| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1984 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Dissolved | 1993 (renamed) |

| Superseding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the "Star Wars program", was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (intercontinental ballistic missiles and submarine-launched ballistic missiles). The concept was announced on March 23, 1983, by President Ronald Reagan, a vocal critic of the doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD), which he described as a "suicide pact". Reagan called upon American scientists and engineers to develop a system that would render nuclear weapons obsolete. Elements of the program reemerged in 2019 with the Space Development Agency (SDA).

The Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO) was set up in 1984 within the US Department of Defense to oversee development. A wide array of advanced weapon concepts, including lasers, particle beam weapons and ground- and space-based missile systems were studied, along with various sensor, command and control, and high-performance computer systems that would be needed to control a system consisting of hundreds of combat centers and satellites spanning the entire globe and involved in a very short battle. The United States holds a significant advantage in the field of comprehensive advanced missile defense systems through decades of extensive research and testing; a number of these concepts and obtained technologies and insights were transferred to subsequent programs.

Under the SDIO's Innovative Sciences and Technology Office, headed by physicist and engineer Dr. James Ionson, the investment was predominantly made in basic research at national laboratories, universities, and in industry; these programs have continued to be key sources of funding for top research scientists in the fields of high-energy physics, supercomputing/computation, advanced materials, and many other critical science and engineering disciplines and funding which indirectly supports other research work by top scientists.

In 1987, the American Physical Society concluded that the technologies being considered were decades away from being ready for use, and at least another decade of research was required to know whether such a system was even possible. After the publication of the APS report, SDI's budget was repeatedly cut. By the late 1980s, the effort had been re-focused on the "Brilliant Pebbles" concept using small orbiting missiles not unlike a conventional air-to-air missile, which was expected to be much less expensive to develop and deploy.

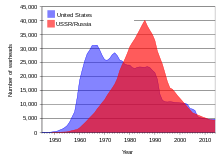

SDI was controversial in some sectors, and was criticized for threatening to destabilize the MAD-approach potentially rendering the Soviet nuclear arsenal useless and to possibly re-ignite "an offensive arms race". Through declassified papers of American intelligence agencies the wider implications and effects of the program were examined and revealed that due to the potential neutralization of its arsenal and resulting loss of a balancing power factor, SDI was a cause of grave concern for the Soviet Union and her primary successor state Russia. By the early 1990s, with the Cold War ending and nuclear arsenals being rapidly reduced, political support for SDI collapsed. SDI officially ended in 1993, when the Clinton Administration redirected the efforts towards theatre ballistic missiles and renamed the agency the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO).

In 2019, space-based interceptor development resumed for the first time in 25 years with President Trump's signing of the National Defense Authorization Act. The program is currently managed by the Space Development Agency (SDA) as part of the new National Defense Space Architecture (NDSA) envisioned by Michael D. Griffin. Early development contracts were awarded to L3Harris and SpaceX. CIA Director Mike Pompeo called for additional funding to achieve a full-fledged "Strategic Defense Initiative for our time, the SDI II".

History

National BMD

The US Army had considered the issue of ballistic missile defense (BMD) as early as the end of World War II. Studies on the topic suggested attacking a V-2 rocket would be difficult because the flight time was so short that it would leave little time to forward information through command and control networks to the missile batteries that would attack them. Bell Labs pointed out that although longer-range missiles flew much faster, their longer flight times would address the timing issue and their very high altitudes would make long-range detection by radar easier.

This led to a series of projects including Nike Zeus, Nike-X, Sentinel and ultimately the Safeguard Program, all aimed at deploying a nationwide defensive system against attacks by Soviet ICBMs. The reason for so many programs was the rapidly changing strategic threat; the Soviets claimed to be producing missiles "like sausages", and ever-more missiles would be needed to defend against this growing fleet. Low-cost countermeasures like radar decoys required additional interceptors to counter. An early estimate suggested one would have to spend $20 on defense for every $1 the Soviets spent on offense. The addition of MIRV in the late 1960s further upset the balance in favor of offense systems. This cost-exchange ratio was so favorable that it appeared the only thing building a defense would do would be to cause an arms race.

When initially faced with this problem, Dwight D. Eisenhower asked ARPA to consider alternative concepts. Their Project Defender studied all sorts of systems, before abandoning most of them to concentrate on Project BAMBI. BAMBI used a series of satellites carrying interceptor missiles that would attack the Soviet ICBMs shortly after launch. This boost phase intercept rendered MIRV impotent; a successful attack would destroy all of the warheads. Unfortunately, the operational cost of such a system would be enormous, and the US Air Force continually rejected such concepts. Development was cancelled in 1963.

Through this period, the entire topic of BMD became increasingly controversial. Early deployment plans were met with little interest, but by the late 1960s, public meetings on the Sentinel system were met by thousands of angry protesters. After thirty years of effort, only one such system would be built; a single base of the original Safeguard system became operational in April 1975, only to shut down in February 1976.

