From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Endless knot on Nepalese temple prayer wheel

Karma

symbols such as endless knot (above) are common cultural motifs in

Asia. Endless knots symbolize interlinking of cause and effect, a Karmic

cycle that continues eternally. The endless knot is visible in the

center of the

prayer wheel.

Karma (; Sanskrit: कर्म, romanized: karma, IPA: [ˈkɐɽmɐ] ( listen); Pali: kamma) means action, work or deed;

it also refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where

intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that

individual (effect).

Good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and happier

rebirths, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and bad

rebirths.

listen); Pali: kamma) means action, work or deed;

it also refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where

intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that

individual (effect).

Good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and happier

rebirths, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and bad

rebirths.

The philosophy of karma is closely associated with the idea of rebirth in many schools of Indian religions (particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism) as well as Taoism.

In these schools, karma in the present affects one's future in the

current life, as well as the nature and quality of future lives – one's saṃsāra.

Definition

Karma as action and reaction: if we show goodness, we will reap goodness.

Karma is the executed "deed", "work", "action", or "act", and it is also the "object", the "intent". Wilhelm Halbfass explains karma (karman) by contrasting it with another Sanskrit word kriya. The word kriya is the activity along with the steps and effort in action, while karma

is (1) the executed action as a consequence of that activity, as well

as (2) the intention of the actor behind an executed action or a planned

action (described by some scholars

as metaphysical residue left in the actor). A good action creates good

karma, as does good intent. A bad action creates bad karma, as does bad

intent.

Karma also refers to a conceptual principle that originated in

India, often descriptively called the principle of karma, sometimes as

the karma theory or the law of karma. In the context of theory, karma is complex and difficult to define. Different schools of Indologists

derive different definitions for the karma concept from ancient Indian

texts; their definition is some combination of (1) causality that may be

ethical or non-ethical; (2) ethicization, that is good or bad actions

have consequences; and (3) rebirth.

Other Indologists include in the definition of karma theory that which

explains the present circumstances of an individual with reference to

his or her actions in past. These actions may be those in a person's

current life, or, in some schools of Indian traditions, possibly actions

in their past lives; furthermore, the consequences may result in

current life, or a person's future lives. The law of karma operates independent of any deity or any process of divine judgment.

Difficulty in arriving at a definition of karma arises because of

the diversity of views among the schools of Hinduism; some, for

example, consider karma and rebirth linked and simultaneously essential,

some consider karma but not rebirth essential, and a few discuss and

conclude karma and rebirth to be flawed fiction. Buddhism and Jainism have their own karma precepts. Thus karma has not one, but multiple definitions and different meanings.

It is a concept whose meaning, importance and scope varies between

Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and other traditions that originated in

India, and various schools in each of these traditions. O'Flaherty

claims that, furthermore, there is an ongoing debate regarding whether

karma is a theory, a model, a paradigm, a metaphor, or a metaphysical

stance.

Karma theory as a concept, across different Indian religious

traditions, shares certain common themes: causality, ethicization and

rebirth.

Causality

Lotus

symbolically represents karma in many Asian traditions. A blooming

lotus flower is one of the few flowers that simultaneously carries seeds

inside itself while it blooms. Seed is symbolically seen as cause, the

flower effect. Lotus is also considered as a reminder that one can grow,

share good karma and remain unstained even in muddy circumstances.

A common theme to theories of karma is its principle of causality.

One of the earliest association of karma to causality occurs in the

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad of Hinduism. For example, at 4.4.5–6, it

states:

Now as a man is like this or like that,

according as he acts and according as he behaves, so will he be;

a man of good acts will become good, a man of bad acts, bad;

he becomes pure by pure deeds, bad by bad deeds;

And here they say that a person consists of desires,

and as is his desire, so is his will;

and as is his will, so is his deed;

and whatever deed he does, that he will reap.

The relationship of karma to causality is a central motif in all schools of Hindu, Jain and Buddhist thought.

The theory of karma as causality holds that (1) executed actions of an

individual affects the individual and the life he or she lives, and (2)

the intentions of an individual affects the individual and the life he

or she lives. Disinterested actions, or unintentional actions do not

have the same positive or negative karmic effect, as interested and

intentional actions. In Buddhism, for example, actions that are

performed, or arise, or originate without any bad intent such as

covetousness, are considered non-existent in karmic impact or neutral in

influence to the individual.

