In historical linguistics, grammaticalization (also known as grammatization or grammaticization) is a process of language change by which words representing objects and actions (i.e. nouns and verbs) become grammatical markers (such as affixes or prepositions). Thus it creates new function words from content words, rather than deriving them from existing bound, inflectional constructions. For example, the Old English verb willan 'to want', 'to wish' has become the Modern English auxiliary verb will, which expresses intention or simply futurity. Some concepts are often grammaticalized, while others, such as evidentiality, are not so much.

For an understanding of this process, a distinction needs to be made between lexical items or content words, which carry specific lexical meaning, and grammatical items or function words, which serve mainly to express grammatical relationships between the different words in an utterance. Grammaticalization has been defined as "the change whereby lexical items and constructions come in certain linguistic contexts to serve grammatical functions, and, once grammaticalized, continue to develop new grammatical functions". Where grammaticalization takes place, nouns and verbs which carry certain lexical meaning develop over time into grammatical items such as auxiliaries, case markers, inflections, and sentence connectives.

A well-known example of grammaticalization is that of the process in which the lexical cluster let us, for example in "let us eat", is reduced to let's as in "let's you and me fight". Here, the phrase has lost its lexical meaning of "allow us" and has become an auxiliary introducing a suggestion, the pronoun 'us' reduced first to a suffix and then to an unanalyzed phoneme.

History

The concept was developed in the works of Bopp (1816), Schlegel (1818), Humboldt (1825) and Gabelentz (1891). Humboldt, for instance, came up with the idea of evolutionary language. He suggested that in all languages grammatical structures evolved out of a language stage in which there were only words for concrete objects and ideas. In order to successfully communicate these ideas, grammatical structures slowly came into existence. Grammar slowly developed through four different stages, each in which the grammatical structure would be more developed. Though neo-grammarians like Brugmann rejected the separation of language into distinct "stages" in favour of uniformitarian assumptions, they were positively inclined towards some of these earlier linguists' hypotheses.

The term "grammaticalization" in the modern sense was coined by the French linguist Antoine Meillet in his L'évolution des formes grammaticales (1912). Meillet's definition was "the attribution of grammatical character to an erstwhile autonomous word". Meillet showed that what was at issue was not the origins of grammatical forms but their transformations. He was thus able to present a notion of the creation of grammatical forms as a legitimate study for linguistics. Later studies in the field have further developed and altered Meillet's ideas and have introduced many other examples of grammaticalization.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the field of linguistics was strongly concerned with synchronic studies of language change, with less emphasis on historical approaches such as grammaticalization. It did however, mostly in Indo-European studies, remain an instrument for explaining language change.

It was not until the 1970s, with the growth of interest in discourse analysis and linguistic universals, that the interest for grammaticalization in linguistic studies began to grow again. A greatly influential work in the domain was Christian Lehmann's Thoughts on Grammaticalization (1982). This was the first work to emphasize the continuity of research from the earliest period to the present, and it provided a survey of the major work in the field. Lehmann also invented a set of 'parameters', a method along which grammaticality could be measured both synchronically and diachronically.

Another important work was Heine and Reh's Grammaticalization and Reanalysis in African Languages (1984). This work focussed on African languages synchronically from the point of view of grammaticalization. They saw grammaticalization as an important tool for describing the workings of languages and their universal aspects and it provided an exhaustive list of the pathways of grammaticalization.

The great number of studies on grammaticalization in the last decade (up to 2018) show grammaticalization remains a popular item and is regarded as an important field within linguistic studies in general. Among recent publications there is a wide range of descriptive studies trying to come up with umbrella definitions and exhaustive lists, while others tend to focus more on its nature and significance, questioning the opportunities and boundaries of grammaticalization. An important and popular topic which is still debated is the question of unidirectionality.