A Soviet military A-35 anti-ballistic missile system was deployed around Moscow to intercept enemy ballistic missiles targeting the city or its surrounding areas. The A-35 was the only Soviet ABM system allowed under the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. In development since the 1960s and in operation from 1971 until the 1990s, it featured the nuclear-tipped A350 exoatmospheric interceptor missile.

Lead up to SDI

George Shultz, Reagan's secretary of state, suggested that a 1967 lecture by physicist Edward Teller (the so-called "father of the hydrogen bomb") was an important precursor to SDI. In the lecture, Teller talked about the idea of defending against nuclear missiles using nuclear weapons, principally the W65 and W71, with the latter being a contemporary enhanced thermal/X-ray device used actively on the Spartan missile in 1975. Held at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), the 1967 lecture was attended by Reagan shortly after he became the governor of California.

Development of laser weapons in the Soviet Union began in 1964–1965. Though classified at the time, a detailed study on a Soviet space-based laser system began no later than 1976 with the Polyus, a 1 MW Carbon dioxide laser-based orbital weapons platform prototype. Development was also started on the anti-satellite system Kaskad, an in-orbit missile platform.

A revolver cannon (Rikhter R-23) was mounted on the 1974 Soviet Salyut 3 space station, a satellite that successfully test fired its cannon in orbit.

In 1979, Teller contributed to a Hoover Institution publication where he claimed that the US would be facing an emboldened USSR due to their work on civil defense. Two years later at a conference in Italy, he made the same claims about their ambitions, but with a subtle change; now he claimed that the reason for their boldness was their development of new space-based weapons. According to the popular opinion at the time, and one shared by author Frances FitzGerald; there was absolutely no evidence that such research was being carried out. What had really changed was that Teller was now selling his latest nuclear weapon, the X-ray laser. Finding limited success in his efforts to get funding for the project, his speech in Italy was a new attempt to create a missile gap.

In 1979, Reagan visited the NORAD command base, Cheyenne Mountain Complex, where he was first introduced to the extensive tracking and detection systems extending throughout the world and into space; however, he was struck by their comments that while they could track the attack down to the individual targets, there was nothing one could do to stop it. Reagan felt that in the event of an attack this would place the president in a terrible position, having to choose between immediate counterattack or attempting to absorb the attack and then maintain an upper hand in the post-attack era. Shultz suggests that this feeling of helplessness, coupled with the defensive ideas proposed by Teller a decade earlier, combined to form the impetus of the SDI.

In the fall of 1979, at Reagan's request, Lieutenant General Daniel O. Graham, the former head of the DIA, briefed Reagan on an updated BAMBI he called High Frontier, a missile shield composed of multi-layered ground- and space-based weapons that could track, intercept, and destroy ballistic missiles, which would theoretically be possible because of emerging technologies. It was designed to replace the MAD doctrine that Reagan and his aides described as a suicide pact. In September 1981, Graham formed a small, Virginia-based think tank called High Frontier to continue research on the missile shield. The Heritage Foundation provided High Frontier with space to conduct research, and Graham published a 1982 report entitled, "High Frontier: A New National Strategy" that examined in greater detail how the system would function.

Graham was not alone in considering the anti-missile problem. Since the late 1970s, a group had been pushing for the development of a high-powered chemical laser that would be placed in orbit and attack ICBMs, the Space Based Laser (SBL). More recently, new developments under Project Excalibur by Teller's "O-Group" at LLNL suggested that a single X-ray laser could shoot down dozens of missiles with a single shot. Graham organized a meeting space at The Heritage Foundation in Washington and the groups began to meet in order to present their plans to the incoming president.

The group met with Reagan several times during 1981 and 1982, apparently with little effect, while the buildup of new offensive weaponry like the B-1 Lancer and MX missile continued; however, in early 1983, the Joint Chiefs of Staff met with the president and outlined the reasons why they might consider shifting some of the funding from the offensive side to new defensive systems.

According to a 1983 US Interagency Intelligence Assessment, there was good evidence that in the late 1960s the Soviets were devoting serious thought to both explosive and non-explosive nuclear power sources for lasers.

Project and proposals

Announcement

On March 23, 1983, Reagan announced SDI in a nationally televised speech, stating "I call upon the scientific community in this country, those who gave us nuclear weapons, to turn their great talents to the cause of mankind and world peace, to give us the means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete."

Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO)

In 1984, the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO) was established to oversee the program, which was headed by Lt. General James Alan Abrahamson USAF, a past Director of the NASA Space Shuttle program.

