| Maoism | |

| Traditional Chinese | 毛澤東思想 |

|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 毛泽东思想 |

| Literal meaning | "Mao Zedong Thought" |

Maoism is a communist political theory derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong, whose followers are known as Maoists. Developed from the 1950s until the Deng Xiaoping reforms in the 1970s, it was widely applied as the guiding political and military ideology of the Communist Party of China and as theory guiding revolutionary movements around the world. A key difference between Maoism and other forms of Marxism–Leninism is that peasants should be the bulwark of the revolutionary energy, led by the working class in China.

Origins

Strategic Issues of Anti-Japanese Guerrilla War (1938)

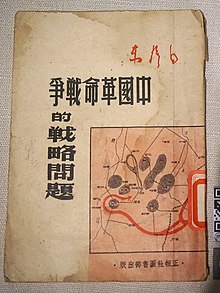

Strategic Issues in the Chinese Revolutionary War (1947)

Modern Chinese intellectual tradition

The modern Chinese intellectual tradition of the turn of the 20th century is defined by two central concepts, namely iconoclasm and nationalism.

Iconoclastic revolution and anti-Confucianism

By

the turn of the 20th century, a proportionately small yet socially

significant cross-section of China's traditional elite (i.e. landlords

and bureaucrats) found themselves increasingly skeptical of the efficacy

and even the moral validity of Confucianism.

These skeptical iconoclasts formed a new segment of Chinese society, a

modern intelligentsia whose arrival—or as historian of China Maurice Meisner would label it, their defection—heralded the beginning of the destruction of the gentry as a social class in China.

The fall of the last imperial Chinese dynasty

in 1911 marked the final failure of the Confucian moral order and it

did much to make Confucianism synonymous with political and social conservatism

in the minds of Chinese intellectuals. It was this association of

conservatism and Confucianism which lent to the iconoclastic nature of

Chinese intellectual thought during the first decades of the 20th

century.

Chinese iconoclasm was expressed most clearly and vociferously by Chen Duxiu during the New Culture Movement which occurred between 1915 and 1919. Proposing the "total destruction of the traditions and values of the past", the New Culture Movement was spearheaded by the New Youth, a periodical which was published by Chen Duxiu and was profoundly influential on the young Mao Zedong, whose first published work appeared on the magazine's pages.

Nationalism and the appeal of Marxism

Along

with iconoclasm, radical anti-imperialism dominated the Chinese

intellectual tradition and slowly evolved into a fierce nationalist

fervor which influenced Mao's philosophy immensely and was crucial in

adapting Marxism to the Chinese model. Vital to understanding Chinese nationalist sentiments of the time is the Treaty of Versailles,

which was signed in 1919. The Treaty aroused a wave of bitter

nationalist resentment in Chinese intellectuals as lands formerly ceded

to Germany in Shandong were—without consultation with the Chinese—transferred to Japanese control rather than returned to Chinese sovereignty.

The negative reaction culminated in the 4 May Incident

in 1919 during which a protest began with 3,000 students in Beijing

displaying their anger at the announcement of the Versailles Treaty's

concessions to Japan. The protest took a violent turn as protesters

began attacking the homes and offices of ministers who were seen as

cooperating with, or being in the direct pay, of the Japanese.[7] The 4 May Incident and Movement which followed "catalyzed the political awakening of a society which had long seemed inert and dormant".

Yet another international event would have a large impact not only on Mao, but also on the Chinese intelligentsia, i.e. the Bolshevik Revolution

of 1917. Although the revolution did elicit interest among Chinese

intellectuals, socialist revolution in China was not considered a viable

option until after the May 4 Incident.

Afterwards, "[t]o become a Marxist was one way for a Chinese

intellectual to reject both the traditions of the Chinese past and

Western domination of the Chinese present".

Yan'an period between November 1935 and March 1947

During the period immediately following the Long March, Mao and the Communist Party of China (CPC) were headquartered in Yan'an, which is a prefecture-level city in Shaanxi

province. During this period, Mao clearly established himself as a

Marxist theoretician and he produced the bulk of the works which would

later be canonized into the "thought of Mao Zedong".

The rudimentary philosophical base of Chinese Communist ideology is

laid down in Mao's numerous dialectical treatises and it was conveyed to

newly recruited party members. This period truly established

ideological independence from Moscow for Mao and the CPC.

