Racial or ethnic profiling is the act of suspecting or targeting a person on the basis of assumed characteristics or behavior of a racial or ethnic group, rather than on individual suspicion. Racial profiling, however, is not limited only to an individual's ethnicity or race, but can also be based on the individual's religion, or national origin. In European countries, the term "ethnic profiling" is also used instead of racial profiling.

Canada

Accusations of racial profiling of visible minorities who accuse police of targeting them due to their ethnic background is a growing concern in Canada. In 2005, the Kingston Police released the first study ever in Canada which pertains to racial profiling. The study focused on the city of Kingston, Ontario, a small city where most of the inhabitants are white. The study showed that black-skinned people were 3.7 times more likely to be pulled over by police than white-skinned people, while Asian and White people are less likely to be pulled over than more than Black people. Several police organizations condemned this study and suggested more studies like this would make them hesitant to pull over visible minorities.

Canadian Aboriginals are more likely to be charged with crimes, particularly on reserves. The Canadian crime victimization survey does not collect data on the ethnic origin of perpetrators, so comparisons between incidence of victimizations and incidence of charging are impossible. Although aboriginal persons make up 3.6% of Canada's population, they account for 20% of Canada's prison population. This may show how racial profiling increases effectiveness of police, or be a result of racial profiling, as they are watched more intensely than others.

In February 2010, an investigation of the Toronto Star daily newspaper found that black people across Toronto were three times more likely to be stopped and documented by police than white people. To a lesser extent, the same seemed true for people described by police as having "brown" skin (South Asians, Arabs and Latinos). This was the result of an analysis of 1.7 million contact cards filled out by Toronto Police officers in the period 2003–2008.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission states that "police services have acknowledged that racial profiling does occur and have taken [and are taking] measures to address [the issue], including upgrading training for officers, identifying officers at risk of engaging in racial profiling, and improving community relations". Ottawa Police addressed this issue and planned on implementing a new policy regarding officer racially profiling persons, "the policy explicitly forbids officers from investigating or detaining anyone based on their race and will force officers to go through training on racial profiling".

This policy was implemented after the 2008 incident where an African-Canadian woman was strip searched by members of the Ottawa police. There is a video showing the strip search where one witnesses the black woman being held to the ground and then having her bra and shirt cut ripped/cut off by a member of the Ottawa Police Force which was released to the viewing of the public in 2010.

China

The Chinese government has been using a facial recognition technology, analysing output of surveillance cameras to track and control Uyghurs, a Muslim minority in China's Western province of Xinjiang. The extent of the vast system was published in the spring of 2019 by the NYT who called it "automated racism". In research projects aided by European institutions it has combined the facial output with people's DNA, to create an ethnic profile. The DNA was collected at the prison camps, which are interning more than one million Uyghurs, as had been corroborated in November 2019 by data leaks, such as the China Cables.

Germany

In February 2012, the first court ruling concerning racial profiling in German police policy, allowing police to use skin color and "non-German ethnic origin" to select persons who will be asked for identification in spot-checks for illegal immigrants. Subsequently, it was decided legal for a person submitted to a spot-check to compare the policy to that of the SS in public. A higher court later overruled the earlier decision declaring the racial profiling unlawful and in violation of anti-discrimination provisions in Art. 3 Basic Law and the General Equal Treatment Act of 2006.

The civil rights organisation Büro zur Umsetzung von Gleichbehandlung (Office for the Implementation of Equal Treatment) makes a distinction between criminal profiling, which is legitimate in Germany, and ethnic profiling, which is not.

According to a 2016 report by the Interior ministry in Germany, there had been an increase in hate crimes and violence against migrant groups in Germany. The reports concluded that there were more than 10 attacks per day against migrants in Germany in 2016. This report from Germany garnered the attention of the United Nations, which alleged that people of African descent face widespread discrimination in Germany.

A 2016 statement by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights after a visit to Germany said that "although the [German] constitution guarantees equality, bans racial discrimination and enshrines the inviolability of human dignity, these principles are not put into practice." and called racial profiling against Africans endemic.

