| |

| Founded | July 1961 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Founder | Peter Benenson |

| Type | Nonprofit INGO |

| Headquarters | London, WC1 United Kingdom |

| Location |

|

| Services | Protecting human rights |

| Fields | Legal advocacy, Media attention, direct-appeal campaigns, research, lobbying |

Members

| More than seven million members and supporters |

| Kumi Naidoo | |

| Website | amnesty.org |

Amnesty International (commonly known as Amnesty or AI) is a London-based non-governmental organization focused on human rights. The organization says it has more than seven million members and supporters around the world.

The stated mission of the organization is to campaign for "a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments."

Amnesty International was founded in London in 1961, following the publication of the article "The Forgotten Prisoners" in The Observer on 28 May 1961, by the lawyer Peter Benenson. Amnesty draws attention to human rights abuses and campaigns for compliance with international laws and standards. It works to mobilize public opinion to generate pressure on governments that let abuse take place. Amnesty considers capital punishment to be "the ultimate, irreversible denial of human rights." The organization was awarded the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize for its "defence of human dignity against torture," and the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights in 1978.

In the field of international human rights organizations, Amnesty has the third longest history, after the International Federation for Human Rights, and broadest name recognition, and is believed by many to set standards for the movement as a whole.

History

1960s

Peter Benenson, the founder of Amnesty International. He worked for Britain's GC&CS at Bletchley Park during World War II.

Amnesty International was founded in London in July 1961 by English labour lawyer Peter Benenson along with Professor of Law and friend Philip James. According to Benenson's own account, he was travelling on the London Underground on 19 November 1960 when he read that two Portuguese students from Coimbra had been sentenced to seven years of imprisonment in Portugal for allegedly "having drunk a toast to liberty". Researchers have never traced the alleged newspaper article in question. In 1960, Portugal was ruled by the Estado Novo government of António de Oliveira Salazar. The government was authoritarian in nature and strongly anti-communist,

suppressing enemies of the state as anti-Portuguese. In his significant

newspaper article "The Forgotten Prisoners", Benenson later described

his reaction as follows:

Open your newspaper any day of the week and you will find a story from somewhere of someone being imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government... The newspaper reader feels a sickening sense of impotence. Yet if these feelings of disgust could be united into common action, something effective could be done.

Benenson worked with friend Eric Baker. Baker was a member of the Religious Society of Friends who had been involved in funding the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament as well as becoming head of Quaker Peace and Social Witness, and in his memoirs Benenson described him as "a partner in the launching of the project". In consultation with other writers, academics and lawyers and, in particular, Alec Digges, they wrote via Louis Blom-Cooper to David Astor, editor of The Observer

newspaper, who, on 28 May 1961, published Benenson's article "The

Forgotten Prisoners". The article brought the reader's attention to

those "imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion

are unacceptable to his government" or, put another way, to violations, by governments, of articles 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(UDHR). The article described these violations occurring, on a global

scale, in the context of restrictions to press freedom, to political

oppositions, to timely public trial

before impartial courts, and to asylum. It marked the launch of "Appeal

for Amnesty, 1961", the aim of which was to mobilize public opinion,

quickly and widely, in defence of these individuals, whom Benenson named

"Prisoners of Conscience". The "Appeal for Amnesty" was reprinted by a

large number of international newspapers. In the same year, Benenson had

a book published, Persecution 1961, which detailed the cases of nine prisoners of conscience investigated and compiled by Benenson and Baker (Maurice Adin, Ashton Jones, Agostinho Neto, Patrick Duncan, Olga Ivinskaya, Luis Taruc, Constantin Noica, Antonio Amat and Hu Feng).

In July 1961 the leadership had decided that the appeal would form the

basis of a permanent organization, Amnesty, with the first meeting

taking place in London. Benenson ensured that all three major political

parties were represented, enlisting members of parliament from the Labour Party, the Conservative Party, and the Liberal Party.

On 30 September 1962, it was officially named "Amnesty International".

Between the "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961" and September 1962 the

organization had been known simply as "Amnesty".

What started as a short appeal soon became a permanent

international movement working to protect those imprisoned for

non-violent expression of their views and to secure worldwide

recognition of Articles 18 and 19 of the UDHR. From the very beginning,

research and campaigning were present in Amnesty International's work. A

library was established for information about prisoners of conscience

and a network of local groups, called "THREES" groups, was started.

Each group worked on behalf of three prisoners, one from each of the

then three main ideological regions of the world: communist, capitalist, and developing.

By the mid-1960s Amnesty International's global presence was

growing and an International Secretariat and International Executive

Committee were established to manage Amnesty International's national

organizations, called "Sections", which had appeared in several

countries. The international movement was starting to agree on its core

principles and techniques. For example, the issue of whether or not to

adopt prisoners who had advocated violence, like Nelson Mandela,

brought unanimous agreement that it could not give the name of

"Prisoner of Conscience" to such prisoners. Aside from the work of the

library and groups, Amnesty International's activities were expanding to

helping prisoners' families, sending observers to trials, making

representations to governments, and finding asylum or overseas

employment for prisoners. Its activity and influence were also

increasing within intergovernmental organizations; it would be awarded

consultative status by the United Nations, the Council of Europe and UNESCO before the decade ended.

In 1967, Peter Benenson resigned after an independent inquiry did

not support his claims that AI had been infiltrated by British agents. Later he claimed that the Central Intelligence Agency had become involved in Amnesty.

1970s

During the 1970s, Seán MacBride and Martin Ennals

led Amnesty International. While continuing to work for prisoners of

conscience, Amnesty International's purview widened to include "fair trial" and opposition to long detention without trial

(UDHR Article 9), and especially to the torture of prisoners (UDHR

Article 5). Amnesty International believed that the reasons underlying

torture of prisoners by governments, were either to acquire and obtain

information or to quell opposition by the use of terror, or both. Also

of concern was the export of more sophisticated torture methods,

equipment and teaching by the superpowers to "client states", for

example by the United States through some activities of the CIA.