Although the Yan'an period did answer some of the questions, both

ideological and theoretical, which were raised by the Chinese Communist

Revolution, it left many of the crucial questions unresolved; including

how the Communist Party of China was supposed to launch a socialist

revolution while completely separated from the urban sphere.

Mao Zedong's intellectual Marxist development

Mao's

Intellectual Marxist development can be divided into five major

periods: (1) the initial Marxist period from 1920–1926; (2) the

formative Maoist period from 1927–1935; (3) the mature Maoist period

from 1935–1940; (4) the Civil-War period from 1940–1949; and (5) the

post-1949 period following the revolutionary victory.

- The initial Marxist period from 1920–1926: Marxist thinking employs imminent socioeconomic explanations and Mao's reasons were declarations of his enthusiasm. Mao did not believe that education alone would bring about the transition from capitalism to communism because of three main reasons. (1) Psychologically: the capitalists would not repent and turn towards communism on their own; (2) the rulers must be overthrown by the people; (3) "the proletarians are discontented, and a demand for communism has arisen and had already become a fact". These reasons do not provide socioeconomic explanations, which usually form the core of Marxist ideology.

- The formative Maoist period from 1927–1935: in this period, Mao avoided all theoretical implications in his literature and employed a minimum of Marxist category thought. His writings in this period failed to elaborate what he meant by the "Marxist method of political and class analysis". Prior to this period, Mao was concerned with the dichotomy between knowledge and action. He was more concerned with the dichotomy between revolutionary ideology and counter-revolutionary objective conditions. There was more correlation drawn between China and the Soviet model.

- The mature Maoist period from 1935–1940: intellectually, this was Mao's most fruitful time. The shift of orientation was apparent in his pamphlet Strategic Problems of China's Revolutionary War (December, 1936). "This pamphlet tried to provide a theoretical veneer for his concern with revolutionary practice". Mao started to separate from the Soviet model since it was not automatically applicable to China. China's unique set of historical circumstances demanded a correspondingly unique application of Marxist theory, an application that would have to diverge from the Soviet approach.

- The Civil-War period from 1940–1949: unlike the Mature period, this period was intellectually barren. Mao focused more on revolutionary practice and paid less attention to Marxist theory. "He continued to emphasize theory as practice-oriented knowledge". The biggest topic of theory he delved into was in connection with the Cheng Feng movement of 1942. It was here that Mao summarized the correlation between Marxist theory and Chinese practice; "The target is the Chinese revolution, the arrow is Marxism–Leninism. We Chinese communists seek this arrow for no other purpose than to hit the target of the Chinese revolution and the revolution of the east". The only new emphasis was Mao's concern with two types of subjectivist deviation: (1) dogmatism, the excessive reliance upon abstract theory; (2) empiricism, excessive dependence on experience.

- The post-1949 period following the revolutionary victory: the victory of 1949 was to Mao a confirmation of theory and practice. "Optimism is the keynote to Mao's intellectual orientation in the post-1949 period". Mao assertively revised theory to relate it to the new practice of socialist construction. These revisions are apparent in the 1951 version of On Contradiction. "In the 1930s, when Mao talked about contradiction, he meant the contradiction between subjective thought and objective reality. In Dialectal Materialism of 1940, he saw idealism and materialism as two possible correlations between subjective thought and objective reality. In the 1940s, he introduced no new elements into his understanding of the subject-object contradiction. In the 1951 version of On Contradiction, he saw contradiction as a universal principle underlying all processes of development, yet with each contradiction possessed of its own particularity".

Components

New Democracy

The theory of the New Democracy

was known to the Chinese revolutionaries from the late 1940s. This

thesis held that for the majority of the people of the planet, the long

road to socialism could only be opened by a "national, popular, democratic, anti-feudal and anti-imperialist revolution, run by the communists".

People's war

Holding that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun",

Maoism emphasizes the "revolutionary struggle of the vast majority of

people against the exploiting classes and their state structures", which

Mao termed a "people's war". Mobilizing large parts of rural populations to revolt against established institutions by engaging in guerrilla warfare, Maoist Thought focuses on "surrounding the cities from the countryside".

Maoism views the industrial-rural divide as a major division

exploited by capitalism, identifying capitalism as involving industrial

urban developed First World societies ruling over rural developing Third World societies.

