| Animal testing |

|---|

|

| Main articles |

| Testing on |

| Issues |

| Cases |

| Companies |

| Groups/campaigns |

|

| Writers/activists |

| Categories |

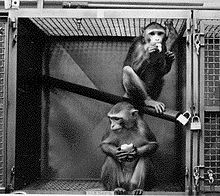

Experiments involving non-human primates (NHPs) include toxicity testing for medical and non-medical substances; studies of infectious disease, such as HIV and hepatitis; neurological studies; behavior and cognition; reproduction; genetics; and xenotransplantation. Around 65,000 NHPs are used every year in the United States, and around 7,000 across the European Union. Most are purpose-bred, while some are caught in the wild.

Their use is controversial. According to the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, NHPs are used because their brains share structural and functional features with human brains, but "while this similarity has scientific advantages, it poses some difficult ethical problems, because of an increased likelihood that primates experience pain and suffering in ways that are similar to humans." Some of the most publicized attacks on animal research facilities by animal rights groups have occurred because of primate research. Some primate researchers have abandoned their studies because of threats or attacks.

In December 2006, an inquiry chaired by Sir David Weatherall, emeritus professor of medicine at Oxford University, concluded that there is a "strong scientific and moral case" for using primates in some research. The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection argues that the Weatherall report failed to address "the welfare needs and moral case for subjecting these sensitive, intelligent creatures to a lifetime of suffering in UK labs".

Legal status

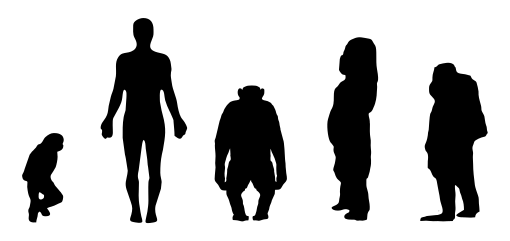

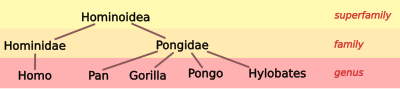

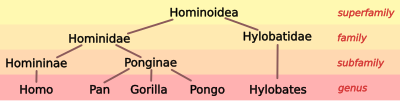

Human beings are recognized as persons and protected in law by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and by all governments to varying degrees. Non-human primates are not classified as persons in most jurisdictions, which largely means their individual interests have no formal recognition or protection. The status of non-human primates has generated much debate, particularly through the Great Ape Project (GAP), which argues that great apes (gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos) should be given limited legal status and the protection of three basic interests: the right to live, the protection of individual liberty, and the prohibition of torture.

In 1997, the United Kingdom announced a policy of no longer granting licenses for research involving great apes, the first ever measure to ban primate use in research. Announcing the UK’s ban, the British Home Secretary said: "[T]his is a matter of morality. The cognitive and behavioural characteristics and qualities of these animals mean it is unethical to treat them as expendable for research." Britain continues to use other primates in laboratories, such as macaques and marmosets. In 2006 the permanency of the UK ban was questioned by Colin Blakemore, head of the Medical Research Council. Blakemore, while stressing he saw no "immediate need" to lift the ban, argued "that under certain circumstances, such as the emergence of a lethal pandemic virus that only affected the great apes, including man, then experiments on chimps, orang-utans and even gorillas may become necessary." The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection described Blakemore's stance as "backward-looking." In 1999, New Zealand was the first country to ban experimentation on great apes by law.

On June 25, 2008, Spain became the first country to announce that it will extend rights to the great apes in accordance with GAP's proposals. An all-party parliamentary group advised the government to write legislation giving chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans the right to life, to liberty, and the right not to be used in experiments. The New York Times reported that the legislation will make it illegal to kill apes, except in self-defense. Torture, which will include medical experiments, will be not allowed, as will arbitrary imprisonment, such as for circuses or films.

An increasing number of other governments are enacting bans. As of 2006, Austria, New Zealand (restrictions on great apes only and not a complete ban), the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom had introduced either de jure or de facto bans. The ban in Sweden does not extend to non-invasive behavioral studies, and graduate work on great ape cognition in Sweden continues to be carried out on zoo gorillas, and supplemented by studies of chimpanzees held in the U.S. Sweden's legislation also bans invasive experiments on gibbons.

