| Middle English | |

|---|---|

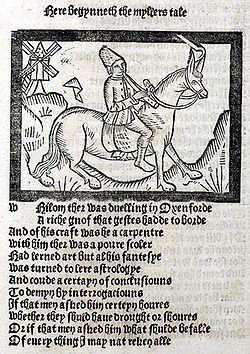

A page from Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales | |

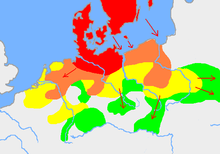

| Region | England, some parts of Wales, south east Scotland and Scottish burghs, to some extent Ireland |

| Era | developed into Early Modern English, Scots, and Yola and Fingallian in Ireland by the 16th century |

Early form | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | enm |

| ISO 639-3 | enm |

| ISO 639-6 | meng |

| Glottolog | midd1317 |

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) was a form of the English language spoken after the Norman conquest (1066) until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English period. Scholarly opinion varies, but the Oxford English Dictionary specifies the period when Middle English was spoken as being from 1150 to 1500. This stage of the development of the English language roughly followed the High to the Late Middle Ages.

Middle English saw significant changes to its vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and orthography. Writing conventions during the Middle English period varied widely. Examples of writing from this period that have survived show extensive regional variation. The more standardized Old English language became fragmented, localized, and was, for the most part, being improvised. By the end of the period (about 1470) and aided by the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439, a standard based on the London dialects (Chancery Standard) had become established. This largely formed the basis for Modern English spelling, although pronunciation has changed considerably since that time. Middle English was succeeded in England by Early Modern English, which lasted until about 1650. Scots developed concurrently from a variant of the Northumbrian dialect (prevalent in northern England and spoken in southeast Scotland).

During the Middle English period, many Old English grammatical features either became simplified or disappeared altogether. Noun, adjective and verb inflections were simplified by the reduction (and eventual elimination) of most grammatical case distinctions. Middle English also saw considerable adoption of Norman vocabulary, especially in the areas of politics, law, the arts, and religion, as well as poetic and emotive diction. Conventional English vocabulary remained primarily Germanic in its sources, with Old Norse influences becoming more apparent. Significant changes in pronunciation took place, particularly involving long vowels and diphthongs, which in the later Middle English period began to undergo the Great Vowel Shift.

Little survives of early Middle English literature, due in part to Norman domination and the prestige that came with writing in French rather than English. During the 14th century, a new style of literature emerged with the works of writers including John Wycliffe and Geoffrey Chaucer, whose Canterbury Tales remains the most studied and read work of the period.

History

Transition from Old English

The transition from Late Old English to Early Middle English occurred at some time during the 12th century.

The influence of Old Norse aided the development of English from a synthetic language with relatively free word order, to a more analytic or isolating language with a more strict word order. Both Old English and Old Norse (as well as the descendants of the latter, Faroese and Icelandic) were synthetic languages with complicated inflections. The eagerness of Vikings in the Danelaw to communicate with their Anglo-Saxon neighbours resulted in the erosion of inflection in both languages. Old Norse may have had a more profound impact on Middle and Modern English development than any other language. Simeon Potter notes: "No less far-reaching was the influence of Scandinavian upon the inflexional endings of English in hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms which gradually spread from north to south.".

Viking influence on Old English is most apparent in the more indispensable elements of the language. Pronouns, modals, comparatives, pronominal adverbs (like "hence" and "together"), conjunctions and prepositions show the most marked Danish influence. The best evidence of Scandinavian influence appears in extensive word borrowings, yet no texts exist in either Scandinavia or in Northern England from this period to give certain evidence of an influence on syntax. The change to Old English from Old Norse was substantive, pervasive, and of a democratic character. Like close cousins, Old Norse and Old English resembled each other, and with some words in common, they roughly understood each other; in time the inflections melted away and the analytic pattern emerged. It is most "important to recognise that in many words the English and Scandinavian language differed chiefly in their inflectional elements. The body of the word was so nearly the same in the two languages that only the endings would put obstacles in the way of mutual understanding. In the mixed population which existed in the Danelaw these endings must have led to much confusion, tending gradually to become obscured and finally lost." This blending of peoples and languages resulted in "simplifying English grammar."

While the influence of Scandinavian languages was strongest in the dialects of the Danelaw region and Scotland, words in the spoken language emerge in the 10th and 11th centuries near the transition from the Old to Middle English. Influence on the written language only appeared at the beginning of the 13th century, likely because of a scarcity of literary texts from an earlier date.