Maoism identifies peasant insurgencies in particular national contexts

were part of a context of world revolution, in which Maoism views the

global countryside would overwhelm the global cities. Due to this imperialism by the capitalist urban First World towards the rural Third World, Maoism has endorsed national liberation movements in the Third World.

Mass line

Contrary to the Leninist vanguard model employed by the Bolsheviks, the theory of the mass line

holds that party must not be separate from the popular masses, either

in policy or in revolutionary struggle. To conduct a successful

revolution the needs and demands of the masses must be told to the party

so that the party can interpret them with a Marxist view.

Cultural Revolution

The theory of the Cultural Revolution

states that the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the

proletariat does not wipe out bourgeois ideology—the class-struggle

continues and even intensifies during socialism, therefore a constant

struggle against these ideologies and their social roots must be

conducted. Cultural Revolution is directed also against traditionalism.

Contradiction

Mao drew from the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin in elaborating his theory. Philosophically, his most important reflections emerge on the concept of "contradiction" (maodun). In two major essays, On Contradiction and On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, he adopts the positivist-empiricist

idea (shared by Engels) that contradiction is present in matter itself

and thus also in the ideas of the brain. Matter always develops through a

dialectical contradiction: "The interdependence of the contradictory

aspects present in all things and the struggle between these aspects

determine the life of things and push their development forward. There

is nothing that does not contain contradiction; without contradiction

nothing would exist".

Furthermore, each contradiction (including class struggle,

the contradiction holding between relations of production and the

concrete development of forces of production) expresses itself in a

series of other contradictions, some dominant, others not. "There are

many contradictions in the process of development of a complex thing,

and one of them is necessarily the principal contradiction whose

existence and development determine or influence the existence and

development of the other contradictions".

Thus, the principal contradiction should be tackled with priority

when trying to make the basic contradiction "solidify". Mao elaborates

further on this theme in the essay On Practice, "on the relation between knowledge and practice, between knowing and doing". Here, Practice

connects "contradiction" with "class struggle" in the following way,

claiming that inside a mode of production there are three realms where

practice functions: economic production, scientific experimentation

(which also takes place in economic production and should not be

radically disconnected from the former) and finally class struggle.

These may be considered the proper objects of economy, scientific

knowledge and politics.

These three spheres deal with matter in its various forms,

socially mediated. As a result, they are the only realms where knowledge

may arise (since truth and knowledge only make sense in relation to

matter, according to Marxist epistemology). Mao emphasizes—like Marx in

trying to confront the "bourgeois idealism" of his time—that knowledge

must be based on empirical evidence.

Knowledge results from hypotheses verified in the contrast with a

real object; this real object, despite being mediated by the subject's

theoretical frame, retains its materiality and will offer resistance to

those ideas that do not conform to its truth. Thus in each of these

realms (economic, scientific and political practice), contradictions

(principle and secondary) must be identified, explored and put to

function to achieve the communist goal. This involves the need to know,

"scientifically", how the masses produce (how they live, think and

work), to obtain knowledge of how class struggle (the main contradiction

that articulates a mode of production, in its various realms) expresses

itself.

Mao held that contradictions were the most important feature of

society and since society is dominated by a wide range of

contradictions, this calls for a wide range of varying strategies.

Revolution is necessary to fully resolve antagonistic contradictions

such as those between labour and capital. Contradictions arising within

the revolutionary movement call for ideological correction to prevent

them from becoming antagonistic.

Maoism is described as being Marxism–Leninism adapted to Chinese conditions whereas its variant Marxism–Leninism–Maoism is considerated universally applicable

Three Worlds Theory

Three Worlds Theory states that during the Cold War two imperialist states formed the "first world"—the United States and the Soviet Union.

The second world consisted of the other imperialist states in their

spheres of influence. The third world consisted of the non-imperialist

countries. Both the first and the second world exploit the third world,

but the first world is the most aggressive party. The workers in the

first and second world are "bought up" by imperialism, preventing

socialist revolution. On the other hand, the people of the third world

have not even a short-sighted interest in the prevailing circumstances,

hence revolution is most likely to appear in third world countries,

which again will weaken imperialism opening up for revolutions in other

countries too.