Another causality characteristic, shared by Karmic theories, is

that like deeds lead to like effects. Thus good karma produces good

effect on the actor, while bad karma produces bad effect. This effect

may be material, moral or emotional — that is, one's karma affects one's

happiness and unhappiness.

The effect of karma need not be immediate; the effect of karma can be

later in one's current life, and in some schools it extends to future

lives.

The consequence or effects of one's karma can be described in two forms: phalas and samskaras. A phala

(literally, fruit or result) is the visible or invisible effect that is

typically immediate or within the current life. In contrast, samskaras

are invisible effects, produced inside the actor because of the karma,

transforming the agent and affecting his or her ability to be happy or

unhappy in this life and future ones. The theory of karma is often

presented in the context of samskaras.

Karmic principle can be understood, suggests Karl Potter, as a principle of psychology and habit. Karma seeds habits (vāsanā),

and habits create the nature of man. Karma also seeds self perception,

and perception influences how one experiences life events. Both habits

and self perception affect the course of one's life. Breaking bad habits

is not easy: it requires conscious karmic effort. Thus psyche and habit, according to Potter and others,

link karma to causality in ancient Indian literature. The idea of karma

may be compared to the notion of a person's "character", as both are an

assessment of the person and determined by that person's habitual

thinking and acting.

Karma and ethicization

The second theme common to karma theories is ethicization. This begins with the premise that every action has a consequence,

which will come to fruition in either this or a future life; thus,

morally good acts will have positive consequences, whereas bad acts will

produce negative results. An individual's present situation is thereby

explained by reference to actions in his present or in previous

lifetimes. Karma is not itself "reward and punishment", but the law that

produces consequence. Halbfass notes, good karma is considered as dharma and leads to punya (merit), while bad karma is considered adharma and leads to pāp (demerit, sin).

Reichenbach suggests that the theories of karma are an ethical theory.

This is so because the ancient scholars of India linked intent and

actual action to the merit, reward, demerit and punishment. A theory

without ethical premise would be a pure causal relation; the merit or

reward or demerit or punishment would be same regardless of the actor's

intent. In ethics, one's intentions, attitudes and desires matter in the

evaluation of one's action. Where the outcome is unintended, the moral

responsibility for it is less on the actor, even though causal

responsibility may be the same regardless.

A karma theory considers not only the action, but also actor's

intentions, attitude, and desires before and during the action. The

karma concept thus encourages each person to seek and live a moral life,

as well as avoid an immoral life. The meaning and significance of karma

is thus as a building block of an ethical theory.

Rebirth

The third common theme of karma theories is the concept of reincarnation or the cycle of rebirths (saṃsāra). Rebirth is a fundamental concept of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism.

The concept has been intensely debated in ancient literature of India;

with different schools of Indian religions considering the relevance of

rebirth as either essential, or secondary, or unnecessary fiction. Karma is a basic concept, rebirth is a derivative concept, so suggests Creel; Karma is a fact, asserts Yamunacharya, while reincarnation is a hypothesis; in contrast, Hiriyanna suggests rebirth is a necessary corollary of karma.

Rebirth, or saṃsāra, is the concept that all life forms go

through a cycle of reincarnation, that is a series of births and

rebirths. The rebirths and consequent life may be in different realm,

condition or form. The karma theories suggest that the realm, condition

and form depends on the quality and quantity of karma.

In schools that believe in rebirth, every living being's soul

transmigrates (recycles) after death, carrying the seeds of Karmic

impulses from life just completed, into another life and lifetime of

karmas. This cycle continues indefinitely, except for those who consciously break this cycle by reaching moksa. Those who break the cycle reach the realm of gods, those who don't continue in the cycle.

The theory of "karma and rebirth" raises numerous questions—such

as how, when, and why did the cycle start in the first place, what is

the relative Karmic merit of one karma versus another and why, and what

evidence is there that rebirth actually happens, among others. Various

schools of Hinduism realized these difficulties, debated their own

formulations, some reaching what they considered as internally

consistent theories, while other schools modified and de-emphasized it,

while a few schools in Hinduism such as Charvakas, Lokayatana abandoned "karma and rebirth" theory altogether. Schools of Buddhism consider karma-rebirth cycle as integral to their theories of soteriology.