In December 2005, Austria outlawed experiments on any apes, unless it is conducted in the interests of the individual animal. In 2002, Belgium announced that it was working toward a ban on all primate use, and in the UK, 103 MPs signed an Early Day Motion calling for an end to primate experiments, arguing that they cause suffering and are unreliable. No licenses for research on great apes have been issued in the UK since 1998. The Boyd Group, a British group comprising animal researchers, philosophers, primatologists, and animal advocates, has recommended a global prohibition on the use of great apes.

The use of non-human primates in the EU is regulated under the Directive 2010/63/EU. The directive took effect on January 1, 2013. The directive permits the use of non-human primates if no other alternative methods are available. Testing on non-human primates is permitted for basic and applied research, quality and safety testing of drugs, food and other products and research aimed on the preservation of the species. The use of great apes is generally not permitted, unless it is believed that the actions are essential to preserve the species or in relation to an unexpected outbreak of a life-threatening or debilitating clinical condition in human beings. The directive stresses the use of the 3R principle (replacement, refinement, reduction) and animal welfare when conducting animal testing on non-human primates.

A 2013 amendment to the German Animal Welfare Act, with special regulations for monkeys, resulted in a near total ban on the use of great apes as laboratory animals. The last time great apes were used in laboratory experiments in Germany was 1991.

Species and numbers used

Most of the NHPs used are one of three species of macaques, accounting for 79% of all primates used in research in the UK, and 63% of all federally funded research grants for projects using primates in the U.S. Lesser numbers of marmosets, tamarins, spider monkeys, owl monkeys, vervet monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and baboons are used in the UK and the U.S. Great apes have not been used in the UK since a government policy ban in 1998. In the U.S., research laboratories employ the use of 1,133 chimpanzees as of October 2006.

| Country | Total | Reporting Year | Procedures/Animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 0 | 2017 | Procedures |

| Belgium | 40 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Bulgaria | 0 | 2017 | Procedures |

| Canada | 7556 | 2016 | Animals |

| Croatia | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Cyprus | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Czech Republic | 36 | 2017 | Animals |

| Denmark | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Estonia | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Finland | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| France | 3508 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Germany | 2418 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Greece | 3 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Hungary | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Ireland | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Israel | 35 | 2017 | Animals |

| Italy | 511 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Latvia | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Lithuania | 0 | 2015 | Procedures |

| Luxembourg | 0 | 2017 | Animals |

| Malta | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Netherlands | 120 | 2016 | Procedures |

| New Zealand | 0 | 2015 | Animals |

| Poland | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Portugal | 0 | 2014 | Procedures |

| Romania | 0 | 2015 | Procedures |

| Slovakia | 0 | 2017 | Procedures |

| Slovenia | 0 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Spain | 228 | 2016 | Procedures |

| South Korea | 2403 | 2017 | Animals |

| Sweden | 38 | 2016 | Procedures |

| Switzerland | 181 | 2017 | Animals |

| United Kingdom | 2960 | 2017 | Procedures |

| United States | 71188 | 2016 | Animals |

Most primates are purpose-bred, while some are caught in the wild. In 2011 in the EU, 0.05% of animals used in animal testing procedures were non-human primates.

In 1996, the British Animal Procedures Committee recommended new measures for dealing with NHPs. The use of wild-caught primates was banned, except where "exceptional and specific justification can be established"; specific justification must be made for the use of Old World primates (but not for the use of New World primates); approval for the acquisition of primates from overseas is conditional upon their breeding or supply center being acceptable to the Home Office; and each batch of primates acquired from overseas must be separately authorized.

Prevalence

There are indications that NHP use is on the rise in some countries, in part because biomedical research funds in the U.S. have more than doubled since the 1990s. In 2000, the NIH published a report recommending that the Regional Primate Research Center System be renamed the National Primate Research Center System and calling for an increase in the number of NHPs available to researchers, and stated that "nonhuman primates are crucial for certain types of biomedical and behavioral research." This assertion has been challenged. In the U.S., the Oregon and California National Primate Research Centers and New Iberia Research Center have expanded their facilities.

In 2000 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) invited applications for the establishment of new breeding specific pathogen free colonies; and a new breeding colony projected to house 3,000 NHPs has been set up in Florida. The NIH's National Center for Research Resources claimed a need to increase the number of breeding colonies in its 2004–2008 strategic plan, as well as to set up a database, using information provided through a network of National Primate Research Centers, to allow researchers to locate NHPs with particular characteristics. China is also increasing its NHP use, and is regarded as attractive to Western companies because of the low cost of research, the relatively lax regulations and the increase in animal-rights activism in the West.