Israel

In 1972, terrorists from the Japanese Red Army launched an attack that led to the deaths of at least 24 people at Ben Gurion Airport. Since then, security at the airport has relied on a number of fundamentals, including a heavy focus on what Raphael Ron, former director of security at Ben Gurion, terms the "human factor", which he generalized as "the inescapable fact that terrorist attacks are carried out by people who can be found and stopped by an effective security methodology." As part of its focus on this so-called "human factor," Israeli security officers interrogate travelers using racial profiling, singling out those who appear to be Arab based on name or physical appearance. Additionally, all passengers, including those who do not appear to be of Arab descent, are questioned as to why they are traveling to Israel, followed by several general questions about the trip in order to search for inconsistencies.

Although numerous civil rights groups have demanded an end to the profiling, the Israeli government maintains that it is both effective and unavoidable. According to Ariel Merari, an Israeli terrorism expert, "it would be foolish not to use profiling when everyone knows that most terrorists come from certain ethnic groups. They are likely to be Muslim and young, and the potential threat justifies inconveniencing a certain ethnic group."

Mexico

The General Law on Population (Reglamento de la Ley General de Poblacion) of 2000 in Mexico has been cited as being used to racially profile and abuse immigrants to Mexico. Mexican law makes illegal immigration punishable by law and allows law officials great discretion in identifying and questioning illegal immigrants. Mexico has been criticized for its immigration policy. Chris Hawley of USA Today stated that "Mexico has a law that is no different from Arizona's", referring to legislation which gives local police forces the power to check documents of people suspected of being in the country illegally. Immigration and human rights activists have also noted that Mexican authorities frequently engage in racial profiling, harassment, and shakedowns against migrants from Central America.

Spain

Racial profiling by police forces in Spain is a common practice. A study by the University of Valencia, found that people of non-white aspect are up to ten times more likely to be stopped by the police on the street. Amnesty International accused Spanish authorities of using racial and ethnic profiling, with police singling out people who do not look Caucasian in the street and public places.

In 2011, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) urged the Spanish government to take "effective measures" to ethnic profiling, including the modification of existing laws and regulations which permit its practice. In 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur, Mutuma Ruteere, described the practice of ethnic profiling by Spanish law enforcement officers "a persisting and pervasive problem". In 2014, the Spanish government approved a law which prohibited racial profiling by police forces.

United States

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU):

'Racial profiling' refers to the practice by law enforcement officials of targeting individuals for suspicion of crime based on the individual's race, ethnicity, religion or national origin. Criminal profiling, generally, as practiced by police, is the reliance on a group of characteristics they believe to be associated with crime which unfortunately leads to innocent people dying. Examples of racial profiling are the use of race to determine which drivers to stop for minor traffic violations (commonly referred to as 'driving while black, Asian, Native American, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, or brown'), or the use of race to determine which pedestrians to search for illegal contraband.

Besides such disproportionate searching of African Americans, and members of other minority groups, other examples of racial profiling by law enforcement in the U.S. include the targeting of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the investigation of illegal immigration; and the focus on Middle Eastern and South Asians present in the country in screenings for ties to Islamic terrorism. These suspicions may be held on the basis of belief that members of a target racial group commit crimes at a higher rate than that of other racial groups.

According to Minnesota House of Representatives analyst Jim Cleary, "there appears to be at least two clearly distinguishable definitions of the term 'racial profiling': a narrow definition and a broad definition... Under the narrow definition, racial profiling occurs when a police officer stops and/or searches someone solely on the basis of the person's race or ethnicity... Under the broader definition, racial profiling occurs whenever police routinely use race as a factor that, along with an accumulation of other factors, causes an officer to react with suspicion and take action."

A study conducted by Domestic Human Rights Program of Amnesty International USA, found that racial profiling had increased from the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks to 2004, and that state laws had provided inconsistent and insufficient protections against racial profiling.

More commonly in the United States, racial profiling is referred to regarding its use by law enforcement at the local, state, and federal levels, and its use leading to discrimination against people in the African American, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, Latino, Arab, and Muslim communities of the U.S.

History

Sociologist Robert Staples emphasizes that racial profiling in the U.S. is "not merely a collection of individual offenses" but, rather, a systemic phenomenon across American society, dating back to the era of slavery, and, until the 1950s, was, in some instances, "codified into law". Enshrinement of racial profiling ideals in United States law can be exemplified by several major periods in U.S. history.