Mechanisms

It is difficult to capture the term "grammaticalization" in one clear definition (see the 'various views on grammaticalization' section below). However, there are some processes that are often linked to grammaticalization. These are semantic bleaching, morphological reduction, phonetic erosion, and obligatorification.

Semantic bleaching

Semantic bleaching, or desemanticization, has been seen from early on as a characteristic of grammaticalization. It can be described as the loss of semantic content. More specifically, with reference to grammaticalization, bleaching refers to the loss of all (or most) lexical content of an entity while only its grammatical content is retained, for example James Matisoff described bleaching as "the partial effacement of a morpheme's semantic features, the stripping away of some of its precise content so it can be used in an abstracter, grammatical-hardware-like way". John Haiman wrote that "semantic reduction, or bleaching, occurs as a morpheme loses its intention: From describing a narrow set of ideas, it comes to describe an ever broader range of them, and eventually may lose its meaning altogether". He saw this as one of the two kinds of change that are always associated with grammaticalization (the other being phonetic reduction).

For example, both English suffixes -ly (as in bodily and angrily), and -like (as in catlike or yellow-like) ultimately come from an earlier Proto-Germanic etymon, *līką, which meant body or corpse. There is no salient trace of that original meaning in the present suffixes for the native speaker, but speakers instead treat the more newly-formed suffixes as bits of grammar that help them form new words. One could make the connection between the body or shape of a physical being and the abstract property of likeness or similarity, but only through metonymic reasoning, after one is explicitly made aware of this connection.

Morphological reduction

Once a linguistic expression has changed from a lexical to a grammatical meaning (bleaching), it is likely to lose morphological and syntactic elements that were characteristic of its initial category, but which are not relevant to the grammatical function. This is called decategorialization, or morphological reduction.

For example, the demonstrative 'that' as in "that book" came to be used as a relative clause marker, and lost the grammatical category of number ('that' singular vs. 'those' plural), as in "the book that I know" versus "the things that I know".

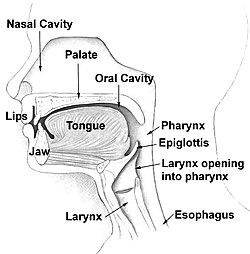

Phonetic erosion

Phonetic erosion (also called phonological attrition or phonological reduction), is another process that is often linked to grammaticalization. It implies that a linguistic expression loses phonetic substance when it has undergone grammaticalization. Heine writes that "once a lexeme is conventionalized as a grammatical marker, it tends to undergo erosion; that is, the phonological substance is likely to be reduced in some way and to become more dependent on surrounding phonetic material".

Bernd Heine and Tania Kuteva have described different kinds of phonetic erosion for applicable cases:

- Loss of phonetic segments, including loss of full syllables.

- Loss of suprasegmental properties, such as stress, tone, or intonation.

- Loss of phonetic autonomy and adaptation to adjacent phonetic units.

- Phonetic simplification

'Going to' → 'gonna' (or even 'I am going to' → 'I'm gonna' → 'I'mma') and 'because' → 'coz' are examples of erosion in English. Some linguists trace erosion to the speaker's tendency to follow the principle of least effort, while others think that erosion is a sign of changes taking place.

However, phonetic erosion, a common process of language change that can take place with no connection to grammaticalization, is not a necessary property of grammaticalization. For example, the Latin construction of the type clarā mente, meaning 'with a clear mind' is the source of modern Romance productive adverb formation, as in Italian chiaramente, and Spanish claramente 'clearly'. In both of those languages, -mente in this usage is interpretable by today's native speakers only as a morpheme signaling 'adverb' and it has undergone no phonological erosion from the Latin source, mente. This example also illustrates that semantic bleaching of a form in its grammaticalized morphemic role does not necessarily imply bleaching of its lexical source, and that the two can separate neatly in spite of maintaining identical phonological form: the noun mente is alive and well today in both Italian and Spanish with its meaning 'mind', yet native speakers do not recognize the noun 'mind' in the suffix -mente.

