| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 984,000 (2021) 3.8% of Australia's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 30.3% | |

| 5.5% | |

| 4.6% | |

| 3.9% | |

| 3.4% | |

| 2.5% | |

| 1.9% | |

| 0.9% | |

| Languages | |

| Several hundred Australian Aboriginal languages, many no longer spoken, Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Kriol | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Christian (mainly Anglican and Catholic), minority no religious affiliation, and small numbers of other religions, various local indigenous religions grounded in Australian Aboriginal mythology | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Torres Strait Islanders, Aboriginal Tasmanians, Papuans | |

Aboriginal Australians are the various First Nations peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as the peoples of Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the ethnically distinct Torres Strait Islands. The term Indigenous Australians refers to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders collectively.

Aboriginal people comprise many distinct peoples who developed across Australia for 65,000-plus years. These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history, but only in the last 200 years have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group. Aboriginal identity has changed over time and place, with family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all of varying importance.

Each group of Aboriginal peoples lived on and maintained its own country and developed sophisticated trade networks, inter-cultural relationships, law and religions.

Aboriginal people have a wide variety of cultural practices and beliefs that make up the oldest continuous cultures in the world, and have a strong connection to their country. At the time of European colonisation of Australia, they consisted of complex cultural societies with hundreds of languages and varying degrees of technology and settlements.

Contemporary Aboriginal beliefs are a complex mixture, varying by region and individual across the continent. They are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by Europeans, and contemporary issues. Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared by dancing, stories, songlines and art that collectively weave an ontology of modern daily life and ancient creation known as Dreaming.

In the past, Aboriginal people lived over large sections of the continental shelf and were isolated on many of the smaller offshore islands and Tasmania when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene inter-glacial period, about 11,700 years ago. Despite this, Aboriginal people maintained extensive networks within the continent and certain groups maintained relationships with Torres Strait Islanders and the Makassar people of modern-day Indonesia. Studies of Aboriginal groups' genetic makeup are ongoing, but evidence suggests that they have genetic inheritance from ancient Asian but not more modern peoples, and share some similarities with Papuans, but have been isolated from Southeast Asia for a very long time. Before extensive European colonisation, there were over 250 Aboriginal languages.

In the 2021 Australian Census, Indigenous Australians comprised 3.8% of Australia's population.

Most Aboriginal people today speak English and live in cities, and some may use Aboriginal phrases and words in Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Aboriginal languages in the phonology and grammatical structure). Many but not all also speak traditional languages.

Aboriginal people, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of severe health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.

Origins

The ancestors of present-day Aboriginal Australian people migrated from Southeast Asia by sea during the Pleistocene epoch and lived over large sections of the Australian continental shelf when the sea levels were lower and Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea were part of the same landmass, known as Sahul. As sea levels rose, the people on the Australian mainland and nearby islands became increasingly isolated, some on Tasmania and some of the smaller offshore islands when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene, the inter-glacial period that started about 11,700 years ago. Prehistorians believe it would have been difficult for Aboriginal people to have originated purely from mainland Asia, and not enough numbers would have made it to Australia and surrounding islands to fulfil the beginning of the population seen in the last century. This is why it is commonly believed that most Aboriginal Australians originated from Southeast Asia, and if this is the case, Aboriginal Australians were among the first in the world to complete sea voyages.

A 2017 paper in Nature evaluated artefacts in Kakadu and concluded "Human occupation began around 65,000 years ago".

A 2021 study by researchers at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage has mapped the likely migration routes of the peoples as they moved across the Australian continent to its southern reaches of what is now Tasmania, then part of the mainland. The modelling is based on data from archaeologists, anthropologists, ecologists, geneticists, climatologists, geomorphologists and hydrologists, and it is intended to compare the modelling with the oral histories of Aboriginal peoples, including Dreaming stories, Australian rock art and linguistic features of the many Aboriginal languages. The routes, dubbed "superhighways" by the authors, are similar to current highways and stock routes in Australia. Lynette Russell of Monash University sees the new model as a starting point for collaboration with Aboriginal people to help uncover their history. The new models suggest that the first people may have landed in the Kimberley region in what is now Western Australia about 60,000 years ago, and settled across the continent within 6,000 years. A 2018 study using archaeobotany dated evidence of continuous human habitation at Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen) in the Carnarvon Range in the Little Sandy Desert in WA from around 50,000 years ago.