In 1693, Philadelphia's court officials gave police legal authority to stop and detain any Negro (freed or enslaved) seen wandering about. Starting around the mid 18th century, slave patrols were used to stop slaves at any location in order to ensure they were being lawful. In the mid 19th century, the Black Codes, a set of statutes, laws and rules, were enacted in the South in order to regain control over freed and former slaves and relegate African Americans to a lower social status. Similar discriminatory practices continued through the Jim Crow era.

Prior to U.S. immigration restrictions following the September 11 attacks, Japanese immigrants were rejected U.S. citizenship during World War II, for fear of disloyalty following the attacks on Pearl Harbor. What resulted was the government's preemptive internment of more than 100,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese American citizens during World War II, as a measure against potential Japanese espionage, constituting a form of racial profiling.

In the late 1990s racial profiling became politicized when police and other law enforcement fell under scrutiny for the disproportionate traffic stops of minority motorists. Researchers from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) provided evidence of widespread racial profiling, one study showed that while blacks only made up 42 percent of New Jersey's driving population, they accounted for 79 percent of motorists stopped in the state.

Supreme Court cases

Terry v. Ohio was the first challenge to racial profiling in the United States in 1968. This case was about African American people who were thought to be stealing. The police officer arrested the three men and searched them and found a gun on two of the three men, and John W. Terry (one of the three men searched) was convicted and sentenced to jail. Terry challenged the arrest on the grounds that it violated the search and seizure clause of the Fourth Amendment; however, in an 8-1 ruling, the Supreme Court decided that the police officer acted in a reasonable manner, and with reasonable suspicion, under the Fourth Amendment. The decision in this case allowed for greater police discretion in identifying suspicious or illegal activities.

In 1975, United States v. Brignoni-Ponce was decided. Felix Humberto Brignoni-Ponce was traveling in his vehicle and was stopped by border patrol agents because he appeared to be Mexican. The agents questioned Brignoni-Ponce and the other passengers in the car and discovered that the passengers were illegal immigrants, and the border agents subsequently arrested all occupants of the vehicle. The Supreme Court determined that the testimonies that led to the arrests, in this case, were not valid, as they were obtained in the absence of reasonable suspicion and the vehicle was stopped without probable cause, as required under the Fourth Amendment.

In 1996, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Armstrong that disparity in conviction rates is not unconstitutional in the absence of data that "similarly situated" defendants of another race were disparately prosecuted, overturning a 9th Circuit Court ruling that was based on "the presumption that people of all races commit all types of crimes – not with the premise that any type of crime is the exclusive province of any particular racial or ethnic group", waving away challenges based on the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution which guarantees the right to be safe from search and seizure without a warrant (which is to be issued "upon probable cause"), and the Fourteenth Amendment which requires that all citizens be treated equally under the law. To date, there have been no known cases in which any U.S. court dismissed a criminal prosecution because the defendant was targeted based on race. This Supreme Court decision doesn't prohibit government agencies from enacting policies prohibiting it in the field by agents and employees.

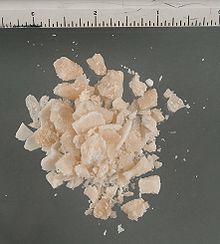

The Supreme Court also decided the case of Whren v. United States in 1996. Michael Whren was arrested on felony drug charges after police officers observed his truck sitting at an intersection for a long period of time before he failed to use his turn signal to drive away, and the officers stopped his vehicle for the traffic violation. Upon approaching the vehicle the officers observed that Whren was in possession of crack cocaine. The Court determined the officers did not violate the Fourth Amendment through an unreasonable search and seizure and that the officers were permitted to stop the vehicle after it committed a traffic violation and the subsequent search of the vehicle was permitted regardless of the pretext of the officers.

In June 2001 the Bureau of Justice Assistance, a component of the Office of Justice Programs of the United States Department of Justice, awarded a Northeastern research team a grant to create the web-based Racial Profiling Data Collection Resource Center. It now maintains a website designed to be a central clearinghouse for police agencies, legislators, community leaders, social scientists, legal researchers, and journalists to access information about current data collection efforts, legislation and model policies, police-community initiatives, and methodological tools that can be used to collect and analyze racial profiling data. The website contains information on the background of data collection, jurisdictions currently collecting data, community groups, legislation that is pending and enacted in states across the country, and has information on planning and implementing data collection procedures, training officers in to implement these systems, and analyzing and reporting the data and results.