In addition to the ideas presented by the original Heritage group, a number of other concepts were also considered. Notable among these were particle-beam weapons, updated versions of nuclear shaped charges, and various plasma weapons. Additionally, the SDIO invested in computer systems, component miniaturization, and sensors.

Initially, the program focused on large scale systems designed to defeat a massive Soviet offensive strike. For this mission, SDIO concentrated almost entirely on the "high tech" solutions like lasers. Graham's proposal was repeatedly rejected by members of the Heritage group as well as within SDIO; when asked about it in 1985, Abrahamson suggested that the concept was underdeveloped and was not being considered.

By 1986, many of the promising ideas were failing. Teller's X-ray laser, run under Project Excalibur, failed several key tests in 1986 and was soon being suggested solely for the anti-satellite role. The particle beam concept was demonstrated to basically not work, as was the case with several other concepts. Only the Space Based Laser seemed to have any hope of developing in the short term, but it was growing in size due to its fuel consumption.

APS report

The American Physical Society (APS) had been asked by the SDIO to provide a review of the various concepts. They put together an all-star panel including many of the inventors of the laser, one of which was a Nobel laureate. Their initial report was presented in 1986, but due to classification issues it was not released to the public (in redacted form) until early 1987.

The report considered all of the systems then under development, and concluded none of them were anywhere near ready for deployment. Specifically, they noted that all of the systems had to improve their energy output by at least 100 times, and in some cases as much as a million. In other cases, like Excalibur, they dismissed the concept entirely. Their summary stated simply:

We estimate that all existing candidates for directed energy weapons (DEWs) require two or more orders of magnitude, (powers of 10) improvements in power output and beam quality before they may be seriously considered for application in ballistic missile defense systems.

In a best case scenario, they concluded that none of the systems could be deployed as an anti-missile system until into the next century.

Strategic Defense System

Faced with this report, and the press storm that followed, the SDIO changed direction. Beginning in late 1986, Abrahamson proposed that SDI would be based on the system he had previously dismissed, a version of High Frontier now renamed the "Strategic Defense System, Phase I Architecture". The name implied that the concept would be replaced by more advanced systems in future phases.

Strategic Defense System, or SDS, was largely the Smart Rocks concept with an added layer of ground-based missiles in the US. These missiles were intended to attack the enemy warheads that the Smart Rocks had missed. In order to track them when they were below the radar horizon, SDS also added a number of additional satellites flying at low altitude that would feed tracking information to both the space-based "garages" as well as the ground-based missiles. The ground-based systems operational today trace their roots back to this concept.

While SDS was being proposed, Lawrence Livermore National had introduced a new concept known as Brilliant Pebbles. This was essentially the combination of the sensors on the garage satellites and the low-orbit tracking stations on the Smart Rocks missile. Advancements in new sensors and microprocessors allowed all of this to be packaged into the volume of a small missile nose cone. Over the next two years, a variety of studies suggested that this approach would be cheaper, easier to launch and more resistant to counterattack, and in 1990 Brilliant Pebbles was selected as the baseline model for the SDS Phase 1.

Global Protection Against Limited Strikes (GPALS)

While SDIO and SDS was ongoing, the Warsaw Pact was rapidly disintegrating, culminating in the destruction of the Berlin Wall in 1989. One of the many reports on SDS considered these events, and suggested that the massive defense against a Soviet launch would soon be unnecessary, but that short and medium range missile technology would likely proliferate as the former Soviet Union disintegrated and sold off their hardware. One of the core ideas behind the GPALS system was that the Soviet Union would not always be assumed as the aggressor and the United States would not always be assumed as the target.

Instead of a heavy defense aimed at ICBMs, this report suggested realigning the deployment for the Global Protection Against Limited Strikes (GPALS). Against such threats the Brilliant Pebbles would have limited performance, largely because the missiles fired for only a short period and the warheads did not rise high enough for them to be easily tracked by a satellite above them. To the original SDS, GPALS added a new mobile ground-based missile, and added more low-orbit satellites known as Brilliant Eyes to feed information to the Pebbles.

GPALS was approved by President George H.W. Bush in 1991. The new system would cut the proposed costs of the SDI system from $53 billion to $41 billion over a decade. Also, instead of making plans to protect against thousands of incoming missiles, the GPALS system sought to provide flawless protection from up to two hundred nuclear missiles. The GPALS system also was able to protect the United States from attacks coming from all different parts of the world.

Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO)

In 1993, the Clinton administration further shifted the focus to ground-based interceptor missiles and theater scale systems, forming the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO) and closing the SDIO. The Ballistic Missile Defense Organization was renamed again by the George W. Bush administration as the Missile Defense Agency and focused onto limited National Missile Defense.

Ground-based programs

Extended Range Interceptor (ERINT)

The Extended Range Interceptor (ERINT) program was part of SDI's Theater Missile Defense Program and was an extension of the Flexible Lightweight Agile Guided Experiment (FLAGE), which included developing hit-to-kill technology and demonstrating the guidance accuracy of a small, agile, radar-homing vehicle.

