Ashley Montagu

| |

|---|---|

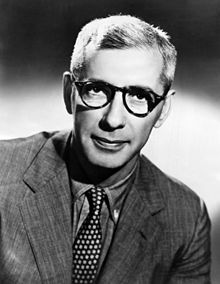

Ashley Montagu in 1958

| |

| Born | 28 June 1905 |

| Died | 26 November 1999 (aged 94)

Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | American |

| Known for | Popularizing the term "ethnic group" |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropology |

Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu (June 28, 1905 – November 26, 1999), previously known as Israel Ehrenberg, was a British-American anthropologist who popularized the study of topics such as race and gender and their relation to politics and development. He was the rapporteur, in 1950, for the UNESCO statement "The Race Question". As a young man he changed his name from Ehrenberg to "Montague Francis Ashley-Montagu". After relocating to the United States he used the name "Ashley Montagu". Montagu, who became a naturalized American citizen in 1940, taught and lectured at Harvard, Princeton, Rutgers, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and New York University. Forced out of his Rutgers position after the McCarthy hearings, he repositioned himself as a public intellectual in the 1950s and 1960s, appearing regularly on television shows and writing for magazines and newspapers. He authored over sixty books throughout this lifetime. In 1995, the American Humanist Association named him the Humanist of the Year.

Early life and education

Montagu began life as Israel Ehrenberg, having been born on June 28, 1905, in London, England. He grew up in London's East End. He remembered often being subjected to antisemitic abuse when he ventured out of his own Jewish neighborhood. Montagu attended the Central Foundation Boys' School. He developed an interest in anatomy very early and as a boy was befriended by Scottish anatomist and anthropologist Arthur Keith under whom he studied informally.

In 1922, at the age of 17, he entered University College London, where he received a diploma in psychology after studying with Karl Pearson and Charles Spearman and taking anthropology courses with Grafton Elliot Smith and Charles Gabriel Seligman. He also studied at the London School of Economics, where he became one of the first students of Bronisław Malinowski. In 1931, he emigrated to the United States. At this time, he wrote a letter introducing himself to Harvard anthropologist Earnest Hooton,

claiming to having been "educated at Cambridge, Oxford, London,

Florence, and Columbia" and having earned M.A. and PhD degrees. In reality, Montagu had not graduated from Cambridge or Oxford and did not yet have a PhD. He taught anatomy to dental students in the United States, and received his doctorate in 1936, when he produced a dissertation at Columbia University, Coming into being among the Australian Aborigines: A study of the procreative beliefs of the native tribes of Australia which was supervised by cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict. He became a professor of anthropology at Rutgers University, working there from 1949 until 1955.

Career

During the 1940s, Montagu published a series of works questioning the validity of race as a biological concept, including the UNESCO "Statement on Race", and his very well known Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: the Fallacy of Race. He was particularly opposed to the work of Carleton S. Coon, and the term "race". In 1952, together with William Vogt, he gave the first Alfred Korzybski Memorial Lecture, inaugurating the series.

Montagu wrote the Foreword and Bibliography of the 1955 edition of Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution by Petr Kropotkin, which was reprinted in 2005.

Due to disputes concerning his involvement with the UNESCO "Statement on Race", Montagu became a target for anti-communists, and, untenured, was dismissed from Rutgers University and "found all other academic avenues blocked." He retired from his academic career in 1955 and moved to Princeton, New Jersey to continue his popular writing and public appearances. He became a well-known guest of Johnny Carson's The Tonight Show.

He addressed his numerous published studies of the significant

relationship of mother and infant to the general public. The humanizing

effects of touch informed the studies of isolation-reared monkeys and

adult pathological violence that is the subject of his Time-Life

documentary Rock A Bye Baby (1970).

Later in life, Montagu actively opposed genital modification and mutilation of children. In 1994, James Prescott wrote the Ashley Montagu Resolution to End the Genital Mutilation of Children Worldwide: a Petition to the World Court, The Hague, named in honor of Montagu, who was one of its original signers.