Amnesty International drew together reports from countries where

torture allegations seemed most persistent and organized an

international conference on torture. It sought to influence public

opinion to put pressure on national governments by organizing a campaign

for the "Abolition of Torture", which ran for several years.

Amnesty International's membership increased from 15,000 in 1969 to 200,000 by 1979. This growth in resources enabled an expansion of its program, "outside of the prison walls", to include work on "disappearances",

the death penalty and the rights of refugees. A new technique, the

"Urgent Action", aimed at mobilizing the membership into action rapidly

was pioneered. The first was issued on 19 March 1973, on behalf of Luiz

Basilio Rossi, a Brazilian academic, arrested for political reasons.

At the intergovernmental level Amnesty International pressed for application of the UN's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners and of existing humanitarian conventions; to secure ratifications of the two UN Covenants on Human Rights

in 1976; and was instrumental in obtaining additional instruments and

provisions forbidding the practice of maltreatment. Consultative status

was granted at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1972.

In 1976, Amnesty's British Section started a series of fund-raising events that came to be known as The Secret Policeman's Balls series. They were staged in London initially as comedy galas featuring what the Daily Telegraph called "the crème de la crème of the British comedy world" including members of comedy troupe Monty Python, and later expanded to also include performances by leading rock musicians. The series was created and developed by Monty Python alumnus John Cleese and entertainment industry executive Martin Lewis working closely with Amnesty staff members Peter Luff

(Assistant Director of Amnesty 1974–78) and subsequently with Peter

Walker (Amnesty Fund-Raising Officer 1978–82). Cleese, Lewis and Luff

worked together on the first two shows (1976 and 1977). Cleese, Lewis

and Walker worked together on the 1979 and 1981 shows, the first to

carry what the Daily Telegraph described as the "rather brilliantly re-christened" Secret Policeman's Ball title.

The organization was awarded the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize for its "defence of human dignity against torture" and the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights in 1978.

1980s

By 1980 Amnesty International was drawing more criticism from governments. The USSR alleged that Amnesty International conducted espionage, the Moroccan government denounced it as a defender of lawbreakers, and the Argentinian government banned Amnesty International's 1983 annual report.

Throughout the 1980s, Amnesty International continued to campaign

against torture, and on behalf of prisoners of conscience. New issues

emerged, including extrajudicial killings, military, security and police transfers, political killings, and disappearances.

Towards the end of the decade, the growing number of refugees

worldwide became a focus for Amnesty International's. While many of the

world's refugees of the time had been displaced by war and famine,

in adherence to its mandate, Amnesty International concentrated on

those forced to flee because of the human rights violations it was

seeking to prevent. It argued that rather than focusing on new

restrictions on entry for asylum-seekers, governments were to address

the human rights violations which were forcing people into exile.

Apart from a second campaign on torture during the first half of

the decade, two major musical events took place to increase awareness of

Amnesty and of human rights (particularly among younger generations)

during the mid- to late-1980s. The 1986 Conspiracy of Hope

tour, which played five concerts in the US, and culminated in a daylong

show, featuring some thirty-odd acts at Giants Stadium, and the 1988 Human Rights Now! world tour. Human Rights Now!, which was timed to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(UDHR), played a series of concerts on five continents over six weeks.

Both tours featured some of the most famous musicians and bands of the

day.

1990s

Throughout the 1990s, Amnesty continued to grow, to a membership of over seven million in over 150 countries and territories, led by Senegalese Secretary General Pierre Sané.

Amnesty continued to work on a wide range of issues and world events.

For example, South African groups joined in 1992 and hosted a visit by

Pierre Sané to meet with the apartheid government to press for an investigation into allegations of police abuse, an end to arms sales to the African Great Lakes

region and the abolition of the death penalty. In particular, Amnesty

International brought attention to violations committed on specific

groups, including refugees, racial/ethnic/religious minorities, women and those executed or on Death Row. The death penalty report When the State Kills and the "Human Rights are Women's Rights" campaign were key actions for the latter two issues.

During the 1990s, Amnesty International was forced to react to

human rights violations occurring in the context of a proliferation of

armed conflict in Angola, East Timor, the Persian Gulf, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia.

Amnesty International took no position on whether to support or oppose

external military interventions in these armed conflicts. It did not

reject the use of force, even lethal force, or ask those engaged to lay

down their arms. Instead, it questioned the motives behind external

intervention and selectivity of international action in relation to the

strategic interests of those who sent troops. It argued that action

should be taken to prevent human-rights problems from becoming

human-rights catastrophes, and that both intervention and inaction

represented a failure of the international community.

In 1990, when the United States government was deciding whether or not to invade Iraq, a Kuwaiti woman, known to Congress by her first name only, Nayirah, told the congress that when Iraq invaded Kuwait,

she stayed behind after some of her family left the country. She said

she was volunteering in a local hospital when Iraqi soldiers stole the incubators

with children in them and left them to freeze to death. Amnesty

International, who had human rights investigators in Kuwait, confirmed

the story and helped spread it. The organization also inflated the

number of children who were killed by the robbery to over 300, more than

the number of incubators available in the city hospitals of the

country. It was often cited by people, including the Congresspeople who voted to approve the Gulf War,

as one of the reasons to fight. After the war, it was found that the

woman was lying, the story was made up, and her last name was not given,

because her father was a delegate for Kuwait's government at the same

congressional hearing.