The Norman conquest of England in 1066 saw the replacement of the top levels of the English-speaking political and ecclesiastical hierarchies by Norman rulers who spoke a dialect of Old French known as Old Norman, which developed in England into Anglo-Norman. The use of Norman as the preferred language of literature and polite discourse fundamentally altered the role of Old English in education and administration, even though many Normans of this period were illiterate and depended on the clergy for written communication and record-keeping. A significant number of words of Norman origin began to appear in the English language alongside native English words of similar meaning, giving rise to such Modern English synonyms as pig/pork, chicken/poultry, calf/veal, cow/beef, sheep/mutton, wood/forest, house/mansion, worthy/valuable, bold/courageous, freedom/liberty, sight/vision, eat/dine.

The role of Anglo-Norman as the language of government and law can be seen in the abundance of Modern English words for the mechanisms of government that are derived from Anglo-Norman: court, judge, jury, appeal, parliament. There are also many Norman-derived terms relating to the chivalric cultures that arose in the 12th century; an era of feudalism, seigneurialism and crusading.

Words were often taken from Latin, usually through French transmission. This gave rise to various synonyms including kingly (inherited from Old English), royal (from French, which inherited it from Vulgar Latin), and regal (from French, which borrowed it from classical Latin). Later French appropriations were derived from standard, rather than Norman, French. Examples of resultant cognate pairs include the words warden (from Norman), and guardian (from later French; both share a common Germanic ancestor).

The end of Anglo-Saxon rule did not result in immediate changes to the language. The general population would have spoken the same dialects as they had before the Conquest. Once the writing of Old English came to an end, Middle English had no standard language, only dialects that derived from the dialects of the same regions in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Early Middle English

Early Middle English (1150–1300) has a largely Anglo-Saxon vocabulary (with many Norse borrowings in the northern parts of the country), but a greatly simplified inflectional system. The grammatical relations that were expressed in Old English by the dative and instrumental cases are replaced in Early Middle English with prepositional constructions. The Old English genitive -es survives in the -'s of the modern English possessive, but most of the other case endings disappeared in the Early Middle English period, including most of the roughly one dozen forms of the definite article ("the"). The dual personal pronouns (denoting exactly two) also disappeared from English during this period.

Gradually, the wealthy and the government Anglicised again, although Norman (and subsequently French) remained the dominant language of literature and law until the 14th century, even after the loss of the majority of the continental possessions of the English monarchy. The loss of case endings was part of a general trend from inflections to fixed word order that also occurred in other Germanic languages (though more slowly and to a lesser extent), and therefore it cannot be attributed simply to the influence of French-speaking sections of the population: English did, after all, remain the vernacular. It is also argued that Norse immigrants to England had a great impact on the loss of inflectional endings in Middle English. One argument is that, although Norse- and English-speakers were somewhat comprehensible to each other due to similar morphology, the Norse-speakers' inability to reproduce the ending sounds of English words influenced Middle English's loss of inflectional endings.

Important texts for the reconstruction of the evolution of Middle English out of Old English are the Peterborough Chronicle, which continued to be compiled up to 1154; the Ormulum, a biblical commentary probably composed in Lincolnshire in the second half of the 12th century, incorporating a unique phonetic spelling system; and the Ancrene Wisse and the Katherine Group, religious texts written for anchoresses, apparently in the West Midlands in the early 13th century. The language found in the last two works is sometimes called the AB language.

More literary sources of the 12th and 13th centuries include Layamon's Brut and The Owl and the Nightingale.

Some scholars have defined "Early Middle English" as encompassing English texts up to 1350. This longer time frame would extend the corpus to include many Middle English Romances (especially those of the Auchinleck manuscript c. 1330).

14th century

From around the early 14th century, there was significant migration into London, particularly from the counties of the East Midlands, and a new prestige London dialect began to develop, based chiefly on the speech of the East Midlands, but also influenced by that of other regions. The writing of this period, however, continues to reflect a variety of regional forms of English. The Ayenbite of Inwyt, a translation of a French confessional prose work, completed in 1340, is written in a Kentish dialect. The best known writer of Middle English, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote in the second half of the 14th century in the emerging London dialect, although he also portrays some of his characters as speaking in northern dialects, as in the "Reeve's Tale".

In the English-speaking areas of lowland Scotland, an independent standard was developing, based on the Northumbrian dialect. This would develop into what came to be known as the Scots language.