In 2013, British Home Office figures show that the number of primates used in the UK was at 2,440, down 32% from 3,604 NHPs in 1993. Over the same time period, the number of procedures involving NHPs fell 29% from 4,994 from to 3,569 procedures.

Sources

The American Society of Primatologists writes that most NHPs in laboratories in the United States are bred domestically. Between 12,000–15,000 are imported each year, specifically rhesus macaque monkeys, cynomolgus (crab-eating) macaque monkeys, squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and baboons. Monkeys are imported from China, Mauritius, the Philippines, and Peru.

China exported over 12,000 macaques for research in 2001 (4,500 to the U.S.), all from self-sustaining purpose-bred colonies. The second largest source is Mauritius, from which 3,440 purpose-bred cynomolgus macaques were exported to the U.S. in 2001.

In Europe, an estimated 70% of research primates are imported, and the rest are purpose-bred in Europe. Around 74% of these imports come from China, with most of the rest coming from Mauritius.

Use

General

NHPs are used in research into HIV, neurology, behavior, cognition, reproduction, Parkinson's disease, stroke, malaria, respiratory viruses, infectious disease, genetics, xenotransplantation, drug abuse, and also in vaccine and drug testing. According to The Humane Society of the United States, chimpanzees are most often used in hepatitis research, and monkeys in SIV research. Animals used in hepatitis and SIV studies are often caged alone.

Eighty-two percent of primate procedures in the UK in 2006 were in applied studies, which the Home Office defines as research conducted for the purpose of developing or testing commercial products. Toxicology testing is the largest use, which includes legislatively required testing of drugs. The second largest category of research using primates is "protection of man, animals, or environment", accounting for 8.9% of all procedures in 2006. The third largest category is "fundamental biological research", accounting for 4.9% of all UK primate procedures in 2006. This includes neuroscientific study of the visual system, cognition, and diseases such as Parkinson's, involving techniques such as inserting electrodes to record from or stimulate the brain, and temporary or permanent inactivation of areas of tissue.

Primates are the species most likely to be re-used in experiments. The Research Defence Society writes that re-use is allowed if the animals have been used in mild procedures with no lasting side-effects. This is contradicted by Dr. Gill Langley of the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, who gives as an example of re-use the licence granted to Cambridge University to conduct brain experiments on marmosets. The protocol sheet stated that the animals would receive "multiple interventions as part of the whole lesion/graft repair procedure." Under the protocol, a marmoset could be given acute brain lesions under general anaesthetic, followed by tissue implantation under a second general anaesthetic, followed again central cannula implantation under a third. The re-use is allowable when required to meet scientific goals, such as this case in which some procedures are required as preparatory for others.

Methods of restraint

One of the disadvantages of using NHPs is that they can be difficult to handle, and various methods of physical restraint have to be used. Viktor Reinhardt of the Wisconsin Regional Primate Research Center writes that scientists may be unaware of the way in which their research animals are handled, and therefore fail to take into account the effect the handling may have had on the animals' health, and thereby on any data collected. Reinhardt writes that primatologists have long recognized that restraint methods may introduce an "uncontrolled methodological variable", by producing resistance and fear in the animal. "Numerous reports have been published demonstrating that non-human primates can readily be trained to cooperate rather than resist during common handling procedures such as capture, venipuncture, injection and veterinary examination. Cooperative animals fail to show behavioural and physiological signs of distress."

Reinhardt lists common restraint methods as: squeeze-back cages, manual restraint, restraint boards, restraint chairs, restraint chutes, tethering, and nets. Alternatives include:

- chemical restraint; for example, ketamine, a sedative, may be given to the animal before a restraint procedure, reducing stress-hormone production;

- psychological support, in which an animal under restraint has visual and auditory contact with the animal's cage-mate. Blood pressure and heart rate responses to restraint have been measurably reduced using psychological support.

- training animals to cooperate with restraint. Such methods have been used and resulted in unmeasurable stress hormone responses to venipuncture, and no notable distress to being captured in a transport box.