Genetics

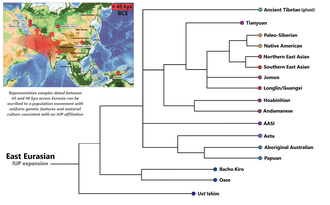

Genetic studies have revealed that Aboriginal Australians largely descended from an Eastern Eurasian population wave, and are most closely related to other Oceanians, such as Melanesians. The Aboriginal Australians also show affinity to other Australasian populations, such as Negritos or indigenous South Asian groups, such as the Andamanese people, as well as to East Asian peoples. Phylogenetic data suggests that an early initial eastern lineage (ENA) trifurcated somewhere in South Asia, and gave rise to Australasians (Oceanians), indigenous South Asians/Andamanese, and the East/Southeast Asian lineage including ancestors of the Native Americans, although Papuans may have received approximately 2% of their geneflow from an earlier group (xOOA) as well, next to additional archaic admixture in the Sahul region.

Aboriginal people are genetically most similar to the indigenous populations of Papua New Guinea, and more distantly related to groups from East Indonesia. They are more distinct from the indigenous populations of Borneo and Malaysia, sharing drift with them than compared to the groups from Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. This indicates that populations in Australia were isolated for a long time from the rest of Southeast Asia, and remained untouched by migrations and population expansions into that area, which can be explained by the Wallace line.

In a 2001 study, blood samples were collected from some Warlpiri people in the Northern Territory to study their genetic makeup (which is not representative of all Aboriginal peoples in Australia). The study concluded that the Warlpiri are descended from ancient Asians whose DNA is still somewhat present in Southeastern Asian groups, although greatly diminished. The Warlpiri DNA lacks certain information found in modern Asian genomes, and carries information not found in other genomes, reinforcing the idea of ancient Aboriginal isolation.

Genetic data extracted in 2011 by Morten Rasmussen et al., who took a DNA sample from an early-20th-century lock of an Aboriginal person's hair, found that the Aboriginal ancestors probably migrated through South Asia and Maritime Southeast Asia, into Australia, where they stayed, with the result that, outside of Africa, the Aboriginal peoples have occupied the same territory continuously longer than any other human populations. These findings suggest that modern Aboriginal Australians are the direct descendants of the eastern wave, who left Africa up to 75,000 years ago. This finding is compatible with earlier archaeological finds of human remains near Lake Mungo that date to approximately 40,000 years ago. The idea of the "oldest continuous culture" is based on the Aboriginal peoples' geographical isolation, with little or no interaction with outside cultures before some contact with Makassan fishermen and Dutch explorers up to 500 years ago.

The Rasmussen study also found evidence that Aboriginal peoples carry some genes associated with the Denisovans (a species of human related to but distinct from Neanderthals) of Asia; the study suggests that there is an increase in allele sharing between the Denisovan and Aboriginal Australian genomes, compared to other Eurasians or Africans. Examining DNA from a finger bone excavated in Siberia, researchers concluded that the Denisovans migrated from Siberia to tropical parts of Asia and that they interbred with modern humans in Southeast Asia 44,000 years BP, before Australia separated from New Guinea approximately 11,700 years BP. They contributed DNA to Aboriginal Australians along with present-day New Guineans and an indigenous tribe in the Philippines known as Mamanwa. This study makes Aboriginal Australians one of the oldest living populations in the world and possibly the oldest outside Africa, confirming they may also have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.