A large number of terms for abstract concepts were adopted directly from scholastic philosophical Latin (rather than via French). Examples are "absolute", "act", "demonstration", "probable".

Late Middle English

The Chancery Standard of written English emerged c. 1430 in official documents that, since the Norman Conquest, had normally been written in French. Like Chaucer's work, this new standard was based on the East-Midlands-influenced speech of London. Clerks using this standard were usually familiar with French and Latin, influencing the forms they chose. The Chancery Standard, which was adopted slowly, was used in England by bureaucrats for most official purposes, excluding those of the Church and legalities, which used Latin and Law French (and some Latin), respectively.

The Chancery Standard's influence on later forms of written English is disputed, but it did undoubtedly provide the core around which Early Modern English formed. Early Modern English emerged with the help of William Caxton's printing press, developed during the 1470s. The press stabilized English through a push towards standardization, led by Chancery Standard enthusiast and writer Richard Pynson. Early Modern English began in the 1540s after the printing and wide distribution of the English Bible and Prayer Book, which made the new standard of English publicly recognizable, and lasted until about 1650.

Phonology

The main changes between the Old English sound system and that of Middle English include:

- Emergence of the voiced fricatives /v/, /ð/, /z/ as separate phonemes, rather than mere allophones of the corresponding voiceless fricatives.

- Reduction of the Old English diphthongs to monophthongs, and the emergence of new diphthongs due to vowel breaking in certain positions, change of Old English post-vocalic /j/, /w/ (sometimes resulting from the [ɣ] allophone of /ɡ/) to offglides, and borrowing from French.

- Merging of Old English /æ/ and /ɑ/ into a single vowel /a/.

- Raising of the long vowel /æː/ to /ɛː/.

- Rounding of /ɑː/ to /ɔː/ in the southern dialects.

- Unrounding of the front rounded vowels in most dialects.

- Lengthening of vowels in open syllables (and in certain other positions). The resultant long vowels (and other pre-existing long vowels) subsequently underwent changes of quality in the Great Vowel Shift, which began during the later Middle English period.

- Loss of gemination (double consonants came to be pronounced as single ones).

- Loss of weak final vowels (schwa, written ⟨e⟩). By Chaucer's time this vowel was silent in normal speech, although it was normally pronounced in verse as the meter required (much as occurs in modern French). Also, non-final unstressed ⟨e⟩ was dropped when adjacent to only a single consonant on either side if there was another short ⟨e⟩ in an adjoining syllable. Thus, every began to be pronounced as evry, and palmeres as palmers.

The combination of the last three processes listed above led to the spelling conventions associated with silent ⟨e⟩ and doubled consonants (see under Orthography, below).

Morphology

Nouns

Middle English retains only two distinct noun-ending patterns from the more complex system of inflection in Old English:

| Nouns | Strong nouns

(O.E. o, n, wo and u stem) |

Weak nouns

(O.E. a, i, root, nd, r, z and h stem) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | -(e) | -es | -e | -en |

| Accusative | -en | |||

| Genitive | -es | -e(ne) | ||

| Dative | -e | -e(s) | ||

Some nouns of the strong type have an -e in the nominative/accusative singular, like the weak declension, but otherwise strong endings. Often these are the same nouns that had an -e in the nominative/accusative singular of Old English (they, in turn, were inherited from Proto-Germanic ja-stem and i-stem nouns).

The distinct dative case was lost in early Middle English. The genitive survived, however, but by the end of the Middle English period, only the strong -'s ending (variously spelt) was in use. Some formerly feminine nouns, as well as some weak nouns, continued to make their genitive forms with -e or no ending (e.g. fole hoves, horses' hoves), and nouns of relationship ending in -er frequently have no genitive ending (e.g. fader bone, "father's bane").

The strong -(e)s plural form has survived into Modern English. The weak -(e)n form is now rare and used only in oxen and, as part of a double plural, in children and brethren. Some dialects still have forms such as eyen (for eyes), shoon (for shoes), hosen (for hose(s)), kine (for cows), and been (for bees).

Grammatical gender survived to a limited extent in early Middle English, before being replaced by natural gender in the course of the Middle English period. Grammatical gender was indicated by agreement of articles and pronouns, i.e. þo ule ("the-feminine owl") or using the pronoun he to refer to masculine nouns such as helm ("helmet"), or phrases such as scaft stærcne (strong shaft) with the masculine accusative adjective ending -ne.