Agrarian socialism

Maoism

departs from conventional European-inspired Marxism in that its focus

is on the agrarian countryside, rather than the industrial urban

forces—this is known as agrarian socialism.

Notably, Maoist parties in Peru, Nepal and the Philippines have adopted

equal stresses on urban and rural areas, depending on the country's

focus of economic activity. Maoism broke with the state capitalist framework of the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev, dismissing it as revisionist, a pejorative term among communists referring to those who fight for capitalism in the name of socialism and who depart from historical and dialectical materialism.

Although Maoism is critical of urban industrial capitalist powers, it views urban industrialization as a prerequisite to expand economic development

and socialist reorganization to the countryside, with the goal being

the achievement of rural industrialization that would abolish the

distinction between town and countryside.

Maoism in China

In its post-revolutionary period, Mao Zedong Thought is defined in the CPC's Constitution as "Marxism–Leninism applied in a Chinese context", synthesized by Mao and China's "first-generation leaders". It asserts that class struggle continues even if the proletariat has already overthrown the bourgeoisie

and there are capitalist restorationist elements within the Communist

Party itself. Maoism provided the CPC's first comprehensive theoretical

guideline with regards to how to continue socialist revolution, the

creation of a socialist society, socialist military construction and

highlights various contradictions in society to be addressed by what is

termed "socialist construction". While it continues to be lauded to be

the major force that defeated "imperialism and feudalism" and created a

"New China" by the Communist Party of China, the ideology survives only

in name on the Communist Party's Constitution as Deng Xiaoping abolished most Maoist practices in 1978, advancing a guiding ideology called "socialism with Chinese characteristics".

Maoism after Mao

China

Shortly after Mao's death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping initiated socialist market reforms in 1978, thereby beginning the radical change in Mao's ideology in the People's Republic of China (PRC). Although Mao Zedong Thought nominally remains the state ideology, Deng's admonition to "seek truth from facts" means that state policies are judged on their practical consequences and in many areas the role of ideology

in determining policy has thus been considerably reduced. Deng also

separated Mao from Maoism, making it clear that Mao was fallible and

hence the truth of Maoism comes from observing social consequences

rather than by using Mao's quotations as holy writ, as was done in Mao's lifetime.

Contemporary Maoists in China criticize the social inequalities

created by the revisionist Communist Party. Some Maoists say that Deng's

Reform and Opening

economic policies that introduced market principles spelled the end of

Maoism in China, although Deng himself asserted that his reforms were

upholding Mao Zedong Thought in accelerating the output of the country's

productive forces.

In addition, the party constitution has been rewritten to give

the socialist ideas of Deng prominence over those of Mao. One

consequence of this is that groups outside China which describe

themselves as Maoist generally regard China as having repudiated Maoism

and restoring capitalism

and there is a wide perception both inside and outside China that China

has abandoned Maoism. However, while it is now permissible to question

particular actions of Mao and talk about excesses taken in the name of

Maoism, there is a prohibition in China on either publicly questioning

the validity of Maoism or on questioning whether the current actions of

the CPC are "Maoist".

Although Mao Zedong Thought is still listed as one of the Four Cardinal Principles

of the People's Republic of China, its historical role has been

re-assessed. The Communist Party now says that Maoism was necessary to

break China free from its feudal past, but it also says that the actions

of Mao are seen to have led to excesses during the Cultural Revolution.

The official view is that China has now reached an economic and political stage, known as the primary stage of socialism,

in which China faces new and different problems completely unforeseen

by Mao and as such the solutions that Mao advocated are no longer

relevant to China's current conditions. The official proclamation of the

new CPC stance came in June 1981, when the Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh

National Party Congress Central Committee took place. The 35,000-word Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People's Republic of China reads:

Chief responsibility for the grave 'Left' error of the 'cultural revolution,' an error comprehensive in magnitude and protracted in duration, does indeed lie with Comrade Mao Zedong... [and] far from making a correct analysis of many problems, he confused right and wrong and the people with the enemy... herein lies his tragedy.

Scholars outside China see this re-working of the definition of

Maoism as providing an ideological justification for what they see as

the restoration of the essentials of capitalism in China by Deng and his

successors, who sought to "eradicate all ideological and physiological

obstacles to economic reform". In 1978, this led to the Sino-Albanian split when Albanian leader Enver Hoxha denounced Deng as a revisionist and formed Hoxhaism as an anti-revisionist form of Marxism.