In 1995, when AI wanted to promote how Shell Oil Company was involved with the execution of an environmental and human-rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa

in Nigeria, it was stopped. Newspapers and advertising companies

refused to run AI's ads because Shell Oil was a customer of theirs as

well. Shell's main argument was that it was drilling oil in a country

that already violated human rights and had no way to enforce

human-rights policies. To combat the buzz that AI was trying to create,

it immediately publicized how Shell was helping to improve overall life

in Nigeria. Salil Shetty, the director of Amnesty, said, "Social media

re-energises the idea of the global citizen".

James M. Russell notes how the drive for profit from private media

sources conflicts with the stories that AI wants to be heard.

Amnesty International was proactive in pushing for recognition of

the universality of human rights. The campaign 'Get Up, Sign Up' marked

50 years of the UDHR. Thirteen million pledges were collected in

support, and the Decl music concert was held in Paris on 10 December

1998 (Human Rights Day). At the intergovernmental level, Amnesty International argued in favour of creating a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (established 1993) and an International Criminal Court (established 2002).

After his arrest in London in 1998 by the Metropolitan Police, Amnesty International became involved in the legal battle of Senator Augusto Pinochet, former Chilean dictator, who sought to avoid extradition to Spain to face charges. Lord Hoffman

had an indirect connection with Amnesty International, and this led to

an important test for the appearance of bias in legal proceedings in UK

law. There was a suit against the decision to release Senator Pinochet, taken by the then British Home Secretary

Mr Jack Straw, before that decision had actually been taken, in an

attempt to prevent the release of Senator Pinochet. The English High Court refused the application, and Senator Pinochet was released and returned to Chile.

2000s

After 2000, Amnesty International's primary focus turned to the challenges arising from globalization and the reaction to the 11 September 2001 attacks

in the United States. The issue of globalization provoked a major shift

in Amnesty International policy, as the scope of its work was widened

to include economic, social and cultural rights, an area that it had

declined to work on in the past. Amnesty International felt this shift

was important, not just to give credence to its principle of the

indivisibility of rights, but because of what it saw as the growing

power of companies and the undermining of many nation states as a result

of globalization.

In the aftermath of 11 September attacks, the new Amnesty International Secretary General, Irene Khan,

reported that a senior government official had said to Amnesty

International delegates: "Your role collapsed with the collapse of the

Twin Towers in New York." In the years following the attacks, some believe that the gains made by human rights organizations over previous decades had possibly been eroded.

Amnesty International argued that human rights were the basis for the

security of all, not a barrier to it. Criticism came directly from the Bush administration and The Washington Post, when Khan, in 2005, likened the US government's detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to a Soviet Gulag.

During the first half of the new decade, Amnesty International turned its attention to violence against women, controls on the world arms trade, concerns surrounding the effectiveness of the UN, and ending torture. With its membership close to two million by 2005, Amnesty continued to work for prisoners of conscience.

In 2007, AI's executive committee decided to support access to

abortion "within reasonable gestational limits...for women in cases of

rape, incest or violence, or where the pregnancy jeopardizes a mother's

life or health".

Amnesty International reported, concerning the Iraq War,

on 17 March 2008, that despite claims the security situation in Iraq

has improved in recent months, the human rights situation is disastrous,

after the start of the war five years earlier in 2003.

In 2009, Amnesty International accused Israel and the Palestinian

Hamas movement of committing war crimes during Israel's January

offensive in Gaza, called Operation Cast Lead, that resulted in the deaths of more than 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis.

The 117-page Amnesty report charged Israeli forces with killing

hundreds of civilians and wanton destruction of thousands of homes.

Amnesty found evidence of Israeli soldiers using Palestinian civilians

as human shields. A subsequent United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict

was carried out; Amnesty stated that its findings were consistent with

those of Amnesty's own field investigation, and called on the UN to act

promptly to implement the mission's recommendations.

2010s

Amnesty International, 19 March 2011.

Japanese branch of Amnesty International, 23 May 2014.

Amnesty International sign in Newcastle upon Tyne, 18 July 2015.

2010

In February 2010, Amnesty suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticized Amnesty for its links with Moazzam Begg, director of Cageprisoners. She said it was "a gross error of judgment" to work with "Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban".

Amnesty responded that Sahgal was not suspended "for raising these

issues internally... [Begg] speaks about his own views ..., not Amnesty

International's". Among those who spoke up for Saghal were Salman Rushdie, Member of Parliament Denis MacShane, Joan Smith, Christopher Hitchens, Martin Bright, Melanie Phillips, and Nick Cohen.

2011

In February 2011, Amnesty requested that Swiss authorities start a criminal investigation of former US President George W. Bush and arrest him.

In July 2011, Amnesty International celebrated its 50 years with an animated short film directed by Carlos Lascano, produced by Eallin Motion Art and Dreamlife Studio, with music by Academy Award-winner Hans Zimmer and nominee Lorne Balfe. The film shows that the fight for humanity is not yet over.

2012

In August

2012, Amnesty International's chief executive in India sought an

impartial investigation, led by the United Nations, to render justice to

those affected by war crimes in Sri Lanka.

2014

On 18 August 2014, in the wake of demonstrations sparked by people protesting the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown,

an unarmed 18-year-old man, and subsequent acquittal of Darren Wilson,

the officer who shot him, Amnesty International sent a 13-person

contingent of human rights activists to seek meetings with officials as

well as to train local activists in non-violent protest methods. This was the first time that the organization has deployed such a team to the United States. In a press release, AI USA director Steven W. Hawkins

said, "The U.S. cannot continue to allow those obligated and duty-bound

to protect to become those who their community fears most."

