The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear weapon, The Gadget at the Trinity test in New Mexico, on 16 July 1945, during World War II. Although nuclear chain reactions had been hypothesized in 1933 and the first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction (Chicago Pile-1) had taken place in December 1942, the Trinity test and the ensuing bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended World War II represented the first large-scale use of nuclear technology and ushered in profound changes in sociopolitical thinking and the course of technological development.

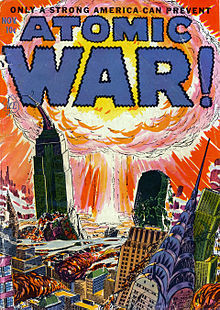

While atomic power was promoted for a time as the epitome of progress and modernity, entering into the nuclear power era also entailed frightful implications of nuclear warfare, the Cold War, mutual assured destruction, nuclear proliferation, the risk of nuclear disaster (potentially as extreme as anthropogenic global nuclear winter), as well as beneficial civilian applications in nuclear medicine. It is no easy matter to fully segregate peaceful uses of nuclear technology from military or terrorist uses (such as the fabrication of dirty bombs from radioactive waste), which complicated the development of a global nuclear-power export industry right from the outset.

In 1973, concerning a flourishing nuclear power industry, the United States Atomic Energy Commission predicted that, by the turn of the 21st century, one thousand reactors would be producing electricity for homes and businesses across the U.S. However, the "nuclear dream" fell far short of what was promised because nuclear technology produced a range of social problems, from the nuclear arms race to nuclear meltdowns, and the unresolved difficulties of bomb plant cleanup and civilian plant waste disposal and decommissioning. Since 1973, reactor orders declined sharply as electricity demand fell and construction costs rose. Many orders and partially completed plants were cancelled.

By the late 1970s, nuclear power had suffered a remarkable international destabilization, as it was faced with economic difficulties and widespread public opposition, coming to a head with the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, both of which adversely affected the nuclear power industry for many decades.

Early years

In 1901, Frederick Soddy and Ernest Rutherford discovered that radioactivity was part of the process by which atoms changed from one kind to another, involving the release of energy. Soddy wrote in popular magazines that radioactivity was a potentially "inexhaustible" source of energy, and offered a vision of an atomic future where it would be possible to "transform a desert continent, thaw the frozen poles, and make the whole earth one smiling Garden of Eden." The promise of an "atomic age," with nuclear energy as the global, utopian technology for the satisfaction of human needs, has been a recurring theme ever since. But "Soddy also saw that atomic energy could possibly be used to create terrible new weapons".

The concept of a nuclear chain reaction was hypothesized in 1933, shortly after Chadwick's discovery of the neutron. Only a few years later, in December 1938 nuclear fission was discovered by Otto Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann. Hahn understood that a "burst" of the atomic nuclei had occurred. Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch gave a full theoretical interpretation and named the process "nuclear fission". The first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction (Chicago Pile-1, or CP-1) took place in December 1942 under the leadership of Enrico Fermi.

In 1945, the pocketbook The Atomic Age heralded the untapped atomic power in everyday objects and depicted a future where fossil fuels would go unused. One science writer, David Dietz, wrote that instead of filling the gas tank of your car two or three times a week, you will travel for a year on a pellet of atomic energy the size of a vitamin pill. Glenn T. Seaborg, who chaired the Atomic Energy Commission, wrote "there will be nuclear powered earth-to-moon shuttles, nuclear powered artificial hearts, plutonium heated swimming pools for SCUBA divers, and much more".

World War II

The phrase Atomic Age was coined by William L. Laurence, a journalist with The New York Times, who became the official journalist for the Manhattan Project which developed the first nuclear weapons. He witnessed both the Trinity test and the bombing of Nagasaki and went on to write a series of articles extolling the virtues of the new weapon. His reporting before and after the bombings helped to spur public awareness of the potential of nuclear technology and in part motivated development of the technology in the U.S. and in the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union would go on to test its first nuclear weapon in 1949.

In 1949, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission chairman, David Lilienthal stated that "atomic energy is not simply a search for new energy, but more significantly a beginning of human history in which faith in knowledge can vitalize man's whole life".