The phonetic erosion may bring a brand-new look to the phonological system of a language, by changing the inventory of phones and phonemes, making new arrangements in the phonotactic patterns of a syllable, etc. Special treatise on the phonological consequences of grammaticalization and lexicalization in the Chinese languages can be found in Wei-Heng Chen (2011), which provides evidence that a morphophonological change can later change into a purely phonological change, and evidence that there is a typological difference in the phonetic and phonological consequences of grammaticalization between monosyllabic languages (featuring an obligatory match between syllable and morpheme, with exceptions of either loanwords or derivations like reduplicatives or diminutives, other morphological alternations) vs non-monosyllabic languages (including disyllabic or bisyllabic Austronesian languages, Afro-Asiatic languages featuring a tri-consonantal word root, Indo-European languages without a 100% obligatory match between such a sound unit as syllable and such a meaning unit as morpheme or word, despite an assumed majority of monosyllabic reconstructed word stems/roots in the Proto-Indo-European hypothesis), a difference mostly initiated by the German linguist W. Humboldt, putting Sino-Tibetan languages in a sharp contrast to the other languages in the world in typology.

Obligatorification

Obligatorification occurs when the use of linguistic structures becomes increasingly more obligatory in the process of grammaticalization. Lehmann describes it as a reduction in transparadigmatic variability, by which he means that "the freedom of the language user with regard to the paradigm as a whole" is reduced. Examples of obligatoriness can be found in the category of number, which can be obligatory in some languages or in specific contexts, in the development of articles, and in the development of personal pronouns of some languages. Some linguists, like Heine and Kuteva, stress the fact that even though obligatorification can be seen as an important process, it is not necessary for grammaticalization to take place, and it also occurs in other types of language change.

Although these 'parameters of grammaticalization' are often linked to the theory, linguists such as Bybee et al. (1994) have acknowledged that independently, they are not essential to grammaticalization. In addition, most are not limited to grammaticalization but can be applied in the wider context of language change. Critics of the theory of grammaticalization have used these difficulties to claim that grammaticalization has no independent status of its own, that all processes involved can be described separately from the theory of grammaticalization. Janda, for example, wrote that "given that even writers on grammaticalization themselves freely acknowledge the involvement of several distinct processes in the larger set of phenomena, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the notion of grammaticalization, too, tends to represent an epiphenomenal telescoping. That is, it may involve certain typical "path(way)s", but the latter seem to be built out of separate stepping-stones which can often be seen in isolation and whose individual outlines are always distinctly recognizable".

Clines of grammaticality – cycles of categorial downgrading

In the process of grammaticalization, an uninflected lexical word (or content word) is transformed into a grammar word (or function word). The process by which the word leaves its word class and enters another is not sudden, but occurs by a gradual series of individual shifts. The overlapping stages of grammaticalization form a chain, generally called a cline. These shifts generally follow similar patterns in different languages. Linguists do not agree on the precise definition of a cline or on its exact characteristics in given instances. It is believed that the stages on the cline do not always have a fixed position, but vary. However, Hopper and Traugott's famous pattern for the cline of grammaticalization illustrates the various stages of the form:

This particular cline is called "the cline of grammaticality" or the "cycle of categorial downgrading", and it is a common one. In this cline every item to the right represents a more grammatical and less lexical form than the one to its left.

Examples developing a future tense

It is very common for full verbs to become auxiliaries and eventually inflexional endings.

An example of this phenomenon can be seen in the change from the Old English (OE) verb willan ('to want/to wish') to an auxiliary verb signifying intention in Middle English (ME). In Present-Day English (PDE), this form is even shortened to 'll and no longer necessarily implies intention, but often is simply a mark of future tense (see shall and will). The PDE verb 'will' can thus be said to have less lexical meaning than its preceding form in OE.