2016

In February

2016, Amnesty International launched its annual report of human rights

around the world titled "The State of the World's Human Rights". It

warns from the consequences of "us vs them" speech which divided human

beings into two camps. It states that this speech enhances a global

pushback against human rights and makes the world more divided and more

dangerous. It also states that in 2016, governments turned a blind eye

to war crimes and passed laws that violate free expression. Donald Trump signed an executive order in an attempt to prevent refugees from seeking resettlement in the United States. Elsewhere, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Thailand and Turkey

carried out massive crackdowns, while authorities in other countries

continued to implement security measures represent an infringement on

rights. In June 2016, Amnesty International has called on the United Nations General Assembly to "immediately suspend" Saudi Arabia from the UN Human Rights Council.

Richard Bennett, head of Amnesty's UN Office, said: "The credibility of

the U.N. Human Rights Council is at stake. Since joining the council,

Saudi Arabia's dire human rights record at home has continued to

deteriorate and the coalition it leads has unlawfully killed and injured

thousands of civilians in the conflict in Yemen."

In December 2016, Amnesty International revealed that Voiceless Victims, a fake non-profit organization which claims to raise awareness for migrant workers who are victims of human rights abuses in Qatar, had been trying to spy on their staff.

2017

Amnesty International published its annual report for the year 2016–2017 on 21 February 2017. Secretary General Salil Shetty's

opening statement in the report highlighted many ongoing international

abuses as well as emerging threats. Shetty drew attention, among many

issues, to the Syrian Civil War, the use of chemical weapons in the War in Darfur, outgoing United States President Barack Obama's expansion of drone warfare, and the successful 2016 presidential election campaign of Obama's successor Donald Trump.

Shetty stated that the Trump election campaign was characterized by

"poisonous" discourse in which "he frequently made deeply divisive

statements marked by misogyny and xenophobia, and pledged to roll back

established civil liberties and introduce policies which would be

profoundly inimical to human rights." In his opening summary, Shetty

stated that "the world in 2016 became a darker and more unstable place."

In July 2017, Turkish police detained 10 human rights activists during a workshop on digital security at a hotel near Istanbul. Eight people, including Idil Eser, Amnesty International director in Turkey, as well as German Peter Steudtner

and Swede Ali Gharavi, were arrested. Two others were detained but

released pending trial. They were accused of aiding armed terror

organizations in alleged communications with suspects linked to Kurdish and left-wing militants, as well as the movement led by US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen.

2018

Amnesty International published its 2017/2018 report in February 2018.

In October 2018, an Amnesty International researcher was abducted

and beaten while observing demonstrations in Magas, the capital of

Ingushetia, Russia.

On 25 October, federal officers raided the Bengaluru

office for 10 hours on a suspicion that the organization had violated

foreign direct investment guidelines on the orders of the Enforcement Directorate. Employees and supporters of Amnesty International say this is an act to intimidate organizations

and people who question the authority and capabilities of government

leaders. Aakar Patel, the Executive Director of the Indian branch

claimed, "The Enforcement Directorate’s raid on our office today shows

how the authorities are now treating human rights organizations like criminal enterprises, using heavy-handed methods. The current Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, has been criticized for harming civil society in India, specifically by targeting advocacy groups. Modi has cancelled the registration of about 15,000 nongovernmental organizations under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA); the U.N. has issued statemenets against the policies that allow these cancellations to occur. Though nothing was found to confirm these accusations, the government plans on continuing the investigation and has frozen the bank accounts of all the offices in India. A spokesperson for the Enforcement Directorate has said the investigation could take three months to complete.

On 30 October 2018, Amnesty called for the arrest and prosecution

of Nigerian security forces claiming that they used excessive force

against Shi’a protesters during a peaceful religious procession around

Abuja, Nigeria. At least 45 were killed and 122 were injured during the

event .

In November 2018, Amnesty reported the arrest of 19 or more

rights activists and lawyers in Egypt. The arrests were made by the

Egyptian authorities as part of the regime's ongoing crackdown on

dissent. One of the arrested was Hoda Abdel-Monaim, a 60-year-old human

rights lawyer and former member of the National Council for Human

Rights. Amnesty reported that following the arrests Egyptian

Coordination for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) decided to suspend its

activities due to the hostile environment towards civil society in the

country.

On 5 December 2018, Amnesty International strongly condemned the execution of Ihar Hershankou and Siamion Berazhnoy in Belarus. They were shot despite UN Human Rights Committee request for a delay.

2019

In February 2019, Amnesty International 's management team offered to resign after an independent report found what it called a "toxic culture" of workplace bullying, and found evidence of bullying, harassment, sexism and racism, after being asked to investigate the suicides of 30-year Amnesty veteran Gaetan Mootoo in Paris in May 2018 (who left a note citing work pressures), and 28-year-old intern Rosalind McGregor in Geneva in July 2018.

In April 2019, Amnesty International's deputy director for

research in Europe, Massimo Moratti, warned that if extradited to the

United States, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange

would face the "risk of serious human rights violations, namely

detention conditions, which could violate the prohibition of torture".

Structure

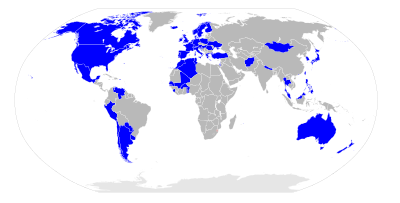

Amnesty International Sections, 2012

The Amnesty Canadian headquarters in Ottawa.

Amnesty International is largely made up of voluntary members, but

retains a small number of paid professionals. In countries in which

Amnesty International has a strong presence, members are organized as

"sections". Sections co-ordinate basic Amnesty International activities

normally with a significant number of members, some of whom will form

into "groups", and a professional staff. Each have a board of directors.