Statutory law

In April 2010, Arizona enacted SB 1070, a law that would require law-enforcement officers to verify the citizenship of individuals they stop if they have reasonable suspicion that they may be in the United States illegally. The law states that "Any person who is arrested shall have the person's immigration status determined before the person is released". United States federal law requires that all immigrants who remain in the United States for more than 30 days register with the U.S. government. In addition, all immigrants age 18 and over are required to have their registration documents with them at all times. Arizona made it a misdemeanor crime for an illegal immigrant 14 years of age and older to be found without carrying these documents at all times.

According to SB 1070, law-enforcement officials may not consider "race, color, or national origin" in the enforcement of the law, except under the circumstances allowed under the United States and Arizona constitutions. In June 2012, the majority of SB 1070 was struck down by the United States Supreme Court, while the provision allowing for an immigration check on detained persons was upheld.

Some states contain "stop and identify" laws that allow officers to detain suspected persons and ask for identification, and if there is a failure to provide identification punitive measures can be taken by the officer. As of 2017, there are 24 states that have "stop and identify" statues; however, the criminal punishments and requirements to produce identification vary from state to state. Utah HB 497 requires residents to carry relevant identification at all times in order to prove resident status or immigration status; even so, police may still dismiss provided documents under suspicion of falsification and arrest or detain suspects.

In early 2001, a bill was introduced to Congress named "End Racial Profiling Act of 2001" but lost support in the wake of the September 11 attacks. The bill was re-introduced to Congress in 2010 but also failed to gain the support it needed. Several U.S. states now have reporting requirements for incidents of racial profiling. Texas, for example, requires all agencies to provide annual reports to its Law Enforcement Commission. The requirement began on September 1, 2001, when the State of Texas passed a law to require all law enforcement agencies in the state to begin collecting certain data in connection to traffic or pedestrian stops beginning on January 1, 2002. Based on that data, the law mandated law enforcement agencies to submit a report to the law enforcement agencies' governing body beginning March 1, 2003 and each year thereafter no later than March 1. The law is found in the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure beginning with Article 2.131.

Additionally, on January 1, 2011, all Texas law enforcement agencies began submitting annual reports to the Texas State Law Enforcement Officers Standards and Education Commission. The submitted reports can be accessed on the Commission's website for public review.

In June 2003, the Department of Justice issued its Guidance Regarding the Use of Race by Federal Law Enforcement Agencies forbidding racial profiling by federal law enforcement officials.

Support

Supporters defend the practice of racial profiling by emphasizing the crime control model. They claim that the practice is both efficient and ideal due to utilizing the laws of probability in order to determine one's criminality. This system focuses on controlling crime with swift judgment, bestowing full discretion on police to handle what they perceive as a threat to society.

The use and support of racial profiling has surged in recent years, namely in North America due to heightened tension and awareness following the events of 9/11. As a result, the issue of profiling has created a debate that centers on the values of equality and self-defense. Supporters uphold the stance that sacrifices must be made in order to maintain national safety, even if it warrants differential treatment. According to a 2011 survey by Rasmussen Reports, a majority of Americans support profiling as necessary "in today's society".

In December 2010, Fernando Mateo, then president of the New York State Federation of Taxi Drivers, made pro-racial profiling remarks in the case of gun-shot taxi-cab driver: "You know sometimes it's good that we are racially profiled because the God's-honest truth is that 99 percent of the people that are robbing, stealing, killing these drivers are blacks and Hispanics." "Clearly everyone knows I'm not racist. I'm Hispanic and my father is black. ... My father is blacker than Al Sharpton." When confronted with accusations of racial profiling the police claim that they do not participate in it. They emphasize that numerous factors (such as race, interactions, and dress) are used to determine if a person is involved in criminal activity and that race is not a sole factor in the decision to detain or question an individual. They further claim that the job of policing is far more imperative than to concerns of minorities or interest groups claiming unfair targeting.

Proponents of racial profiling believe that inner city residents of Hispanic communities are subjected to racial profiling because of theories such as the "gang suppression model". The "gang suppression model" is believed by some to be the basis for increased policing, the theory being based on the idea that Latinos are violent and out of control and are therefore "in need of suppression". Based on research, the criminalization of a people can lead to abuses of power on behalf of law enforcement.