1950s

The phrase gained popularity as a feeling of nuclear optimism emerged in the 1950s in which it was believed that all power generators in the future would be atomic in nature. The atomic bomb would render all conventional explosives obsolete and nuclear power plants would do the same for power sources such as coal and oil. There was a general feeling that everything would use a nuclear power source of some sort, in a positive and productive way, from irradiating food to preserve it, to the development of nuclear medicine. There would be an age of peace and plenty in which atomic energy would "provide the power needed to desalinate water for the thirsty, irrigate the deserts for the hungry, and fuel interstellar travel deep into outer space". This use would render the Atomic Age as significant a step in technological progress as the first smelting of bronze, of iron, or the commencement of the Industrial Revolution.

This included even cars, leading Ford to display the Ford Nucleon concept car to the public in 1958. There was also the promise of golf balls which could always be found and nuclear-powered aircraft, which the U.S. federal government even spent US$1.5 billion researching. Nuclear policymaking became almost a collective technocratic fantasy, or at least was driven by fantasy:

The very idea of splitting the atom had an almost magical grip on the imaginations of inventors and policymakers. As soon as someone said—in an even mildly credible way—that these things could be done, then people quickly convinced themselves ... that they would be done.

In the US, military planners "believed that demonstrating the civilian applications of the atom would also affirm the American system of private enterprise, showcase the expertise of scientists, increase personal living standards, and defend the democratic lifestyle against communism".

Some media reports predicted that thanks to the giant nuclear power stations of the near future electricity would soon become much cheaper and that electricity meters would be removed, because power would be "too cheap to meter."

When the Shippingport reactor went online in 1957 it produced electricity at a cost roughly ten times that of coal-fired generation. Scientists at the AEC's own Brookhaven Laboratory "wrote a 1958 report describing accident scenarios in which 3,000 people would die immediately, with another 40,000 injured".

However Shippingport was an experimental reactor using highly enriched uranium (unlike most power reactors) and originally intended for a (cancelled) nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Kenneth Nichols, a consultant for the Connecticut Yankee and Yankee Rowe nuclear power stations, wrote that while considered "experimental" and not expected to be competitive with coal and oil, they "became competitive because of inflation ... and the large increase in price of coal and oil." He wrote that for nuclear power stations the capital cost is the major cost factor over the life of the plant, hence "antinukes" try to increase costs and building time with changing regulations and lengthy hearings, so that "it takes almost twice as long to build a (U.S.-designed boiling-water or pressurised water) atomic power plant in the United States as in France, Japan, Taiwan or South Korea." French pressurised-water nuclear plants produce 60% of their electric power, and have proven to be much cheaper than oil or coal.

Fear of possible atomic attack from the Soviet Union caused U.S. school children to participate in "duck and cover" civil defense drills.

Atomic City

During the 1950s, Las Vegas, Nevada, earned the nickname "Atomic City" for becoming a hotspot where tourists would gather to watch above-ground nuclear weapons tests taking place at Nevada Test Site. Following the detonation of Able, one of the first atomic bombs dropped at the Nevada Test Site, the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce began advertising the tests as an entertainment spectacle to tourists.

The detonations proved popular and casinos throughout the city capitalised on the tests by advertising hotel rooms or rooftops which offered views of the testing site or by planning "Dawn Bomb Parties" where people would come together to celebrate the detonations. Most parties started at midnight and musicians would perform at the venues until 4:00 a.m. when the party would briefly stop so guests could silently watch the detonation. Some casinos capitalised on the tests further by creating so called "atomic cocktails", a mixture of vodka, cognac, sherry and champagne.

Meanwhile, groups of tourists would drive out into the desert with family or friends to watch the detonations.

Despite the health risks associated with nuclear fallout, tourists and viewers were told to simply "shower". Later on, however, anyone who had worked at the testing site or lived in areas exposed to nuclear fallout fell ill and had higher chances of developing cancer or suffering pre-mature deaths.

1960s

By exploiting the peaceful uses of the "friendly atom" in medical applications, earth removal and, subsequently, in nuclear power plants, the nuclear industry and government sought to allay public fears about nuclear technology and promote the acceptance of nuclear weapons. At the peak of the Atomic Age, the United States government initiated Operation Plowshare, involving "peaceful nuclear explosions". The United States Atomic Energy Commission chairman announced that the Plowshares project was intended to "highlight the peaceful applications of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favorable to weapons development and tests".