Early development

The Vedic Sanskrit word kárman- (nominative kárma) means "work" or "deed", often used in the context of Srauta rituals.

In the Rigveda, the word occurs some 40 times. In Satapatha Brahmana 1.7.1.5, sacrifice is declared as the "greatest" of works; Satapatha Brahmana 10.1.4.1 associates the potential of becoming immortal (amara) with the karma of the agnicayana sacrifice.

The earliest clear discussion of the karma doctrine is in the Upanishads. For example, the causality and ethicization is stated in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 3.2.13 ("Truly, one becomes good through good deeds, and evil through evil deeds.")

Some authors state that the samsara (transmigration) and karma doctrine may be non-Vedic, and the ideas may have developed in the "shramana" traditions that preceded Buddhism and Jainism. Others

state that some of the complex ideas of the ancient emerging theory of

karma flowed from Vedic thinkers to Buddhist and Jain thinkers. The

mutual influences between the traditions is unclear, and likely

co-developed.

Many philosophical debates surrounding the concept are shared by

the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions, and the early developments in

each tradition incorporated different novel ideas.

For example, Buddhists allowed karma transfer from one person to

another and sraddha rites, but had difficulty defending the rationale. In contrast, Hindu schools and Jainism would not allow the possibility of karma transfer.

In Hinduism

The concept of karma in Hinduism developed and evolved over

centuries. The earliest Upanishads began with the questions about how

and why man is born, and what happens after death. As answers to the

latter, the early theories in these ancient Sanskrit documents include pancagni vidya (the five fire doctrine), pitryana (the cyclic path of fathers) and devayana (the cycle-transcending, path of the gods).

Those who do superficial rituals and seek material gain, claimed these

ancient scholars, travel the way of their fathers and recycle back into

another life; those who renounce these, go into the forest and pursue

spiritual knowledge, were claimed to climb into the higher path of the

gods. It is these who break the cycle and are not reborn. With the composition of the Epics – the common man's introduction to Dharma

in Hinduism – the ideas of causality and essential elements of the

theory of karma were being recited in folk stories. For example:

As a man himself sows, so he

himself reaps; no man inherits the good or evil act of another man. The

fruit is of the same quality as the action.

In the thirteenth book of the Mahabharata, also called the Teaching Book (Anushasana Parva),

sixth chapter opens with Yudhishthira asking Bhishma: "Is the course of

a person's life already destined, or can human effort shape one's

life?"

The future, replies Bhishma, is both a function of current human effort

derived from free will and past human actions that set the

circumstances.

Over and over again, the chapters of Mahabharata recite the key

postulates of karma theory. That is: intent and action (karma) has

consequences; karma lingers and doesn't disappear; and, all positive or

negative experiences in life require effort and intent. For example:

Happiness comes due to good actions, suffering results from evil actions,

by actions, all things are obtained, by inaction, nothing whatsoever is enjoyed.

If one's action bore no fruit, then everything would be of no avail,

if the world worked from fate alone, it would be neutralized.

Over time, various schools of Hinduism developed many different

definitions of karma, some making karma appear quite deterministic,

while others make room for free will and moral agency.[58]

Among the six most studied schools of Hinduism, the theory of karma

evolved in different ways, as their respective scholars reasoned and

attempted to address the internal inconsistencies, implications and

issues of the karma doctrine. According to Halbfass,

- The Nyaya school of Hinduism considers karma and rebirth as central, with some Nyaya scholars such as Udayana suggesting that the Karma doctrine implies that God exists.

- The Vaisesika school does not consider the karma from past lives doctrine very important.

- The Samkhya school considers karma to be of secondary importance (prakrti is primary).

- The Mimamsa school gives a negligible role to karma from past lives, disregards samsara and moksa.

- The Yoga school considers karma from past lives to be secondary,

one's behavior and psychology in the current life is what has

consequences and leads to entanglements.

- According to Professor Wilhelm Halbfass,

the Vedanta school acknowledges the karma-rebirth doctrine, but

concludes it is a theory that is not derived from reality and cannot be

proven, considers it invalid for its failure to explain evil /

inequality / other observable facts about society, treats it as a convenient fiction to solve practical problems in Upanishadic times, and declares it irrelevant.

In the Advaita Vedanta school, actions in current life have moral

consequences and liberation is possible within one's life as jivanmukti

(self-realized person).