Criticism

Critics of racial profiling argue that the individual rights of a suspect are violated if race is used as a factor in that suspicion. Notably, civil liberties organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have labeled racial profiling as a form of discrimination, stating, "Discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, nationality or on any other particular identity undermines the basic human rights and freedoms to which every person is entitled."

Conversely, those in opposition of the police tactic employ the teachings of the due process model, arguing that minorities are not granted equal rights and are thus subject to unjust treatment. In addition, some argue that the singling out of individuals based on their ethnicity comes in violation of the Rule of Law, having voided all instance of neutrality. Those in opposition also make note of the role that the news media plays within the conflict. The general public internalizes much of its knowledge from the media, relying on sources to convey information of events that transpire outside of their immediate domain. In conjunction with this power, media outlets are aware of the public's intrigue with controversy and have been known to construct headlines that entail moral panic and negativity.

In the case of racial profiling drivers, the ethnic backgrounds of drivers stopped by traffic police in the U.S. suggests the possibility of biased policing against non-white drivers. Black drivers felt that they were being pulled over by law enforcement officers simply because of their skin color. However, some argue in favor of the "veil of darkness" hypothesis, which states that police are less likely to know the race of a driver before they make a stop at nighttime as opposed to in the daytime. Referring to the veil of darkness hypothesis, it is suggested that if the race distribution of drivers stopped during the day differs from that of drivers stopped at night, officers are engaging in racial profiling. For example, in one study done by Jeffrey Grogger and Greg Ridgeway, the veil of darkness hypothesis was used to determine whether or not racial profiling in traffic stops occurs in Oakland, California. The conductors found that there was little evidence of racial profiling in traffic stops made in Oakland.

Research through random sampling in the South Tucson, Arizona area has established that immigration authorities sometimes target the residents of barrios with the use of possibly discriminatory policing based on racial profiling. Author Mary Romero writes that immigration raids are often carried out at places of gathering and cultural expression such as grocery stores based on the fluency of language of a person (e.g. being bilingual especially in Spanish) and skin color of a person. She goes on to state that immigration raids are often conducted with a disregard for due process, and that these raids lead people from these communities to distrust law enforcement.

In a recent journal comparing the 1990s to the present, studies have established that when the community criticized police for targeting the black community during traffic stops it received more media coverage and toned down racial profiling. However, whenever there was a significant lack of media coverage or concern with racial profiling, the amount of arrests and traffic stops for the African-American community would significantly rise again.

New York Police Department

Suspicionless surveillance of Muslims

Between 2003 and 2014, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) operated the "Demographics Unit" (later renamed "Zone Assessment Unit") which mapped communities of 28 "ancestries of interest", including those of Muslims, Arabs, and Albanians. Plain-clothed detectives were sent to public places such as coffee shops, mosques and parks to observe and record the public sentiment, as well as map locations where potential terrorists could "blend in". In its 11 years of operation, however, the unit did not generate any information leading to a criminal charge. A series of publications by the Associated Press during 2011–12 gave rise to public pressure to close the unit, and it was finally disbanded in 2014.

Racial profiling not only occurs on the streets but also in many institutions. Much like the book Famous all over Town where the author Danny Santiago mentions this type of racism throughout the novel. According to Jesper Ryberg's 2011 article "Racial Profiling And Criminal Justice" in the Journal of Ethics, "It is argued that, given the assumption that criminals are currently being punished too severely in Western countries, the apprehension of more criminals may not constitute a reason in favor of racial profiling at all." It has been stated in a scholarly journal that for over 30 years the use of racial and/or demographic profiling by local authorities and higher level law enforcement's continue to proceed. NYPD Street cops use racial profiling more often, due to the widespread patterns. They first frisk them to check whether they have enough evidence to be even arrested for the relevant crime. "As a practical matter, the stops display a measurable racial disparity: black and Hispanic people generally represent more than 85 percent of those stopped by the police, though their combined populations make up a small share of the city's racial composition." (Baker)

Stop-and-frisk

The NYPD has been subject to much criticism for its "stop-and-frisk" tactics. According to statistics on the NYPD's stop and frisk policies, collected by the Center for Constitutional Rights, 51% of the people stopped by the police were Black, 33% were Latino, and 9% were White, and only 2% of all stops resulted in contraband findings. Starting in 2013, use of racial profiling by the NYPD was drastically curtailed, as New York Mayor Bill de Blasio was campaigning for the office, and this policy has continued into his term.