Chimpanzees in the United States

As of 2013, the U.S. and Gabon were the only countries that still allowed chimpanzees to be used for medical experiments. The U.S. is the world's largest user of chimpanzees for biomedical research, with approximately 1,200 individual subjects in U.S. labs as of middle 2011, dropping to less than 700 as of 2016. Japan also still keeps a dozen chimpanzees in a research project for chimpanzee cognition (see Ai (chimpanzee)).

Chimpanzees routinely live 30 years in captivity, and can reach 60 years of age.

Most of the labs either conduct or make the chimpanzees available for invasive research, defined as "inoculation with an infectious agent, surgery or biopsy conducted for the sake of research and not for the sake of the chimpanzee, and/or drug testing." Two federally funded laboratories have used chimps: Yerkes National Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Southwest National Primate Research Center in San Antonio, Texas. By 2008, five hundred chimps had been retired from laboratory use in the U.S. and live in sanctuaries in the U.S. or Canada.

Their importation from the wild was banned in 1973. From then until 1996, chimpanzees in U.S. facilities were bred domestically. Some others were transferred from the entertainment industry to animal testing facilities as recently as 1983, although it is not known if any animals that were transferred from the entertainment industry are still in testing centers. Animal sanctuaries were not an option until the first North American sanctuary that would accept chimpanzees opened in 1976.

In 1986, to prepare for research on AIDS, the U.S. bred them aggressively, with 315 breeding chimpanzees used to produce 400 offspring. By 1996, it was clear that SIV/HIV-2/SHIV in macaque monkeys was a preferred scientific AIDS model to the chimpanzees, which meant there was a surplus. A five-year moratorium on breeding was therefore imposed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) that year, and it has been extended annually since 2001. As of October 2006, the chimpanzee population in US laboratories had declined to 1133 from a peak of 1500 in 1996.

Chimpanzees tend to be used repeatedly over decades, rather than used and killed as with most laboratory animals. Some individual chimpanzees currently in U.S. laboratories have been used in experiments for over 40 years. The oldest known chimpanzee in a U.S. lab is Wenka, who was born in a laboratory in Florida on May 21, 1954. She was removed from her mother on the day of birth to be used in a vision experiment that lasted 17 months, then sold as a pet to a family in North Carolina. She was returned to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in 1957 when she became too big to handle. Since then, she has given birth six times, and has been used in research into alcohol use, oral contraceptives, aging, and cognitive studies.

With the publication of the chimpanzee genome, there are reportedly plans to increase the use of chimpanzees in labs, with scientists arguing that the federal moratorium on breeding chimpanzees for research should be lifted. Other researchers argue that chimpanzees are unique animals and should either not be used in research, or should be treated differently. Pascal Gagneux, an evolutionary biologist and primate expert at the University of California, San Diego, argues that, given chimpanzees' sense of self, tool use, and genetic similarity to human beings, studies using chimpanzees should follow the ethical guidelines that are used for human subjects unable to give consent. Stuart Zola, director of the Yerkes National Primate Research Laboratory, disagrees. He told National Geographic: "I don't think we should make a distinction between our obligation to treat humanely any species, whether it's a rat or a monkey or a chimpanzee. No matter how much we may wish it, chimps are not human."

In January 2011 the Institute of Medicine was asked by the NIH to examine whether the government should keep supporting biomedical research on chimpanzees. The NIH called for the study after protests by the Humane Society of the United States, primatologist Jane Goodall and others, when it announced plans to move 186 semi-retired chimpanzees back into active research. On December 15, 2011, the Institute of Medicine committee concluded in their "Chimpanzees in Biomedical and Behavioral Research: Assessing the Necessity" report that, "while the chimpanzee has been a valuable animal model in past research, most current use of chimpanzees for biomedical research is unnecessary," as scientific research indicated a decreasing need for the use of chimpanzees due to the emergence of non-chimpanzee models. Later that day Francis Collins, a head of the NIH, said the agency would stop issuing new awards for research involving chimpanzees until the recommendations developed by the IOM are implemented.

On 21 September 2012, the NIH announced that 110 chimpanzees owned by the government were to be retired. The NIH owned about 500 chimpanzees for research, and this move signified the first step to wind down its investment in chimpanzee research, according to Collins. Housed at the New Iberia Research Center in Louisiana, 10 of the retired chimpanzees were to go to the chimpanzee sanctuary Chimp Haven while the rest were to go to Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio. However, concerns over the chimpanzees' status in the Texas Biomedical Research Institute as ‘research ineligible’ rather than ‘retired’ prompted the NIH to reconsider the plan. On 17 October 2012, it was announced that as many chimpanzees as possible will be relocated to Chimp Haven by August 2013, and that eventually all 110 will move there.