In 2005 there were 52 sections worldwide. "Structures" are aspiring

sections. They also co-ordinate basic activities but have a smaller

membership and a limited staff. In countries where no section or

structure exists, people can become "international members". Two other

organizational models exist: "international networks", which promote

specific themes or have a specific identity, and "affiliated groups",

which do the same work as section groups, but in isolation.

The organizations outlined above are represented by the

International Council (IC) which is led by the IC Chairperson. Members

of sections and structures have the right to appoint one or more

representatives to the Council according to the size of their

membership. The IC may invite representatives from International

Networks and other individuals to meetings, but only representatives

from sections and structures have voting rights. The function of the IC

is to appoint and hold accountable internal governing bodies and to

determine the direction of the movement. The IC convenes every two

years.

The International Board (formerly known as the International

Executive Committee [IEC]), led by the International Board Chairperson,

consists of eight members and the International Treasurer. It is elected

by, and accountable to, the IC, and meets at least two times during any

one year and in practice meets at least four times a year. The role of

the International Board is to take decisions on behalf of Amnesty

International, implement the strategy laid out by the IC, and ensure

compliance with the organization's statutes.

The International Secretariat (IS) is responsible for the conduct

and daily affairs of Amnesty International under direction from the

International Board.

It is run by approximately 500 professional staff members and is headed

by a Secretary General. The Secretariat operates several work

programmes; International Law and Organizations; Research; Campaigns;

Mobilization; and Communications. Its offices have been located in

London since its establishment in the mid-1960s.

- Amnesty International Sections, 2005

Algeria; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium (Dutch-speaking); Belgium (French-speaking); Benin; Bermuda; Canada (English-speaking); Canada (French-speaking); Chile; Côte d'Ivoire; Denmark; Faroe Islands; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Guyana; Hong Kong; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Korea (Republic of); Luxembourg; Mauritius; Mexico; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Portugal; Puerto Rico; Senegal; Sierra Leone; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Taiwan; Togo; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States of America; Uruguay; Venezuela - Amnesty International Structures, 2005

Belarus; Bolivia; Burkina Faso; Croatia; Curaçao; Czech Republic; Gambia; Hungary; Malaysia; Mali; Moldova; Mongolia; Pakistan; Paraguay; Slovakia; South Africa; Thailand; Turkey; Ukraine; Zambia; Zimbabwe - International Board (formerly known as "IEC") Chairpersons

Seán MacBride, 1965–74; Dirk Börner, 1974–17; Thomas Hammarberg, 1977–79; José Zalaquett, 1979–82; Suriya Wickremasinghe, 1982–85; Wolfgang Heinz, 1985–96; Franca Sciuto, 1986–89; Peter Duffy, 1989–91; Annette Fischer, 1991–92; Ross Daniels, 1993–19; Susan Waltz, 1996–98; Mahmoud Ben Romdhane, 1999–2000; Colm O Cuanachain, 2001–02; Paul Hoffman, 2003–04; Jaap Jacobson, 2005; Hanna Roberts, 2005–06; Lilian Gonçalves-Ho Kang You, 2006–07; Peter Pack, 2007–11; Pietro Antonioli, 2011–13; and Nicole Bieske, 2013–present. - Secretaries General

| Secretary General | Office | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| 1961–66 | Britain | |

| 1966–68 | Britain | |

| 1968–80 | Britain | |

| 1980–86 | Sweden | |

| 1986–92 | Britain | |

| 1992–2001 | Senegal | |

| 2001–10 | Bangladesh | |

| 2010 – 2018 | India | |

| 2018–present | South Africa |

National sections

| Country/Territory | Local website |

|---|---|

| Amnesty International Algeria | "amnestyalgerie.org". |

| Amnesty International Ghana | "amnestyghana.org". |

| Amnesty International Argentina | "amnistia.org.ar". |

| Amnesty International Australia | "amnesty.org.au". |

| Amnesty International Austria | "amnesty.at". |

| (Amnesty International Belgium) Amnesty International Flanders Amnesty International Francophone Belgium |

"aivl.be". "amnestyinternational.be". |

| Amnesty International Benin | "aibenin.org". |

| Amnesty International Bermuda | "amnestybermuda.org". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2013. |

| Amnesty International Brazil | "anistia.org.br". |

| Amnesty International Burkina Faso | "amnestyburkina.org". |

| Amnesty International Canada (English) Amnistie internationale Canada (Francophone) |