In June 2019, the independent Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD (OIG-NYPD), under New York City's Department of Investigation (DOI), released a report which found deficiencies in how NYPD tracked and investigated allegations of racial profiling and other types of biased policing against NYPD officers. The report concluded that NYPD had never substantiated any complaints of biased policing since it began tracking them in 2014.

Dealing with terrorism

The September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon have led to targeting of some Muslims and Middle Easterners as potential terrorists and, according to some, are targeted by the national government through preventive measures similar to those practiced by local law enforcement. The national government has passed laws, such as the Patriot Act of 2001, to increase surveillance of potential threats to national security as a result of the events that occurred during 9/11. It is argued that the passage of these laws and provisions by the national government leads to justification of preventative methods, such as racial profiling, that has been controversial for racial profiling and leads to further minority distrust in the national government. One of the techniques used by the FBI to target Muslims was monitoring 100 mosques and business in Washington DC and threatened to deport Muslims who did not agree to serve as informers. The FBI denied to be taking part in blanket profiling and argued that they were trying to build trust within the Muslim community.

On September 14, 2001, three days after the September 11th attacks, an Indian American motorist and three family members were pulled over and ticketed by a Maryland state trooper because their car had broken taillights. The trooper interrogated the family, questioned them about their nationality, and asked for proof of citizenship. When the motorist said that their passports were at home, the officer allegedly stated, "You are lying. You are Arabs involved in terrorism." He ordered them out of the car, had them put their hands on the hood, and searched the car. When he discovered a knife in a toolbox, the officer handcuffed the driver and later reported that the driver "wore and carried a butcher knife, a dangerous, deadly weapon, concealed upon and about his person." The driver was detained for several hours but eventually released.

In December 2001, an American citizen of Middle Eastern descent named Assem Bayaa cleared all the security checks at Los Angeles airport and attempted to board a flight to New York City. Upon boarding, he was told that he made the passengers uncomfortable by being on board the plane and was asked to leave. Once off the plane, he wasn't searched or questioned any further and the only consolation he was given was a boarding pass for the next flight. He filed a lawsuit on the basis of discrimination against United Airlines. United Airlines filed a counter motion which was dismissed by a district judge on October 11, 2002. In June 2005, the ACLU announced a settlement between Bayaa and United Airlines who still disputed Bayaa's allegations, but noted that the settlement "was in the best interest of all".

The events of 9/11 also led to restrictions in immigration laws. The U.S. government imposed stricter immigration quotas to maintain national security at their national borders. In 2002, men over sixteen years old who entered the country from twenty-five Middle Eastern countries and North Korea were required to be photographed, fingerprinted, interviewed and have their financial information copied, and had to register again before leaving the country under the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System. No charges of terrorism resulted from the program, and it was deactivated in April 2011.

In 2006, 18 young men from the Greater Toronto Area were charged with conspiring to carry out a series of bombings and beheadings, resulting in a swell of media coverage. Two media narratives stood out with the former claiming that a militant subculture was forming within the Islamic community while the latter attributed the case to a bunch of deviant youth who had too much testosterone brewing.

Eventually, it was shown that government officials had been tracking the group for some time, having supplied the youth with the necessary compounds to create explosives, prompting critics to discern whether the whole situation was a set-up. Throughout the case, many factors were put into question but none more than the Muslim community who faced much scrutiny and vitriol due to the build-up of negative headlines stemming from the media.

Studies

Statistical data demonstrates that although policing practices and policies vary widely across the United States, a large disparity between racial groups in regards to traffic stops and searches exists. However, whether this is due to racial profiling or the fact that different races are involved in crime in different rates, is still highly debated. Based on academic search, various studies have been conducted regarding the existence of racial profiling in traffic and pedestrian stops. For motor vehicle searches, academic research showed that the probability of a successful search is very similar across races. This suggests that police officers are not motivated by racial preferences but by the desire to maximize the probability of a successful search. Similar evidence has been found for pedestrian stops, with identical ratios of stops to arrests for different races.