In 2013 the NIH agreed with the IOM's recommendations that experimentation on chimpanzees was unnecessary and rarely helped in advancing human health for infectious diseases and that the NIH would phase out most of its government-funded experiments on chimpanzees. On 22 January 2013, an NIH task force released a report calling for the government to retire most of the chimpanzees under U.S. government support. The panel concluded that the animals provide little benefit in biomedical discoveries except in a few disease cases which can be supported by a small population of 50 primates for future research. It suggested that other approaches, such as genetically altered mice, should be developed and refined instead. On 13 November 2013, Congress and the Senate passed ‘The Chimpanzee Health Improvement, Maintenance and Protection Act’, which approved funding to expand the capacity of Chimp Haven and other chimpanzee sanctuaries, allowing for the transfer of almost all of the apes owned by the federal government to live in a more natural and group environment. The transfer was expected to take up to five years, at which point all but 50 chimpanzees were to have been successfully ‘retired’.

On 11 June 2013, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) proposed to list captive chimpanzees as endangered, matching its existing classification for wild chimpanzees. Until the USFWS proposal, chimpanzees were the only species with a split listing that did not also classify captive members of the species as endangered. Before the proposal gained final approval, it was unclear what effect it would have on laboratory research.

Two years later, on June 16, 2015, the USFWS announced that it has designated both captive and wild chimpanzees as endangered. In November 2015 the NIH announced it would no longer support biomedical research on chimpanzees and release its remaining 50 chimpanzees to sanctuaries. The agency would also develop a plan for phasing out NIH support for the remaining chimps that are supported by, but not owned by, the NIH.

In January 2014, Merck & Co. announced that the company will not use chimpanzees for research, joining over 20 pharmaceutical companies and contract laboratories that have made the commitment. As the trend continues, it is estimated the remaining non-government owned 1,000 chimpanzees will be retired to sanctuaries around 2020.

Notable studies

Polio

In the 1940s, Jonas Salk used rhesus monkey cross-contamination studies to isolate the three forms of the polio virus that crippled hundreds of thousands of people yearly across the world at the time. Salk's team created a vaccine against the strains of polio in cell cultures of green monkey kidney cells. The vaccine was made publicly available in 1955, and reduced the incidence of polio 15-fold in the USA over the following five years.

Albert Sabin made a superior "live" vaccine by passing the polio virus through animal hosts, including monkeys. The vaccine was produced for mass consumption in 1963 and is still in use today. It had virtually eradicated polio in the United States by 1965.

Split-brain experiments

In the 1950s, Roger Sperry developed split-brain preparations in non-human primates that emphasized the importance of information transfer that occurred in these neocortical connections. For example, learning on simple tasks, if restricted in sensory input and motor output to one hemisphere of a split-brain animal, would not transfer to the other hemisphere. The right brain has no idea what the left brain is up to, if these specific connections are cut. Those experiments were followed by tests on human beings with epilepsy who had undergone split-brain surgery, which established that the neocortical connections between hemispheres are the principal route for cognition to transfer from one side of the brain to another. These experiments also formed the modern basis for lateralization of function in the human brain.

Vision experiments

In the 1960s, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel demonstrated the macrocolumnar organization of visual areas in cats and monkeys, and provided physiological evidence for the critical period for the development of disparity sensitivity in vision (i.e., the main cue for depth perception). They were awarded a Nobel Prize for their work.

Deep-brain stimulation

In 1983, designer drug users took MPTP, which created a Parkinsonian syndrome. Later that same year, researchers reproduced the effect in non-human primates. Over the next seven years, the brain areas that were over- and under-active in Parkinson's were mapped out in normal and MPTP-treated macaque monkeys using metabolic labelling and microelectrode studies. In 1990, deep brain lesions were shown to treat Parkinsonian symptoms in macaque monkeys treated with MPTP, and these were followed by pallidotomy operations in humans with similar efficacy. By 1993, it was shown that deep brain stimulation could effect the same treatment without causing a permanent lesion of the same magnitude. Deep brain stimulation has largely replaced pallidotomy for treatment of Parkinson's patients that require neurosurgical intervention. Current estimates are that 20,000 Parkinson's patients have received this treatment.

