small, DNA

polymers can be very large molecules containing hundreds of millions of

nucleotides. For instance, the DNA in the largest human chromosome, chromosome number 1, consists of approximately 220 million base pairs and would be 85 mm long if straightened.

In living organisms, DNA does not usually exist as a single

strand, but instead as a pair of strands that are held tightly together. These two long strands entwine like vines, in the shape of a double helix.

The nucleotide contains both a segment of the backbone of the molecule

(which holds the chain together) and a nucleobase (which interacts with

the other DNA strand in the helix). A nucleobase linked to a sugar is

called a nucleoside and a base linked to a sugar and one or more phosphate groups is called a nucleotide. A polymer comprising multiple linked nucleotides (as in DNA) is called a polynucleotide.

The backbone of the DNA strand is made from alternating phosphate and sugar residues. The sugar in DNA is 2-deoxyribose, which is a pentose (five-carbon) sugar. The sugars are joined together by phosphate groups that form phosphodiester bonds between the third and fifth carbon atoms

of adjacent sugar rings, which are known as the 3′ and 5′ carbons, the

prime symbol being used to distinguish these carbon atoms from those of

the base to which the deoxyribose forms a glycosidic bond.

When imagining DNA, each phosphoryl is normally considered to "belong"

to the nucleotide whose 5′ carbon forms a bond therewith. Any DNA strand

therefore normally has one end at which there is a phosphoryl attached

to the 5′ carbon of a ribose (the 5′ phosphoryl) and another end at

which there is a free hydroxyl attached to the 3′ carbon of a ribose

(the 3′ hydroxyl). The orientation of the 3′ and 5′ carbons along the

sugar-phosphate backbone confers directionality (sometimes called

polarity) to each DNA strand. In a double helix, the direction of the

nucleotides in one strand is opposite to their direction in the other

strand: the strands are antiparallel. The asymmetric ends of DNA strands are said to have a directionality of five prime (5′) and three prime

(3′), with the 5′ end having a terminal phosphate group and the 3′ end a

terminal hydroxyl group. One major difference between DNA and RNA is the sugar, with the 2-deoxyribose in DNA being replaced by the alternative pentose sugar ribose in RNA.

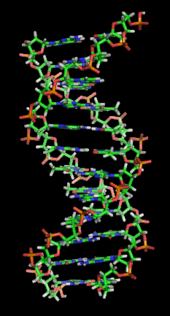

A section of DNA. The bases lie horizontally between the two spiraling strands (animated version).

The DNA double helix is stabilized primarily by two forces: hydrogen bonds between nucleotides and base-stacking interactions among aromatic nucleobases. In the aqueous environment of the cell, the conjugated π bonds of nucleotide bases align perpendicular to the axis of the DNA molecule, minimizing their interaction with the solvation shell. The four bases found in DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). These four bases are attached to the sugar-phosphate to form the complete nucleotide, as shown for adenosine monophosphate. Adenine pairs with thymine and guanine pairs with cytosine, forming A-T and G-C base pairs.

Nucleobase classification

The nucleobases are classified into two types: the purines, A and G, which are fused five- and six-membered heterocyclic compounds, and the pyrimidines, the six-membered rings C and T. A fifth pyrimidine nucleobase, uracil (U), usually takes the place of thymine in RNA and differs from thymine by lacking a methyl group on its ring. In addition to RNA and DNA, many artificial nucleic acid analogues have been created to study the properties of nucleic acids, or for use in biotechnology.

Non-canonical bases

Uracil is not usually found in DNA, occurring only as a breakdown

product of cytosine. However, in several bacteriophages, such as Bacillus subtilis bacteriophages PBS1 and PBS2 and Yersinia bacteriophage piR1-37, thymine has been replaced by uracil. Another phage - Staphylococcal phage S6 - has been identified with a genome where thymine has been replaced by uracil.

Uracil is also found in the DNA of Plasmodium falciparum It is present is relatively small amounts (7-10 uracil residues per million bases).

5-hydroxymethyldeoxyuridine,(hm5dU) is also known to replace thymidine in several genomes including the Bacillus phages SPO1, ϕe, SP8, H1, 2C and SP82. Another modified uracil - 5-dihydroxypentauracil – has also been described.

Base J (beta-d-glucopyranosyloxymethyluracil), a modified form of uracil, is also found in several organisms: the flagellates Diplonema and Euglena, and all the kinetoplastid genera. Biosynthesis

of J occurs in two steps: in the first step, a specific thymidine in

DNA is converted into hydroxymethyldeoxyuridine; in the second, HOMedU

is glycosylated to form J. Proteins that bind specifically to this base have been identified. These proteins appear to be distant relatives of the Tet1 oncogene that is involved in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia. J appears to act as a termination signal for RNA polymerase II.

In 1976, the S-2La bacteriophage, which infects species of the genus Synechocystis, was found to have all the adenosine bases within its genome replaced by 2,6-diaminopurine. In 2016 deoxyarchaeosine was found to be present in the genomes of several bacteria and the Escherichia phage 9g.

Modified bases also occur in DNA. The first of these recognised was 5-methylcytosine, which was found in the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1925. The complete replacement of cytosine by 5-glycosylhydroxymethylcytosine in T even phages (T2, T4 and T6) was observed in 1953. In the genomes of Xanthomonas oryzae bacteriophage Xp12 and halovirus FH the full complement of cystosine has been replaced by 5-methylcytosine. 6N-methyladenine was discovered to be present in DNA in 1955. N6-carbamoyl-methyladenine was described in 1975. 7-methylguanine was described in 1976. N4-methylcytosine in DNA was described in 1983. In 1985 5-hydroxycytosine was found in the genomes of the Rhizobium phages RL38JI and N17. α-putrescinylthymine occurs in both the genomes of the Delftia phage ΦW-14 and the Bacillus phage SP10. α-glutamylthymidine is found in the Bacillus phage SP01 and 5-dihydroxypentyluracil is found in the Bacillus phage SP15.