Mao himself is officially regarded by the CPC as a "great revolutionary leader" for his role in fighting against the Japanese fascist invasion

during the Second World War and creating the People's Republic of

China, but Maoism as implemented between 1959 and 1976 is regarded by

today's CPC as an economic and political disaster. In Deng's day,

support of radical Maoism was regarded as a form of "left deviationism"

and being based on a cult of personality, although these "errors" are officially attributed to the Gang of Four rather than being attributed to Mao himself. Thousands of Maoists were arrested in the Hua Guofeng period after 1976. The prominent Maoists Zhang Chunqiao and Jiang Qing

were sentenced to death with a two-year-reprieve while some others were

sentenced to life imprisonment or imprisonment for 15 years.

Internationally

After the death of Mao in 1976 and the resulting power-struggles in

China that followed, the international Maoist movement was divided into

three camps. One group, composed of various ideologically nonaligned

groups, gave weak support to the new Chinese leadership under Deng Xiaoping.

Another camp denounced the new leadership as traitors to the cause of

Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought. The third camp sided with the

Albanians in denouncing the Three Worlds Theory of the CPC.

Though initially praising the Soviet Union prior to, during and shortly after the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara later came out in support of Maoism and advocated the adoption of the ideology throughout Latin America. The pro-Albanian camp would start to function as an international group as well (led by Enver Hoxha and the APL) and was also able to amalgamate many of the communist groups in Latin America, including the Communist Party of Brazil and the Marxist–Leninist Communist Party in Ecuador. Later, Latin American Communists such as Peru's Shining Path also embraced the tenets of Maoism.

The new Chinese leadership showed little interest in the various

foreign groups supporting Mao's China. Many of the foreign parties that

were fraternal parties

aligned with the Chinese government before 1975 either disbanded,

abandoned the new Chinese government entirely, or even renounced Marxism–Leninism and developed into non-communist, social democratic

parties. What is today called the international Maoist movement evolved

out of the second camp—the parties that opposed Deng and said they

upheld the true legacy of Mao.

Maoism's international influence

Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) in February 2013

From 1962 onwards, the challenge to the Soviet hegemony in the world communist movement made by the CPC resulted in various divisions in communist parties around the world. At an early stage, the Albanian Party of Labour sided with the CPC. So did many of the mainstream (non-splinter group) Communist parties in South-East Asia, like the Burmese Communist Party, Communist Party of Thailand and Communist Party of Indonesia. Some Asian parties, like the Workers Party of Vietnam and the Workers Party of Korea attempted to take a middle-ground position.

The Khmer Rouge of Cambodia is said to have been a replica of the Maoist regime. According to the BBC, the Communist Party of Kampuchea

(CPK) in Cambodia, better known as the Khmer Rouge, identified strongly

with Maoism and it is generally labeled a Maoist movement today.

However, Maoists and Marxists generally contend that the CPK strongly

deviated from Marxist doctrine and the few references to Maoist China in

CPK propaganda were critical of the Chinese.

Various efforts have sought to regroup the international

communist movement under Maoism since the time of Mao's death in 1976.

In the West and Third World, a plethora of parties and organizations

were formed that upheld links to the CPC. Often they took names such as

Communist Party (Marxist–Leninist) or Revolutionary Communist Party to

distinguish themselves from the traditional pro-Soviet communist

parties. The pro-CPC movements were in many cases based among the wave

of student radicalism that engulfed the world in the 1960s and 1970s.

Only one Western classic communist party sided with the CPC, the Communist Party of New Zealand. Under the leadership of the CPC and Mao Zedong, a parallel international communist movement emerged to rival that of the Soviets, although it was never as formalized and homogeneous as the pro-Soviet tendency.

Another effort at regrouping the international communist movement is the International Conference of Marxist-Leninist Parties and Organizations (ICMLPO). Three notable parties that participate in the ICMLPO are the Marxist–Leninist Party of Germany (MLPD), the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and Marxist–Leninist Communist Organization – Proletarian Way.

The ICMLPO seeks to unity around Marxism-Leninism, not Maoism. However,

some of the parties and organizations within the ICMLPO identify as Mao

Zedong Thought or Maoist.

Afghanistan

The Progressive Youth Organization was a Maoist organization in Afghanistan. It was founded in 1965 with Akram Yari as its first leader, advocating the overthrow of the then-current order by means of people's war.