- Content word: Old English willan (to want/to wish)

- Grammatical word: Middle English and Modern English will, e.g. "I will go to the market"; auxiliary expressing intention, lacking many features of English verbs

such as an inflected past tense, in Modern English usage. The use of

"would" as the past tense of "will", though more common in Middle

English, has become archaic, demonstrating the ongoing loss of lexical

content.

- Modern English will, e.g. "I will see you later"; auxiliary expressing futurity but not necessarily intention (similar in meaning to "I am gonna see you later")

- Clitic: Modern English 'll, e.g. "My friends'll be there this evening." This clitic form phonologically adapts to its surroundings and cannot receive stress unlike the uncontracted form.

- Inflectional suffix: This has not occurred in English, but hypothetically, will could become further grammaticalized to the point that it forms an inflexional affix indicating future tense, e.g. "I needill your help." in the place of "I will need your help." or "I'll need your help."

The final stage of grammaticalization has happened in many languages. For example, in Serbo-Croatian, the Old Church Slavonic verb xъtěti ("to want/to wish") has gone from a content word (hoće hoditi "s/he wants to walk") to an auxiliary verb in phonetically reduced form (on/ona će hoditi "s/he will walk") to a clitic (hoditi će), and finally to a fused inflection (hodiće "s/he will walk").

Compare the German verb wollen which has partially undergone a similar path of grammaticalization, and note the simultaneous existence of the non-grammaticalized Modern English verb to will (e.g. "He willed himself to continue along the steep path.") or hoteti in Serbo-Croatian (Hoċu da hodim = I want that I walk).

In Latin the original future tense forms (e.g. cantabo) were dropped when they became phonetically too close to the imperfect forms (cantabam). Instead, a phrase like cantare habeo, literally 'I have got to sing' acquired the sense of futurity (cf. I have to sing). Finally it became true future tense in almost all Romance languages and the auxiliary became a full-fledged inflection (cf. Spanish cantaré, cantarás, cantará, French je chanterai, tu chanteras, il/elle chantera, Italian canterò, canterai, canterà, 'I will sing', 'you will sing', 's/he will sing'). In some verbs the process went further and produced irregular forms [cf. Spanish haré (instead of *haceré, 'I'll do') and tendré (not *teneré, 'I'll have', the loss of e followed by epenthesis of d is especially common)] and even regular forms (the change of the a in the stem cantare to e in canterò has affected the whole class of conjugation type I Italian verbs).

Japanese compound verbs

An illustrative example of this cline is in the orthography of Japanese compound verbs. Many Japanese words are formed by connecting two verbs, as in 'go and ask (listen)' (行って聞く, ittekiku), and in Japanese orthography lexical items are generally written with kanji (here 行く and 聞く), while grammatical items are written with hiragana (as in the connecting て). Compound verbs are thus generally written with a kanji for each constituent verb, but some suffixes have become grammaticalized, and are written in hiragana, such as 'try out, see' (〜みる, -miru), from 'see' (見る, miru), as in 'try eating (it) and see' (食べてみる, tabetemiru).

Historical linguistics

In Grammaticalization (2003) Hopper and Traugott state that the cline of grammaticalization has both diachronic and synchronic implications. Diachronically (i.e. looking at changes over time), clines represent a natural path along which forms or words change over time. However, synchronically (i.e. looking at a single point in time), clines can be seen as an arrangement of forms along imaginary lines, with at one end a 'fuller' or lexical form and at the other a more 'reduced' or grammatical form. What Hopper and Traugott mean is that from a diachronic or historical point of view, changes of word forms is seen as a natural process, whereas synchronically, this process can be seen as inevitable instead of historical.

The studying and documentation of recurrent clines enable linguists to form general laws of grammaticalization and language change in general. It plays an important role in the reconstruction of older states of a language. Moreover, the documenting of changes can help to reveal the lines along which a language is likely to develop in the future.