Montagu was a noted critic of creationism. He edited Science and Creationism, a volume which refuted creationist arguments.

A posthumous biography of Montagu, Love Forms the Bones, was written by anthropologist Susan Sperling and published in 2005.

Work

Statement on Race

Ashley Montagu wrote a book titled Statement on Race.

In this book, Montagu explains every statement in extreme detail, even

though Ashley Montagu only majorly participated in writing the first two

UNESCO Statements. Montagu was one of the ten scientists invited to

serve on a committee which later came to be known as the Committee of

Experts on Race Problems. The main purpose of the organization was to contribute peace and security to others by using science and culture.

The UNESCO Statements were developed to help others realize that humans

are all one species and "race" is not a valid biological concept.

The first statement says, "Scientists have reached general

agreement in recognizing that mankind is one: that all men belong to the

same species, Homo sapiens."

The first statement was put in such a way that laymen would be able to

understand a scientist's point of view. They worded it so that people

who were not knowledgeable about the subject would understand. "Homo

sapiens is made up of a number of populations, each one of which differs

from the others." That states that even though there is variability in

the individual's genetic heritage, all belong to a discrete species and

should be treated equally.

The second statement says that since human history is widely

diverse and complex, there are many human populations that cannot be

easily classified “racially”. However, some anthropologists believe that mankind is classified into at least three major human races.

Even though it is believed that there are many human races, it gives no

support that there is one race that is superior or inferior to any of

the other races.

The third statement gives views on the biological aspect of the race question. It explains that different human groups diverged from a common stock and that is the reason for their biological differences. The third statement also goes into detail about human evolution and how important it is for H. sapiens to survive and grow.

The fourth statement says, "All men are born free and equal both in dignity and in rights."

The fourth statement says that racism stultifies development and

threatens world peace. "The division of human species into 'races' is

partly conventional and partly arbitrary and does not imply any

hierarchy whatsoever."

The UNESCO Statements were made to address the race question and

to help provide clarity from a scientist's perspective. Even though

Montagu did not contribute to writing all of the UNESCO Statements, his

contribution helped to clarify the question against race.

Man's Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race

One of his works, Man's Most Dangerous Myth,

was written in 1942, when race was considered the determinant of

people's character and intelligence. Montagu presented a unique theory

for his time: "in biology race is defined as a subdivision of species

which inherits physical characteristics distinguishing it from other

populations of the species. In this sense there are many human 'races.'

But this is not the sense in which many anthropologists,

race-classifiers, and racists have used the term." He admits that in a

biological sense, there is the existence of races within mankind.

However, he also believes that not all of mankind can be classified.

Part of his reasoning has to do with mixed origin, which has resulted in

“overlapping” of physicalities. Instead of races and subspecies, he

prefers mixed ethnic groups.

His writing further emphasizes the complexity of our descent and

rejects claims that support one race being superior when compared to

others. He also says profoundly that the "so-called" main divisions of

mankind are species instead of races.

He says this idea or concept of race originated around the 18th

century. The concept developing as a direct result of slavery and the

slave trade. As a side effect of slavery, naturally, humanity has

divided racism, this has carried and proceeded to dominate culture. The

physical difference furthered the establishment of races and evident

differences between individuals. He mentions Darwin and other

forefathers who touched on this topic while they attempted to explain

race to all. He touches on society, genetics, psychological, culture,

war, democracy, eugenics, and social factors as contributors that

enhance this idea of race.

Man's Most Dangerous Myth was revised into new editions

six times by Montagu, the last in 1997 when he was 92 years old, and is

still in print over 75 years after its initial publication.

The Natural Superiority of Women

Originally produced as a magazine article, The Natural Superiority of Women,

published in 1952, was one of the major documents of second wave

feminism and the only one written by a man. Using his background as a

physical anthropologist, Montagu points to the biological advantages

that the women of the human species have for long term survival. The

book was revised five times, the last edition published shortly before

his death in 1999 and still in print.