The reason for the presence of these non canonical bases in DNA

is not known. It seems likely that at least part of the reason for their

presence in bacterial viruses (phages) is to avoid the restriction enzymes

present in bacteria. This enzyme system acts at least in part as a

molecular immune system protecting bacteria from infection by viruses.

This does not appear to be the entire story. Four modifications to the cytosine residues in human DNA have been reported. These modifications are the addition of methyl (CH3)-, hydroxymethyl (CH2OH)-, formyl (CHO)- and carboxyl (COOH)- groups. These modifications are thought to have regulatory functions.

Uracil is found in the centromeric regions of at least two human chromosomes (6 and 11).

Listing of non canonical bases found in DNA

Seventeen non canonical bases are known to occur in DNA. Most of these are modifications of the canonical bases plus uracil.

- Modified Adenosine

- N6-carbamoyl-methyladenine

- N6-methyadenine

- Modified Guanine

- 7-Methylguanine

- Modified Cytosine

- N4-Methylcytosine

- 5-Carboxylcytosine

- 5-Formylcytosine

- 5-Glycosylhydroxymethylcytosine

- 5-Hydroxycytosine

- 5-Methylcytosine

- Modified Thymidine

- α-Glutamythymidine

- α-Putrescinylthymine

- Uracil and modifications

- Base J

- Uracil

- 5-Dihydroxypentauracil

- 5-Hydroxymethyldeoxyuracil

- Others

- Deoxyarchaeosine

- 2,6-Diaminopurine

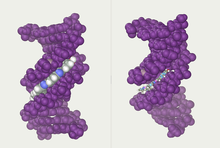

DNA major and minor grooves. The latter is a binding site for the Hoechst stain dye 33258.

Grooves

Twin helical strands form the DNA backbone. Another double helix may

be found tracing the spaces, or grooves, between the strands. These

voids are adjacent to the base pairs and may provide a binding site.

As the strands are not symmetrically located with respect to each

other, the grooves are unequally sized. One groove, the major groove, is

22 Å wide and the other, the minor groove, is 12 Å wide.

The width of the major groove means that the edges of the bases are

more accessible in the major groove than in the minor groove. As a

result, proteins such as transcription factors

that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make

contact with the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove. This situation varies in unusual conformations of DNA within the cell (see below),

but the major and minor grooves are always named to reflect the

differences in size that would be seen if the DNA is twisted back into

the ordinary B form.

Base pairing

In a DNA double helix, each type of nucleobase on one strand bonds

with just one type of nucleobase on the other strand. This is called

complementary base pairing. Here, purines form hydrogen bonds

to pyrimidines, with adenine bonding only to thymine in two hydrogen

bonds, and cytosine bonding only to guanine in three hydrogen bonds.

This arrangement of two nucleotides binding together across the double

helix is called a Watson-Crick base pair. Another type of base pairing

is Hoogsteen base pairing where two hydrogen bonds form between guanine

and cytosine. As hydrogen bonds are not covalent,

they can be broken and rejoined relatively easily. The two strands of

DNA in a double helix can thus be pulled apart like a zipper, either by a

mechanical force or high temperature.

As a result of this base pair complementarity, all the information in

the double-stranded sequence of a DNA helix is duplicated on each

strand, which is vital in DNA replication. This reversible and specific

interaction between complementary base pairs is critical for all the

functions of DNA in living organisms.

|

|

Top, a GC base pair with three hydrogen bonds. Bottom, an AT base pair with two hydrogen bonds. Non-covalent hydrogen bonds between the pairs are shown as dashed lines.

The two types of base pairs form different numbers of hydrogen bonds,

AT forming two hydrogen bonds, and GC forming three hydrogen bonds (see

figures, right).

DNA with high GC-content is more stable than DNA with low GC-content.

As noted above, most DNA molecules are actually two polymer strands,

bound together in a helical fashion by noncovalent bonds; this

double-stranded (dsDNA) structure is maintained largely by the

intrastrand base stacking interactions, which are strongest for G,C

stacks. The two strands can come apart – a process known as melting – to

form two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules. Melting occurs at high temperature, low salt and high pH (low pH also melts DNA, but since DNA is unstable due to acid depurination, low pH is rarely used).

The stability of the dsDNA form depends not only on the

GC-content (% G,C basepairs) but also on sequence (since stacking is

sequence specific) and also length (longer molecules are more stable).

The stability can be measured in various ways; a common way is the

"melting temperature", which is the temperature at which 50% of the ds

molecules are converted to ss molecules; melting temperature is

dependent on ionic strength and the concentration of DNA. As a result,

it is both the percentage of GC base pairs and the overall length of a

DNA double helix that determines the strength of the association between

the two strands of DNA. Long DNA helices with a high GC-content have

stronger-interacting strands, while short helices with high AT content

have weaker-interacting strands. In biology, parts of the DNA double helix that need to separate easily, such as the TATAAT Pribnow box in some promoters, tend to have a high AT content, making the strands easier to pull apart.

In the laboratory, the strength of this interaction can be

measured by finding the temperature necessary to break the hydrogen

bonds, their melting temperature (also called Tm

value). When all the base pairs in a DNA double helix melt, the strands

separate and exist in solution as two entirely independent molecules.

These single-stranded DNA molecules have no single common shape, but

some conformations are more stable than others.

Sense and antisense

A DNA sequence is called "sense" if its sequence is the same as that of a messenger RNA copy that is translated into protein.

The sequence on the opposite strand is called the "antisense" sequence.

Both sense and antisense sequences can exist on different parts of the

same strand of DNA (i.e. both strands can contain both sense and

antisense sequences). In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, antisense RNA

sequences are produced, but the functions of these RNAs are not entirely

clear. One proposal is that antisense RNAs are involved in regulating gene expression through RNA-RNA base pairing.

A few DNA sequences in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and more in plasmids and viruses, blur the distinction between sense and antisense strands by having overlapping genes.

In these cases, some DNA sequences do double duty, encoding one protein

when read along one strand, and a second protein when read in the

opposite direction along the other strand. In bacteria, this overlap may be involved in the regulation of gene transcription, while in viruses, overlapping genes increase the amount of information that can be encoded within the small viral genome.