AIDS

The non-human primate models of AIDS, using HIV-2, SHIV, and SIV in macaques, have been used as a complement to ongoing research efforts against the virus. The drug tenofovir has had its efficacy and toxicology evaluated in macaques, and found longterm-highdose treatments had adverse effects not found using short term-high dose treatment followed by long term-low dose treatment. This finding in macaques was translated into human dosing regimens. Prophylactic treatment with anti-virals has been evaluated in macaques, because introduction of the virus can only be controlled in an animal model. The finding that prophylaxis can be effective at blocking infection has altered the treatment for occupational exposures, such as needle exposures. Such exposures are now followed rapidly with anti-HIV drugs, and this practice has resulted in measurable transient virus infection similar to the NHP model. Similarly, the mother-to-fetus transmission, and its fetal prophylaxis with antivirals such as tenofovir and AZT, has been evaluated in controlled testing in macaques not possible in humans, and this knowledge has guided antiviral treatment in pregnant mothers with HIV. "The comparison and correlation of results obtained in monkey and human studies is leading to a growing validation and recognition of the relevance of the animal model. Although each animal model has its limitations, carefully designed drug studies in nonhuman primates can continue to advance our scientific knowledge and guide future clinical trials."

Treatment of anxiety and depression

The reason for studying primates is due to the similar complexity of the cerebral processes in the human brain which controls emotional responses and can be beneficial for testing new pharmacological treatments. An experiment published in the Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews describes habituation of the black-tufted marmoset in a figure eight maze model. They were presented with a taxidermized wild-cat, rattlesnake, a hawk as well as a stuffed toy bear on one side of the maze. Two cameras and a two way mirror was used to observe the difference between the monkeys natural behaviors versus the behaviors expressed by the diazepam induced monkeys in thirteen different locations inside the maze. Scientist Barros and his colleagues created this model to allow the monkeys to roam a less confined environment and slightly eliminate outside factors that may induce stress.

Allegations

Many of the best-known allegations of abuse made by animal protection or animal rights groups against animal-testing facilities involve non-human primates.

University of Wisconsin–Madison

The so-called "pit of despair" was used in experiments conducted on rhesus macaque monkeys during the 1970s by American comparative psychologist Harry Harlow at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The aim of the research was to produce clinical depression. The vertical chamber was a stainless-steel bin with slippery sides that sloped to a rounded bottom. A 3/8 in. wire mesh floor 1 in. above the bottom of the chamber allowed waste material to drop out of holes. The chamber had a food box and a water-bottle holder, and was covered with a pyramid top so that the monkeys were unable to escape. Harlow placed baby monkeys in the chamber alone for up to six weeks. Within a few days, they stopped moving about and remained huddled in a corner. The monkeys generally exhibited marked social impairment and peer hostility when removed from the chamber; most did not recover.

University of California, Riverside

On April 21, 1985, activists of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) broke into the UC Riverside laboratories and removed hundreds of animals. According to Vicky Miller of PETA, who reported the raid to newswire services, UC-Riverside "has been using animals in experiments on sight deprivation and isolation for the last two years and has recently received a grant, paid for with our tax dollars, to continue torturing and killing animals." According to UCR officials, the ALF claims of animal mistreatment were "absolutely false," and the raid would result in long-term damage to some of the research projects, including those aimed at developing devices and treatment for blindness. UCR officials also reported the raid also included smashing equipment and resulted in several hundred thousand dollars of damage.

Covance

In Germany in 2004, journalist Friedrich Mülln took undercover footage of staff in Covance in Münster, Europe's largest primate-testing center. Staff were filmed handling monkeys roughly, screaming at them, and making them dance to blaring music. The monkeys were shown isolated in small wire cages with little or no natural light, no environmental enrichment, and subjected to high noise levels from staff shouting and playing the radio. Primatologist Jane Goodall described their living conditions as "horrendous."

A veterinary toxicologist employed as a study director at Covance in Vienna, Virginia, from 2002 to 2004, told city officials in Chandler, Arizona, that Covance was dissecting monkeys while the animals were still alive and able to feel pain. The employee approached the city with her concerns when she learned that Covance planned to build a new laboratory in Chandler.