Adjectives

Single syllable adjectives add -e when modifying a noun in the plural and when used after the definite article (þe), after a demonstrative (þis, þat), after a possessive pronoun (e.g. hir, our), or with a name or in a form of address. This derives from the Old English "weak" declension of adjectives. This inflexion continued to be used in writing even after final -e had ceased to be pronounced. In earlier texts, multi-syllable adjectives also receive a final -e in these situations, but this occurs less regularly in later Middle English texts. Otherwise adjectives have no ending, and adjectives already ending in -e etymologically receive no ending as well.

Earlier texts sometimes inflect adjectives for case as well. Layamon's Brut inflects adjectives for the masculine accusative, genitive, and dative, the feminine dative, and the plural genitive. The Owl and the Nightingale adds a final -e to all adjectives not in the nominative, here only inflecting adjectives in the weak declension (as described above).

Comparatives and superlatives are usually formed by adding -er and -est. Adjectives with long vowels sometimes shorten these vowels in the comparative and superlative, e.g. greet (great) gretter (greater). Adjectives ending in -ly or -lich form comparatives either with -lier, -liest or -loker, -lokest. A few adjectives also display Germanic umlaut in their comparatives and superlatives, such as long, lenger. Other irregular forms are mostly the same as in modern English.

Pronouns

Middle English personal pronouns were mostly developed from those of Old English, with the exception of the third-person plural, a borrowing from Old Norse (the original Old English form clashed with the third person singular and was eventually dropped). Also, the nominative form of the feminine third-person singular was replaced by a form of the demonstrative that developed into sche (modern she), but the alternative heyr remained in some areas for a long time.

As with nouns, there was some inflectional simplification (the distinct Old English dual forms were lost), but pronouns, unlike nouns, retained distinct nominative and accusative forms. Third-person pronouns also retained a distinction between accusative and dative forms, but that was gradually lost: the masculine hine was replaced by him south of the Thames by the early 14th century, and the neuter dative him was ousted by it in most dialects by the 15th.

The following table shows some of the various Middle English pronouns. Many other variations are noted in Middle English sources because of differences in spellings and pronunciations at different times and in different dialects.

| Personal pronouns | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | ||||||

| Nominative | ic, ich, I | we | þeou, þ(o)u, tu | ye | he | hit | s(c)he(o) | he(o)/ þei |

| Accusative | mi | (o)us | þe | eow, eou, yow, gu, you | hine | heo, his, hi(r)e | his/ þem | |

| Dative | him | him | heo(m), þo/ þem | |||||

| Possessive | min(en) | (o)ure, ures, ure(n) | þi, ti | eower, yower, gur, eour | his, hes | his | heo(re), hio, hire | he(o)re/ þeir |

| Genitive | min, mire, minre | oures | þin, þyn | youres | his | |||

| Reflexive | min one, mi selven | us self, ous-silve | þeself, þi selven | you-self/ you-selve | him-selven | hit-sulve | heo-seolf | þam-selve/ þem-selve |

Verbs

As a general rule, the indicative first person singular of verbs in the present tense ends in -e (ich here, 'I hear'), the second person in -(e)st (þou spekest, 'thou speakest'), and the third person in -eþ (he comeþ, 'he cometh/he comes'). (þ (the letter 'thorn') is pronounced like the unvoiced th in "think", but, under certain circumstances, it may be like the voiced th in "that"). The following table illustrates a typical conjugation pattern:

| Verbs inflection | Infinitive | Present | Past | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participle | Singular | Plural | Participle | Singular | Plural | ||||||

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | ||||||

| Regular verbs | |||||||||||

| Strong | -en | -ende, -ynge | -e | -est | -eþ (-es) | -en (-es, -eþ) | i- -en | - | -e (-est) | - | -en |

| Weak | -ed | -ede | -edest | -ede | -eden | ||||||

| Irregular verbs | |||||||||||

| Been "be" | been | beende, beynge | am | art | is | aren | ibeen | was | wast | was | weren |

| be | bist | biþ | beth, been | were | |||||||

| Cunnen "can" | cunnen | cunnende, cunnynge | can | canst | can | cunnen | cunned, coud | coude, couthe | coudest, couthest | coude, couthe | couden, couthen |

| Don "do" | don | doende, doynge | do | dost | doþ | doþ, don | idon | didde | didst | didde | didden |

| Douen "be good for" | douen | douende, douynge | deigh | deight | deigh | douen | idought | dought | doughtest | dought | doughten |

| Durren "dare" | durren | durrende, durrynge | dar | darst | dar | durren | durst, dirst | durst | durstest | durst | dursten |