The Elephant Man

Possibly

one of Montagu's least significant works was the most famous one. His

biography of a deformed 19th century British man, Joseph Merrick, dubbed The Elephant Man, was published in 1971 and formed the basis of the 1980 movie directed by David Lynch.

Legacy

An Ashley Montagu Fellowship for the Public Understanding of Human Sciences has been established at the University of Sydney, in Australia, and is currently held by anthropologist Dr Stephen Juan.

In popular culture

- Montagu is the writer and director of the film One World or None. Produced in 1946 by The National Committee on Atomic Information, this short documentary exposes the dangers of nuclear weapons and argues that only international cooperation and proper control of atomic energy can avoid war and guarantee the use of this force for the benefit of mankind.

- Footage of Ashley Montagu talking with Charlton Heston about his character in the movie appears as a bonus in the special DVD edition of The Omega Man.

- Archive footage of him, among others (including Carl Sagan), is featured in The X-Files episode "Gethsemane."

- The saying "International law exists only in textbooks on international law," which is often attributed to Albert Einstein, was in fact said to Einstein by Montagu.

Selected bibliography

- Coming Into Being Among the Australian Aborigines, New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1938.

- Man's Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, New York: Harper, 1942.

- On Being Human, New York: H. Schuman, 1950.

- The Natural Superiority of Women. Macmillan. 1953.

- The Direction of Human Development: Biological and Social Bases, New York: Harper, 1955.

- Toynbee and History: Critical Essays and Reviews (editor) (1956 ed.). Boston: Extending Horizons Books. ISBN 0-87558-026-2.. A critique of Arnold J. Toynbee's seminal A Study of History.

- Anthropology and Human Nature, Boston: P. Sargent, 1957.

- Man: His First Million Years, Cleveland: World Pub. Co., 1957.[10]

- The Cultured Man, Cleveland: World Pub. Co., 1958.

- Human Heredity, Cleveland: World Pub. Co, 1959.

- Life Before Birth, New York: New American Library, 1964.

- The Concept of Race (editor), New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1964.

- Man's Evolution: An Introduction to Physical Anthropology, (co-authored with C. Loring Brace), New York: Macmillan, 1965. Second edition published as Human Evolution: An Introduction to Biological Anthropology, New York: Macmillan, 1977, ISBN 0-02313-190-X.

- The Anatomy of Swearing, New York: Macmillan, 1967.

- Man and Aggression, New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin. Harper & Row. 1978. ISBN 978-0-06-012979-8.

- The Elephant Man: A Study in Human Dignity, New York: Outerbridge and Dienstfrey, 1971.

- Culture and Human Development, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974, ISBN 0-13195-578-0.

- Race and IQ (editor), New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

- The Nature of Human Aggression, New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Learning Non-Aggression: The Experience of Non-Literate Societies (editor), New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-19502-342-0

- The Human Connection (co-authored with Floyd W. Matson), New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979, ISBN 0-07042-840-9.

- Growing Young, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981. Second edition, Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey, 1989, ISBN 0-89789-166-X

- Science and Creationism (co-edited with Isaac Asimov), Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-195-03252-7. Features the writing of Roger Lewin, Kenneth R. Miller, Robert Root-Bernstein, George M. Marsden, Stephen Jay Gould, Gunther S. Stent, Kenneth E. Boulding, Garrett Hardin, Laurie R. Godfrey, Isaac Asimov, Sidney W. Fox, L. Beverly Halstead, Roger J. Cuffey, Roy A. Gallant, Robert M. May, Michael Ruse, WIlliam R. Overton, and Sidney Ratner.

- Living and Loving (edited with notes by Tsuyoshi Amemiya and Kazuo Takeno), Tokyo: Kinseido, 1986, ISBN 4-76470-470-6.

- The Peace of The World, Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1987, ISBN 4-32742-050-6.

- The Dehumanization of Man (co-author with Floyd Matson), New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

- Nude and Natural, 12 (1), The Naturists, 1992

- Man's Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, 6th edition. Walnut Creek CA: AltaMira Press, 1997

- The Natural Superiority of Women, 5th edition. Walnut Creek CA: AltaMira Press. 1999.