"amnesty.ca". "amnistie.ca". |

| Amnesty International Chile | "amnistia.cl". |

| Amnesty International Czech Republic | "amnesty.cz". |

| Amnesty International Denmark | "amnesty.dk". |

| Amnesty International Faroe Islands | "amnesty.fo". |

| Amnesty International Finland | "amnesty.fi". |

| Amnesty International France | "amnesty.fr". |

| Amnesty International Germany | "amnesty.de". |

| Amnesty International Greece | "amnesty.org.gr". |

| Amnesty International Hong Kong | "amnesty.org.hk". |

| Amnesty International Hungary | "amnesty.hu". |

| Amnesty International Iceland | "amnesty.is". |

| Amnesty International India | "amnesty.org.in". |

| Amnesty International Indonesia | "amnestyindonesia.org". |

| Amnesty International Ireland | "amnesty.ie". |

| Amnesty International Israel | "amnesty.org.il". |

| Amnesty International Italy | "amnesty.it". |

| Amnesty International Japan | "amnesty.or.jp". |

| Amnesty International Jersey | "amnesty.org.je". |

| Amnesty International Luxembourg | "amnesty.lu". |

| Amnesty International Malaysia | "amnesty.my". |

| Amnesty International Mauritius | "amnestymauritius.org". |

| Amnesty International Mexico | "amnistia.org.mx". |

| Amnesty International Moldova | "amnesty.md". |

| Amnesty International Mongolia | "amnesty.mn". |

| Amnesty International Morocco | "amnesty.ma". |

| Amnesty International Nepal | "amnestynepal.org". |

| Amnesty International Netherlands | "amnesty.nl". |

| Amnesty International New Zealand | "amnesty.org.nz". |

| Amnesty International Norway | "amnesty.no". |

| Amnesty International Paraguay | "amnistia.org.py". |

| Amnesty International Peru | "amnistia.org.pe". |

| Amnesty International Philippines | "amnesty.org.ph". |

| Amnesty International Poland | "amnesty.org.pl". |

| Amnesty International Portugal | "amnistia.pt". |

| Amnesty International Puerto Rico | "amnistiapr.org". |

| Amnesty International Russia | "amnesty.org.ru". |

| Amnesty International Senegal | "amnesty.sn". |

| Amnesty International Slovak Republic | "amnesty.sk". |

| Amnesty International Slovenia | "amnesty.si". |

| Amnesty International South Africa | "amnesty.org.za". |

| Amnesty International South Korea | "amnesty.or.kr". |

| Amnesty International Spain | "es.amnesty.org". |

| Amnesty International Sweden | "amnesty.se". |

| Amnesty International Switzerland | "amnesty.ch". |

| Amnesty International Taiwan | "amnesty.tw". |

| Amnesty International Thailand | "amnesty.or.th". |

| Amnesty International Togo | "amnesty.tg". |

| Amnesty International Tunisia | "amnesty-tunisie.org". |

| Amnesty International Turkey | "amnesty.org.tr". |

| Amnesty International UK | "amnesty.org.uk". |

| Amnesty International Ukraine | "amnesty.org.ua". |

| Amnesty International Uruguay | "amnistia.org.uy". |

| Amnesty International USA | "amnestyusa.org". |

| Amnesty International Venezuela | "amnistia.me". Archived from the original on 1 June 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2013. |

Charitable status

In

the UK Amnesty International has two principal arms, Amnesty

International UK and Amnesty International Charity Ltd. Both are

UK-based organizations but only the latter is a charity.

Principles

The core principle of Amnesty International is a focus on prisoners of conscience,

those persons imprisoned or prevented from expressing an opinion by

means of violence. Along with this commitment to opposing repression of

freedom of expression, Amnesty International's founding principles

included non-intervention on political questions, a robust commitment to

gathering facts about the various cases and promoting human rights.

One key issue in the principles is in regards to those

individuals who may advocate or tacitly support resorting to violence in

struggles against repression. AI does not judge whether recourse to

violence is justified or not. However, AI does not oppose the political

use of violence in itself since The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

in its preamble, foresees situations in which people could "be

compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against

tyranny and oppression". If a prisoner is serving a sentence imposed,

after a fair trial, for activities involving violence, AI will not ask

the government to release the prisoner.

AI neither supports nor condemns the resort to violence by

political opposition groups in itself, just as AI neither supports nor

condemns a government policy of using military force in fighting against

armed opposition movements. However, AI supports minimum humane

standards that should be respected by governments and armed opposition

groups alike. When an opposition group tortures or kills its captives,

takes hostages, or commits deliberate and arbitrary killings, AI

condemns these abuses.

Amnesty International opposes capital punishment in all cases,

regardless of the crime committed, the circumstances surrounding the

individual or the method of execution.

Objectives

Amnesty International's vision is of a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. In pursuit of this vision, Amnesty International's mission is to undertake research and action focused on preventing and ending grave abuses of the rights to physical and mental integrity, freedom of conscience and expression, and freedom from discrimination, within the context of its work to promote all human rights. -Statute of Amnesty International, 27th International Council meeting, 2005

Amnesty International primarily targets governments, but also reports on non-governmental bodies and private individuals ("non-state actors").

There are six key areas which Amnesty deals with:

- Women's, children's, minorities' and indigenous rights

- Ending torture

- Abolition of the death penalty

- Rights of refugees

- Rights of prisoners of conscience

- Protection of human dignity.

Some specific aims are to: abolish the death penalty, end extra judicial executions and "disappearances", ensure prison conditions meet international human rights standards, ensure prompt and fair trial for all political prisoners, ensure free education to all children worldwide, decriminalize abortion, fight impunity from systems of justice, end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, free all prisoners of conscience, promote economic, social and cultural rights for marginalized communities, protect human rights defenders, promote religious tolerance, protect LGBT rights, stop torture and ill-treatment, stop unlawful killings in armed conflict, uphold the rights of refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers, and protect human dignity.

Amnesty International at the 2009 Marcha Gay in Mexico City, 20 June 2009

Additionally, Amnesty International has developed ways to publicize

information and mobilize public opinion. The organization considers the

publication of impartial and accurate reports as one of its strengths.

Reports are researched by: interviewing victims and officials, observing

trials, working with local human rights activists, and monitoring the

media. It aims to issue timely press releases and publishes information

in newsletters and on web sites. It also sends official missions to

countries to make courteous but insistent inquiries.

Campaigns to mobilize public opinion can take the form of

individual, country, or thematic campaigns. Many techniques are

deployed, such as direct appeals (for example, letter writing), media

and publicity work, and public demonstrations. Often, fund-raising is

integrated with campaigning.

In situations which require immediate attention, Amnesty

International calls on existing urgent action networks or crisis

response networks; for all other matters, it calls on its membership. It

considers the large size of its human resources to be another of its

key strengths.

The role of Amnesty International has a significant impact on

getting citizens onboard with focusing on human rights issues. These

groups influence countries and governments to give their people justice

with pressure and in human resources. An example of Amnesty

International's work is writing letters to free imprisoned people that

were put there for non-violent expressions. The group now has power,

attends sessions, and became a source of information for the UN. The

increase in participation of non-governmental organizations changes how

we live today. Felix Dodds states in a recent document: "In 1972 there were 39 democratic countries in the world; by 2002, there were 139." This shows that non-governmental organizations make enormous leaps within a short period of time for human rights.