| Gon "go" | gon | goende, goynge | go | gost | goþ | goþ, gon | igon(gen) | wend, yede, yode | wendest, yedest, yodest | wende, yede, yode | wenden, yeden, yoden |

| Haven "have" | haven | havende, havynge | have | hast | haþ | haven | ihad | hadde | haddest | hadde | hadden |

| Moten "must" | - | - | mot | must | mot | moten | - | muste | mustest | muste | musten |

| Mowen "may" | mowen | mowende, mowynge | may | myghst | may | mowen | imought | mighte | mightest | mighte | mighten |

| Owen "owe, ought" | owen | owende, owynge | owe | owest | owe | owen | iowen | owed | ought | owed | ought |

| Schulen "should" | - | - | schal | schalt | schal | schulen | - | scholde | scholdest | scholde | scholde |

| Þurven "need" | - | - | þarf | þarst | þarf | þurven | - | þurft | þurst | þurft | þurften |

| Willen "want" | willen | willende, willynge | will | wilt | will | wollen | - | wolde | woldest | wolde | wolden |

| Witen "know" | witen | witende, witynge | woot | woost | woot | witen | iwiten | wiste | wistest | wiste | wisten |

Plural forms vary strongly by dialect, with Southern dialects preserving the Old English -eþ, Midland dialects showing -en from about 1200 and Northern forms using -es in the third person singular as well as the plural.

The past tense of weak verbs is formed by adding an -ed(e), -d(e) or -t(e) ending. The past-tense forms, without their personal endings, also serve as past participles with past-participle prefixes derived from Old English: i-, y- and sometimes bi-.

Strong verbs, by contrast, form their past tense by changing their stem vowel (binden becomes bound, a process called apophony), as in Modern English.

Orthography

With the discontinuation of the Late West Saxon standard used for the writing of Old English in the period prior to the Norman Conquest, Middle English came to be written in a wide variety of scribal forms, reflecting different regional dialects and orthographic conventions. Later in the Middle English period, however, and particularly with the development of the Chancery Standard in the 15th century, orthography became relatively standardised in a form based on the East Midlands-influenced speech of London. Spelling at the time was mostly quite regular (there was a fairly consistent correspondence between letters and sounds). The irregularity of present-day English orthography is largely due to pronunciation changes that have taken place over the Early Modern English and Modern English eras.

Middle English generally did not have silent letters. For example, knight was pronounced [ˈkniçt] (with both the ⟨k⟩ and the ⟨gh⟩ pronounced, the latter sounding as the ⟨ch⟩ in German knecht). The major exception was the silent ⟨e⟩ – originally pronounced, but lost in normal speech by Chaucer's time. This letter, however, came to indicate a lengthened – and later also modified – pronunciation of a preceding vowel. For example, in name, originally pronounced as two syllables, the /a/ in the first syllable (originally an open syllable) lengthened, the final weak vowel was later dropped, and the remaining long vowel was modified in the Great Vowel Shift (for these sound changes, see under Phonology, above). The final ⟨e⟩, now silent, thus became the indicator of the longer and changed pronunciation of ⟨a⟩. In fact vowels could have this lengthened and modified pronunciation in various positions, particularly before a single consonant letter and another vowel, or before certain pairs of consonants.

A related convention involved the doubling of consonant letters to show that the preceding vowel was not to be lengthened. In some cases the double consonant represented a sound that was (or had previously been) geminated, i.e. had genuinely been "doubled" (and would thus have regularly blocked the lengthening of the preceding vowel). In other cases, by analogy, the consonant was written double merely to indicate the lack of lengthening.

Alphabet

The basic Old English Latin alphabet had consisted of 20 standard letters plus four additional letters: ash ⟨æ⟩, eth ⟨ð⟩, thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨ƿ⟩. There was not yet a distinct j, v or w, and Old English scribes did not generally use k, q or z.

Ash was no longer required in Middle English, as the Old English vowel /æ/ that it represented had merged into /a/. The symbol nonetheless came to be used as a ligature for the digraph ⟨ae⟩ in many words of Greek or Latin origin, as did /œ/ for ⟨oe⟩.

Eth and thorn both represented /θ/ or its allophone /ð/

in Old English. Eth fell out of use during the 13th century and was

replaced by thorn. Thorn mostly fell out of use during the 14th century,

and was replaced by ⟨th⟩. Anachronistic usage of the scribal abbreviation ![]() (þe, i.e. "the") has led to the modern mispronunciation of thorn as ⟨y⟩ in this context; see ye olde.