Supercoiling

DNA can be twisted like a rope in a process called DNA supercoiling.

With DNA in its "relaxed" state, a strand usually circles the axis of

the double helix once every 10.4 base pairs, but if the DNA is twisted

the strands become more tightly or more loosely wound.

If the DNA is twisted in the direction of the helix, this is positive

supercoiling, and the bases are held more tightly together. If they are

twisted in the opposite direction, this is negative supercoiling, and

the bases come apart more easily. In nature, most DNA has slight

negative supercoiling that is introduced by enzymes called topoisomerases. These enzymes are also needed to relieve the twisting stresses introduced into DNA strands during processes such as transcription and DNA replication.

From left to right, the structures of A, B and Z DNA

Alternative DNA structures

DNA exists in many possible conformations that include A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA forms, although, only B-DNA and Z-DNA have been directly observed in functional organisms.

The conformation that DNA adopts depends on the hydration level, DNA

sequence, the amount and direction of supercoiling, chemical

modifications of the bases, the type and concentration of metal ions, and the presence of polyamines in solution.

The first published reports of A-DNA X-ray diffraction patterns—and also B-DNA—used analyses based on Patterson transforms that provided only a limited amount of structural information for oriented fibers of DNA. An alternative analysis was then proposed by Wilkins et al., in 1953, for the in vivo B-DNA X-ray diffraction-scattering patterns of highly hydrated DNA fibers in terms of squares of Bessel functions. In the same journal, James Watson and Francis Crick presented their molecular modeling analysis of the DNA X-ray diffraction patterns to suggest that the structure was a double-helix.

Although the B-DNA form is most common under the conditions found in cells, it is not a well-defined conformation but a family of related DNA conformations

that occur at the high hydration levels present in living cells. Their

corresponding X-ray diffraction and scattering patterns are

characteristic of molecular paracrystals with a significant degree of disorder.

Compared to B-DNA, the A-DNA form is a wider right-handed

spiral, with a shallow, wide minor groove and a narrower, deeper major

groove. The A form occurs under non-physiological conditions in partly

dehydrated samples of DNA, while in the cell it may be produced in

hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, and in enzyme-DNA complexes. Segments of DNA where the bases have been chemically modified by methylation may undergo a larger change in conformation and adopt the Z form. Here, the strands turn about the helical axis in a left-handed spiral, the opposite of the more common B form.

These unusual structures can be recognized by specific Z-DNA binding

proteins and may be involved in the regulation of transcription.

Alternative DNA chemistry

For many years, exobiologists have proposed the existence of a shadow biosphere,

a postulated microbial biosphere of Earth that uses radically different

biochemical and molecular processes than currently known life. One of

the proposals was the existence of lifeforms that use arsenic instead of phosphorus in DNA. A report in 2010 of the possibility in the bacterium GFAJ-1, was announced, though the research was disputed,

and evidence suggests the bacterium actively prevents the incorporation

of arsenic into the DNA backbone and other biomolecules.

Quadruplex structures

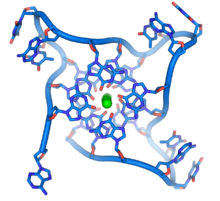

At the ends of the linear chromosomes are specialized regions of DNA called telomeres. The main function of these regions is to allow the cell to replicate chromosome ends using the enzyme telomerase, as the enzymes that normally replicate DNA cannot copy the extreme 3′ ends of chromosomes. These specialized chromosome caps also help protect the DNA ends, and stop the DNA repair systems in the cell from treating them as damage to be corrected. In human cells, telomeres are usually lengths of single-stranded DNA containing several thousand repeats of a simple TTAGGG sequence.

DNA quadruplex formed by telomere

repeats. The looped conformation of the DNA backbone is very different

from the typical DNA helix. The green spheres in the center represent

potassium ions.

These guanine-rich sequences may stabilize chromosome ends by forming

structures of stacked sets of four-base units, rather than the usual

base pairs found in other DNA molecules. Here, four guanine bases form a

flat plate and these flat four-base units then stack on top of each

other, to form a stable G-quadruplex structure. These structures are stabilized by hydrogen bonding between the edges of the bases and chelation of a metal ion in the centre of each four-base unit.

Other structures can also be formed, with the central set of four bases

coming from either a single strand folded around the bases, or several

different parallel strands, each contributing one base to the central

structure.

In addition to these stacked structures, telomeres also form

large loop structures called telomere loops, or T-loops. Here, the

single-stranded DNA curls around in a long circle stabilized by

telomere-binding proteins.

At the very end of the T-loop, the single-stranded telomere DNA is held

onto a region of double-stranded DNA by the telomere strand disrupting

the double-helical DNA and base pairing to one of the two strands. This triple-stranded structure is called a displacement loop or D-loop.

|

| Top: single branch. Bottom: Multiple branches. |

Branched DNA can form networks containing multiple branches.

Branched DNA

In DNA, fraying

occurs when non-complementary regions exist at the end of an otherwise

complementary double-strand of DNA. However, branched DNA can occur if a

third strand of DNA is introduced and contains adjoining regions able

to hybridize with the frayed regions of the pre-existing double-strand.

Although the simplest example of branched DNA involves only three

strands of DNA, complexes involving additional strands and multiple

branches are also possible. Branched DNA can be used in nanotechnology to construct geometric shapes, see the section on uses in technology below.

Chemical modifications and altered DNA packaging

|

|

|

| cytosine | 5-methylcytosine | thymine |

Structure of cytosine with and without the 5-methyl group. Deamination converts 5-methylcytosine into thymine.

Base modifications and DNA packaging

The expression of genes is influenced by how the DNA is packaged in chromosomes, in a structure called chromatin.