Country focus

Protesting Israel's policy against African refugees, Tel Aviv, 9 December 2011

Amnesty reports disproportionately on relatively more democratic and open countries,

arguing that its intention is not to produce a range of reports which

statistically represents the world's human rights abuses, but rather to

apply the pressure of public opinion to encourage improvements.

The demonstration effect

of the behaviour of both key Western governments and major non-Western

states is an important factor: as one former Amnesty Secretary-General

pointed out, "for many countries and a large number of people, the

United States is a model," and according to one Amnesty manager, "large

countries influence small countries." In addition, with the end of the Cold War,

Amnesty felt that a greater emphasis on human rights in the North was

needed to improve its credibility with its Southern critics by

demonstrating its willingness to report on human rights issues in a

truly global manner.

According to one academic study, as a result of these

considerations the frequency of Amnesty's reports is influenced by a

number of factors, besides the frequency and severity of human rights

abuses. For example, Amnesty reports significantly more (than predicted

by human rights abuses) on more economically powerful states; and on

countries which receive US military aid, on the basis that this Western

complicity in abuses increases the likelihood of public pressure being

able to make a difference.

In addition, around 1993–94, Amnesty consciously developed its media

relations, producing fewer background reports and more press releases,

to increase the impact of its reports. Press releases are partly driven

by news coverage, to use existing news coverage as leverage to discuss

Amnesty's human rights concerns. This increases Amnesty's focus on the

countries the media is more interested in.

In 2012, Kristyan Benedict,

Amnesty UK's campaign manager whose main focus is Syria, listed several

countries as "regimes who abuse peoples' basic universal rights": Burma, Iran, Israel, North Korea and Sudan.

Benedict was criticized for including Israel in this short list on the

basis that his opinion was garnered solely from "his own visits", with

no other objective sources.

Amnesty's country focus is similar to that of some other comparable NGOs, notably Human Rights Watch:

between 1991 and 2000, Amnesty and HRW shared eight of ten countries in

their "top ten" (by Amnesty press releases; 7 for Amnesty reports). In addition, six of the 10 countries most reported on by Human Rights Watch in the 1990s also made The Economist's and Newsweek's "most covered" lists during that time.

Funding

Amnesty

International is financed largely by fees and donations from its

worldwide membership. It says that it does not accept donations from

governments or governmental organizations. According to the AI website,

"these personal and unaffiliated donations allow AI to maintain full independence from any and all governments, political ideologies, economic interests or religions. We neither seek nor accept any funds for human rights research from governments or political parties and we accept support only from businesses that have been carefully vetted. By way of ethical fundraising leading to donations from individuals, we are able to stand firm and unwavering in our defence of universal and indivisible human rights."

However, AI has received grants over the past ten years from the UK Department for International Development, the European Commission, the United States State Department and other governments.

AI (USA) has received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, but these funds are only used "in support of its human rights education work."

Criticism and controversies

Criticism of Amnesty International includes claims of excessive pay

for management, underprotection of overseas staff, associating with

organizations with a dubious record on human rights protection, selection bias, ideological and foreign policy bias against either non-Western countries or Western-supported countries, or even bias for terrorist groups, as well as criticism of Amnesty's policies relating to abortion. A recent report also shows an internal toxic work environment.

Governments and their supporters have criticized Amnesty's criticism of their policies, including those of Australia, Czech Republic, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Iran, Israel, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, Russia, Nigeria, and the United States,

for what they assert is one-sided reporting or a failure to treat

threats to security as a mitigating factor. The actions of these

governments, and of other governments critical of Amnesty International,

have been the subject of human rights concerns voiced by Amnesty.

The Sudan Vision Daily, a daily newspaper in Sudan, compared Amnesty to the US National Endowment for Democracy, and claimed "it is, in essence, a British intelligence organization which is a part of the Government decision making system."

CAGE controversy

Amnesty International suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticized Amnesty in February 2010 for its high-profile associations with Moazzam Begg, the director of Cageprisoners, representing men in extrajudicial detention.

"To be appearing on platforms with Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban, Begg, whom we treat as a human rights defender, is a gross error of judgment," she said. Sahgal argued that by associating with Begg and Cageprisoners, Amnesty was risking its reputation on human rights.

"As a former Guantanamo detainee, it was legitimate to hear his

experiences, but as a supporter of the Taliban it was absolutely wrong

to legitimise him as a partner," Sahgal said. She said she repeatedly brought the matter up with Amnesty for two years, to no avail. A few hours after the article was published, Saghal was suspended from her position.

Amnesty's Senior Director of Law and Policy, Widney Brown, later said

Sahgal raised concerns about Begg and Cageprisoners to her personally

for the first time a few days before sharing them with the Sunday Times.

Sahgal issued a statement saying she felt that Amnesty was

risking its reputation by associating with and thereby politically

legitimizing Begg, because Cageprisoners "actively promotes Islamic

Right ideas and individuals".

She said the issue was not about Begg's "freedom of opinion, nor about

his right to propound his views: he already exercises these rights fully

as he should. The issue is ... the importance of the human rights

movement maintaining an objective distance from groups and ideas that

are committed to systematic discrimination and fundamentally undermine

the universality of human rights." The controversy prompted responses by politicians, the writer Salman Rushdie, and journalist Christopher Hitchens, among others who criticized Amnesty's association with Begg.