The studies have been published in various Academic Journals aimed towards Academic professionals as well practitioners such as law enforcers. Some of these journals include, Police Quarterly and the Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, so that both sides of the argument are present and evaluated. Of those gathered the most noted study refuting racial profiling was the conducted using the veil of darkness hypothesis stating that it will be difficult, if not impossible, for officers to discern race in the twilight hours. The results of this study concluded that the ratio of different races stopped by New York cops is about the same for all races tested.

Some of the most referenced organizations, who offer evidence on the existence of racial profiling, are The American Civil Liberties Union, which conducted studies in various major U.S. cities, and RAND. In a study conducted in Cincinnati, Ohio, it was concluded that "Blacks were between three and five times more likely to (a) be asked if they were carrying drugs or weapons, (b) be asked to leave the vehicle, (c) be searched, (d) have a passenger searched, and (e) have the vehicle physically searched in a study conducted. This conclusion was based on the analysis of 313 randomly selected, traffic stop police tapes gathered from 2003 to 2004."

A 2001 study analyzing data from the Richmond, Virginia Police Department found that African Americans were disproportionately stopped compared to their proportion in the general population, but that they were not searched more often than Whites. The same study found that Whites were more likely than African Americans to be "the subjects of consent searches," and that Whites were more likely to be ticked or arrested than minorities, while minorities were more likely to be warned. A 2002 study found that African Americans were more likely to be watched and stopped by police when driving through white areas, despite the fact that African Americans' "hit rates" were lower in such areas. A 2004 study analyzing traffic stop data from suburban police department found that although minorities were disproportionately stopped, there is only a "very weak" relationship between race and police decisions to stop. Another 2004 study found that young black and Hispanic men were more likely to be issued citations, arrested, and to have force used against them by police, even after controlling for numerous other factors.

A 2005 study found that the percent of speeding drivers who were black (as identified by other drivers) on the New Jersey Turnpike was very similar to the percent of people pulled over for speeding who were black. A 2004 study looking at motor vehicle searches in Missouri found that unbiased policing did not explain the racial disparity in such searches. In contrast, a 2006 study examining data from Kansas concluded that its results were "consistent with the notion that police in Wichita choose their search strategies to maximize successful searches," and a 2009 study found that racial disparities in people being searched by the Washington state patrol was "likely not the result of intentional or purposeful discrimination." Another 2009 study found that police in Boston were more likely to search if their race was different from that of the suspect, in contrast to what would be expected if preference based discrimination was not occurring (which would be that police search decisions are independent of officer race).

A 2010 study found that black drivers were more likely to be searched at traffic stops in white neighborhoods, whereas white drivers were more likely to be searched by white officers at stops in black neighborhoods. A 2013 study found that police were more likely to issue warnings and citations, but not arrests, to young black men. A 2014 study analyzing data from Rhode Island found that blacks were more likely than whites to be frisked and, to a lesser extent, searched while driving; the study concluded that "Biased policing is largely the product of implicit stereotypes that are activated in contexts in which Black drivers appear out of place and in police actions that require quick decisions providing little time to monitor cognitions."

As a response to the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson on August 9, 2014, the Department of Justice recruited in September a team of criminal justice researchers to study racial bias in law enforcement in five cities and to subsequently devise strategic recommendations. In its March 2015 report on the Ferguson Police Department, the Department of Justice found that although only 67% of the population of Ferguson was black, 85% of people pulled over by police in Ferguson were black, as were 93 percent of those arrested and 90 percent of those given citations by the police.

A 2020 study in the journal Nature that analyzed 100 million traffic stops found that "black drivers were less likely to be stopped after sunset, when a ‘veil of darkness’ masks one’s race, suggesting bias in stop decisions", "the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was lower than that for searching white drivers", and "legalization of recreational marijuana reduced the number of searches of white, black and Hispanic drivers—but the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers was still lower than that for white drivers post-legalization". The authors concluded that "police stops and search decisions suffer from persistent racial bias and point to the value of policy interventions to mitigate these disparities".

Racial profiling in retail

Shopping forms one major avenue for racial profiling. General discrimination devalues the experience of shopping, arguably raising the costs and reducing the rewards derived from consumption for the individual. When a store's sales staff appears hesitant to serve black shoppers or suspects that they are prospective shoplifters, the act of shopping no longer becomes a form of leisure.