Project Plowshare "was named directly from the Bible itself, specifically Micah 4:3, which states that God will beat swords into ploughshares, and spears into pruning hooks, so that no country could lift up weapons against another". Proposed uses included widening the Panama Canal, constructing a new sea-level waterway through Nicaragua nicknamed the Pan-Atomic Canal, cutting paths through mountainous areas for highways, and connecting inland river systems. Other proposals involved blasting caverns for water, natural gas, and petroleum storage. It was proposed to plant underground atomic bombs to extract shale oil in eastern Utah and western Colorado. Serious consideration was also given to using these explosives for various mining operations. One proposal suggested using nuclear blasts to connect underground aquifers in Arizona. Another plan involved surface blasting on the western slope of California's Sacramento Valley for a water transport project. However, there were many negative impacts from Project Plowshare's 27 nuclear explosions. Consequences included blighted land, relocated communities, tritium-contaminated water, radioactivity, and fallout from debris being hurled high into the atmosphere. These were ignored and downplayed until the program was terminated in 1977, due in large part to public opposition, after $770 million had been spent on the project.

In the Thunderbirds TV series, a set of vehicles was presented that were imagined to be completely nuclear, as shown in cutaways presented in their comic-books.

The term "atomic age" was initially used in a positive, futuristic sense, but by the 1960s the threats posed by nuclear weapons had begun to edge out nuclear power as the dominant motif of the atom.

1970s to 1990s

French advocates of nuclear power developed an aesthetic vision of nuclear technology as art to bolster support for the technology. Leclerq compares the nuclear cooling tower to some of the grandest architectural monuments of Western culture:

The age in which we live has, for the public, been marked by the nuclear engineer and the gigantic edifices he has created. For builders and visitors alike, nuclear power plants will be considered the cathedrals of the 20th century. Their syncretism mingles the conscious and the unconscious, religious fulfilment and industrial achievement, the limitations of uses of materials and boundless artistic inspiration, utopia come true and the continued search for harmony.

In 1973, the United States Atomic Energy Commission predicted that, by the turn of the 21st century, one thousand reactors would be producing electricity for homes and businesses across the USA. But after 1973, reactor orders declined sharply as electricity demand fell and construction costs rose. Many orders and partially completed plants were cancelled.

Nuclear power has proved controversial since the 1970s. Highly radioactive materials may overheat and escape from the reactor building. Nuclear waste (spent nuclear fuel) needs to be regularly removed from the reactors and disposed of safely for up to a million years, so that it does not pollute the environment. Recycling of nuclear waste has been discussed, but it creates plutonium which can be used in weapons, and in any case still leaves much unwanted waste to be stored and disposed of. Large, purpose-built facilities for long-term disposal of nuclear waste have been difficult to site, and have not yet reached fruition.

By the late 1970s, nuclear power suffered a remarkable international destabilization, as it was faced with economic difficulties and widespread public opposition, coming to a head with the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, both of which adversely affected the nuclear power industry for decades thereafter. A cover story in the 11 February 1985, issue of Forbes magazine commented on the overall management of the nuclear power program in the United States:

The failure of the U.S. nuclear power program ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history, a disaster on a monumental scale ... only the blind, or the biased, can now think that the money has been well spent. It is a defeat for the U.S. consumer and for the competitiveness of U.S. industry, for the utilities that undertook the program and for the private enterprise system that made it possible.

So, in a period just over 30 years, the early dramatic rise of nuclear power went into equally meteoric reverse. With no other energy technology has there been a conjunction of such rapid and revolutionary international emergence, followed so quickly by equally transformative demise.

21st century

In the 21st century, the label of the "Atomic Age" connotes either a sense of nostalgia or naïveté, and is considered by many to have ended with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, though the term continues to be used by many historians to describe the era following the conclusion of the Second World War. Atomic energy and weapons continue to have a strong effect on world politics in the 21st century. The term is used by some science fiction fans to describe not only the era following the conclusion of the Second World War but also contemporary history up to the present day.

The nuclear power industry has improved the safety and performance of reactors, and has proposed new safer (but generally untested) reactor designs but there is no guarantee that the reactors will be designed, built and operated correctly. Mistakes do occur and the designers of reactors at Fukushima in Japan did not anticipate that a tsunami generated by an earthquake would disable the backup systems that were supposed to stabilize the reactor after the earthquake. According to UBS AG, the Fukushima I nuclear accidents have cast doubt on whether even an advanced economy like Japan can master nuclear safety. Catastrophic scenarios involving terrorist attacks are also conceivable. An interdisciplinary team from MIT has estimated that if nuclear power use tripled from 2005 to 2055 (2%–7%), at least four serious nuclear accidents would be expected in that period.

In September 2012, in reaction to the Fukushima disaster, Japan announced that it would completely phase out nuclear power by 2030, although the likelihood of this goal became unlikely during the subsequent Abe administration. Germany planned to completely phase out nuclear energy by 2022 but was still using 11.9% in 2021. In 2022, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United Kingdom pledged to build up to 8 new reactors to reduce their reliance on gas and oil and hopes that 25% of all energy produced will be by nuclear means.