She alleged that three monkeys in the Vienna laboratory had pushed themselves up on their elbows and had gasped for breath after their eyes had been removed, and while their intestines were being removed during necropsies (autopsy). When she expressed concern at the next study directors' meeting, she says she was told that it was just a reflex. She told city officials that she believed such movements were not reflexes but suggested "botched euthanasia performed by inadequately trained personnel." She alleged that she was ridiculed and subjected to thinly veiled threats when she contacted her supervisors about the issue.

University of Cambridge

In the UK, after an undercover investigation in 1998, the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV), a lobby group, reported that researchers in Cambridge University's primate-testing labs were sawing the tops off marmosets' heads, inducing strokes, then leaving them overnight without veterinarian care, because staff worked only nine to five. The experiments used marmosets that were first trained to perform certain behavioral and cognitive tasks, then re-tested after brain damage to determine how the damage had affected their skills. The monkeys were deprived of food and water to encourage them to perform the tasks, with water being withheld for 22 out of every 24 hours.

The Research Defence Society defended Cambridge's research. The RDS wrote that the monkeys were fully anaesthetised, and appropriate pain killers were given after the surgery. "On recovery from the anaesthesia, the monkeys were kept in an incubator, offered food and water and monitored at regular intervals until the early evening. They were then allowed to sleep in the incubators until the next morning. No monkeys died unattended during the night after stroke surgery." A court rejected BUAV's application for a judicial review. BUAV appealed.

Columbia University

In 2003, CNN reported that a post-doctoral veterinarian at Columbia University complained to the university's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee about experiments being conducted on baboons by E. Sander Connolly, an assistant professor of neurosurgery. The experiment involved a left transorbital craniectomy to expose the left internal carotid artery to occlude the blood supply to the brain. A clamp was placed on this blood vessel until the stroke was induced, after which Connolly would test a potential neuroprotective drug which if effective, would be used to treat humans suffering from stroke.

Connolly developed this methodology to make more consistent stroke infarcts in primates, which would improve the detection of differences in stroke treatment groups, and "provide important information not obtainable in rodent models." The baboons were kept alive after the surgery for observation for three to ten days in a state of "profound disability" which would have been "terrifying," according to neurologist Robert Hoffman. Connolly's published animal model states that animals were kept alive for three days, and that animals that were successfully self-caring were kept alive for 10 days. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals has expressed strong opposition to this experiment and has written multiple letters to the NIH and other federal agencies to halt further mistreatment of baboons and other animals at Columbia.

An investigation by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found "no indication that the experiments...violated federal guidelines." The Dean of Research at Columbia's School of Medicine said that Connolly had stopped the experiments because of threats from animal rights activists, but still believed his work was humane and potentially valuable.

Attacks on researchers

In 2006, activists forced a primate researcher at UCLA to shut down the experiments in his lab. His name, phone number, and address were posted on the website of the UCLA Primate Freedom Project, along with a description of his research, which stated that he had "received a grant to kill 30 macaque monkeys for vision experiments. Each monkey is first paralyzed, then used for a single session that lasts up to 120 hours, and finally killed." Demonstrations were held outside his home. A Molotov cocktail was placed on the porch of what was believed to be the home of another UCLA primate researcher. Instead, it was accidentally left on the porch of an elderly woman unrelated to the university. The Animal Liberation Front claimed responsibility for the attack.

As a result of the campaign, the researcher sent an email to the Primate Freedom Project stating "you win", and "please don't bother my family anymore." In another incident at UCLA in June 2007, the Animal Liberation Brigade placed a bomb under the car of a UCLA children's ophthalmologist, who performs experiments on cats and rhesus monkeys; the bomb had a faulty fuse and did not detonate. UCLA is now refusing Freedom of Information Act requests for animal medical records.

The house of UCLA researcher Edythe London was intentionally flooded on October 20, 2007, in an attack claimed by the Animal Liberation Front. London conducts research on addiction using non-human primates, and no claims were made by the ALF of any violation of any rules or regulations regarding the use of animals in research. London responded by writing an op-ed column in the LA Times titled "Why I use laboratory animals."

In 2009, a UCLA neurobiologist known for using animals to research drug addiction and other psychiatric disorders had his car burned for the second time.

China

In infectious disease research, China invests more than the U.S. does in conducting research on non-human primates. "Select agents and toxins" refers to a list of over 60 substances that pose the greatest risk to public health, and China uses non-human primates to test treatment of these select agents and toxins more than the U.S. does.