Base modifications can be involved in packaging, with regions that have

low or no gene expression usually containing high levels of methylation of cytosine bases. DNA packaging and its influence on gene expression can also occur by covalent modifications of the histone

protein core around which DNA is wrapped in the chromatin structure or

else by remodeling carried out by chromatin remodeling complexes (see Chromatin remodeling). There is, further, crosstalk between DNA methylation and histone modification, so they can coordinately affect chromatin and gene expression.

For one example, cytosine methylation produces 5-methylcytosine, which is important for X-inactivation of chromosomes. The average level of methylation varies between organisms – the worm Caenorhabditis elegans lacks cytosine methylation, while vertebrates have higher levels, with up to 1% of their DNA containing 5-methylcytosine. Despite the importance of 5-methylcytosine, it can deaminate to leave a thymine base, so methylated cytosines are particularly prone to mutations. Other base modifications include adenine methylation in bacteria, the presence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the brain, and the glycosylation of uracil to produce the "J-base" in kinetoplastids.

Damage

A covalent adduct between a metabolically activated form of benzo[a]pyrene, the major mutagen in tobacco smoke, and DNA

DNA can be damaged by many sorts of mutagens, which change the DNA sequence. Mutagens include oxidizing agents, alkylating agents and also high-energy electromagnetic radiation such as ultraviolet light and X-rays. The type of DNA damage produced depends on the type of mutagen. For example, UV light can damage DNA by producing thymine dimers, which are cross-links between pyrimidine bases. On the other hand, oxidants such as free radicals or hydrogen peroxide produce multiple forms of damage, including base modifications, particularly of guanosine, and double-strand breaks. A typical human cell contains about 150,000 bases that have suffered oxidative damage. Of these oxidative lesions, the most dangerous are double-strand breaks, as these are difficult to repair and can produce point mutations, insertions, deletions from the DNA sequence, and chromosomal translocations. These mutations can cause cancer.

Because of inherent limits in the DNA repair mechanisms, if humans

lived long enough, they would all eventually develop cancer. DNA damages that are naturally occurring,

due to normal cellular processes that produce reactive oxygen species,

the hydrolytic activities of cellular water, etc., also occur

frequently. Although most of these damages are repaired, in any cell

some DNA damage may remain despite the action of repair processes. These

remaining DNA damages accumulate with age in mammalian postmitotic

tissues. This accumulation appears to be an important underlying cause

of aging.

Many mutagens fit into the space between two adjacent base pairs, this is called intercalation. Most intercalators are aromatic and planar molecules; examples include ethidium bromide, acridines, daunomycin, and doxorubicin.

For an intercalator to fit between base pairs, the bases must separate,

distorting the DNA strands by unwinding of the double helix. This

inhibits both transcription and DNA replication, causing toxicity and

mutations. As a result, DNA intercalators may be carcinogens, and in the case of thalidomide, a teratogen. Others such as benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide and aflatoxin form DNA adducts that induce errors in replication. Nevertheless, due to their ability to inhibit DNA transcription and replication, other similar toxins are also used in chemotherapy to inhibit rapidly growing cancer cells.

Biological functions

Location of eukaryote nuclear DNA within the chromosomes

DNA usually occurs as linear chromosomes in eukaryotes, and circular chromosomes in prokaryotes. The set of chromosomes in a cell makes up its genome; the human genome has approximately 3 billion base pairs of DNA arranged into 46 chromosomes. The information carried by DNA is held in the sequence of pieces of DNA called genes. Transmission

of genetic information in genes is achieved via complementary base

pairing. For example, in transcription, when a cell uses the information

in a gene, the DNA sequence is copied into a complementary RNA sequence

through the attraction between the DNA and the correct RNA nucleotides.

Usually, this RNA copy is then used to make a matching protein sequence in a process called translation,

which depends on the same interaction between RNA nucleotides. In

alternative fashion, a cell may simply copy its genetic information in a

process called DNA replication. The details of these functions are

covered in other articles; here the focus is on the interactions between

DNA and other molecules that mediate the function of the genome.

Genes and genomes

Genomic DNA is tightly and orderly packed in the process called DNA condensation, to fit the small available volumes of the cell. In eukaryotes, DNA is located in the cell nucleus, with small amounts in mitochondria and chloroplasts. In prokaryotes, the DNA is held within an irregularly shaped body in the cytoplasm called the nucleoid.

The genetic information in a genome is held within genes, and the

complete set of this information in an organism is called its genotype. A gene is a unit of heredity and is a region of DNA that influences a particular characteristic in an organism. Genes contain an open reading frame that can be transcribed, and regulatory sequences such as promoters and enhancers, which control transcription of the open reading frame.

In many species, only a small fraction of the total sequence of the genome encodes protein. For example, only about 1.5% of the human genome consists of protein-coding exons, with over 50% of human DNA consisting of non-coding repetitive sequences. The reasons for the presence of so much noncoding DNA in eukaryotic genomes and the extraordinary differences in genome size, or C-value, among species, represent a long-standing puzzle known as the "C-value enigma". However, some DNA sequences that do not code protein may still encode functional non-coding RNA molecules, which are involved in the regulation of gene expression.

T7 RNA polymerase (blue) producing an mRNA (green) from a DNA template (orange)

Some noncoding DNA sequences play structural roles in chromosomes. Telomeres and centromeres typically contain few genes but are important for the function and stability of chromosomes. An abundant form of noncoding DNA in humans are pseudogenes, which are copies of genes that have been disabled by mutation. These sequences are usually just molecular fossils, although they can occasionally serve as raw genetic material for the creation of new genes through the process of gene duplication and divergence.

Transcription and translation

A gene is a sequence of DNA that contains genetic information and can influence the phenotype of an organism. Within a gene, the sequence of bases along a DNA strand defines a messenger RNA sequence, which then defines one or more protein sequences. The relationship between the nucleotide sequences of genes and the amino-acid sequences of proteins is determined by the rules of translation, known collectively as the genetic code. The genetic code consists of three-letter 'words' called codons formed from a sequence of three nucleotides (e.g. ACT, CAG, TTT).