Bangladesh

Purba Banglar Sarbahara Party is a Maoist party in Bangladesh. It was founded in 1968 with Siraj Sikder as its first leader. The party played a role in the Bangladesh Liberation War.

Belgium

The Sino-Soviet split had an important influence on communism in Belgium. The pro-Soviet Communist Party of Belgium experienced a split of a Maoist wing under Jacques Grippa.

The latter was a lower-ranking CPB member before the split, but Grippa

rose in prominence as he formed a worthy internal Maoist opponent to the

CPB leadership. His followers where sometimes referred to as Grippisten

or Grippistes. When it became clear that the differences between the

pro-Moscow leadership and the pro-Beijing wing were too great, Grippa

and his entourage decided to split from the CPB and formed the Communist Party of Belgium – Marxist–Leninist (PCBML). The PCBML had some influence, mostly in the heavily industrialized Borinage region of Wallonia,

but never managed to gather more support than the CPB. The latter held

most of its leadership and base within the pro-Soviet camp. However, the

PCBML was the first European Maoist party that was officially

recognized as a sister-party of the CPC by Beijing.

Though the PCBML never really gained a foothold in Flanders,

there was a reasonably successful Maoist movement in this region. Out

of the student unions that formed in the wake of the May 1968 protests,

Alle Macht Aan De Arbeiders (AMADA) or All Power To The Workers, was

formed as a vanguard party-under-construction. This Maoist group

originated mostly out of students from the universities of Leuven and Ghent,

but did manage to gain some influence among the striking miners during

the shut-downs of the Belgian stonecoal mines in the late 1960s and

early 1970s. This group became the Workers' Party of Belgium

(WPB) in 1979 and still exists today, although its power base has

shifted somewhat from Flanders towards Wallonia. The WPB stayed loyal to

the teachings of Mao for a long time, but after a general congress held

in 2008 the party formally broke with its Maoist/Stalinist past.

Ecuador

The Communist Party of Ecuador – Red Sun, also known as Puka Inti, is a small Maoist guerrilla organization in Ecuador.

India

Communist Party of India (Maoist)

is the leading Maoist organisation in India. Two major political

groupings owing allegiance to Mao's ideas, the Communist Party of India

(Marxist–Leninist) People's War and the Maoist Communist Centre of India

(MCCI), merged on 21 September 2004 to form Communist Party of India

(Maoist).

Iran

Union of Iranian Communists (Sarbedaran) was an Iran

Maoist organization. UIC (S) was formed in 1976 after the alliance of a

number of Maoist groups carrying out military actions within Iran. In

1982, the UIC (S) mobilized forces in forests around Amol

and launched an insurgency against the Islamist Government. The

uprising was eventually a failure and many UIC (S) leaders were shot.

Palestine

The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine

is a Maoist political and military organization. The DFLP's original

political orientation was based on the view that Palestinian national

goals could be achieved only through revolution of the masses and people's war.

Portugal

The flag of FP-25

Maoist movements in Portugal were very active during the 1970s, especially during the Carnation Revolution that led to the fall of the fascist government the Estado Novo in 1974.

The largest Maoist movement in Portugal was the Portuguese Workers' Communist Party. The party was among the most active resistance movements before the Portuguese democratic revolution of 1974,

especially among students of Lisbon. After the revolution, the MRPP

achieved fame for its large and highly artistic mural paintings.

Intensely active during 1974 and 1975, during that time the party

had members that later came to be very important in national politics.

For example, a future Prime Minister of Portugal, José Manuel Durão Barroso was active within Maoist movements in Portugal and identified as a Maoist. In the 1980s, the Forças Populares 25 de Abril

was another far-left Maoist armed organization operating in Portugal

between 1980 and 1987 with the goal of creating socialism in post-Carnation Revolution Portugal.

Spain

The Communist Party of Spain (Reconstituted) was a Spanish clandestine Maoist party. The armed wing of the party was First of October Anti-Fascist Resistance Groups.

Turkey

Communist Party of Turkey/Marxist–Leninist (TKP/ML) is a Maoist organization in Turkey currently waging a people's war against the Turkish government. It was founded in 1972 with İbrahim Kaypakkaya as its first leader. The armed wing of the party is named the Workers' and Peasants' Liberation Army in Turkey (TIKKO).