A 2016 study at the University of Cambridge by Christopher Klein et al. suggests that it was about 50,000 years ago that these peoples reached Sahul (the supercontinent consisting of present-day Australia and its islands and New Guinea). The sea levels rose and isolated Australia (and Tasmania) about 10,000 years ago, but Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged from each other genetically earlier, about 37,000 years BP, possibly because the remaining land bridge was impassable, and it was this isolation which makes it the world's oldest culture. The study also found evidence of an unknown hominin group, distantly related to Denisovans, with whom the Aboriginal and Papuan ancestors must have interbred, leaving a trace of about 4% in most Aboriginal Australians' genome. There is, however, increased genetic diversity among Aboriginal Australians based on geographical distribution.

Carlhoff et al. 2021 analyzed a Holocene hunter-gatherer sample ("Leang Panninge") from South Sulawesi, which shares high amounts of genetic drift with Aboriginal Australians and Papuans, which suggests to represent a population which split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans. The sample also shows genetic affinity for East Asians and Andamanese people of South Asia. The authors note that this hunter-gatherer sample can be modeled with ~50% Papuan-related ancestry and either with ~50% East Asian or Andamanese Onge ancestry, highlighting the deep split between Leang Panninge and Aboriginal/Papuans.

Two genetic studies by Larena et al. 2021 found that Philippines Negrito people split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans before they diverged from each other, but after their common ancestor diverged from the ancestor of East Asian peoples.

Changes around 4,000 years ago

The dingo reached Australia about 4,000 years ago, and around the same time there were changes in language (with the Pama-Nyungan language family spreading over most of the mainland), and in stone tool technology, with the use of smaller tools. Human contact has thus been inferred, and genetic data of two kinds have been proposed to support a gene flow from India to Australia: firstly, signs of South Asian components in Aboriginal Australian genomes, reported on the basis of genome-wide SNP data; and secondly, the existence of a Y chromosome (male) lineage, designated haplogroup C∗, with the most recent common ancestor around 5,000 years ago. The first type of evidence comes from a 2013 study by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology using large-scale genotyping data from a pool of Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, island Southeast Asians and Indians. It found that the New Guinea and Mamanwa (Philippines area) groups diverged from the Aboriginal about 36,000 years ago (and supporting evidence that these populations are descended from migrants taking an early "southern route" out of Africa, before other groups in the area), and also that the Indian and Australian populations mixed well before European contact, with this gene flow occurring during the Holocene (c. 4,200 years ago). The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those Indian genes to Aboriginal Australians, or that a group of Indians migrated all the way from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.

However, a 2016 study in Current Biology by Anders Bergström et al. excluded the Y chromosome as providing evidence for recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study authors sequenced 13 Aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes using recent advances in gene sequencing technology, investigating their divergence times from Y chromosomes in other continents, including comparing the haplogroup C chromosomes. They found a divergence time of about 54,100 years between the Sahul C chromosome and its closest relative C5, as well as about 54,300 years between haplogroups K*/M and their closest haplogroups R and Q. The deep divergence time of 50,000-plus years with the South Asian chromosome and "the fact that the Aboriginal Australian Cs share a more recent common ancestor with Papuan Cs" excludes any recent genetic contact.

The 2016 study's authors concluded that, although this does not disprove the presence of any Holocene gene flow or non-genetic influences from South Asia at that time, and the appearance of the dingo does provide strong evidence for external contacts, the evidence overall is consistent with a complete lack of gene flow, and points to indigenous origins for the technological and linguistic changes. They attributed the disparity between their results and previous findings to improvements in technology; none of the other studies had utilised complete Y chromosome sequencing, which has the highest precision. For example, use of a ten Y STRs method has been shown to massively underestimate divergence times. Gene flow across the island-dotted 150-kilometre-wide (93 mi) Torres Strait, is both geographically plausible and demonstrated by the data, although at this point it could not be determined from this study when within the last 10,000 years it may have occurred—newer analytical techniques have the potential to address such questions.

Bergstrom's 2018 doctoral thesis looking at the population of Sahul suggests that other than relatively recent admixture, the populations of the region appear to have been genetically independent from the rest of the world since their divergence about 50,000 years ago. He writes "There is no evidence for South Asian gene flow to Australia .... Despite Sahul being a single connected landmass until [8,000 years ago], different groups across Australia are nearly equally related to Papuans, and vice versa, and the two appear to have separated genetically already [about 30,000 years ago]".