Unidirectionality hypothesis

The unidirectionality hypothesis is the idea that grammaticalization, the development of lexical elements into grammatical ones, or less grammatical into more grammatical, is the preferred direction of linguistic change and that a grammatical item is much less likely to move backwards rather than forwards on Hopper & Traugott's cline of grammaticalization.

In the words of Bernd Heine, "grammaticalization is a unidirectional process, that is, it leads from less grammatical to more grammatical forms and constructions". That is one of the strongest claims about grammaticalization, and is often cited as one of its basic principles. In addition, unidirectionality refers to a general developmental orientation which all (or the large majority) of the cases of grammaticalization have in common, and which can be paraphrased in abstract, general terms, independent of any specific case.

The idea of unidirectionality is an important one when trying to predict language change through grammaticalization (and for making the claim that grammaticalization can be predicted). Lessau notes that "unidirectionality in itself is a predictive assertion in that it selects the general type of possible development (it predicts the direction of any given incipient case)," and unidirectionality also rules out an entire range of development types that do not follow this principle, hereby limiting the amount of possible paths of development.

Counterexamples (degrammaticalization)

Although unidirectionality is a key element of grammaticalization, exceptions exist. Indeed, the possibility of counterexamples, coupled with their rarity, is given as evidence for the general operating principle of unidirectionality. According to Lyle Campbell, however, advocates often minimize the counterexamples or redefine them as not being part of the grammaticalization cline. He gives the example of Hopper and Traugott (1993), who treat some putative counterexamples as cases of lexicalization in which a grammatical form is incorporated into a lexical item but does not itself become a lexical item. An example is the phrase to up the ante, which incorporates the preposition up (a function word) in a verb (a content word) but without up becoming a verb outside of this lexical item. Since it is the entire phrase to up the ante that is the verb, Hopper and Traugott argue that the word up itself cannot be said to have degrammaticalized, a view that is challenged to some extent by parallel usages such as to up the bid, to up the payment, to up the deductions, to up the medication, by the fact that in all cases the can be replaced by a possessive (my, your, her, Bill's, etc.), and by further extensions still: he upped his game 'he improved his performance'.

Examples that are not confined to a specific lexical item are less common. One is the English genitive -'s, which, in Old English, was a suffix but, in Modern English, is a clitic. As Jespersen (1894) put it,

In Modern English...(compared to OE) the -s is much more independent: it can be separated from its main word by an adverb such as else (somebody else's hat ), by a prepositional clause such as of England (the queen of England's power ), or even by a relative clause such as I saw yesterday (the man I saw yesterday's car)...the English genitive is in fact no longer a flexional form...historically attested facts show us in the most unequivocal way a development - not, indeed, from an originally self-existent word to a mere flexional ending, but the exactly opposite development of what was an inseparable part of a complicated flexional system to greater and greater emancipation and independence.

Traugott cites a counterexample from function to content word proposed by Kate Burridge (1998): the development in Pennsylvania German of the auxiliary wotte of the preterite subjunctive modal welle 'would' (from 'wanted') into a full verb 'to wish, to desire'.

In comparison to various instances of grammaticalization, there are relatively few counterexamples to the unidirectionality hypothesis, and they often seem to require special circumstances to occur. One is found in the development of Irish Gaelic with the origin of the first-person-plural pronoun muid (a function word) from the inflectional suffix -mid (as in táimid 'we are') because of a reanalysis based on the verb-pronoun order of the other persons of the verb. Another well-known example is the degrammaticalization of the North Saami abessive ('without') case suffix -haga to the postposition haga 'without' and further to a preposition and a free-standing adverb. Moreover, the morphologically analogous derivational suffix -naga 'stained with' (e.g., gáffenaga 'stained with coffee', oljonaga 'stained with oil') – itself based on the essive case marker *-na – has degrammaticalized into an independent noun naga 'stain'.