FLAGE scored a direct hit against a MGM-52 Lance missile in flight, at White Sands Missile Range in 1987. ERINT was a prototype missile similar to the FLAGE, but it used a new solid-propellant rocket motor that allowed it to fly faster and higher than FLAGE.

Under BMDO, ERINT was later chosen as the MIM-104 Patriot (Patriot Advanced Capability-3,PAC-3) missile.

Homing Overlay Experiment (HOE)

Given concerns about the previous programs using nuclear-tipped interceptors, in the 1980s the US Army began studies about the feasibility of hit-to-kill vehicles, i.e. interceptor missiles that would destroy incoming ballistic missiles just by colliding with them head-on.

The Homing Overlay Experiment (HOE) was the first hit-to-kill system tested by the US Army, and also the first successful hit-to-kill intercept of a mock ballistic missile warhead outside the Earth's atmosphere.

The HOE used a kinetic kill vehicle (KKV) to destroy a ballistic missile. The KKV was equipped with an infrared seeker, guidance electronics and a propulsion system. Once in space, the KKV could extend a folded structure similar to an umbrella skeleton of 4 m (13 ft) diameter to enhance its effective cross section. This device would destroy the ICBM reentry vehicle on collision.

Four test launches were conducted in 1983 and 1984 at Kwajalein Missile Range in the Marshall Islands. For each test a Minuteman missile was launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California carrying a single mock re-entry vehicle targeted for Kwajalein lagoon more than 4,000 miles (6,400 km) away.

After test failures with the first three flight tests because of guidance and sensor problems, the DOD reported that the fourth and final test on June 10, 1984, was successful, intercepting the Minuteman RV with a closing speed of about 6.1 km/s at an altitude of more than 160 km (99 mi).

Although the fourth test was described as a success, the New York Times in August 1993 reported that the HOE4 test was rigged to increase the likelihood of a successful hit. At the urging of Senator David Pryor, the General Accounting Office investigated the claims and concluded that though steps were taken to make it easier for the interceptor to find its target (including some of those alleged by the New York Times), the available data indicated that the interceptor had been successfully guided by its onboard infrared sensors in the collision, and not by an onboard radar guidance system as alleged. Per the GAO report, the net effect of the DOD enhancements increased the infrared signature of the target vessel by 110% over the realistic missile signature initially proposed for the HOE program, but nonetheless the GAO concluded the enhancements to the target vessel were reasonable given the objectives of the program and the geopolitical consequences of its failure. Further, the report concluded that the DOD's subsequent statements before Congress about the HOE program "fairly characterize[d]" the success of HOE4, but confirmed that the DOD never disclosed to Congress the enhancements made to the target vessel.

The technology developed for the HOE system was later used by the SDI and expanded into the Exoatmospheric Reentry-vehicle Interception System (ERIS) program.

ERIS and HEDI

Developed by Lockheed as part of the ground-based interceptor portion of SDI, the Exoatmospheric Reentry-vehicle Interceptor Subsystem (ERIS) began in 1985, with at least two tests occurring in the early 1990s. This system was never deployed, but the technology of the system was used in the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system and the Ground-Based Interceptor currently deployed as part of the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system.

Directed-energy weapon (DEW) programs

X-ray laser

An early focus of the SDI effort was an X-ray lasers powered by nuclear explosions. Nuclear explosions give off a huge burst of X-rays, which the Excalibur concept intended to focus using a lasing medium consisting of metal rods. Many such rods would be placed around a warhead, each one aimed at a different ICBM, thus destroying many ICBMs in a single attack. It would cost much less for the US to build another Excalibur than the Soviets would need to build enough new ICBMs to counter it. The idea was first based on satellites, but when it was pointed out that these could be attacked in space, the concept moved to a "pop-up" concept, rapidly launched from a submarine off the Soviet northern coast.

However, on March 26, 1983, the first test, known as the Cabra event, was performed in an underground shaft and resulted in marginally positive readings that could be dismissed as being caused by a faulty detector. Since a nuclear explosion was used as the power source, the detector was destroyed during the experiment and the results therefore could not be confirmed. Technical criticism based upon unclassified calculations suggested that the X-ray laser would be of at best marginal use for missile defense. Such critics often cite the X-ray laser system as being the primary focus of SDI, with its apparent failure being a main reason to oppose the program; however, the laser was never more than one of the many systems being researched for ballistic missile defense.

Despite the apparent failure of the Cabra test, the long term legacy of the X-ray laser program is the knowledge gained while conducting the research. A parallel developmental program advanced laboratory X-ray lasers for biological imaging and the creation of 3D holograms of living organisms. Other spin-offs include research on advanced materials like SEAgel and Aerogel, the Electron-Beam Ion Trap facility for physics research, and enhanced techniques for early detection of breast cancer.