(þe, i.e. "the") has led to the modern mispronunciation of thorn as ⟨y⟩ in this context; see ye olde.

Wynn, which represented the phoneme /w/, was replaced by ⟨w⟩ during the 13th century. Due to its similarity to the letter ⟨p⟩, it is mostly represented by ⟨w⟩ in modern editions of Old and Middle English texts even when the manuscript has wynn.

Under Norman influence, the continental Carolingian minuscule replaced the insular script that had been used for Old English. However, because of the significant difference in appearance between the old insular g and the Carolingian g (modern g), the former continued in use as a separate letter, known as yogh, written ⟨ȝ⟩. This was adopted for use to represent a variety of sounds: [ɣ], [j], [dʒ], [x], [ç], while the Carolingian g was normally used for [g]. Instances of yogh were eventually replaced by ⟨j⟩ or ⟨y⟩, and by ⟨gh⟩ in words like night and laugh. In Middle Scots yogh became indistinguishable from cursive z, and printers tended to use ⟨z⟩ when yogh was not available in their fonts; this led to new spellings (often giving rise to new pronunciations), as in McKenzie, where the ⟨z⟩ replaced a yogh which had the pronunciation /j/.

Under continental influence, the letters ⟨k⟩, ⟨q⟩ and ⟨z⟩, which had not normally been used by Old English scribes, came to be commonly used in the writing of Middle English. Also the newer Latin letter ⟨w⟩ was introduced (replacing wynn). The distinct letter forms ⟨v⟩ and ⟨u⟩ came into use, but were still used interchangeably; the same applies to ⟨j⟩ and ⟨i⟩. (For example, spellings such as wijf and paradijs for wife and paradise can be found in Middle English.)

The consonantal ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ was sometimes used to transliterate the Hebrew letter yodh, representing the palatal approximant sound /j/ (and transliterated in Greek by iota and in Latin by ⟨i⟩); words like Jerusalem, Joseph, etc. would have originally followed the Latin pronunciation beginning with /j/, that is, the sound of ⟨y⟩ in yes. In some words, however, notably from Old French, ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ was used for the affricate consonant /dʒ/, as in joie (modern "joy"), used in Wycliffe's Bible. This was similar to the geminate sound [ddʒ], which had been represented as ⟨cg⟩ in Old English. By the time of Modern English, the sound came to be written as ⟨j⟩/⟨i⟩ at the start of words (like joy), and usually as ⟨dg⟩ elsewhere (as in bridge). It could also be written, mainly in French loanwords, as ⟨g⟩, with the adoption of the soft G convention (age, page, etc.)

Other symbols

Many scribal abbreviations were also used. It was common for the Lollards to abbreviate the name of Jesus (as in Latin manuscripts) to ihc. The letters ⟨n⟩ and ⟨m⟩ were often omitted and indicated by a macron above an adjacent letter, so for example in could be written as ī. A thorn with a superscript ⟨t⟩ or ⟨e⟩ could be used for that and the; the thorn here resembled a ⟨Y⟩, giving rise to the ye of "Ye Olde". Various forms of the ampersand replaced the word and.

Numbers were still always written using Roman numerals, except for some rare occurrences of Arabic numerals during the 15th century.

Letter-to-sound correspondences

Although Middle English spelling was never fully standardised, the following table shows the pronunciations most usually represented by particular letters and digraphs towards the end of the Middle English period, using the notation given in the article on Middle English phonology. As explained above, single vowel letters had alternative pronunciations depending on whether they were in a position where their sounds had been subject to lengthening. Long vowel pronunciations were in flux due to the beginnings of the Great Vowel Shift.

| Symbol | Description and notes |

|---|---|

| a | /a/, or in lengthened positions /aː/, becoming [æː] by about 1500. Sometimes /au/ before ⟨l⟩ or nasals (see Late Middle English diphthongs). |

| ai, ay | /ai/ (alternatively denoted by /ɛi/; see vein–vain merger). |

| au, aw | /au/ |

| b | /b/, but in later Middle English became silent in words ending -mb (while some words that never had a /b/ sound came to be spelt -mb by analogy; see reduction of /mb/). |

| c | /k/, but /s/ (earlier /ts/) before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨y⟩ (see C and hard and soft C for details). |

| ch | /tʃ/ |

| ck | /k/, replaced earlier ⟨kk⟩ as the doubled form of ⟨k⟩ (for the phenomenon of doubling, see above). |