Environmental adaptations

Aboriginal Australians possess inherited abilities to stand a wide range of environmental temperatures in various ways. A study in 1958 comparing cold adaptation in the desert-dwelling Pitjantjatjara people compared with a group of European people showed that the cooling adaptation of the Aboriginal group differed from that of the white people, and that they were able to sleep more soundly through a cold desert night. A 2014 Cambridge University study found that a beneficial mutation in two genes which regulate thyroxine, a hormone involved in regulating body metabolism, helps to regulate body temperature in response to fever. The effect of this is that the desert people are able to have a higher body temperature without accelerating the activity of the whole of the body, which can be especially detrimental in childhood diseases. This helps protect people to survive the side-effects of infection.

Location and demographics

Aboriginal people have lived for tens of thousands of years on the continent of Australia, through its various changes in landmass. The area within Australia's borders today includes the islands of Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt. Indigenous people of the Torres Strait Islands, however, are not Aboriginal.

In the 2016 Australian census, Indigenous Australians comprised 3.3% of Australia's population, with 91% of these identifying as Aboriginal only, 5% Torres Strait Islander, and 4% both.

Aboriginal people also live throughout the world as part of the Australian diaspora.

Languages

Most Aboriginal people speak English, with Aboriginal phrases and words being added to create Australian Aboriginal English (which also has a tangible influence of Aboriginal languages in the phonology and grammatical structure). Some Aboriginal people, especially those living in remote areas, are multi-lingual. Many of the original 250–400 Aboriginal languages (more than 250 languages and about 800 dialectal varieties on the continent) are endangered or extinct, although some efforts are being made at language revival for some. As of 2016, only 13 traditional Indigenous languages were still being acquired by children, and about another 100 spoken by older generations only.

Aboriginal Australian peoples

Dispersing across the Australian continent over time, the ancient people expanded and differentiated into distinct groups, each with its own language and culture. More than 400 distinct Australian Aboriginal peoples have been identified, distinguished by names designating their ancestral languages, dialects, or distinctive speech patterns. According to noted anthropologist, archaeologist and sociologist Harry Lourandos, historically, these groups lived in three main cultural areas, the Northern, Southern and Central cultural areas. The Northern and Southern areas, having richer natural marine and woodland resources, were more densely populated than the Central area.

Geographically-based names

There are various other names from Australian Aboriginal languages commonly used to identify groups based on geography, known as demonyms, including:

- Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Goorie (variant pronunciation and spelling of Koori) in South East Queensland and some parts of northern New South Wales

- Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria (Aboriginal Victorians)

- Murri in southern Queensland

- Nunga in southern South Australia

- Noongar in southern Western Australia

- Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania

- Tiwi on Tiwi Islands off Arnhem Land (NT)

A few examples of sub-groups

Other group names are based on the language group or specific dialect spoken. These also coincide with geographical regions of varying sizes. A few examples are:

- Anindilyakwa on Groote Eylandt (off Arnhem Land), NT

- Arrernte in central Australia

- Bininj in Western Arnhem Land (NT)

- Gunggari in south-west Queensland

- Muruwari people in New South Wales

- Luritja (Kukatja), an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Ngunnawal in the Australian Capital Territory and surrounding areas of New South Wales

- Pitjantjatjara, an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Wangai in the Western Australian Goldfields

- Warlpiri (Yapa) in western central Northern Territory

- Yamatji in central Western Australia

- Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT)

Difficulties defining groups

However, these lists are neither exhaustive nor definitive, and there are overlaps. Different approaches have been taken by non-Aboriginal scholars in trying to understand and define Aboriginal culture and societies, some focusing on the micro-level (tribe, clan, etc.), and others on shared languages and cultural practices spread over large regions defined by ecological factors. Anthropologists have encountered many difficulties in trying to define what constitutes an Aboriginal people/community/group/tribe, let alone naming them. Knowledge of pre-colonial Aboriginal cultures and societal groupings is still largely dependent on the observers' interpretations, which were filtered through colonial ways of viewing societies.