Chemical laser

Beginning in 1985, the Air Force tested an SDIO-funded deuterium fluoride laser known as Mid-Infrared Advanced Chemical Laser (MIRACL) at White Sands Missile Range. During a simulation, the laser successfully destroyed a Titan missile booster in 1985, however the test setup had the booster shell pressurized and under considerable compression loads. These test conditions were used to simulate the loads a booster would be under during launch. The system was later tested on target drones simulating cruise missiles for the US Navy, with some success. After the SDIO closed, the MIRACL was tested on an old Air Force satellite for potential use as an anti-satellite weapon, with mixed results. The technology was also used to develop the Tactical High Energy Laser, (THEL) which is being tested to shoot down artillery shells.

During the mid-to-late 1980s a number of panel discussions on lasers and SDI took place at various laser conferences. Proceedings of these conferences include papers on the status of chemical and other high power lasers at the time.

The Missile Defense Agency's Airborne Laser program uses a chemical laser which has successfully intercepted a missile taking off, so an offshoot of SDI could be said to have successfully implemented one of the key goals of the program.

Neutral particle beam

In July 1989, the Beam Experiments Aboard a Rocket (BEAR) program launched a sounding rocket containing a neutral particle beam (NPB) accelerator. The experiment successfully demonstrated that a particle beam would operate and propagate as predicted outside the atmosphere and that there are no unexpected side-effects when firing the beam in space. After the rocket was recovered, the particle beam was still operational. According to the BMDO, the research on neutral particle beam accelerators, which was originally funded by the SDIO, could eventually be used to reduce the half-life of nuclear waste products using accelerator-driven transmutation technology.

Laser and mirror experiments

The High Precision Tracking Experiment (HPTE), launched with the Space Shuttle Discovery on STS-51-G, was tested June 21, 1985, when a Hawaii-based low-power laser successfully tracked the experiment and bounced the laser off of the HPTE mirror.

The Relay mirror experiment (RME), launched in February 1990, demonstrated critical technologies for space-based relay mirrors that would be used with an SDI directed-energy weapon system. The experiment validated stabilization, tracking, and pointing concepts and proved that a laser could be relayed from the ground to a 60 cm mirror on an orbiting satellite and back to another ground station with a high degree of accuracy and for extended durations.

Launched on the same rocket as the RME, the Low-power Atmospheric Compensation Experiment (LACE) satellite was built by the United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) to explore atmospheric distortion of lasers and real-time adaptive compensation for that distortion. The LACE satellite also included several other experiments to help develop and improve SDI sensors, including target discrimination using background radiation and tracking ballistic missiles using Ultraviolet Plume Imaging (UVPI). LACE was also used to evaluate ground-based adaptive optics, a technique now used in civilian telescopes to remove atmospheric distortions.

Hypervelocity Railgun (CHECMATE)

Research out of hypervelocity railgun technology was done to build an information base about railguns so that SDI planners would know how to apply the technology to the proposed defense system. The SDI railgun investigation, called the Compact High Energy Capacitor Module Advanced Technology Experiment, had been able to fire two projectiles per day during the initiative. This represented a significant improvement over previous efforts, which were only able to achieve about one shot per month. Hypervelocity railguns are, at least conceptually, an attractive alternative to a space-based defense system because of their envisioned ability to quickly shoot at many targets. Also, since only the projectile leaves the gun, a railgun system can potentially fire many times before needing to be resupplied.

A hypervelocity railgun works very much like a particle accelerator in so far as it converts electrical potential energy into kinetic energy imparted to the projectile. A conductive pellet (the projectile) is attracted down the rails by electric current flowing through a rail. Through the magnetic forces that this system achieves, a force is exerted on the projectile moving it down the rail. Railguns can generate muzzle-velocities in excess of 2.4 kilometers per second.

Railguns face a host of technical challenges before they will be ready for battlefield deployment. First, the rails guiding the projectile must carry very high power. Each firing of the railgun produces tremendous current flow (almost half a million amperes) through the rails, causing rapid erosion of the rail's surfaces (through ohmic heating), and even vaporization of the rail surface. Early prototypes were essentially single-use weapons, requiring complete replacement of the rails after each firing. Another challenge with the railgun system is projectile survivability. The projectiles experience acceleration force in excess of 100,000 g. To be effective, the fired projectile must first survive the mechanical stress of firing and the thermal effects of a trip through the atmosphere at many times the speed of sound before its subsequent impact with the target. In-flight guidance, if implemented, would require the onboard navigation system to be built to the same level of sturdiness as the main mass of the projectile.