Chronology

A large anti-nuclear demonstration was held on 6 May 1979, in Washington D.C., when 125,000 people including the Governor of California, attended a march and rally against nuclear power. In New York City on 23 September 1979, almost 200,000 people attended a protest against nuclear power. Anti-nuclear power protests preceded the shutdown of the Shoreham, Yankee Rowe, Millstone I, Rancho Seco, Maine Yankee, and about a dozen other nuclear power plants.

On 12 June 1982, one million people demonstrated in New York City's Central Park against nuclear weapons and for an end to the cold war arms race. It was the largest anti-nuclear protest and the largest political demonstration in American history. International Day of Nuclear Disarmament protests were held on 20 June 1983, at 50 sites across the United States. In 1986, hundreds of people walked from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament. There were many Nevada Desert Experience protests and peace camps at the Nevada Test Site during the 1980s and 1990s.

On 1 May 2005, forty thousand anti-nuclear/anti-war protesters marched past the United Nations in New York, 60 years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was the largest anti-nuclear rally in the U.S. for several decades.

Discovery and development

- 1896 – Henri Becquerel notices that uranium gives off an unknown radiation which fogs photographic film.

- 1898 – Marie Curie discovers thorium gives off a similar radiation. She calls it radioactivity.

- 1903 – Ernest Rutherford begins to speak of the possibility of atomic energy.

- 1905 – Albert Einstein formulates the special theory of relativity which explains the phenomenon of radioactivity as mass–energy equivalence.

- 1911 – Ernest Rutherford formulates a theory about the structure of the atomic nucleus based on his experiments with alpha particles.

- 1930 – Otto Hahn writes an article with his prophecy "The Atom – the source of power of the future?" in the newspaper Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung.

- 1932 – James Chadwick discovers the neutron.

- 1934 – Enrico Fermi begins bombarding uranium with slow neutrons; Ida Noddack predicts that uranium nuclei will break up under bombardment by fast neutrons. (Fermi does not pursue this because his theoretical mathematical predictions do not predict this result.)

- 17 December 1938 – Otto Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann, by bombarding uranium with fast neutrons, discover experimentally and prove nuclear fission with radiochemical methods.

- 6 January 1939 – Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann publish the first paper about their discovery in the German review Die Naturwissenschaften.

- 10 February 1939 – Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann publish the second paper about their discovery in Die Naturwissenschaften, using for the first time the term uranium fission, and predict the liberation of additional neutrons in the fission process.

- 11 February 1939 – Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch publish the first theoretical interpretation of nuclear fission, a term coined by Frisch, in the British review Nature.

- 11 October 1939 – The Einstein–Szilárd letter, suggesting that the United States construct a nuclear weapon, is delivered to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt signs the order to build a nuclear weapon on 6 December 1941.

- 26 February 1941 – Discovery of plutonium by Glenn Seaborg and Arthur Wahl.

- September 1942 – General Leslie Groves takes charge of the Manhattan Project.

- 2 December 1942 – Under the leadership of Fermi, the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction takes place in Chicago, United States, at the Chicago Pile-1.

Nuclear arms deployment

- 16 July 1945 – The first nuclear weapon is detonated in a plutonium form near Socorro, New Mexico, United States in the successful Trinity test.

- 6 August 1945 – The second nuclear weapon, and the first to be deployed in combat, is detonated when the Little Boy uranium bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

- 9 August 1945 – The third nuclear weapon, and the second (and last so far) to be deployed in combat, is detonated when the Fat Man plutonium bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki.

- 5 September 1951 – The U.S. Air Force announces the awarding of a contract for the development of an "atomic-powered airplane".

- 1 November 1952 – The first hydrogen bomb, largely designed by Edward Teller, is tested at Eniwetok Atoll.

"Atoms for Peace"

- 8 December 1953 – U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a speech before the UN General Assembly, announces the Atoms for Peace program to provide nuclear power to developing countries.

- 21 January 1954 – The first nuclear submarine, the USS Nautilus (SSN-571), is launched into the Thames River near New London, Connecticut, United States.

- 27 June 1954 – The first nuclear power plant begins operation near Obninsk, USSR.

- 17 September 1954 – Lewis L. Strauss, chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, states that nuclear energy will be "too cheap to meter".

- 17 October 1956 – The world's first nuclear power station to deliver electricity in commercial quantities opens at Calder Hall in the UK.