In transcription, the codons of a gene are copied into messenger RNA by RNA polymerase. This RNA copy is then decoded by a ribosome that reads the RNA sequence by base-pairing the messenger RNA to transfer RNA, which carries amino acids. Since there are 4 bases in 3-letter combinations, there are 64 possible codons (43 combinations). These encode the twenty standard amino acids,

giving most amino acids more than one possible codon. There are also

three 'stop' or 'nonsense' codons signifying the end of the coding

region; these are the TAA, TGA, and TAG codons.

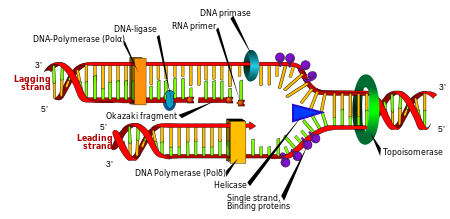

DNA replication. The double helix is unwound by a helicase and topoisomerase. Next, one DNA polymerase produces the leading strand copy. Another DNA polymerase binds to the lagging strand. This enzyme makes discontinuous segments (called Okazaki fragments) before DNA ligase joins them together.

Replication

Cell division

is essential for an organism to grow, but, when a cell divides, it must

replicate the DNA in its genome so that the two daughter cells have the

same genetic information as their parent. The double-stranded structure

of DNA provides a simple mechanism for DNA replication. Here, the two strands are separated and then each strand's complementary DNA sequence is recreated by an enzyme called DNA polymerase.

This enzyme makes the complementary strand by finding the correct base

through complementary base pairing and bonding it onto the original

strand. As DNA polymerases can only extend a DNA strand in a 5′ to 3′

direction, different mechanisms are used to copy the antiparallel

strands of the double helix.

In this way, the base on the old strand dictates which base appears on

the new strand, and the cell ends up with a perfect copy of its DNA.

Extracellular nucleic acids

Naked extracellular DNA (eDNA), most of it released by cell death, is

nearly ubiquitous in the environment. Its concentration in soil may be

as high as 2 μg/L, and its concentration in natural aquatic environments

may be as high at 88 μg/L. Various possible functions have been proposed for eDNA: it may be involved in horizontal gene transfer; it may provide nutrients; and it may act as a buffer to recruit or titrate ions or antibiotics. Extracellular DNA acts as a functional extracellular matrix component in the biofilms

of several bacterial species. It may act as a recognition factor to

regulate the attachment and dispersal of specific cell types in the

biofilm; it may contribute to biofilm formation; and it may contribute to the biofilm's physical strength and resistance to biological stress.

Cell-free fetal DNA is found in the blood of the mother, and can be sequenced to determine a great deal of information about the developing fetus.

Interactions with proteins

All the functions of DNA depend on interactions with proteins. These protein interactions

can be non-specific, or the protein can bind specifically to a single

DNA sequence. Enzymes can also bind to DNA and of these, the polymerases

that copy the DNA base sequence in transcription and DNA replication

are particularly important.

DNA-binding proteins

|

Interaction of DNA (in orange) with histones (in blue). These proteins' basic amino acids bind to the acidic phosphate groups on DNA.

Structural proteins that bind DNA are well-understood examples of

non-specific DNA-protein interactions. Within chromosomes, DNA is held

in complexes with structural proteins. These proteins organize the DNA

into a compact structure called chromatin. In eukaryotes, this structure involves DNA binding to a complex of small basic proteins called histones, while in prokaryotes multiple types of proteins are involved. The histones form a disk-shaped complex called a nucleosome,

which contains two complete turns of double-stranded DNA wrapped around

its surface. These non-specific interactions are formed through basic

residues in the histones, making ionic bonds to the acidic sugar-phosphate backbone of the DNA, and are thus largely independent of the base sequence. Chemical modifications of these basic amino acid residues include methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation.

These chemical changes alter the strength of the interaction between

the DNA and the histones, making the DNA more or less accessible to transcription factors and changing the rate of transcription.

Other non-specific DNA-binding proteins in chromatin include the

high-mobility group proteins, which bind to bent or distorted DNA.

These proteins are important in bending arrays of nucleosomes and

arranging them into the larger structures that make up chromosomes.

A distinct group of DNA-binding proteins is the DNA-binding

proteins that specifically bind single-stranded DNA. In humans,

replication protein A

is the best-understood member of this family and is used in processes

where the double helix is separated, including DNA replication,

recombination, and DNA repair. These binding proteins seem to stabilize single-stranded DNA and protect it from forming stem-loops or being degraded by nucleases.

The lambda repressor helix-turn-helix transcription factor bound to its DNA target

In contrast, other proteins have evolved to bind to particular DNA

sequences. The most intensively studied of these are the various transcription factors,

which are proteins that regulate transcription. Each transcription

factor binds to one particular set of DNA sequences and activates or

inhibits the transcription of genes that have these sequences close to

their promoters. The transcription factors do this in two ways. Firstly,

they can bind the RNA polymerase responsible for transcription, either

directly or through other mediator proteins; this locates the polymerase

at the promoter and allows it to begin transcription. Alternatively, transcription factors can bind enzymes that modify the histones at the promoter. This changes the accessibility of the DNA template to the polymerase.

As these DNA targets can occur throughout an organism's genome,

changes in the activity of one type of transcription factor can affect

thousands of genes. Consequently, these proteins are often the targets of the signal transduction processes that control responses to environmental changes or cellular differentiation

and development. The specificity of these transcription factors'

interactions with DNA come from the proteins making multiple contacts to

the edges of the DNA bases, allowing them to "read" the DNA sequence.

Most of these base-interactions are made in the major groove, where the

bases are most accessible.

The restriction enzyme EcoRV (green) in a complex with its substrate DNA

DNA-modifying enzymes

Nucleases and ligases

Nucleases are enzymes that cut DNA strands by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds. Nucleases that hydrolyse nucleotides from the ends of DNA strands are called exonucleases, while endonucleases cut within strands. The most frequently used nucleases in molecular biology are the restriction endonucleases,

which cut DNA at specific sequences. For instance, the EcoRV enzyme

shown to the left recognizes the 6-base sequence 5′-GATATC-3′ and makes a

cut at the horizontal line. In nature, these enzymes protect bacteria against phage infection by digesting the phage DNA when it enters the bacterial cell, acting as part of the restriction modification system. In technology, these sequence-specific nucleases are used in molecular cloning and DNA fingerprinting.