Racial profiling in retail was prominent enough in 2001 that psychology researchers such as Jerome D. Williams coined the term "shopping while black", which describes the experience of being denied service or given poor service because one is black. Commonly, "shopping while black" involves, but is not limited to, a black or non-white customer being followed around and/or closely monitored by a clerk or guard who suspects he or she may steal, based on the color of their skin. It can also involve being denied store access, being refused service, use of ethnic slurs, being searched, being asked for extra forms of identification, having purchases limited, being required to have a higher credit limit than other customers, being charged a higher price, or being asked more or more rigorous questions on applications. These negative shopping experiences can directly contribute to the decline of shopping in stores as individuals will come to prefer to shop online, avoiding interactions that are deemed degrading, embarrassing, and highly offensive.

Public opinion

Perceptions of race and safety

In a particular study, Higgins, Gabbidon, and Vito studied the relationship between public opinion on racial profiling in conjunction with their viewpoint of race relations and their perceived awareness of safety. It was found that race relations had a statistical correlation with the legitimacy of racial profiling. Specifically, results showed that those who believed that racial profiling was widespread and that racial tension would never be fixed were more likely to be opposed to racial profiling than those who did not believe racial profiling was as widespread or that racial tensions would be fixed eventually. On the other hand, in reference to the perception of safety, the research concluded that one's perception of safety had no influence on public opinion of racial profiling. Higgins, Gabbidon, and Vito acknowledge that this may not have been the case immediately after 9/11, but state that any support of racial profiling based on safety was "short-lived".

Influence of religious affiliation

One particular study focused on individuals who self-identified as religiously affiliated and their relationship with racial profiling. By using national survey data from October 2001, researcher Phillip H. Kim studied which individuals were more likely to support racial profiling. The research concludes that individuals that identified themselves as either Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant showed higher statistical numbers that illustrated support for racial profiling in comparison to individuals who identified themselves as non-religious.

Contexts of terrorism and crime

After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, according to Johnson, a new debate concerning the appropriateness of racial profiling in the context of terrorism took place. According to Johnson, prior to the September 11, 2001 attacks the debate on racial profiling within the public targeted primarily African-Americans and Latino Americans with enforced policing on crime and drugs. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon changed the focus of the racial profiling debate from street crime to terrorism. According to a June 4–5, 2002 FOX News/Opinion Dynamics Poll, 54% of Americans approved of using "racial profiling to screen Arab male airline passengers." A 2002 survey by Public Agenda tracked the attitudes toward the racial profiling of Blacks and people of Middle Eastern descent. In this survey, 52% of Americans said there was "no excuse" for law enforcement to look at African Americans with greater suspicion and scrutiny because they believe they are more likely to commit crimes, but only 21% said there was "no excuse" for extra scrutiny of Middle Eastern people.

However, using data from an internet survey based experiment performed in 2006 on a random sample of 574 adult university students, a study was conducted that examined public approval for the use of racial profiling to prevent crime and terrorism. It was found that approximately one third of students approved the use of racial profiling in general. Furthermore, it was found that students were equally likely to approve of the use of racial profiling to prevent crime as to prevent terrorism-33% and 35.8% respectively. The survey also asked respondents whether they would approve of racial profiling across different investigative contexts.

The data showed that 23.8% of people approved of law enforcement using racial profiling as a means to stop and question someone in a terrorism context while 29.9% of people approved of racial profiling in a crime context for the same situation. It was found that 25.3% of people approved of law enforcement using racial profiling as a means to search someone's bags or packages in a terrorism context while 33.5% of people approved of racial profiling in a crime context for the same situation. It was also found that 16.3% of people approved of law enforcement wire tapping a person's phone based upon racial profiling in the context of terrorism while 21.4% of people approved of racial profiling in a crime context for the same situation. It was also found that 14.6% of people approved of law enforcement searching someone's home based upon racial profiling in a terrorism context while 18.2% of people approved of racial profiling in a crime context for the same situation.

The study also found that white students were more likely to approve of racial profiling to prevent terrorism than nonwhite students. However, it was found that white students and nonwhite students held the same views about racial profiling in the context of crime. It was also found that foreign born students were less likely to approve of racial profiling to prevent terrorism than non-foreign born students while both groups shared similar views on racial profiling in the context of crime.