The above six schools illustrate the diversity of views, but are not

exhaustive. Each school has sub-schools in Hinduism, such as Vedanta

school's nondualism and dualism sub-schools. Furthermore, there are

other schools of Hinduism such as Charvaka, Lokayata (the materialists)

who denied the theory of karma-rebirth as well as the existence of God;

to this school of Hindus, the properties of things come from the nature

of things. Causality emerges from the interaction, actions and nature of

things and people, determinative principles such as karma or God are

unnecessary.

In Buddhism

Karma and karmaphala are fundamental concepts in Buddhism. The concepts of karma and karmaphala explain how our intentional actions keep us tied to rebirth in samsara, whereas the Buddhist path, as exemplified in the Noble Eightfold Path, shows us the way out of samsara. Karmaphala is the "fruit", "effect" or "result" of karma. A similar term is karmavipaka, the "maturation" or "cooking" of karma.[note 1] The cycle of rebirth is determined by karma, literally "action". In the Buddhist tradition, karma refers to actions driven by intention (cetanā), a deed done deliberately through body, speech or mind, which leads to future consequences. The Nibbedhika Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya 6.63:

Intention (cetana) I tell you, is kamma. Intending, one does kamma by way of body, speech, & intellect.

How these intentional actions lead to rebirth, and how the idea of rebirth is to be reconciled with the doctrines of impermanence and no-self, is a matter of philosophical inquiry in the Buddhist traditions, for which several solutions have been proposed. In early Buddhism no explicit theory of rebirth and karma is worked out, and "the karma doctrine may have been incidental to early Buddhist soteriology." In early Buddhism, rebirth is ascribed to craving or ignorance.

The Buddha's teaching of karma is not strictly deterministic, but incorporated circumstantial factors, unlike that of the Jains. It is not a rigid and mechanical process, but a flexible, fluid and dynamic process. There is no set linear relationship between a particular action and its results.

The karmic effect of a deed is not determined solely by the deed

itself, but also by the nature of the person who commits the deed, and

by the circumstances in which it is committed. Karmaphala is not a "judgement" enforced by a God, Deity or other supernatural being that controls the affairs of the Cosmos. Rather, karmaphala is the outcome of a natural process of cause and effect.

Within Buddhism, the real importance of the doctrine of karma and its

fruits lies in the recognition of the urgency to put a stop to the whole

process. The Acintita Sutta warns that "the results of kamma" is one of the four incomprehensible subjects, subjects that are beyond all conceptualization and cannot be understood with logical thought or reason.

Nichiren Buddhism teaches that transformation and change through faith

and practice changes adverse karma—negative causes made in the past that

result in negative results in the present and future—to positive causes

for benefits in the future.

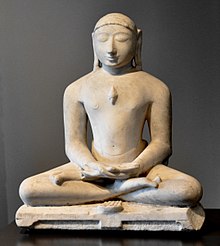

In Jainism

In Jainism, karma conveys a totally different meaning from that commonly understood in Hindu philosophy and western civilization. Jain philosophy is the oldest Indian philosophy that completely separates body (matter) from the soul (pure consciousness).

In Jainism, karma is referred to as karmic dirt, as it consists of very

subtle particles of matter that pervade the entire universe.

Karmas are attracted to the karmic field of a soul due to vibrations

created by activities of mind, speech, and body as well as various

mental dispositions. Hence the karmas are the subtle matter surrounding the consciousness of a soul. When these two components (consciousness and karma) interact, we experience the life we know at present.

Jain texts expound that seven tattvas (truths or fundamentals) constitute reality. These are:

- Jīva- the soul which is characterized by consciousness

- Ajīva- the non-soul

- Āsrava- inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul.

- Bandha (bondage)- mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas.

- Samvara (stoppage)- obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul.

- Nirjara (gradual dissociation)- separation or falling off of part of karmic matter from the soul.

- Mokṣha (liberation)- complete annihilation of all karmic matter (bound with any particular soul).

According to Padmanabh Jaini,

This

emphasis on reaping the fruits only of one's own karma was not

restricted to the Jainas; both Hindus and Buddhist writers have produced

doctrinal materials stressing the same point. Each of the latter

traditions, however, developed practices in basic contradiction to such

belief. In addition to shrardha (the ritual Hindu offerings by

the son of deceased), we find among Hindus widespread adherence to the

notion of divine intervention in ones fate, while Buddhists eventually

came to propound such theories like boon-granting bodhisattvas, transfer

of merit and like. Only Jainas have been absolutely unwilling to allow

such ideas to penetrate their community, despite the fact that there

must have been tremendous amount of social pressure on them to do so.