Enzymes called DNA ligases can rejoin cut or broken DNA strands. Ligases are particularly important in lagging strand DNA replication, as they join together the short segments of DNA produced at the replication fork into a complete copy of the DNA template. They are also used in DNA repair and genetic recombination.

Topoisomerases and helicases

Topoisomerases are enzymes with both nuclease and ligase activity. These proteins change the amount of supercoiling

in DNA. Some of these enzymes work by cutting the DNA helix and

allowing one section to rotate, thereby reducing its level of

supercoiling; the enzyme then seals the DNA break.

Other types of these enzymes are capable of cutting one DNA helix and

then passing a second strand of DNA through this break, before rejoining

the helix. Topoisomerases are required for many processes involving DNA, such as DNA replication and transcription.

Helicases are proteins that are a type of molecular motor. They use the chemical energy in nucleoside triphosphates, predominantly adenosine triphosphate (ATP), to break hydrogen bonds between bases and unwind the DNA double helix into single strands. These enzymes are essential for most processes where enzymes need to access the DNA bases.

Polymerases

Polymerases are enzymes that synthesize polynucleotide chains from nucleoside triphosphates. The sequence of their products is created based on existing polynucleotide chains—which are called templates. These enzymes function by repeatedly adding a nucleotide to the 3′ hydroxyl group at the end of the growing polynucleotide chain. As a consequence, all polymerases work in a 5′ to 3′ direction. In the active site

of these enzymes, the incoming nucleoside triphosphate base-pairs to

the template: this allows polymerases to accurately synthesize the

complementary strand of their template. Polymerases are classified

according to the type of template that they use.

In DNA replication, DNA-dependent DNA polymerases

make copies of DNA polynucleotide chains. To preserve biological

information, it is essential that the sequence of bases in each copy are

precisely complementary to the sequence of bases in the template

strand. Many DNA polymerases have a proofreading

activity. Here, the polymerase recognizes the occasional mistakes in

the synthesis reaction by the lack of base pairing between the

mismatched nucleotides. If a mismatch is detected, a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity is activated and the incorrect base removed. In most organisms, DNA polymerases function in a large complex called the replisome that contains multiple accessory subunits, such as the DNA clamp or helicases.

RNA-dependent DNA polymerases are a specialized class of

polymerases that copy the sequence of an RNA strand into DNA. They

include reverse transcriptase, which is a viral enzyme involved in the infection of cells by retroviruses, and telomerase, which is required for the replication of telomeres. For example, HIV reverse transcriptase is an enzyme for AIDS virus replication. Telomerase is an unusual polymerase because it contains its own RNA template as part of its structure. It synthesizes telomeres

at the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres prevent fusion of the ends of

neighboring chromosomes and protect chromosome ends from damage.

Transcription is carried out by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase

that copies the sequence of a DNA strand into RNA. To begin

transcribing a gene, the RNA polymerase binds to a sequence of DNA

called a promoter and separates the DNA strands. It then copies the gene

sequence into a messenger RNA transcript until it reaches a region of DNA called the terminator, where it halts and detaches from the DNA. As with human DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, RNA polymerase II, the enzyme that transcribes most of the genes in the human genome, operates as part of a large protein complex with multiple regulatory and accessory subunits.

Genetic recombination

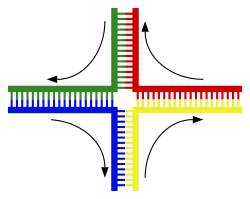

|

|

Structure of the Holliday junction intermediate in genetic recombination. The four separate DNA strands are coloured red, blue, green and yellow.

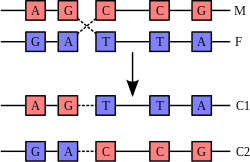

Recombination

involves the breaking and rejoining of two chromosomes (M and F) to

produce two rearranged chromosomes (C1 and C2).

A DNA helix usually does not interact with other segments of DNA, and

in human cells, the different chromosomes even occupy separate areas in

the nucleus called "chromosome territories".

This physical separation of different chromosomes is important for the

ability of DNA to function as a stable repository for information, as

one of the few times chromosomes interact is in chromosomal crossover which occurs during sexual reproduction, when genetic recombination occurs. Chromosomal crossover is when two DNA helices break, swap a section and then rejoin.

Recombination allows chromosomes to exchange genetic information

and produces new combinations of genes, which increases the efficiency

of natural selection and can be important in the rapid evolution of new proteins. Genetic recombination can also be involved in DNA repair, particularly in the cell's response to double-strand breaks.

The most common form of chromosomal crossover is homologous recombination, where the two chromosomes involved share very similar sequences. Non-homologous recombination can be damaging to cells, as it can produce chromosomal translocations and genetic abnormalities. The recombination reaction is catalyzed by enzymes known as recombinases, such as RAD51. The first step in recombination is a double-stranded break caused by either an endonuclease or damage to the DNA. A series of steps catalyzed in part by the recombinase then leads to joining of the two helices by at least one Holliday junction,

in which a segment of a single strand in each helix is annealed to the

complementary strand in the other helix. The Holliday junction is a

tetrahedral junction structure that can be moved along the pair of

chromosomes, swapping one strand for another. The recombination reaction

is then halted by cleavage of the junction and re-ligation of the

released DNA. Only strands of like polarity exchange DNA during recombination. There

are two types of cleavage: east-west cleavage and north-south cleavage.

The north-south cleavage nicks both strands of DNA, while the east-west

cleavage has one strand of DNA intact. The formation of a Holliday

junction during recombination makes it possible for genetic diversity,

genes to exchange on chromosomes, and expression of wild-type viral

genomes.