Views on grammaticalization

Linguists have come up with different interpretation of the term 'grammaticalization', and there are many alternatives to the definition given in the introduction. The following will be a non-exhaustive list of authors who have written about the subject with their individual approaches to the nature of the term 'grammaticalization'.

- Antoine Meillet (1912): "Tandis que l'analogie peut renouveler le détail des formes, mais laisse le plus souvent intact le plan d'ensemble du système grammatical, la 'grammaticalisation' de certains mots crée des formes neuves, introduit des catégories qui n'avaient pas d'expression linguistique, transforme l'ensemble du système." ("While the analogy can renew the detail of the forms, but often leaves untouched the overall plan of the grammatical system, the 'grammaticalization' of certain words creates new forms, introduces categories for which there was no linguistical expression, and transforms the whole of the system.")

- Jerzy Kurylowicz (1965): His "classical" definition is probably the one most often referred to: "Grammaticalization consists in the increase of the range of a morpheme advancing from a lexical to a grammatical or from a less grammatical to a more grammatical status, e.g. from a derivative formant to an inflectional one".

Since then, the study of grammaticalization has become broader, and linguists have extended the term into various directions.

- Christian Lehmann (1982): Writer of Thoughts on Grammaticalization and New Reflections on Grammaticalization and Lexicalization, wrote that "Grammaticalization is a process leading from lexemes to grammatical formatives. A number of semantic, syntactic and phonological processes interact in the grammaticalization of morphemes and of whole constructions. A sign is grammaticalized to the extent that it is devoid of concrete lexical meaning and takes part in obligatory grammatical rules".

- Paul Hopper (1991): Hopper defined the five 'principles' by which you can detect grammaticalization while it is taking place: "layering", the development of additional expressions for a function; "divergence" (also called "split" by other theorists), in which a form develops a grammatical sense in addition to its lexical sense; "specialization", reducing the scope of lexical meaning until only grammatical function remains; "persistence", traces of lexical meaning in a grammaticalized form; and "de-categorialization", the loss of a form's morphosyntactic properties.

- František Lichtenberk (1991): In his article on "The Gradualness of Grammaticalization", he defined grammaticalization as "a historical process, a kind of change that has certain consequences for the morphosyntactic categories of a language and thus for the grammar of the language.

- James A. Matisoff (1991): Matisoff used the term 'metaphor' to describe grammaticalization when he wrote: "Grammatization may also be viewed as a subtype of metaphor (etymologically "carrying beyond"), our most general term for a meaning shift. [...] Grammaticalization is a metaphorical shift toward the abstract, "metaphor" being defined as an originally conscious or voluntary shift in a word's meaning because of some perceived similarity.

- Elizabeth Traugott & Bernd Heine (1991): Together, they edited a two-volume collection of papers from a 1988 conference organized by Talmy Givón under the title Approaches to Grammaticaliztion. They defined grammaticalization as "a linguistic process, both through time and synchronically, of organization of categories and of coding. The study of grammaticalization therefore highlights the tension between relatively unconstrained lexical expression and more constrained morphosyntactic coding, and points to relative indeterminacy in language and to the basic non-discreteness of categories".

- Olga Fischer & Anette Rosenbach (2000): In the introduction of their book Pathways of Change, a summary is given of recent approaches to grammaticalization. "The term 'grammaticalization' is today used in various ways. In a fairly loose sense, 'grammaticalized' often simply refers to the fact that a form or construction has become fixed and obligatory. (...) In a stricter sense, however, (...) the notion of 'grammaticalization' is first and foremost a diachronic process with certain typical mechanisms."

- Lyle Campbell lists proposed counterexamples in his article "What's wrong with grammaticalization?". In the same issue of Language Sciences, Richard D. Janda cites over 70 works critical of the unidirectionality hypothesis in his article "Beyond 'pathways' and 'unidirectionality'".

- The first monograph on degrammaticalization and its relation to grammaticalization was published in 2009 by Muriel Norde.