United States

In the United States during the late 1960s, parts of the emerging New Left rejected the Marxism espoused by the Soviet Union and instead adopted pro-Chinese communism.

The Black Panther Party, especially under the leadership of Huey Newton,

was influenced by Mao Zedong's ideas. Into the 1970s, Maoists in the

United States, e.g. Maoist representative Jon Lux, formed a large part

of the New Communist movement.

The Revolutionary Communist Party, USA is also a Maoist movement.

Criticisms and interpretations

Despite falling out of favor within the Communist Party of China by 1978, Mao is still revered, with Deng's famous "70% right, 30% wrong" line

Maoism has fallen out of favour within the Communist Party of China,

beginning with Deng Xiaoping's reforms in 1978. Deng believed that

Maoism showed the dangers of "ultra-leftism", manifested in the harm

perpetrated by the various mass movements that characterized the Maoist

era. In Chinese communism, the term "left" can be taken as a euphemism

for Maoist policies. However, Deng stated that the revolutionary side of

Maoism should be considered separate from the governance side, leading

to his famous epithet that Mao was "70% right, 30% wrong".

Chinese scholars generally agree that Deng's interpretation of Maoism

preserves the legitimacy of Communist rule in China, but at the same

time criticizes Mao's brand of economic and political governance.

Critic Graham Young says that Maoists see Joseph Stalin

as the last true socialist leader of the Soviet Union, but allows that

the Maoist assessments of Stalin vary between the extremely positive and

the more ambivalent. Some political philosophers, such as Martin Cohen, have seen in Maoism an attempt to combine Confucianism and socialism—what one such called "a third way between communism and capitalism".

Enver Hoxha

critiqued Maoism from a Marxist–Leninist perspective, arguing that New

Democracy halts class struggle, the theory of the three worlds is

"counter-revolutionary" and questioned Mao's guerilla warfare methods.

Some say Mao departed from Leninism not only in his near-total

lack of interest in the urban working class, but also in his concept of

the nature and role of the party. For Lenin, the party was sacrosanct

because it was the incarnation of the "proletarian consciousness" and

there was no question about who were the teachers and who were the

pupils. On the other hand, for Mao this question would always be

virtually impossible to answer.

The implementation of Maoist thought in China was arguably responsible for as many as 70 million deaths during peacetime, with the Cultural Revolution, Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957–1958 and the Great Leap Forward. Some historians have argued that because of Mao's land reforms during the Great Leap Forward which resulted in famines,

thirty million perished between 1958 and 1961. By the end of 1961, the

birth rate was nearly cut in half because of malnutrition.

Active campaigns, including party purges and "reeducation" resulted in

imprisonment and/or the execution of those deemed contrary to the

implementation of Maoist ideals.

The incidents of destruction of cultural heritage, religion and art

remain controversial. Some Western scholars saw Maoism specifically

engaged in a battle to dominate and subdue nature and was a catastrophe

for the environment.

Populism

Mao

also believed strongly in the concept of a unified people. These notions

were what prompted him to investigate the peasant uprisings in Hunan

while the rest of China's communists were in the cities and focused on

the orthodox Marxist proletariat.

Many of the pillars of Maoism such as the distrust of intellectuals and

the abhorrence of occupational specialty are typical populist ideas. The concept of "people's war"

which is so central to Maoist thought is directly populist in its

origins. Mao believed that intellectuals and party cadres had to become

first students of the masses to become teachers of the masses later.

This concept was vital to the strategy of the aforementioned "people's

war".

Nationalism

Mao's

nationalist impulses also played a crucially important role in the

adaption of Marxism to the Chinese model and in the formation of Maoism.

Mao truly believed that China was to play a crucial preliminary role in

the socialist revolution internationally. This belief, or the fervor

with which Mao held it, separated Mao from the other Chinese communists

and led Mao onto the path of what Leon Trotsky called "Messianic

Revolutionary Nationalism", which was central to his personal

philosophy. German post–World War II Strasserist Michael Kühnen, himself a former Maoist, once praised Maoism as being a Chinese form of national socialism.

Mao-Spontex

Mao-Spontex

refers to a Maoist interpretation in western Europe which stresses the

importance of the cultural revolution and overthrowing hierarchy.