Evolution

DNA contains the genetic information that allows all modern living

things to function, grow and reproduce. However, it is unclear how long

in the 4-billion-year history of life

DNA has performed this function, as it has been proposed that the

earliest forms of life may have used RNA as their genetic material. RNA may have acted as the central part of early cell metabolism as it can both transmit genetic information and carry out catalysis as part of ribozymes. This ancient RNA world where nucleic acid would have been used for both catalysis and genetics may have influenced the evolution

of the current genetic code based on four nucleotide bases. This would

occur, since the number of different bases in such an organism is a

trade-off between a small number of bases increasing replication

accuracy and a large number of bases increasing the catalytic efficiency

of ribozymes.

However, there is no direct evidence of ancient genetic systems, as

recovery of DNA from most fossils is impossible because DNA survives in

the environment for less than one million years, and slowly degrades

into short fragments in solution.

Claims for older DNA have been made, most notably a report of the

isolation of a viable bacterium from a salt crystal 250 million years

old, but these claims are controversial.

Building blocks of DNA (adenine, guanine, and related organic molecules) may have been formed extraterrestrially in outer space. Complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine, and thymine, have also been formed in the laboratory under conditions mimicking those found in outer space, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar cosmic dust and gas clouds.

Uses in technology

Genetic engineering

Methods have been developed to purify DNA from organisms, such as phenol-chloroform extraction, and to manipulate it in the laboratory, such as restriction digests and the polymerase chain reaction. Modern biology and biochemistry make intensive use of these techniques in recombinant DNA technology. Recombinant DNA is a man-made DNA sequence that has been assembled from other DNA sequences. They can be transformed into organisms in the form of plasmids or in the appropriate format, by using a viral vector. The genetically modified organisms produced can be used to produce products such as recombinant proteins, used in medical research, or be grown in agriculture.

DNA profiling

Forensic scientists can use DNA in blood, semen, skin, saliva or hair found at a crime scene to identify a matching DNA of an individual, such as a perpetrator. This process is formally termed DNA profiling, but may also be called "genetic fingerprinting". In DNA profiling, the lengths of variable sections of repetitive DNA, such as short tandem repeats and minisatellites, are compared between people. This method is usually an extremely reliable technique for identifying a matching DNA. However, identification can be complicated if the scene is contaminated with DNA from several people. DNA profiling was developed in 1984 by British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys, and first used in forensic science to convict Colin Pitchfork in the 1988 Enderby murders case.

The development of forensic science and the ability to now obtain

genetic matching on minute samples of blood, skin, saliva, or hair has

led to re-examining many cases. Evidence can now be uncovered that was

scientifically impossible at the time of the original examination.

Combined with the removal of the double jeopardy

law in some places, this can allow cases to be reopened where prior

trials have failed to produce sufficient evidence to convince a jury.

People charged with serious crimes may be required to provide a sample

of DNA for matching purposes. The most obvious defense to DNA matches

obtained forensically is to claim that cross-contamination of evidence

has occurred. This has resulted in meticulous strict handling procedures

with new cases of serious crime.

DNA profiling is also used successfully to positively identify victims of mass casualty incidents, bodies or body parts in serious accidents, and individual victims in mass war graves, via matching to family members.

DNA profiling is also used in DNA paternity testing

to determine if someone is the biological parent or grandparent of a

child with the probability of parentage is typically 99.99% when the

alleged parent is biologically related to the child. Normal DNA sequencing methods happen after birth, but there are new methods to test paternity while a mother is still pregnant.

DNA enzymes or catalytic DNA

Deoxyribozymes, also called DNAzymes or catalytic DNA, are first discovered in 1994.

They are mostly single stranded DNA sequences isolated from a large

pool of random DNA sequences through a combinatorial approach called in vitro selection or systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment

(SELEX). DNAzymes catalyze variety of chemical reactions including

RNA-DNA cleavage, RNA-DNA ligation, amino acids

phosphorylation-dephosphorylation, carbon-carbon bond formation, and

etc. DNAzymes can enhance catalytic rate of chemical reactions up to

100,000,000,000-fold over the uncatalyzed reaction.

The most extensively studied class of DNAzymes is RNA-cleaving types

which have been used to detect different metal ions and designing

therapeutic agents. Several metal-specific DNAzymes have been reported

including the GR-5 DNAzyme (lead-specific), the CA1-3 DNAzymes (copper-specific), the 39E DNAzyme (uranyl-specific) and the NaA43 DNAzyme (sodium-specific).

The NaA43 DNAzyme, which is reported to be more than 10,000-fold

selective for sodium over other metal ions, was used to make a real-time

sodium sensor in living cells.

Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics involves the development of techniques to store, data mine, search and manipulate biological data, including DNA nucleic acid sequence data. These have led to widely applied advances in computer science, especially string searching algorithms, machine learning, and database theory.

String searching or matching algorithms, which find an occurrence of a

sequence of letters inside a larger sequence of letters, were developed

to search for specific sequences of nucleotides. The DNA sequence may be aligned with other DNA sequences to identify homologous sequences and locate the specific mutations that make them distinct. These techniques, especially multiple sequence alignment, are used in studying phylogenetic relationships and protein function. Data sets representing entire genomes' worth of DNA sequences, such as those produced by the Human Genome Project,

are difficult to use without the annotations that identify the

locations of genes and regulatory elements on each chromosome. Regions

of DNA sequence that have the characteristic patterns associated with

protein- or RNA-coding genes can be identified by gene finding algorithms, which allow researchers to predict the presence of particular gene products and their possible functions in an organism even before they have been isolated experimentally.

Entire genomes may also be compared, which can shed light on the

evolutionary history of particular organism and permit the examination

of complex evolutionary events.

DNA nanotechnology

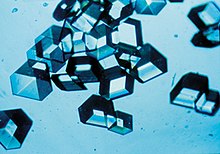

The DNA structure at left (schematic shown) will self-assemble into the structure visualized by atomic force microscopy at right. DNA nanotechnology is the field that seeks to design nanoscale structures using the molecular recognition properties of DNA molecules. Image from Strong, 2004.