In addition to being considered for destroying ballistic missile threats, railguns were also being planned for service in space platform (sensor and battle station) defense. This potential role reflected defense planner expectations that the railguns of the future would be capable of not only rapid fire, but also of multiple firings (on the order of tens to hundreds of shots).

Space-based programs

Space-Based Interceptor (SBI)

Groups of interceptors were to be housed in orbital modules. Hover testing was completed in 1988 and demonstrated integration of the sensor and propulsion systems in the prototype SBI. It also demonstrated the ability of the seeker to shift its aiming point from a rocket's hot plume to its cool body, a first for infrared ABM seekers. Final hover testing occurred in 1992 using miniaturized components similar to what would have actually been used in an operational interceptor. These prototypes eventually evolved into the Brilliant Pebbles program.

Brilliant Pebbles

Brilliant Pebbles was a non-nuclear system of satellite-based interceptors designed to use high-velocity, watermelon-sized, teardrop-shaped projectiles made of tungsten as kinetic warheads. It was designed to operate in conjunction with the Brilliant Eyes sensor system. The project was conceived in November 1986 by Lowell Wood at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Detailed studies were undertaken by several advisory boards, including the Defense Science Board and JASON, in 1989.

The Pebbles were designed in such a way that autonomous operation, without further external guidance from planned SDI sensor systems, was possible. This was attractive as a cost saving measure, as it would allow scaling back of those systems, and was estimated to save $7 to $13 billion versus the standard Phase I Architecture. Brilliant Pebbles later became the centerpiece of a revised architecture under the Bush Administration SDIO.

John H. Nuckolls, director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory from 1988 to 1994, described the system as "The crowning achievement of the Strategic Defense Initiative". Some of the technologies developed for SDI were used in numerous later projects. For example, the sensors and cameras that were developed and manufactured for Brilliant Pebbles systems became components of the Clementine mission and SDI technologies may also have a role in future missile defense efforts.

Though regarded as one of the most capable SDI systems, the Brilliant Pebbles program was canceled in 1994 by the BMDO.

Sensor programs

SDIO sensor research encompassed visible light, ultraviolet, infrared, and radar technologies, and eventually led to the Clementine mission though that mission occurred just after the program transitioned to the BMDO. Like other parts of SDI, the sensor system initially was very large-scale, but after the Soviet threat diminished it was cut back.

Boost Surveillance and Tracking System (BSTS)

Boost Surveillance and Tracking System was part of the SDIO in the late 1980s, and was designed to assist detection of missile launches, especially during the boost phase; however, once the SDI program shifted toward theater missile defense in the early 1990s, the system left SDIO control and was transferred to the Air Force.

Space Surveillance and Tracking System (SSTS)

Space Surveillance and Tracking System was a system originally designed for tracking ballistic missiles during their mid-course phase. It was designed to work in conjunction with BSTS, but was later scaled down in favor of the Brilliant Eyes program.

Brilliant Eyes

Brilliant Eyes was a simpler derivative of the SSTS that focused on theater ballistic missiles rather than ICBMs and was meant to operate in conjunction with the Brilliant Pebbles system.

Brilliant Eyes was renamed Space and Missile Tracking System (SMTS) and scaled back further under BMDO, and in the late 1990s it became the low earth orbit component of the Air Force's Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS).

Other sensor experiments

The Delta 183 program used a satellite known as Delta Star to test several sensor related technologies. Delta Star carried a thermographic camera, a long-wave infrared imager, an ensemble of imagers and photometers covering several visible and ultraviolet bands as well as a laser detector and ranging device. The satellite observed several ballistic missile launches including some releasing liquid propellant as a countermeasure to detection. Data from the experiments led to advances in sensor technologies.

Countermeasures

In war-fighting, countermeasures can have a variety of meanings:

- The immediate tactical action to reduce vulnerability, such as chaff, decoys, and maneuvering.

- Counter strategies which exploit a weakness of an opposing system, such as adding more MIRV warheads which are less expensive than the interceptors fired against them.

- Defense suppression. That is, attacking elements of the defensive system.

Countermeasures of various types have long been a key part of warfighting strategy; however, with SDI they attained a special prominence due to the system cost, scenario of a massive sophisticated attack, strategic consequences of a less-than-perfect defense, outer spacebasing of many proposed weapons systems, and political debate.

Whereas the current United States national missile defense system is designed around a relatively limited and unsophisticated attack, SDI planned for a massive attack by a sophisticated opponent. This raised significant issues about economic and technical costs associated with defending against anti-ballistic missile defense countermeasures used by the attacking side.

For example, if it had been much cheaper to add attacking warheads than to add defenses, an attacker of similar economic power could have simply outproduced the defender. This requirement of being "cost effective at the margin" was first formulated by Paul Nitze in November 1985.