The relationship between the soul and karma, states Padmanabh Jaini,

can be explained with the analogy of gold. Like gold is always found

mixed with impurities in its original state, Jainism holds that the soul

is not pure at its origin but is always impure and defiled like natural

gold. One can exert effort and purify gold, similarly, Jainism states

that the defiled soul can be purified by proper refining methodology. Karma either defiles the soul further, or refines it to a cleaner state, and this affects future rebirths. Karma is thus an efficient cause (nimitta) in Jain philosophy, but not the material cause (upadana). The soul is believed to be the material cause.

The key points where the theory of karma in Jainism can be stated as follows:

- Karma operates as a self-sustaining mechanism as natural

universal law, without any need of an external entity to manage them.

(absence of the exogenous "Divine Entity" in Jainism)

- Jainism advocates that a soul attracts karmic matter even with the thoughts, and not just the actions. Thus, to even think evil of someone would endure a karma-bandha or an increment in bad karma. For this reason, Jainism emphasise on developing Ratnatraya (The Three Jewels): samyak darśana (Right Faith), samyak jnāna (Right Knowledge) and samyak charitra (Right Conduct).

- In Jain theology, a soul is released of worldly affairs as soon as it is able to emancipate from the "karma-bandha". In Jainism, nirvana and moksha are used interchangeably. Nirvana represents annihilation of all karmas by an individual soul and moksha represents the perfect blissful state (free from all bondage). In the presence of a Tirthankara, a soul can attain Kevala Jnana (omniscience) and subsequently nirvana, without any need of intervention by the Tirthankara.

- The karmic theory in Jainism operates endogenously. Even the Tirthankaras themselves have to go through the stages of emancipation, for attaining that state.

- Jainism treats all souls equally, inasmuch as it advocates that all

souls have the same potential of attaining nirvana. Only those who make

effort, really attain it, but nonetheless, each soul is capable on its

own to do so by gradually reducing its karma.

Reception in other traditions

Sikhism

In Sikhism, all living beings are described as being under the influence of maya's three qualities. Always present together in varying mix and degrees, these three qualities of maya

bind the soul to the body and to the earth plane. Above these three

qualities is the eternal time. Due to the influence of three modes of maya's nature, jivas

(individual beings) perform activities under the control and purview of

the eternal time. These activities are called "karma". The underlying

principle is that karma is the law that brings back the results of

actions to the person performing them.

This life is likened to a field in which our karma is the seed.

We harvest exactly what we sow; no less, no more. This infallible law of

karma holds everyone responsible for what the person is or is going to

be. Based on the total sum of past karma, some feel close to the Pure

Being in this life and others feel separated. This is the Gurbani's (Sri Guru Granth Sahib)

law of karma. Like other Indian and oriental schools of thought, the

Gurbani also accepts the doctrines of karma and reincarnation as the

facts of nature.

Shinto

Interpreted as musubi, a view of karma is recognized in Shinto as a means of enriching, empowering and life affirming.

Taoism

Karma is an important concept in Taoism.

Every deed is tracked by deities and spirits. Appropriate rewards or

retribution follow karma, just like a shadow follows a person.

The karma doctrine of Taoism developed in three stages.

In the first stage, causality between actions and consequences was

adopted, with supernatural beings keeping track of everyone's karma and

assigning fate (ming). In the second phase, transferability of

karma ideas from Chinese Buddhism were expanded, and a transfer or

inheritance of Karmic fate from ancestors to one's current life was

introduced. In the third stage of karma doctrine development, ideas of

rebirth based on karma were added. One could be reborn either as another

human being or another animal, according to this belief. In the third

stage, additional ideas were introduced; for example, rituals,

repentance and offerings at Taoist temples were encouraged as it could

alleviate Karmic burden.