DNA nanotechnology uses the unique molecular recognition properties of DNA and other nucleic acids to create self-assembling branched DNA complexes with useful properties.

DNA is thus used as a structural material rather than as a carrier of

biological information. This has led to the creation of two-dimensional

periodic lattices (both tile-based and using the DNA origami method) and three-dimensional structures in the shapes of polyhedra. Nanomechanical devices and algorithmic self-assembly have also been demonstrated, and these DNA structures have been used to template the arrangement of other molecules such as gold nanoparticles and streptavidin proteins.

History and anthropology

Because DNA collects mutations over time, which are then inherited,

it contains historical information, and, by comparing DNA sequences,

geneticists can infer the evolutionary history of organisms, their phylogeny. This field of phylogenetics is a powerful tool in evolutionary biology. If DNA sequences within a species are compared, population geneticists can learn the history of particular populations. This can be used in studies ranging from ecological genetics to anthropology.

Information storage

In a paper published in Nature in January 2013, scientists from the European Bioinformatics Institute and Agilent Technologies

proposed a mechanism to use DNA's ability to code information as a

means of digital data storage. The group was able to encode 739

kilobytes of data into DNA code, synthesize the actual DNA, then

sequence the DNA and decode the information back to its original form,

with a reported 100% accuracy. The encoded information consisted of text

files and audio files. A prior experiment was published in August 2012.

It was conducted by researchers at Harvard University, where the text of a 54,000-word book was encoded in DNA.

Moreover, in living cells, the storage can be turned active by

enzymes. Light-gated protein domains fused to DNA processing enzymes are

suitable for that task in vitro. Fluorescent exonucleases can transmit the output according to the nucleotide they have read.

History

James Watson and Francis Crick (right), co-originators of the double-helix model, with Maclyn McCarty (left)

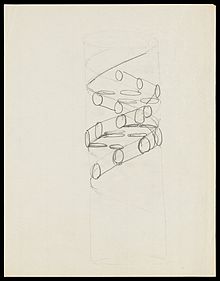

Pencil sketch of the DNA double helix by Francis Crick in 1953

DNA was first isolated by the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher

who, in 1869, discovered a microscopic substance in the pus of

discarded surgical bandages. As it resided in the nuclei of cells, he

called it "nuclein". In 1878, Albrecht Kossel isolated the non-protein component of "nuclein", nucleic acid, and later isolated its five primary nucleobases.

In 1909, Phoebus Levene identified the base, sugar, and phosphate nucleotide unit of the RNA (then named "yeast nucleic acid"). In 1929, Levene identified deoxyribose sugar in "thymus nucleic acid" (DNA).

Levene suggested that DNA consisted of a string of four nucleotide

units linked together through the phosphate groups ("tetranucleotide

hypothesis"). Levene thought the chain was short and the bases repeated

in a fixed order.

In 1927, Nikolai Koltsov

proposed that inherited traits would be inherited via a "giant

hereditary molecule" made up of "two mirror strands that would replicate

in a semi-conservative fashion using each strand as a template". In 1928, Frederick Griffith in his experiment discovered that traits of the "smooth" form of Pneumococcus could be transferred to the "rough" form of the same bacteria by mixing killed "smooth" bacteria with the live "rough" form. This system provided the first clear suggestion that DNA carries genetic information.

In 1933, while studying virgin sea urchin eggs, Jean Brachet suggested that DNA is found in the cell nucleus and that RNA is present exclusively in the cytoplasm.

At the time, "yeast nucleic acid" (RNA) was thought to occur only in

plants, while "thymus nucleic acid" (DNA) only in animals. The latter

was thought to be a tetramer, with the function of buffering cellular

pH.

In 1937, William Astbury produced the first X-ray diffraction patterns that showed that DNA had a regular structure.

In 1943, Oswald Avery, along with coworkers Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty, identified DNA as the transforming principle, supporting Griffith's suggestion (Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment). DNA's role in heredity was confirmed in 1952 when Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase in the Hershey–Chase experiment showed that DNA is the genetic material of the T2 phage.

A blue plaque outside The Eagle pub commemorating Crick and Watson

Late in 1951, Francis Crick started working with James Watson at the Cavendish Laboratory within the University of Cambridge. In 1953, Watson and Crick suggested what is now accepted as the first correct double-helix model of DNA structure in the journal Nature. Their double-helix, molecular model of DNA was then based on one X-ray diffraction image (labeled as "Photo 51") taken by Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling in May 1952, and the information that the DNA bases are paired. On 28 February 1953 Crick interrupted patrons' lunchtime at The Eagle pub in Cambridge to announce that he and Watson had "discovered the secret of life".

Months earlier, in February 1953, Linus Pauling and Robert Corey

proposed a model for nucleic acids containing three intertwined chains,

with the phosphates near the axis, and the bases on the outside. Experimental evidence supporting the Watson and Crick model was published in a series of five articles in the same issue of Nature.

Of these, Franklin and Gosling's paper was the first publication of

their own X-ray diffraction data and original analysis method that

partly supported the Watson and Crick model; this issue also contained an article on DNA structure by Maurice Wilkins and two of his colleagues, whose analysis and in vivo B-DNA X-ray patterns also supported the presence in vivo

of the double-helical DNA configurations as proposed by Crick and

Watson for their double-helix molecular model of DNA in the prior two

pages of Nature. In 1962, after Franklin's death, Watson, Crick, and Wilkins jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Nobel Prizes are awarded only to living recipients. A debate continues about who should receive credit for the discovery.

In an influential presentation in 1957, Crick laid out the central dogma of molecular biology, which foretold the relationship between DNA, RNA, and proteins, and articulated the "adaptor hypothesis". Final confirmation of the replication mechanism that was implied by the double-helical structure followed in 1958 through the Meselson–Stahl experiment.

Further work by Crick and coworkers showed that the genetic code was

based on non-overlapping triplets of bases, called codons, allowing Har Gobind Khorana, Robert W. Holley, and Marshall Warren Nirenberg to decipher the genetic code. These findings represent the birth of molecular biology.