| d | /d/ |

| e | /e/, or in lengthened positions /eː/ or sometimes /ɛː/ (see ee). For silent ⟨e⟩, see above. |

| ea | Rare, for /ɛː/ (see ee). |

| ee | /eː/, becoming [iː] by about 1500; or /ɛː/, becoming [eː] by about 1500. In Early Modern English the latter vowel came to be commonly written ⟨ea⟩. The two vowels later merged. |

| ei, ey | Sometimes the same as ⟨ai⟩; sometimes /ɛː/ or /eː/ (see also fleece merger). |

| ew | Either /ɛu/ or /iu/ (see Late Middle English diphthongs; these later merged). |

| f | /f/ |

| g | /ɡ/, or /dʒ/ before ⟨e⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨y⟩ (see ⟨g⟩ for details). The ⟨g⟩ in initial gn- was still pronounced. |

| gh | [ç] or [x], post-vowel allophones of /h/ (this was formerly one of the uses of yogh). The ⟨gh⟩ is often retained in Chancery spellings even though the sound was starting to be lost. |

| h | /h/ (except for the allophones for which ⟨gh⟩ was used). Also used in several digraphs (⟨ch⟩, ⟨th⟩, etc.). In some French loanwords, such as horrible, the ⟨h⟩ was silent. |

| i, j | As a vowel, /i/, or in lengthened positions /iː/, which had started to be diphthongised by about 1500. As a consonant, /dʒ/ ( (corresponding to modern ⟨j⟩); see above). |

| ie | Used sometimes for /ɛː/ (see ee). |

| k | /k/, used particularly in positions where ⟨c⟩ would be softened. Also used in ⟨kn⟩ at the start of words; here both consonants were still pronounced. |

| l | /l/ |

| m | /m/ |

| n | /n/, including its allophone [ŋ] (before /k/, /g/). |

| o | /o/, or in lengthened positions /ɔː/ or sometimes /oː/ (see oo). Sometimes /u/, as in sone (modern son); the ⟨o⟩ spelling was often used rather than ⟨u⟩ when adjacent to i, m, n, v, w for legibility, i.e. to avoid a succession of vertical strokes. |

| oa | Rare, for /ɔː/ (became commonly used in Early Modern English). |

| oi, oy | /ɔi/ or /ui/ (see Late Middle English diphthongs; these later merged). |

| oo | /oː/, becoming [uː] by about 1500; or /ɔː/. |

| ou, ow | Either /uː/, which had started to be diphthongised by about 1500, or /ɔu/. |

| p | /p/ |

| qu | /kw/ |

| r | /r/ |

| s | /s/, sometimes /z/ (formerly [z] was an allophone of /s/). Also appeared as ſ (long s). |

| sch, sh | /ʃ/ |

| t | /t/ |

| th | /θ/ or /ð/ (which had previously been allophones of a single phoneme), replacing earlier eth and thorn, although thorn was still sometimes used. |

| u, v | Used interchangeably. As a consonant, /v/. As a vowel, /u/, or /iu/ in "lengthened" positions (although it had generally not gone through the same lengthening process as other vowels – see history of /iu/). |

| w | /w/ (replaced Old English wynn). |

| wh | /hw/ (see English ⟨wh⟩). |

| x | /ks/ |

| y | As a consonant, /j/ (earlier this was one of the uses of yogh). Sometimes also /g/. As a vowel, the same as ⟨i⟩, where ⟨y⟩ is often preferred beside letters with downstrokes. |

| z | /z/ (in Scotland sometimes used as a substitute for yogh; see above). |

Sample texts

Most of the following Modern English translations are poetic sense-for-sense translations, not word-for-word translations.

Ormulum, 12th century

This passage explains the background to the Nativity(3494–501):

| Forrþrihht anan se time commþatt ure Drihhtin wolldeben borenn i þiss middellærdforr all mannkinne nedehe chæs himm sone kinnessmennall swillke summ he wolldeand whær he wollde borenn benhe chæs all att hiss wille. | Forthwith when the time camethat our Lord wantedbe born in this earthfor all mankind sake,He chose kinsmen for Himself,all just as he wanted,and where He would be bornHe chose exactly as He wished. |