Falun Gong

David Ownby, a scholar of Chinese history at the University of Montreal, asserts that Falun Gong

differs from Buddhism in its definition of the term "karma" in that it

is taken not as a process of award and punishment, but as an exclusively

negative term. The Chinese term "de" or "virtue" is reserved for

what might otherwise be termed "good karma" in Buddhism. Karma is

understood as the source of all suffering – what Buddhism might refer to

as "bad karma". Li says, "A person has done bad things over his many

lifetimes, and for people this results in misfortune, or for cultivators

it's karmic obstacles, so there's birth, aging, sickness, and death.

This is ordinary karma."

Falun Gong teaches that the spirit is locked in the cycle of rebirth, also known as samsara, due to the accumulation of karma.

This is a negative, black substance that accumulates in other

dimensions lifetime after lifetime, by doing bad deeds and thinking bad

thoughts. Falun Gong states that karma is the reason for suffering, and

what ultimately blocks people from the truth of the universe and

attaining enlightenment. At the same time, karma is also the cause of

one's continued rebirth and suffering.

Li says that due to accumulation of karma the human spirit upon death

will reincarnate over and over again, until the karma is paid off or

eliminated through cultivation, or the person is destroyed due to the

bad deeds he has done.

Ownby regards the concept of karma as a cornerstone to individual

moral behaviour in Falun Gong, and also readily traceable to the

Christian doctrine of "one reaps what one sows". Others say Matthew 5:44

means no unbeliever will not fully reap what they sow until they are

judged by God after death in Hell. Ownby says Falun Gong is

differentiated by a "system of transmigration", although, "in which each

organism is the reincarnation of a previous life form, its current form

having been determined by karmic calculation of the moral qualities of

the previous lives lived." Ownby says the seeming unfairness of manifest

inequities can then be explained, at the same time allowing a space for

moral behaviour in spite of them. In the same vein of Li's monism, matter and spirit are one, karma is identified as a black substance which must be purged in the process of cultivation.

Li says that "Human beings all fell here from the many dimensions

of the universe. They no longer met the requirements of the Fa at their

given levels in the universe, and thus had to drop down. Just as we

have said before, the heavier one's mortal attachments, the further down

one drops, with the descent continuing until one arrives at the state

of ordinary human beings." He says that in the eyes of higher beings,

the purpose of human life is not merely to be human, but to awaken

quickly on Earth, a "setting of delusion", and return. "That is what

they really have in mind; they are opening a door for you. Those who

fail to return will have no choice but to reincarnate, with this continuing until they amass a huge amount of karma and are destroyed."

Ownby regards this as the basis for Falun Gong's apparent "opposition to practitioners' taking medicine

when ill; they are missing an opportunity to work off karma by allowing

an illness to run its course (suffering depletes karma) or to fight the

illness through cultivation." Benjamin Penny

shares this interpretation. Since Li believes that "karma is the

primary factor that causes sickness in people", Penny asks: "if disease

comes from karma and karma can be eradicated through cultivation of xinxing, then what good will medicine do?"

Li himself states that he is not forbidding practitioners from taking

medicine, maintaining that "What I'm doing is telling people the

relationship between practicing cultivation and medicine-taking". Li

also states that "An everyday person needs to take medicine when he gets

sick." Schechter quotes a Falun Gong student who says "It is always an individual choice whether one should take medicine or not."

Discussion

Free will and destiny

One of the significant controversies with the karma doctrine is

whether it always implies destiny, and its implications on free will.

This controversy is also referred to as the moral agency problem; the controversy is not unique to karma doctrine, but also found in some form in monotheistic religions.

The free will controversy can be outlined in three parts:

(1) A person who kills, rapes or commits any other unjust act, can

claim all his bad actions were a product of his karma: he is devoid of

free will, he can not make a choice, he is an agent of karma, and he

merely delivers necessary punishments his "wicked" victims deserved for

their own karma in past lives. Are crimes and unjust actions due to free

will, or because of forces of karma? (2) Does a person who suffers from

the unnatural death of a loved one, or rape or any other unjust act,

assume a moral agent is responsible, that the harm is gratuitous, and

therefore seek justice? Or, should one blame oneself for bad karma over

past lives, and assume that the unjust suffering is fate? (3) Does the

karma doctrine undermine the incentive for moral education—because all

suffering is deserved and consequence of past lives, why learn anything

when the balance sheet of karma from past lives will determine one's

action and sufferings?

The explanations and replies to the above free will problem vary

by the specific school of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. The schools of

Hinduism, such as Yoga and Advaita Vedanta, that have emphasized

current life over the dynamics of karma residue moving across past

lives, allow free will.