In addition, SDI envisioned many space-based systems in fixed orbits, ground-based sensors, command, control and communications facilities, etc. In theory, an advanced opponent could have targeted those, in turn requiring self-defense capability or increased numbers to compensate for attrition.

A sophisticated attacker having the technology to use decoys, shielding, maneuvering warheads, defense suppression, or other countermeasures would have multiplied the difficulty and cost of intercepting the real warheads. SDI design and operational planning had to factor in these countermeasures and the associated cost.

Response from the Soviet Union

SDI failed to dissuade the USSR from investing in development of ballistic missiles. The Soviet response to the SDI during the period of March 1983 through November 1985 provided indications of their view of the program both as a threat and as an opportunity to weaken NATO. SDI was likely seen not only as a threat to the physical security of the Soviet Union, but also as part of an effort by the United States to seize the strategic initiative in arms controls by neutralizing the military component of Soviet strategy. The Kremlin expressed concerns that space-based missile defenses would make nuclear war inevitable.

A major objective of that strategy was the political separation of Western Europe from the United States, which the Soviets sought to facilitate by aggravating allied concern over the SDI's potential implications for European security and economic interests. The Soviet predisposition to see deception behind the SDI was reinforced by their assessment of US intentions and capabilities and the utility of military deception in furthering the achievement of political goals.

In 1986 Carl Sagan summarized what he heard Soviet commentators were saying about SDI, with a common argument being that it was equivalent to starting an economic war through a defensive arms race to further cripple the Soviet economy with extra military spending, while another interpretation was that it served as a disguise for the US wish to initiate a first strike on the Soviet Union.

Though classified at the time, a detailed study on a Soviet space-based LASER system began no later than 1976 as the Skif, a 1 MW Carbon dioxide laser along with the anti-satellite Kaskad, an in-orbit missile platform. With both devices reportedly designed to pre-emptively destroy any US satellites that might be launched in the future which could otherwise aid US missile defense.

Terra-3 was a Soviet laser testing centre, located on the Sary Shagan anti-ballistic missile (ABM) testing range in the Karaganda Region of Kazakhstan. It was originally built to test missile defense concepts, In 1984, officials within the United States Department of Defense (DoD) suggested it was the site of a prototypical anti-satellite weapon system.

In 1987 a disguised Mir space station module was lifted on the inaugural flight of the Energia booster as the Polyus and it has since been revealed that this craft housed a number of systems of the Skif laser, which were intended to be clandestinely tested in orbit, if it had not been for the spacecraft's attitude control system malfunctioning upon separation from the booster and it failing to reach orbit. More tentatively, it is also suggested that the Zarya module of the International Space Station, capable of station keeping and providing sizable battery power, was initially developed to power the Skif laser system.

The polyus was a prototype of the Skif orbital weapons platform designed to destroy Strategic Defense Initiative satellites with a megawatt carbon-dioxide laser. Soviet motivations behind attempting to launch components of the Skif laser in the form of Polyus were, according to interviews conducted years later, more for propaganda purposes in the prevailing climate of focus on US SDI, than as an effective defense technology, as the phrase "Space based laser" has a certain political capital.

In 2014, a declassified CIA paper states that "In response to SDI, Moscow threatened a variety of military countermeasures in lieu of developing a parallel missile defense system".

Controversy and criticism

Historians from the Missile Defense Agency attribute the term "Star Wars" to a Washington Post article published March 24, 1983, the day after the speech, which quoted Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy describing the proposal as "reckless Star Wars schemes", a reference to the fantasy franchise Star Wars. Some critics used the term derisively, implying it was an impractical science fiction. In addition, the American media's liberal use of the moniker (despite President Reagan's request that they use the program's official name) did much to damage the program's credibility. In comments to the media on March 7, 1986, Acting Deputy Director of SDIO, Dr. Gerold Yonas, described the name "Star Wars" as an important tool for Soviet disinformation and asserted that the nickname gave an entirely wrong impression of SDI.

Jessica Savitch reported on the technology in episode No.111 of Frontline, "Space: The Race for High Ground" on PBS on November 4, 1983. The opening sequence shows Jessica Savitch seated next to a laser that she used to destroy a model of a communication satellite. The demonstration was perhaps the first televised use of a weapons grade laser. No theatrical effects were used. The model was actually destroyed by the heat from the laser. The model and the laser were realized by Marc Palumbo, a High Tech Romantic artist from the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT.

Ashton Carter, then a board member at MIT, assessed SDI for Congress in 1984, saying there were a number of difficulties in creating an adequate missile defense shield, with or without lasers. Carter said X-rays have a limited scope because they become diffused through the atmosphere, much like the beam of a flashlight spreading outward in all directions. This means the X-rays needed to be close to the Soviet Union, especially during the critical few minutes of the booster phase, for the Soviet missiles to be both detectable to radar and targeted by the lasers themselves. Opponents disagreed, saying advances in technology, such as using very strong laser beams, and by "bleaching" the column of air surrounding the laser beam, could increase the distance that the X-ray would reach to successfully hit its target.