Epitaph of John the smyth, died 1371

An epitaph from a monumental brass in an Oxfordshire parish church:

| Original text | Translation by Patricia Utechin |

|---|---|

| man com & se how schal alle dede li: wen þow comes bad & barenoth hab ven ve awaẏ fare: All ẏs wermēs þt ve for care:—bot þt ve do for godẏs luf ve haue nothyng yare:hundyr þis graue lẏs John þe smẏth god yif his soule heuen grit | Man, come and see how all dead men shall lie: when that comes bad and bare,we have nothing when we away fare: all that we care for is worms:—except for that which we do for God's sake, we have nothing ready:under this grave lies John the smith, God give his soul heavenly peace |

Wycliffe's Bible, 1384

From the Wycliffe's Bible, (1384):

| First version | Second version | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesu made iorney by citees and castelis, prechinge and euangelysinge þe rewme of God, 2and twelue wiþ him; and summe wymmen þat weren heelid of wickide spiritis and syknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Mawdeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis wenten 3 out, and Jone, þe wyf of Chuse, procuratour of Eroude, and Susanne, and manye oþere, whiche mynystriden to him of her riches. | 1And it was don aftirward, and Jhesus made iourney bi citees and castels, prechynge and euangelisynge þe rewme of 2God, and twelue wiþ hym; and sum wymmen þat weren heelid of wickid spiritis and sijknessis, Marie, þat is clepid Maudeleyn, of whom seuene deuelis 3wenten out, and Joone, þe wijf of Chuse, þe procuratoure of Eroude, and Susanne, and many oþir, þat mynystriden to hym of her ritchesse. | 1And it happened afterwards, that Jesus made a journey through cities and settlements, preaching and evangelising the realm of 2God: and with him The Twelve; and some women that were healed of wicked spirits and sicknesses; Mary who is called Magdalen, from whom 3seven devils went out; and Joanna the wife of Chuza, the steward of Herod; and Susanna, and many others, who administered to Him out of their own means. |

Chaucer, 1390s

The following is the very beginning of the General Prologue from The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. The text was written in a dialect associated with London and spellings associated with the then-emergent Chancery Standard.

| Original in Middle English | Word-for-word translation into Modern English |

|---|---|

| Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote | When [that] April with his showers sweet |

| The droȝte of March hath perced to the roote | The drought of March has pierced to the root |

| And bathed every veyne in swich licour, | And bathed every vein in such liquor (sap), |

| Of which vertu engendred is the flour; | From which goodness is engendered the flower; |

| Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth | When Zephyrus even with his sweet breath |

| Inspired hath in every holt and heeth | Inspired has in every holt and heath |

| The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne | The tender crops; and the young sun |

| Hath in the Ram his halfe cours yronne, | Has in the Ram his half-course run, |

| And smale foweles maken melodye, | And small birds make melodies, |

| That slepen al the nyght with open ye | That sleep all night with open eyes |

| (So priketh hem Nature in hir corages); | (So Nature prompts them in their boldness); |

| Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages | Then folk long to go on pilgrimages. |

| And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes | And pilgrims (palmers) [for] to seek new strands |

| To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; | To far-off shrines (hallows), respected in sundry lands; |

| And specially from every shires ende | And specially from every shire's end |

| Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, | Of England, to Canterbury they wend, |

| The hooly blisful martir for to seke | The holy blissful martyr [for] to seek, |

| That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke. | That has helped them, when [that] they were sick. |

Translation into Modern U.K. English prose: When April with its sweet showers has drenched March's drought to the roots, filling every capillary with nourishing sap prompting the flowers to grow, and when the breeze (Zephyrus) with his sweet breath has coaxed the tender plants to sprout in every wood and dale, as the springtime sun passes halfway through the sign of Aries, and small birds that sleep all night with half-open eyes chirp melodies, their spirits thus aroused by Nature; it is at these times that people desire to go on pilgrimages and pilgrims (palmers) seek new shores and distant shrines venerated in other places. Particularly they go to Canterbury, from every county of England, in order to visit the holy blessed martyr, who has helped them when they were unwell.

Gower, 1390

The following is the beginning of the Prologue from Confessio Amantis by John Gower.

| Original in Middle English | Near word-for-word translation into Modern English: | Translation into Modern English: (by Richard Brodie) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Translation in Modern English: (by J. Dow)

Of those who wrote before we were born, books survive,

So we are taught what was written by them when they were alive. So it's good that we, in our times here on earth, write of new matters – Following the example of our forefathers – So that, in such a way, we may leave our knowledge to the world after we are dead and gone. But it's said, and it is true, that if one only reads of wisdom all day long It often dulls one's brains. So, if it's alright with you, I'll take the middle route and write a book between the two – Somewhat of amusement, and somewhat of fact.

In that way, somebody might, more or less, like that.