Their argument, as well of other schools, are threefold: (1) The theory

of karma includes both the action and the intent behind that action.

Not only is one affected by past karma, one creates new karma whenever

one acts with intent – good or bad. If intent and act can be proven

beyond reasonable doubt, new karma can be proven, and the process of

justice can proceed against this new karma. The actor who kills, rapes

or commits any other unjust act, must be considered as the moral agent

for this new karma, and tried. (2) Life forms not only receive and reap

the consequence of their past karma, together they are the means to

initiate, evaluate, judge, give and deliver consequence of karma to

others. (3) Karma is a theory that explains some evils, not all (see moral evil versus natural evil).

Other schools of Hinduism, as well as Buddhism and Jainism that

do consider cycle of rebirths central to their beliefs and that karma

from past lives affects one's present, believe that both free will (Cetanā) and karma can co-exist; however, their answers have not persuaded all scholars.

Psychological indeterminacy

Another issue with the theory of karma is that it is psychologically indeterminate, suggests Obeyesekere.

That is, if no one can know what their karma was in previous lives, and

if the karma from past lives can determine one's future, then the

individual is psychologically unclear what if anything he or she can do

now to shape the future, be more happy, or reduce suffering. If

something goes wrong, such as sickness or failure at work, the

individual is unclear if karma from past lives was the cause, or the

sickness was caused by curable infection and the failure was caused by

something correctable.

This psychological indeterminacy problem is also not unique to

the theory of karma; it is found in every religion adopting the premise

that God has a plan, or in some way influences human events. As with the

karma-and-free-will problem above, schools that insist on primacy of

rebirths face the most controversy. Their answers to the psychological

indeterminacy issue are the same as those for addressing the free will

problem.

Transferability

Some schools of Asian religions, particularly Popular Theravada

Buddhism, allow transfer of karma merit and demerit from one person to

another. This transfer is an exchange of non-physical quality just like

an exchange of physical goods between two human beings. The practice of

karma transfer, or even its possibility, is controversial. Karma transfer raises questions similar to those with substitutionary atonement

and vicarious punishment. It defeats the ethical foundations, and

dissociates the causality and ethicization in the theory of karma from

the moral agent. Proponents of some Buddhist schools suggest that the

concept of karma merit transfer encourages religious giving, and such

transfers are not a mechanism to transfer bad karma (i.e., demerit) from

one person to another.

In Hinduism, Sraddha rites during funerals have been labelled as

karma merit transfer ceremonies by a few scholars, a claim disputed by

others.

Other schools in Hinduism, such as the Yoga and Advaita Vedantic

philosophies, and Jainism hold that karma can not be transferred.

The problem of evil

There has been an ongoing debate about karma theory and how it answers the problem of evil and related problem of theodicy. The problem of evil is a significant question debated in monotheistic religions with two beliefs: (1) There is one God who is absolutely good and compassionate (omnibenevolent),

and (2) That one God knows absolutely everything (omniscient) and is

all powerful (omnipotent). The problem of evil is then stated in

formulations such as, "why does the omnibenevolent, omniscient and

omnipotent God allow any evil and suffering to exist in the world?" Max

Weber extended the problem of evil to Eastern traditions.

The problem of evil, in the context of karma, has been long

discussed in Eastern traditions, both in theistic and non-theistic

schools; for example, in Uttara Mīmāṃsā Sutras Book 2 Chapter 1; the 8th century arguments by Adi Sankara in Brahmasutrabhasya

where he posits that God cannot reasonably be the cause of the world

because there exists moral evil, inequality, cruelty and suffering in

the world; and the 11th century theodicy discussion by Ramanuja in Sribhasya.

Epics such as the Mahabharata, for example, suggests three prevailing

theories in ancient India as to why good and evil exists – one being

that everything is ordained by God, another being karma, and a third

citing chance events (yadrccha, यदृच्छा).

The Mahabharata, which includes Hindu deity Vishnu in the form of

Krishna as one of the central characters in the Epic, debates the nature

and existence of suffering from these three perspectives, and includes a

theory of suffering as arising from an interplay of chance events (such

as floods and other events of nature), circumstances created by past

human actions, and the current desires, volitions, dharma, adharma and

current actions (purusakara) of people.