- 29 September 1957 – 200+ people die as a result of the Mayak nuclear waste storage tank explosion in Chelyabinsk, Soviet Union. 270,000 people were exposed to dangerous radiation levels.

- 1957 to 1959 – The Soviet Union and the United States both begin deployment of ICBMs.

- 1958 – The neutron bomb, a special type of tactical nuclear weapon developed specifically to release a relatively large portion of its energy as energetic neutron radiation, is invented by Samuel Cohen of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- 1960 – Herman Kahn publishes the book On Thermonuclear War.

- November 1961 – In Fortune magazine, an article by Gilbert Burck appears outlining the plans of Nelson Rockefeller, Edward Teller, Herman Kahn, and Chet Holifield for the construction of an enormous network of concrete-lined underground fallout shelters throughout the United States sufficient to shelter millions of people to serve as a refuge in case of nuclear war.

- 12 October 1962 to 28 October 1962 – The Cuban Missile Crisis brings Earth to the brink of nuclear war.

- 10 October 1963 – The Partial Test Ban Treaty goes into effect, banning above ground nuclear testing.

- 26 August 1966 – The first pebble bed reactor goes online in Jülich, West Germany (some nuclear engineers think that the pebble bed reactor design can be adapted for atomic powered vehicles).

- 27 January 1967 – The Outer Space Treaty bans the deployment of nuclear weapons in space.

- 1968 – Physicist Freeman Dyson proposes building a space ark using an Orion nuclear-pulse propulsion rocket powered by hydrogen bombs. The rocket would have a payload of 50,000 tonnes, a crew of 240, and be able to travel at 3.3% of the speed of light and would reach Alpha Centauri in 133 years. It would cost $367 billion in 1968 dollars, which is the equivalent of about $2.2 trillion in 2012 dollars.

Three Mile Island and Chernobyl

- 28 March 1979 – The Three Mile Island accident occurs at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, dampening enthusiasm in the United States for nuclear power, and causing a dramatic shift in the growth of nuclear power in the United States.

- 6 May 1979 – A large anti-nuclear demonstration was held in Washington, D.C., when 125,000 people including the Governor of California, attended a march and rally against nuclear power.[42]

- 23 September 1979 – In New York City, almost 200,000 people attended a protest against nuclear power.

- 26 April 1986 – The Chernobyl disaster occurs at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near Pripyat, Ukraine, USSR, reducing enthusiasm for nuclear power among many people in the world, and causing a dramatic shift in the growth of nuclear power.

Nuclear arms reduction

- 8 December 1987 – The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty is signed in Washington 1987. Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev agreed after negotiations following the 11–12 October 1986 Reykjavík Summit to go farther than a nuclear freeze – they agreed to reduce nuclear arsenals. IRBMs and SRBMs were eliminated.

- 1993–2007 – Nuclear power is the primary source of electricity in France. Throughout these two decades, France produced over three quarters of its power from nuclear sources (78.8%), the highest percentage in the world at the time.

- 31 July 1991 – As the Cold War ends, the Start I treaty is signed by the United States and the Soviet Union, reducing the deployed nuclear warheads of each side to no more than 6,000 each.

- 1993 – The Megatons to Megawatts Program is agreed upon by Russia and the United States and begins to be implemented in 1995. When it is completed in 2013, five hundred tonnes of uranium derived from 20,000 nuclear warheads from Russia will have been converted from weapons-grade to reactor-grade uranium and used in United States nuclear plants to generate electricity. This has provided 10% of the electrical power of the U.S. (50% of its nuclear power) during the 1995–2013 period.

- 2006 – Patrick Moore, an early member of Greenpeace and environmentalists such as Stewart Brand suggest the deployment of more advanced nuclear power technology for electric power generation (such as pebble-bed reactors) to combat global warming.

- 21 November 2006 – Implementation of the ITER fusion power reactor project near Cadarache, France is begun. Construction is to be completed in 2016 with the hope that the research conducted there will allow the introduction of practical commercial fusion power plants by 2050.

- 2006–2009 – A number of nuclear engineers begin to suggest that, to combat global warming, it would be more efficient to build nuclear reactors that operate on the thorium cycle.

- 8 April 2010 – The New START treaty is signed by the United States and Russia in Prague. It mandates the eventual reduction by both sides to no more than 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear weapons each.