After her suspension and the controversy, Saghal was interviewed

by numerous media and attracted international supporters. She was

interviewed on the US National Public Radio

(NPR) on 27 February 2010, where she discussed the activities of

Cageprisoners and why she deemed it inappropriate for Amnesty to

associate with Begg. She said that Cageprisoners' Asim Qureshi spoke supporting global jihad at a Hizb ut-Tahrir rally. She stated that a bestseller at Begg's bookshop was a book by Abdullah Azzam, a mentor of Osama bin Laden and a founder of the terrorist organization Lashkar-e-Taiba.

In a separate interview for the Indian Daily News & Analysis, Saghal said that, as Quereshi affirmed Begg's support for global jihad on a BBC World Service programme, "these things could have been stated in his [Begg's] introduction" with Amnesty. She said that Begg's bookshop had published The Army of Madinah, which she characterized as a jihad manual by Dhiren Barot.

Pay controversy

In February 2011, newspaper stories in the UK revealed that Irene Khan

had received a payment of £533,103 from Amnesty International following

her resignation from the organization on 31 December 2009,

a fact pointed to from Amnesty's records for the 2009–2010 financial

year. The sum paid to her was more than four times her annual salary

(£132,490). The deputy secretary general, Kate Gilmore, who also resigned in December 2009, received an ex-gratia payment of £320,000.

Peter Pack, the chairman of Amnesty's International Executive Committee

(IEC), initially stated on 19 February 2011: "The payments to outgoing

secretary general Irene Khan shown in the accounts of AI (Amnesty

International) Ltd for the year ending 31 March 2010 include payments

made as part of a confidential agreement between AI Ltd and Irene Khan" and that "It is a term of this agreement that no further comment on it will be made by either party."

The payment and AI's initial response to its leakage to the press led to considerable outcry. Philip Davies, the Conservative MP for Shipley, criticized the payments, telling the Daily Express:

"I am sure people making donations to Amnesty, in the belief they are

alleviating poverty, never dreamed they were subsidising a fat cat

payout. This will disillusion many benefactors."

On 21 February 2011, Peter Pack issued a further statement, in which he

said that the payment was a "unique situation" that was "in the best

interest of Amnesty's work" and that there would be no repetition of it.

He stated that "the new secretary general, with the full support of the

IEC, has initiated a process to review our employment policies and

procedures to ensure that such a situation does not happen again."

Pack also stated that Amnesty was "fully committed to applying all the

resources that we receive from our millions of supporters to the fight

for human rights".

On 25 February 2011, Pack sent a letter to Amnesty members and

staff. In 2008, it stated, the IEC decided not to prolong Khan's

contract for a third term. In the following months, IEC discovered that

due to British employment law, it had to choose between three options:

offering Khan a third term; discontinuing her post and, in their

judgement, risking legal consequences; or signing a confidential

agreement and issuing a pay compensation.

2019 Report on workplace bullying within Amnesty International

In February 2019, Amnesty International's management team offered to

resign after an independent report found what it called a "toxic

culture" of workplace bullying. Evidence of bullying, harassment, sexism and racism

was uncovered after two 2018 suicides were investigated: that of

30-year Amnesty veteran Gaetan Mootoo in Paris in May 2018 (who left a note citing work pressures); and that of 28-year-old intern Rosalind McGregor in Geneva in July 2018.

Kurdish Hunger Strike occupation

In April 2019, 30 Kurdish activists, some of whom are on an indefinite hunger strike, occupied Amnesty International's building in London in a peaceful protest, in order to speak out against Amnesty's silence on the isolation of Abdullah Öcalan in a Turkish prison.

The hunger strikers have also spoken out about "delaying tactics" by

Amnesty, and being denied access to toilets during the occupation,

despite this being a human right. Two of the hunger strikers, Nahide Zengin and Mehmet Sait Zengin, received paramedic treatment and were taken to hospital during the occupation. Late in the evening of 26 April 2019, the London Met police arrested 21 remaining occupiers.

Awards and honours

In

1977, Amnesty International was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for

"having contributed to securing the ground for freedom, for justice, and

thereby also for peace in the world".

In 1984, Amnesty International received the Four Freedoms award in the category of Freedom of Speech.

In 1991, Amnesty International was awarded the journalistic prize Golden Doves for Peace by the "Archivio Disarmo" Research Center in Italy.

Cultural impact

Human rights concerts

Opening stages of the 19 September 1988 show at Philadelphia's JFK Stadium.

A Conspiracy of Hope was a short tour of six benefit concerts

on behalf of Amnesty International that took place in the United States

during June 1986. The purpose of the tour was not to raise funds but

rather to increase awareness of human rights and of Amnesty's work on

its 25th anniversary. The shows were headlined by U2, Sting and Bryan Adams and also featured Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Joan Baez, and The Neville Brothers. The last three shows featured a reunion of The Police.

At a press conferences in each city, at related media events, and

through their music at the concerts themselves, the artists engaged with

the public on themes of human rights and human dignity. The six

concerts were the first of what subsequently became known collectively

as the Human Rights Concerts – a series of music events and tours staged

by Amnesty International USA between 1986–1998.

Human Rights Now! was a worldwide tour of twenty benefit concerts

on behalf of Amnesty International that took place over six weeks in

1988. Held not to raise funds but to increase awareness of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on its 40th anniversary and the work of Amnesty International, the shows featured Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, and Youssou N'Dour, plus guest artists from each of the countries where concerts were held.

Artists for Amnesty

Amnesty International, through its "Artists for Amnesty" programme

has also endorsed various cultural media works for what its leadership

often consider accurate or educational treatments of real-world topics

that fall within the range of Amnesty's concern:

- A is for Auschwitz

- At the Death House Door

- Blood Diamond

- Bordertown

- Catch a Fire

- In Prison My Whole Life

- Invictus

- Lord of War

- Rendition

- The Constant Gardener

- Tibet: Beyond Fear

- Trouble the Water

- 12 Years a Slave

- Django Unchained

- The Help