However, while karma theory in the Mahabharata presents alternative

perspectives on the problem of evil and suffering, it offers no

conclusive answer.

Other scholars suggest that nontheistic Indian religious traditions do not assume an omnibenevolent creator, and some

theistic schools do not define or characterize their God(s) as

monotheistic Western religions do and the deities have colorful, complex

personalities; the Indian deities are personal and cosmic facilitators,

and in some schools conceptualized like Plato's Demiurge.

Therefore, the problem of theodicy in many schools of major Indian

religions is not significant, or at least is of a different nature than

in Western religions.

Many Indian religions place greater emphasis on developing the karma

principle for first cause and innate justice with Man as focus, rather

than developing religious principles with the nature and powers of God

and divine judgment as focus. Some scholars, particularly of the Nyaya school of Hinduism and Sankara in Brahmasutra bhasya,

have posited that karma doctrine implies existence of god, who

administers and affects the person's environment given that person's

karma, but then acknowledge that it makes karma as violable, contingent

and unable to address the problem of evil.

Arthur Herman states that karma-transmigration theory solves all three

historical formulations to the problem of evil while acknowledging the

theodicy insights of Sankara and Ramanuja.

Some theistic Indian religions, such as Sikhism, suggest evil and

suffering are a human phenomenon and arises from the karma of

individuals. In other theistic schools such as those in Hinduism, particularly its Nyaya school, karma is combined with dharma and evil is explained as arising from human actions and intent that is in conflict with dharma.

In nontheistic religions such as Buddhism, Jainism and the Mimamsa

school of Hinduism, karma theory is used to explain the cause of evil as

well as to offer distinct ways to avoid or be unaffected by evil in the

world.

Those schools of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism that rely on

karma-rebirth theory have been critiqued for their theological

explanation of suffering in children by birth, as the result of his or

her sins in a past life. Others disagree, and consider the critique as flawed and a misunderstanding of the karma theory.

Comparable concepts

It Shoots Further Than He Dreams by John F. Knott, March 1918.

Western culture, influenced by Christianity, holds a notion similar to karma, as demonstrated in the phrase "what goes around comes around".

Christianity

Mary Jo Meadow suggests karma is akin to "Christian notions of sin and its effects." She states that the Christian teaching on a Last Judgment according to one's charity is a teaching on karma. Christianity also teaches morals such as one reaps what one sows (Galatians 6:7) and live by the sword, die by the sword (Matthew 26:52).

Most scholars, however, consider the concept of Last Judgment as

different from karma, with karma as an ongoing process that occurs every

day in one's life, while Last Judgment, by contrast, is a one-time

review at the end of life.

Judaism

There is a concept in Judaism called in Hebrew midah k'neged midah,

which literally translates to "value against value," but carries the

same connotation as the English phrase "measure for measure." The

concept is used not so much in matters of law, but rather, in matters of

ethics, i.e. how one's actions affects the world will eventually come

back to that person in ways one might not necessarily expect. David Wolpe compared midah k'neged midah to karma.

Psychoanalysis

Jung once opined on unresolved emotions and the synchronicity of karma;

When an inner situation is not made conscious, it appears outside as fate.

Popular methods for negating cognitive dissonance include meditation, metacognition, counselling, psychoanalysis,

etc., whose aim is to enhance emotional self-awareness and thus avoid

negative karma. This results in better emotional hygiene and reduced

karmic impacts. Permanent neuronal changes within the amygdala and left prefrontal cortex of the human brain attributed to long-term meditation and metacognition techniques have been proven scientifically. This process of emotional maturation aspires to a goal of Individuation or self-actualisation. Such peak experiences are hypothetically devoid of any karma (nirvana or moksha).

Theosophy, Spiritism, New Age

The idea of karma was popularized in the Western world through the work of the Theosophical Society. In this conception, karma was a precursor to the Neopagan law of return or Threefold Law,

the idea that the beneficial or harmful effects one has on the world

will return to oneself. Colloquially this may be summed up as 'what goes

around comes around.'

The Theosophist I. K. Taimni

wrote, "Karma is nothing but the Law of Cause and Effect operating in

the realm of human life and bringing about adjustments between an

individual and other individuals whom he has affected by his thoughts,

emotions and actions." Theosophy also teaches that when humans reincarnate they come back as humans only, not as animals or other organisms.