Some Aboriginal peoples identify as one of several saltwater, freshwater, rainforest or desert peoples.

Aboriginal identity

The term Aboriginal Australians includes many distinct peoples who have developed across Australia for over 50,000 years. These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history, but it is only in the last two hundred years that they have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group, socio-politically. While some preferred the term Aborigine to Aboriginal in the past, as the latter was seen to have more directly discriminatory legal origins, use of the term Aborigine has declined in recent decades, as many consider the term an offensive and racist hangover from Australia's colonial era.

The definition of the term Aboriginal has changed over time and place, with the importance of family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all being of varying importance.

The term Indigenous Australians refers to Aboriginal Australians as well as Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the term is conventionally only used when both groups are included in the topic being addressed, or by self-identification by a person as Indigenous. (Torres Strait Islanders are ethnically and culturally distinct, despite extensive cultural exchange with some of the Aboriginal groups, and the Torres Strait Islands are mostly part of Queensland but have a separate governmental status.) Some Aboriginal people object to being labelled Indigenous, as an artificial and denialist term.

Culture and beliefs

Australian Indigenous people have beliefs unique to each mob (tribe) and have a strong connection to the land. Contemporary Indigenous Australian beliefs are a complex mixture, varying by region and individual across the continent. They are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by Europeans, and contemporary issues. Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared by dancing, stories, songlines and art—especially Papunya Tula (dot painting)—collectively telling the story of creation known as The Dreamtime. Additionally, traditional healers were also custodians of important Dreaming stories as well as their medical roles (for example the Ngangkari in the Western desert). Some core structures and themes are shared across the continent with details and additional elements varying between language and cultural groups. For example, in The Dreamtime of most regions, a spirit creates the earth then tells the humans to treat the animals and the earth in a way which is respectful to land. In Northern Territory this is commonly said to be a huge snake or snakes that weaved its way through the earth and sky making the mountains and oceans. But in other places the spirits who created the world are known as wandjina rain and water spirits. Major ancestral spirits include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, Dirawong and Bunjil. Similarly, the Arrernte people of central Australia believed that humanity originated from great superhuman ancestors who brought the sun, wind and rain as a result of breaking through the surface of the Earth when waking from their slumber.

Health and disadvantage

Aboriginal Australians, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.

Due to the aforementioned disadvantage, Aboriginal Australian communities experience a higher rate of suicide, as compared to non-indigenous communities. These issues stem from a variety of different causes unique to indigenous communities, such as historical trauma, socioeconomic disadvantage, and decreased access to education and health care. Also, this problem largely affects indigenous youth, as many indigenous youth may feel disconnected from their culture.

To combat the increased suicide rate, many researchers have suggested that the inclusion of more cultural aspects into suicide prevention programs would help to combat mental health issues within the community. Past studies have found that many indigenous leaders and community members, do in fact, want more culturally-aware health care programs. Similarly, culturally-relative programs targeting indigenous youth have actively challenged suicide ideation among younger indigenous populations, with many social and emotional wellbeing programs using cultural information to provide coping mechanisms and improving mental health.

Viability of remote communities

The outstation movement of the 1970s and 1980s, when Aboriginal people moved to tiny remote settlements on traditional land, brought health benefits, but funding them proved expensive, training and employment opportunities were not provided in many cases, and support from governments dwindled in the 2000s, particularly in the era of the Howard government.

Indigenous communities in remote Australia are often small, isolated towns with basic facilities, on traditionally owned land. These communities have between 20 and 300 inhabitants and are often closed to outsiders for cultural reasons. The long-term viability and resilience of Aboriginal communities in desert areas has been discussed by scholars and policy-makers. A 2007 report by the CSIRO stressed the importance of taking a demand-driven approach to services in desert settlements, and concluded that "if top-down solutions continue to be imposed without appreciating the fundamental drivers of settlement in desert regions, then those solutions will continue to be partial, and ineffective in the long term".