Fukushima

- 11 March 2011 – A tsunami resulting from the Tōhoku earthquake causes severe damage to the Fukushima I nuclear power plant in Japan, causing partial nuclear meltdowns in several of the reactors. Many international leaders express concerns about the accidents and some countries re-evaluate existing nuclear energy programs. On 11 April 2011 this event was rated level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale by the Japanese government's nuclear safety agency. Other than the Chernobyl disaster, it is the only nuclear accident to be rated at level 7, the highest level on the scale, and caused the most dramatic shift in nuclear policy to date.

Influence on popular culture

- 1945 – The Atomaton chapter of Sweet Adelines was formed by Edna Mae Anderson after she and her sister singers decided, "We have an atom of an idea and a ton of energy." The name also recognized the Atomic Age—just three days after Sweet Adelines was founded (13 July 1945), the first nuclear bomb, Trinity, was detonated.

- 5 July 1946 – The bikini swimsuit, named after Bikini Atoll, where an atomic bomb test called Operation Crossroads had taken place a few days earlier on 1 July 1946, was introduced at a fashion show in Paris.

- 1954 – Them!, a science fiction film about humanity's battle with a nest of giant mutant ants, was one of the first of the "nuclear monster" movies.

- 1954 – The science fiction film Godzilla was released, about an iconic fictional monster that is a gigantic irradiated dinosaur, transformed from the fallout of an H-Bomb test.

- 23 January 1957 – Walt Disney Productions released the film "Our Friend the Atom" describing the marvelous benefits of atomic power. As well as being presented as an episode on the TV show Disneyland, this film was also shown to almost all baby boomers in their public school auditoriums or their science classes and was instrumental in creating within that generation a mostly favorable attitude toward nuclear power.

- 1957 – The current leader of the Nizari sect of Ismaili Shia Islam, Shah Karim al-Husayni, the Aga Khan IV, acceded to the Imamship at age 20. One of the titles bestowed on him by his followers was his designation as The Imam of the Atomic Age.

- 1958 – The Atomium was constructed for the Brussels World's Fair.

- 1958 –The peace symbol was designed for the British nuclear disarmament movement by Gerald Holtom.

- 1959 – The popular film On the Beach shows the last remnants of humanity in Australia awaiting the end of the human race after a nuclear war.

- 1964 – The film Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (aka Dr. Strangelove), a black comedy directed by Stanley Kubrick about an accidentally triggered nuclear war, was released.

- 1970 – The underground comic book Hydrogen Bomb Funnies is published.

- 1982 – The documentary film The Atomic Cafe, detailing society's attitudes toward the atomic bomb in the early Atomic Age, debuted to widespread acclaim.

- 1982 – Jonathan Schell's book Fate of the Earth, about the consequences of nuclear war, is published. The book "forces even the most reluctant person to confront the unthinkable: the destruction of humanity and possibly most life on Earth". The best-selling book instigated the Nuclear Freeze campaign.

- 1983 – The cartoon book The End by cartoonist Skip Morrow, about the lighter side of nuclear apocalypse, is published.

- 20 November 1983 – The Day After, an American television movie was aired on the ABC Television Network, and also in the Soviet Union. The film portrays a fictional nuclear war between the United States/NATO and the Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact. After the film, a panel discussion is presented in which Carl Sagan suggested that we need to reduce the number of nuclear weapons as a matter of "planetary hygiene". This film was seen by over 100,000,000 people and was instrumental in greatly increasing public support for the Nuclear Freeze campaign.

- Beginning in the 1990s, nostalgia stores that specialize in selling modern furniture or artifacts from the 1950s often have included the words Atomic Age as part of the name of, or advertising for the store.

- 1999 – Blast from the Past was released. It is a romantic comedy film about a nuclear physicist, his wife, and son that enter a well-equipped spacious fallout shelter during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. They do not emerge until 35 years later, in 1997. The film shows their reaction to contemporary society.

- 1999 – Larry Niven published the science fiction novel Rainbow Mars. In this novel, in the 31st century, Earth uses a dating system based on what is called the Atomic Era, in which the year one is 1945. Thus, what we call the year 3053 A.D. (the year the novel begins) is in the novel the year 1108 A.E.

- Autumn 2007 – Bachelor Pad Magazine, "The New Digest of Atomic Age Culture" began publication.

- 23 November 2010 – Civilization V, the fifth game in a long-running popular turn-based strategy game series, was released. One of the many eras in the game is the Atomic era where players can make ICBMs, nuclear reactors and submarines and even sci-fi style giant nuclear-powered robots.

- 25 May 2018 – Parmanu, an Indian movie regarding the Second Pokhran Project was released.