Physicists Hans Bethe and Richard Garwin, who worked with Edward Teller on both the atomic bomb and hydrogen bomb at Los Alamos, claimed a laser defense shield was unfeasible. They said that a defensive system was costly and difficult to build yet simple to destroy, and claimed that the Soviets could easily use thousands of decoys to overwhelm it during a nuclear attack. They believed that the only way to stop the threat of nuclear war was through diplomacy and dismissed the idea of a technical solution to the Cold War, saying that a defense shield could be viewed as threatening because it would limit or destroy Soviet offensive capabilities while leaving the American offense intact. In March 1984, Bethe coauthored a 106-page report for the Union of Concerned Scientists that concluded "the X-ray laser offers no prospect of being a useful component in a system for ballistic missile defense."

In response to this when Teller testified before Congress he stated that "instead of [Bethe] objecting on scientific and technical grounds, which he thoroughly understands, he now objects on the grounds of politics, on grounds of military feasibility of military deployment, on other grounds of difficult issues which are quite outside the range of his professional cognizance or mine."

On June 28, 1985, David Lorge Parnas resigned from SDIO's Panel on Computing in Support of Battle Management, arguing in eight short papers that the software required by the Strategic Defense Initiative could never be made to be trustworthy and that such a system would inevitably be unreliable and constitute a menace to humanity in its own right. Parnas said he joined the panel with the desire to make nuclear weapons "impotent and obsolete" but soon concluded that the concept was "a fraud".

Treaty obligations

Another criticism of SDI was that it would require the United States to modify previously ratified treaties. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which requires "States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner" and would forbid the US from pre-positioning in Earth orbit any devices powered by nuclear weapons and any devices capable of "mass destruction". Only the space stationed nuclear pumped X-ray laser concept would have violated this treaty, since other SDI systems, did not require the pre-positioning of nuclear explosives in space.

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and its subsequent protocol, which limited missile defenses to one location per country at 100 missiles each (which the USSR had and the US did not), would have been violated by SDI ground-based interceptors. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty requires "Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control." Many viewed favoring deployment of ABM systems as an escalation rather than cessation of the nuclear arms race, and therefore a violation of this clause. On the other hand, many others did not view SDI as an escalation.

SDI and MAD

SDI was criticized for potentially disrupting the strategic stability afforded by the doctrine of mutual assured destruction. MAD postulated that intentional nuclear attack was inhibited by the certainty of ensuing mutual destruction. Even if a nuclear first strike destroyed many of the opponent's weapons, sufficient nuclear missiles would survive to render a devastating counter-strike against the attacker. The criticism was that SDI could have potentially allowed an attacker to survive the lighter counter-strike, thus encouraging a first strike by the side having SDI. Another destabilizing scenario was countries being tempted to strike first before SDI was deployed, thereby avoiding a disadvantaged nuclear posture. Proponents of SDI argued that SDI development might instead cause the side that did not have the resources to develop SDI to, rather than launching a suicidal nuclear first strike attack before the SDI system was deployed, instead come to the bargaining table with the country that did have those resources and, hopefully, agree to a real, sincere disarmament pact that would drastically decrease all forces, both nuclear and conventional. Furthermore, the MAD argument was criticized on the grounds that MAD only covered intentional, full-scale nuclear attacks by a rational, non-suicidal opponent with similar values. It did not take into account limited launches, accidental launches, rogue launches, or launches by non-state entities or covert proxies.

During the Reykjavik talks with Mikhail Gorbachev in 1986, Ronald Reagan addressed Gorbachev's concerns about imbalance by stating that SDI technology could be provided to the entire world – including the Soviet Union – to prevent the imbalance from occurring. Gorbachev answered dismissively. When Reagan prompted technology sharing again, Gorbachev stated "we cannot assume an obligation relative to such a transition", referring to the cost of implementing such a program.

A military officer who was involved in covert operations at the time has told journalist Seymour Hersh that much of the publicity about the program was deliberately false and intended to expose Soviet spies:

For example, the published stories about our Star Wars programme were replete with misinformation and forced the Russians to expose their sleeper agents inside the American government by ordering them to make a desperate attempt to find out what the US was doing. But we could not risk exposure of the administration's role and take the chance of another McCarthy period. So there were no prosecutions. We dried up and eliminated their access and left the spies withering on the vine ... Nobody on the Joint Chiefs of Staff ever believed we were going to build Star Wars, but if we could convince the Russians that we could survive a first strike, we win the game.

Whistleblower

In 1992, scientist Aldric Saucier was given whistleblower protection after he was fired and complained about "wasteful spending on research and development" at the SDI. Saucier also lost his security clearance.